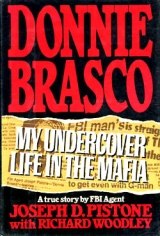

Текст книги "Donnie Brasco: My Undercover Life in the Mafia"

Автор книги: Joseph D. Pistone

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 5 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

5

BROOKLYN: THE COLOMBOS

The Acerg store was in the front, and anybody in the crew could act as salesman. There was a back room with a desk and a couple of card tables. That’s where the crew hung out during the day. That’s where I was introduced to a few guys, ranging in age from maybe late twenties to early forties, who were sitting around playing gin and bullshitting. First names and nicknames only: Guido, Vito, Tommy the Chief, Vinnie, and so on.

I started hanging out there with Jilly’s crew. Because I was “known” by other people that this crew knew, and because I was introduced to them by somebody they knew, they were pretty open around me.

Although these were lower-echelon guys in the mob, they always had something going. They always had money. They were always turning things over. They always had swag around. Swag was always going in and out. Everybody dressed well. Ninety percent of what they wore was swag. Latest styles. Sports shirts, slacks, sweaters, and leather jackets. If they had jeans on, they were always designer jeans.

You name it, they stole it. Jilly’s crew would hit warehouses, docks, trucks, houses. There was nothing they wouldn’t consider stealing. They considered all the time. There wasn’t one hour of one day that went by when they weren’t thinking and talking about what they were going to steal, who or what or where they were going to rob. There was always a load to go after, or somebody else’s load you might get a piece of, always something to hustle.

When they got up in the morning, they didn’t think about going to work and punching a time clock. They didn’t think about spending time with their wives or girlfriends. The mob was their job. You got up, went to the club or wherever you hung out, and spent your day with those guys.

You’ve got to be up all day figuring out what you’re going to do that night, what scores you’re going to go out on. The day basically was: You got to the club at ten-thirty or eleven o‘clock in the morning, then sat around all day and discussed scams and scores and hustles, past and future. Somebody would have an idea about a burglary or hijack, and they’d kick it around to see if it was worthwhile. Or somebody else had pulled a score and was looking to get rid of jewelry, furs, or whatever. And they’d discuss the possibility of “middling” it—taking the swag and reselling it.

All day long, while they schemed, they’d sit in the back room at the Acerg store and play gin and smoke cigarettes and cigars. I don’t smoke. They never opened a window. Even with air-conditioning, it got to be pretty dense. There might be two games going, depending on how many guys were in there. I don’t even like to play cards. You play gin—never any other game—for maybe ten cents a point. Even while you’re sitting around playing gin, you’re still talking about making a dollar, what the hustle of the day is. Maybe you go over to somebody else’s club, play gin there, or talk up some scheme. Maybe you talk to somebody about a score you’re trying to set up or trying to get a piece of. If they had a potential job to case, a couple guys would go out during the daytime and look it over.

If they weren’t scheming and dreaming, they were telling war stories, reminiscences about their time in various jails and prisons. Everybody did time in the can. It was part of the price of doing business. They knew all about different jails, cell blocks, guards. I had enough phony background set up to establish my credentials as a serious criminal, to show that I was tough enough to do time if I had to without turning rat. But I never claimed to have done any prison time because I didn’t know those places, and that could have just tripped me up. If you do three to five years you get to know the guards—what guard’s on what tier. You get to know the inmates, guys who are doing fifteen to twenty, guys who are still there. They knew the lingo and the slang. Everybody remembers those relationships and that time.

My thinking is, if it’s not necessary to have done something, don’t claim to have done it. When these guys talked about prison time, I just listened like an ordinary citizen.

For lunch somebody would go out to bring in Chinese food or hero sandwiches. Maybe around four-thirty or five o‘clock, the guys would split, go home to their wives or whatever, have supper, then go back out on the street, pulling off their scores or bouncing around the night spots or doing whatever they did.

On Tuesdays we went to Sally’s club for lunch. Sally was an old-time wiseguy, a capo in the Colombo family. He had a social club on 17th Avenue, not far from Jilly’s. Sometimes we’d hang out over at Sally‘s, divide the time between there and Jilly’s. But every Tuesday afternoon Sally cooked a big lunch for our whole crew of about eight, and his own, altogether maybe eighteen or twenty guys. He had a regular kitchen, and he would cook meatballs, macaroni, sausages, peppers, everything. For this lunch we would set up a long folding table. We would sit at the table all afternoon eating lunch, drinking jugs of homemade red wine that Sally produced, and bullshitting.

My day would pretty much follow the same routine as theirs. I’d get to the club between ten and eleven and hang out all day with these guys. By late afternoon or early evening, I’d go back to my apartment, maybe take a nap for an hour, get up and shower, and about nine o‘clock or so go back out on the street to wherever it was we were going to meet. Sometimes I would go back to Brooklyn, sometimes bounce around in Manhattan; sometimes with them, sometimes by myself in places where people had gotten to know me through these guys.

But even when we’d cruise around to the different night spots, the talk was always on whatever scams or hustles were going on or coming up. What they did for a living was on their minds more than it was with ordinary people. They never put that aside. Nobody ever had enough money, no matter how much they had, and it was always feast or famine. Half the time their schemes came to nothing. Or worse, they went bad in the execution and cost them either money or jail time. But that didn’t cool their dedication. They did not have a sense of humor about their failures, or those schemes they came up with that were hare-brained. They stuck to their routine.

