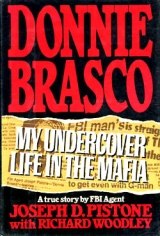

Текст книги "Donnie Brasco: My Undercover Life in the Mafia"

Автор книги: Joseph D. Pistone

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 24 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

18

THE HITS

There was no quick resolution to the sitdowns. I just had to stay cool and wait, for days, weeks.

Lefty came down to Holiday, and Rossi and I were driving him to Miami, where he needed to talk to some people.

“I wanna get rid of all the old men,” he says. “They can’t do us no good. They’re eighty years old. They don’t wanna be bothered. Sonny tells me to call them to come to fucking wakes. Leave these people alone. You can’t retire them. It’s no good. Because they lose their prestige. We’re stuck with them.”

Lefty had been made an acting captain by Sonny, and he was sizing things up in the family. I tried to pump him a little on personnel. “Jerry Chilli’s on the side with Caesar and them, right?”

“Both brothers are on the other side,” he says, meaning both Joe and Jerry Chilli.

“Who’s his skipper, who’s he with?”

“He’s with Sonny Red’s man, Trinny,” he says, indicating rival captains Alphonse “Sonny Red” Indelicato and Dominick “Big Trin” Trinchera. “One’s kicking back to Trinny a G-note a week. The other one is kicking back three grand. That’s why they got power, them two guys. Those brothers are making a ton of money. We ain’t making it because we gotta walk the chalk line. This is what we’re told.”

“Joey Massino still got the coffee trucks?”

“Yeah. Joe Massino’s got good men. They all love me. We grew up together and hung out together. He knows where the strength is.”

“Joey goes to visit Rusty, huh?”

“Oh, yeah, he’s gotta go see him. He doesn’t know what’s going on with Mirra. He can’t butt in. When Joe Massino goes up there in a couple of weeks, he’ll tell him.”

“Well, Sonny’s gonna do the right thing. I don’t think anybody’s gonna fuck over Sonny.”

He ranted for a while about Mirra.

I say, “Well, he’s not gonna go against you one on one, you know that.”

“Ain’t a fucking man in New York City would go up against me one on one, because I would do it cowboy-style, right on South Street, one block walking at each other. How many pistols you want? Two? Let’s walk up against each other. One of us got to fucking die, or both of us die. That’s what I would do. I wouldn’t give a fuck, and don’t forget it. I’ll stay with Sonny and show honor.”

“Well, Rusty knows that.”

“Hey, let me tell you something. We were fighting a war, the Bonnanos. Rusty’s my chauffeur. Because you know what kind of a fucking man I was, and he was the fucking underboss. And he had to listen to me while he was driving the car: ‘Rusty, cut over here ... leave my fucking window open.’ He was a good wheelman.”

But Rusty was a tough boss, Lefty went on. During a war Rusty was in Canada, and he called Lefty and ordered him to come up. He didn’t even tell Lefty where he was, just where to go.

“I had four small kids. ‘Go pack a grip,’ he says. So I go pack a grip. Get on the fucking plane. Two pistols. Go to Canada, order a room. He says, ‘I’m gonna meet three guys on that corner. Don’t take your eyes off them. If anything happens to me, go all the way. Cops on the corner, blow them away.’

“Six fucking weeks he’s got me out there. You’re not allowed to make a phone call to your family. Good thing I had an ex-wife then who understood, never asked questions what happened to me or anything like that. Six fucking weeks. Now, I taught my new wife, Louise; ‘Look, anything happens, you don’t see me come in, don’t you yell for anybody—he just didn’t come home, you don’t know nothing.’ I says, ‘You wanna cry, it’s your fucking business. Don’t ask anybody on the corner where I’m at or question my sister. Just say, ’He didn’t come home—this is what my husband told me to say and these are his orders, and that’s it.‘ ”

“Rusty knows what we got down here, right?”

“Oh, yeah. He knows everything. That’s the trouble. They all know it.”

“Donnie, listen to me carefully,” Lefty says. It was Saturday night, April 11, and I had placed my regular call. “The car. Your friend’s car. Meet me in Fort Lauderdale tomorrow.”

“Why, what’s the matter?”

“Why don’t you just listen? Because I can cancel you out right now. I want you to come in alone. I don’t know what name I’m going under. I’m gonna come in with some people. Could you get that car?”

That was Rossi’s four-door Lincoln. “I guess so, why?”

“Donnie, don’t say, ‘I guess so, why?’ Just say yes and you meet me in Lauderdale.”

“Of course I can get it.”

“I could use Spaghetti. But my friend and I want you. I’m trying to get in touch with Nick, because we cannot go in cold. I gotta go into that hotel for one day, and then we’ll take it from there. Okay?”

“All right.” Nick was the manager at the Deauville Hotel, Lefty’s friend.

“That’s all, pal. I’ll explain everything. My friend requested you. You’re coming in with us. I got work to do. If you don’t like the idea, if you back out, fine, no problem. You go on back home. But I want to put you in on this, serious. Because we spoke about something, you and I, right?”

“I know what you’re talking about.”

“I got plane tickets, ten o‘clock. Delta flight 1051, first-class, from Kennedy. We’ll be there twelve-thirty tomorrow afternoon. You start coming in six hours before time. Drive in from Tampa with your big car. You pick us up at the airport. Don’t get there two hours before time. I don’t want you seen there. You time yourself, stay away from the airport until time, you follow me?”

“Yeah.”

“We just get in the car and we’re gone. Now, you satisfied? Because I tell you, if you wanna back away from it, no problem, you go back and there’s nothing said. I told you, two guys requested you, him and I. I’m taking full responsibility. He asked me if I wanted you. Okay?”

“All right.”

Years earlier, Lefty had promised that when the time was right, he’d take me along. Now I was being taken on a hit.

From various conversations over the last couple of weeks I had pieced together just how the feuding Bonanno family factions lined up, just how ominous the friction was between them. Aligned with Rusty Rastelli were Sally Farrugia, consiglieri Steve Cannone, captains Sonny Black and Joe Massino. Against Rusty were captains Caesar Bonventre, Philip “Philly Lucky” Giaccone, Dominick “Big Trin” Trinchera, and Alphonse “Sonny Red” Indelicato and his son, Anthony Bruno Indelicato.

Sonny, as usual, had been discreet about everything. And especially since the sitdowns about me were still going on, he wasn’t telling me anything. As close as we were, he was putting the family first, going by the rules. I probably would have been told more if I had been in New York. But everybody was being careful on the telephone. Lefty had been hinting at how everything was coming to a head, and had let me know that Sonny was the key to all the power, especially now that he had an alliance with Santo Trafficante. The opposing captains feared Sonny’s expanding power.

I faced two major problems. One was that as an agent, I couldn’t actually participate in a hit—in fact, it was our duty to prevent the hit if possible—yet as a badguy I couldn’t turn down the invitation without losing credibility.

The other problem was that I wasn’t at my apartment in Holiday, Florida. I wasn’t anywhere near Florida. I was home. I hadn’t been home for over a month. Over the years I had missed most of my children’s important days. On this weekend my youngest daughter was being confirmed. Everything was quiet on the job for the moment, so I snuck home for the weekend. This was Saturday night. The confirmation was tomorrow, Sunday. So was the hit in Florida.

First things first. I had to go on the hit. Technically, since I wasn’t a made guy, I could refuse and it wouldn’t be held against me. Realistically, though, it would undercut the credibility I had been working to establish since 1976. If I didn’t go, they would carry out the hit, anyway. I didn’t know who the target was. I figured it was one of the wiseguys in the opposition faction, probably one of the four captains, but I didn’t know who, so there was nobody the FBI could warn. And I didn’t know where or when. They might go right out on the hit, or they might hang around and case the situation, wait for a good opportunity. At least if I was along, maybe I could find out who the target was enough ahead of time so I could tip off our guys so they could snatch him off the street.

I called Case Agent Jim Kinne in Tampa. He agreed that the only thing we could do is put a surveillance team on me from the time I got to Miami. When I hook up with Lefty and his crew, if I can find out soon enough who they’re going to hit, maybe I can get to a phone. Or if I can’t find out right away, the surveillance team can tail us until the last possible minute, until I signal or something, and they can stop us on a traffic violation or some bullshit charge. They could say they recognize us as mob guys, ask us what we’re all doing down there together—apply a routine hassling that happens to these guys all the time. That way they probably wouldn’t suspect a tip-off, yet it might be enough of a disruption to cause them to call off the hit.

Kinne would hurry to set up the surveillance. I would catch the first flight to Miami. It was a very dicey situation. The surveillance team could get spotted or lose us. Everybody with Lefty would be given a gun, and I could be designated the triggerman. What if the surveillance team is out of it and we’re headed for the hit and I’m the hitter—what the hell will I do? I didn’t know of any precedents for this situation.

But long before, when I had imagined the possibility of this kind of situation, I had made a personal decision to cover it: Whatever the rules, if the target is a badguy and it’s him or me, he goes.

I called Rossi and laid out the situation. I would fly into Miami. He would drive the big car to Miami for me, then he would fly back to Tampa.

Now I had to tell my family that I would miss my daughter’s confirmation. We were going to have a houseful of relatives and friends. Relatives were flying in from all over. Not even my wife knew how deeply I was involved now in the turmoil within the Bonanno family.

First I told my wife. I said I got a phone call and I had to return to Florida immediately. I wasn’t going to give her details, because I didn’t want her to worry any more than she already did. But she had overheard me talking to Agent Kinne, and so she knew that the mob wanted me to kill somebody.

I told her that it was a very important thing I was involved in and that I had to go because somebody’s life might be at stake, and we were required to prevent a killing if we could. A lot of people were depending on me for this operation—it was the old story. Beyond that, all I could tell her was not to worry. I was never very good at talking about a thing like that at a time like that.

She was furious and scared. She yelled at me and cried. She hated the Bureau. How could I be put in this position? Who was going to be there to protect me? Why did I have to go, why not somebody else? Why not somebody who didn’t have a wife and children? She was shaking.

This was the lowest point since her accident.

My youngest daughter was now fourteen. I sat down with her and told her I couldn’t be at her confirmation because something had come up with my job and I had an obligation to do it and there was nothing I could do about it. She cried and said, “Daddy, I don’t want you to go because this is a special day for me.”

But then she said she was mad that I would leave her on a special day but that at least she had her grandfather there to stand in for her.

I had to leave for the airport right away. I really had no choice.

I flew to Miami and picked up the car from Rossi. I drove to the Fort Lauderdale Airport, arriving five minutes before the scheduled arrival of Lefty’s flight. Lefty’s flight came, people filed off. No Lefty, no nobody.

I called Sonny in Brooklyn. “What’s going on, Sonny? Nobody’s here.”

“We called it off.”

“What do you mean, called it off?”

“Look, call the other guy, he’ll explain it to you.”

“Where’s he?”

“He’s home, Donnie.”

I drove back to my apartment in Holiday. I needed the six hours to burn off my rage. My daughter’s confirmation had gone on without me, and the hit hadn’t gone on at all.

Then I called Lefty. He told me that he had gone to the airport and called back to Sonny as he was supposed to, and Sonny said it was canceled. “It was too late to call you,” he says, “because you were already on the way from Tampa.”

The hit was going to be on Philly Lucky. They called it off because he was down there by himself, and they decided they wanted to get three captains together, that it wasn’t smart to hit them one at a time.

“I’m sorry, pal,” Lefty says.

“That’s all right. What the hell, you couldn’t get in touch with me. Things like that happen.”

“I know. That’s it.”

“Well, if it would have went, it would have been good, right?”

“I can’t talk about it.”

“I’m just saying—”

“No, I can’t talk about that. If they’d have left it up to me, you know ...”

“Next time, Left, don’t ask me or say, ‘You don’t have to do it.’ We got something to do, I do it. Don’t ever feel that I’m gonna back out of something.”

“You had a choice, though.”

“What choice? We do things together. I’m not worried about no choice.”

Anthony “Mr. Fish” Rabito was a fat wiseguy, maybe 5’9”, 250 pounds, with a fleshy face, who once ran seafood restaurants. He was a bachelor and had an apartment at 411 East Fifty-Third Street in Manhattan. His apartment was popular with other wiseguys, who often used it as a place to take their girlfriends for an hour or so. He was a friend of Sonny’s. Sonny said that Rabito was a good guy to contact and stay with when you have to work the streets during, say, a war.

On April 13, two days after the aborted hit, Lefty called.

“Donnie, listen to me carefully and listen good. I’m leaving with some people. I can’t make no phone calls. If everything comes all right, you’ll be in pretty good shape in New York. Understand?”

“Yeah, all right.”

“You don’t know all right.”

“I’m just saying all right that you—”

“Because it might take two weeks. It might take a while. Now, this is the last time you’re gonna hear from me. I’m being picked up in a little while. And don’t call the other guy.”

“Okay. Don’t call nobody.”

The only person he wanted me to call was Louise. He wanted me to call her twice a day in case she had any problems; at six P.M. when she got home from work, and at eleven P.M., before she went to bed, and to send her $1,000 for bills.

“And do me a favor, try to stay as close as possible just in case when something does come off, that we know where to contact you. In other words, like, I’ll use the club. You understand?”

“Yeah.”

“Because I’m gonna work from the street.”

I alerted Case Agent Jerry Loar in New York. A surveillance team saw Lefty and Louise leave their apartment, get in his car, and drive to Rabito’s building. Lefty got out carrying a brown paper bag and went to Rabito’s apartment. Louise drove away.

I didn’t hear from Lefty until five days later, when I finally learned that I had survived the sitdowns.

“I just got back from Brooklyn,” he says. “Everything went good. We’ll be all right. We’re on top.”

“Hey, that’s good.”

“But these motherfuckers, they was all partying. They thought I was clipped, you know? When I was missing? They had me fucking dead, these motherfuckers. So everybody’s celebrating.”

“Are they crazy or what?”

“Even Mike Sabella. He doesn’t know that I know. But he was saying, ‘That’s a shame, but I’m glad I took his wife’s jewelry.’ ”

Lefty had put up his wife’s jewelry as collateral on a loan.

I say, “What a surprise he’s gonna have, huh?”

“Unbelievable, these motherfuckers. Wait’ll I talk to Blackstein tomorrow. He knew they thought I was clipped, but he didn’t know it got that far.”

Blackstein was Sonny Black.

“Those cocksuckers,” Lefty says, “they don’t know the surprise they’re gonna get in a couple months. I got news for you, pal. Nobody bothers you no more. When that man comes out, you’ll be in good shape.”

“Oh, yeah?”

“I stuck with you all the way. And it’s very surprising, he stood by you too.”

“Blackstein?”

“Yeah.”

“Good.”

“Because what I did this here week, you’re a lot better off tonight.”

“Than last week, huh?”

“Ain’t no way of stopping the situation. I can’t go into details. When you walk around, you can smack anybody you want in the mouth, that’s all I can tell you.”

“Anybody?”

“Anybody. When I get out there, you point them out to me, you smack them in the fucking mouth. Donnie, you’re gonna be very shocked. Blackstein is so fucking happy.”

He wanted me to meet him in Miami, where he would fill me in more on the results of the sitdowns.

“Do me a favor,” he says. “Tell Tony bring a tie and a shirt. Not dress like a fucking Hoosier from Pennsylvania. I’m bringing down sharp clothes.”

He put Louise on the phone. “Hi, Donnie, what you gonna do tomorrow?”

“Same thing I do every Sunday.”

“No special plans? What kind of dinner you going to eat?”

“I don’t know.”

“It’s Easter.”

“I know, but I don’t have any special buddy to spend Easter with anymore, you know?”

“Oh, we gotta fix that.”

I started thinking about close calls and what would happen if Lefty or Sonny started adding things up. There was the time in P. J. Clarke’s when I was with Larry Keaton and Larry was recognized as an agent and Lefty was told. And when were they going to get the call from the Chicago mob tipping them off to the fact that Tony Conte was an agent? Going way back, what about the guy at Jilly’s in Brooklyn that I had once arrested? Would he see me again on the street and remember who I was? And there was the ABSCAM boat, and there was Rocky.

In the mob it’s your close friend that will kill you. Here I was staying with Lefty all the time in hotels, with him twenty-four hours a day where any little slip could be noticed. I was dodging a lot of bullets, so to speak.

Rossi and I picked up Lefty at the airport in Miami. Mirra and his side had lost the sitdowns; I was okay.

“The case is closed,” Lefty says. “There’s no more. They lost, and they lost nationwide. New York, Miami, Chicago—they lost nationwide. Listen, that’s why it took me fucking five days to go out and do what I had to do.”

“That’s good. Sonny happy now?”

“Forget about it, lit up like Luna Park. Well, I’m glad youse are satisfied, because this is the whole thing in a nutshell.”

“Hey, Left, that’s what we were working for all this time, right?”

“We’re hurting, in the sense we don’t have big money. But we have the power today. I’d rather have the power than the money. Because these guys have all got the money, and they don’t know what to do with it no more. Where they gonna go? They can’t run to nobody. They still got their captains. But who the captains gonna go to?”

“Are they still gonna be under Rusty, those guys?”

“Everybody’s under Rusty. The law of the land. Nationwide. There’s only one fucking boss.”

“And that’s it?”

“And nobody can take his place.”

We went into the piano bar at the Deauville. Lefty told us that he, Sonny, Joey Massino, and Nicky Santora had been engaged in an important job in New York “for the Commission.” He said that they had “put it together” and that in return they had been assured by the Commission that Rastelli would remain boss.

I didn’t know what Lefty had done during his five days “working from the street” or what they had done for the Commission, or whether it was all one and the same. The FBI had kept him under surveillance for two or three days and nothing happened, so they abandoned it—they don’t have unlimited manpower to keep everybody under surveillance for long periods. I assumed it involved a hit, because everything was typical of that—the secrecy and the working from the street, the fact that afterward all the serious problems raised in the sitdowns and going all the way up to the boss were solved. And finally the whole thing had been ratified nationwide by the Mafia Commission representing all the families. I figured that the paper bag Lefty had taken to Rabito’s contained guns—that was a common way of carrying a bunch of them.

I couldn’t ask direct questions. Supposedly I was experienced enough now as a connected guy to figure out certain things on my own, take what I was told, and, as Lefty liked to say, “leave it alone.”

Even though everything pointed to a hit, I couldn’t think of anybody that was missing. No bodies turned up.

We were sitting there listening to Lefty spin out his tale of trouble between family factions, shit with Mirra, all the difficult and violent solutions within the mob.

“Lefty,” Rossi says, “I understand how we all like to make money. But what is the actual advantage to being a wiseguy?”

“Are you kidding? What the ... Donnie, don’t you tell this guy nothing? Tony, as a wiseguy you can lie, you can cheat, you can steal, you can kill people—legitimately. You can do any goddamn thing you want, and nobody can say anything about it. Who wouldn’t want to be a wiseguy?”

A few guys from the New York crew were down having a good time. Rossi wanted to use the pay phone and didn’t have any change. He asked one of the guys—the retired New York detective—if he had change for a dollar.

“Use these,” the ex-cop says, handing Rossi four copper-colored metal discs the size of quarters. “They work good.” He said that a few of the guys in New York had access to large supplies of these slugs at five hundred for fifty bucks—ten cents apiece.

Rossi used one in the phone and later turned in the other three to the contact agent.

The next afternoon we were sitting by the pool at the Deauville. Lefty was moaning and groaning about us not hustling enough. He wanted a lounge on the beach, for status. “Let’s do it now,” he says, “because I’m older and tired.” He complained about everything. “Promised about the racetrack. We embarrassed ourselves, it died. Promised about the Vegas Night, it died. Promised about bingo, it died.”

Rossi went inside. Lefty complained that Rossi wasn’t pulling his weight and that I wasn’t leaning on Rossi enough. He droned on for another hour. At about four o‘clock he says, “I think I’ll go up and take a nap so I’ll be fresh for when we go out tonight.”

A few minutes later Rossi came out. “You won’t believe what I did. I turned the air-conditioning up full-blast and took the switch off.”

“Holy shit,” I say. “We’re gonna hear him screaming all the way out here at the pool. I ain’t going up there for a while because he’s gonna be going bullshit.”

Lefty hated air-conditioning. Summers in New York or Tampa, in cars, in hotel rooms, he would not allow me to turn it on. He couldn’t stand the cold air blowing on him. We’d be riding around on the hottest days with the car windows open. We had fights. I’d turn the air-conditioning on, he’d turn it off. I’d be drenched in sweat, he didn’t sweat at all. “How can you not sweat in this car?” I’d say. “Ah, just keep the windows open and you don’t need air-conditioning,” he’d answer.

We always stayed together in hotel rooms. He always had a cold. Sometimes, even in the summer, he would turn the heat on in the room. “It’s too damp in here,” he’d say. “Lefty, you’re fucking nuts. This is crazy. I’m getting another room.” He chain-smoked his English Ovals. If I was lucky, he had a room where you could open the windows.

This time we were staying in one of the penthouse suites, the three of us together. Finally Rossi and I went up to the room.

“Donnie, you cocksucker! You did this!” Lefty is stomping around the nice cool room.

“What are you talking about?”

“You turned this fucking air-conditioning up, and it can’t turn down!”

“Left, I haven’t been in the room since we left it this afternoon.”

“You fucking snuck up here and did this just to break my fucking balls! Call the maintenance, get this fucking air-conditioning fixed!”

“Why don’t you just turn it down?”

“It ain’t got no fucking switch!”

Rossi is laughing so hard, he can barely stand up, because Lefty is hollering at me and not him.

“I couldn’t even take a nap,” Lefty rants on. “I been up here two fucking hours freezing my ass off!”

“Why didn’t you call maintenance?”

“Because you did this thing!”

“Okay, I did it.”

“You ain’t going to dinner with me tonight!”

“Okay, I’ll eat by myself.”

Meanwhile Rossi is on his hands and knees. “Here it is,” he says, pulling the switch out from under the couch. He puts the switch back on and turns the air-conditioning off.

The room is filled with too much cigarette smoke and too much Lefty, and it’s making me crazy. I walk out. Rossi comes after me. I stop in the hall. “Tony, I’m going back in there and stab that motherfucker.”

“Hey, Don—”

“I can’t take him anymore. I’m gonna stab him. We’ll just go down to the pool, let them find him up here. Who’s gonna give a fuck if they find another dead wiseguy?”

“Hey, Donnie, take it easy.”

With everything else there was to worry about, I had to take this daily shit. Rossi thought I was serious. That’s how fed up I was with Lefty.

I talked to Lefty in the morning on May 5. It was a routine phone call. Nothing in his voice suggested anything unusual. Normal chitchat, good-bye.

I placed my usual call in the evening. Louise said Lefty wasn’t there, she didn’t know where he was.

I called the next morning. Louise said Lefty hadn’t come home, she still knew nothing.

I called Case Agent Jerry Loar in New York. I told him that Lefty was missing. He said they had received word from two informants that three Bonanno captains had gotten whacked the night before: Philly Lucky, Sonny Red, and Big Trin.

The three had apparently been summoned to Brooklyn to a “peace meeting,” to patch up differences, at a catering establishment. Our information was that’s where they were murdered. No bodies had been found.

The heart of the opposition to Rusty Rastelli and Sonny Black had been whacked out all at once. The other main rival, Caesar Bonventre, was in jail in Nassau County, New York, on a weapons charge. But the word was that he had decided to come over to Sonny’s side, anyway, and bring the zips.

Three days later Lefty called me in the afternoon. “I just got in.”

“Did you talk to Louise yet?”

“I called her this morning for two minutes, that’s all. You know why I come in, because she sent me all my clothes last night, whole box. She leaves the fucking pants out. She started crying at first. ‘What are you crying for?’ I says. ‘I got the clothes.’ ”

“I sent her a grand, you know, because I didn’t know how long you’d be gone.”

He had been holed up at Rabito’s apartment. “It’s gonna be a while yet, but let me throw a curve at you.”

“I’m listening, go ahead.”

“Everything is fine. We’re winners. A couple of punks ran away, but they’re coming back. They came back. We gave them sanctuary.”

“Is that right?”

“What we gotta do with you is, we gotta work out one more situation. I’m with that guy day and night. Have a little patience.”

“Yeah, well, I figured something was going on, so that’s why I just kept calling Louise. You don’t know how long you’re gonna be gone?”

“No. It’s just that I’m dead tired tonight, and I’ll be home the rest of the night.”

“You gonna stay in, then?”

“Ah, till I get a call. You know what I’m talking about.”

“Yeah.”

“Everybody is satisfied. Them two guys out at the beach—don’t mention names.”

“Yeah.” That was Joe Puma and Steve Maruca.

“They belong to us now. Now, don’t talk to me, Donnie. But visualize what took place.”

“Yeah, all right.” I visualized the hits.

“You understand?”

“I understand what you’re talking about.”

“Now they’re ours. How’s the weather down there?”

“It’s nice. Everything gets cleared up, maybe you can come down.”

“Well, we’ll see what happens. Right now I can‘t, I’m stuck over here. What’s happening?”

“I’m looking at something, you know, might be worth maybe about ten grand or something.”

“Ah, that’d be perfect, buddy. We can use it. I wanna clear up all these goddamn bills.”

“That’s why I figured I’d send that grand.”

“She appreciated it.”

“I figured you might be gone another five, six days.”

“Well, now it’ll be longer than that. Being that tomorrow’s Mother’s Day, everybody went home, you know. Everybody’s laid up. I gotta go see him tomorrow morning.”

“You still got another situation.”

“Yeah. All right, buddy, so long.”

Six days after the hits, the wife of Philip “Philly Lucky” Giaccone filed a missing-person’s report on her husband with the Suffolk County, New York, Police Department.

On Tuesday, May 12, Lefty called and said that Sonny wanted to see me right away. I told him I needed a couple of days to clear up some business, then I would be up. “It’s very important,” he says, “so let me know as soon as you make arrangements.”

I didn’t have any business to clear up in Florida. But even in this instance I didn’t want to seem too anxious. I was being summoned by Sonny for one of two reasons. Either I was going to be whacked, or I was going to be told about the hits and maybe involved in the “other situation” that was still left to take care of.

Either mission was crucial enough for me to make one arrangement, which didn’t take long.

I flew into La Guardia on the afternoon of May 14, got off the plane, and immediately saw the agent I was to look for, Billy Flynn. I followed him silently into the men’s room. He slipped me a wallet containing a transmitter. I dropped it into my sports coat pocket and went out.

I rented a car and drove to Graham Avenue and Withers Street in Brooklyn, and parked up the street from the Motion Lounge, arriving at about three-thirty. I didn’t park right in front because I wanted to walk and case the block.

In recent weeks I had been in regular telephone contact with Jules Bonavolonta at Headquarters. Jules and I had been street agents together in New York. Working undercover, it was important to have one guy on the inside that you could trust totally to understand you and your situation, somebody that you could talk to as a close friend yet who at the same time had the skills to maneuver within the bureaucracy. Jules had become that guy for me. He could handle internal politics, get me authorizations and support. I called Jules all the time with frustrations: “You ain’t gonna believe this,” I would say when I had run up against some starch.