A small-time fence named Vinnie, who hung around Jilly‘s, was overweight and had a bad heart, for which he took some pills—maybe nitroglycerin. One afternoon we were all in a card game. It was a hard game, for quite a few bucks. And at the same time they were kicking around the prospects for a house burglary over in Bayonne, New Jersey.

All of a sudden Vinnie falls down on the floor, gasping for breath and grabbing at his chest.

“Hey, you guys,” I say, “Vinnie’s got a problem.”

Nobody moves. They keep playing cards. Vinnie is gasping and grabbing, and still nobody moves.

“He’s having a heart attack!” I scramble over to him. “We gotta get him to the hospital! Come on, somebody help me with him!”

“Aw, he does that all the time,” one of the guys says. “He’s just having one of his regular attacks. Let him pop a few pills, he’ll get over it.”

This was one of the situations that often came up where I wanted to fit in with the badguys, but I still had my own sense of morality.

I can’t just let the guy croak. I manage to get him up and out to my car. I drive him to the emergency room. A couple of hours later he comes out. “I ran out of my medication,” he says.

We drive back to Jilly’s. They are still playing cards. “See?” somebody says. “We told you he’d be all right.”

It was easy to get lulled by this daily routine with these guys. Most of the time it was boring. They were not Phi Beta Kappas, but they were very streetwise. Just under the surface of their routine there was always something lurking that could trip me up. While I was constantly taking mental notes in order to report relevant information to my contact agent, I had to be alert for traps. Most of these guys were, after all, killers.

The FBI wouldn’t let me actually go out on hijackings and burglaries, because the crew went armed. There was too good a chance somebody would get shot. In these pioneering days, thinking upstairs in the bureaucracy was very conservative. Somebody suggested that if I went along on crimes where guys were packing guns, I might be liable for prosecution myself.

The guys would ask me to go out on jobs with them. I would find ways to back off. I would tell them, “Hey, packing a gun and all that stuff, that’s too cowboy for me. I’ll help you out later on with the unloading.” And they had enough guys so that adding me didn’t mean anything. It wasn’t like I was crucial. Plus the fact that for every man that doesn’t go along on a job, that’s less split they had to do on the proceeds.

They bought it. But if I had tried to push for myself to go along, get all the information I could about the score, and then back out of it—that would have made them very suspicious. I was always up-front with them. I stayed low-key, and it was no big deal that I was around.

But once they got a little used to me, they let me sit in on their planning sessions. I’d go out with them when they cased a score. And gradually I started imposing myself. They would come and ask my advice on certain scores. I would sit down with them and go over the plans of the job, pick out flaws in it. That showed them that I knew something about what I was doing. In some cases when I could show them what was wrong with pulling a job, it deterred them from pulling them—part of my job, after all.

It was a delicate situation. I couldn’t initiate or encourage crimes. Yet to be permitted to hang around I had to participate in some fashion. The Bureau didn’t have any firm guidelines for everything I could and couldn’t do. I was pretty much on my own. It required some tap dancing.

I helped unload stuff at the store. They would hijack any kind of truck, from eighteen-wheelers down to little straight jobs. They would seize the truck, unload the stuff into smaller trucks or vans, and take it to the “drop,” which might be a vacant warehouse or factory, and bring samples to Acerg to show prospective buyers. The load would be parceled out to fences who could get rid of it.

When they hijacked a truck, they would usually just tie the driver up. But most of the hijacked loads were giveaways—setups. The drivers of the heisted trucks would be in on the heist for a percentage. The crew would go wherever they got the information that a guy had a good load on. Most of the heists were in the city. They’d pull them right on the streets in Brooklyn. Some were in Jersey.

Their burglaries were all over—in the city, out on Long Island, over in New Jersey, in Connecticut, in Florida. Stuff came from the airports all the time. Jilly had a steady supply from JFK International Airport, utilizing somebody inside the cargo operations.

I’d unload cases of coffee, sugar, frozen food, whiskey, bags of cocoa, truckloads of sweaters, blouses, jackets and jeans. They would take anything. The best loads were food loads—shrimp, coffee, tuna—because you can get rid of that stuff anywhere, like restaurants and supermarkets. Frozen shrimp and lobster were favorites. Pharmaceuticals—over-the-counter stuff like razor blades, aspirin, toothpaste—were prime targets because so many stores wanted them and the markup was great, even on the straight market. Clothes were good, especially leather, and women’s clothes. Liquor was always a big item, especially around Christmastime. There were women’s leather gloves, ski gloves, even a load of hockey gloves.

The commodity didn’t make any difference, as long as they could sell it. Now, something like men’s hockey gloves—where would you move them? They might have gotten stuck with them. But it was a load they could take, so they took it. It doesn’t cost anything to steal hockey gloves.

Managers at places like restaurants and supermarkets had to know the stuff was hot, because the price was below anything on the wholesale market. But they bought it, anyway. Some of the best places. When you see how that works, it changes your view of some of the bargains and discount stores. It makes you more cynical. Sometimes the circle was very neat. They would burglarize an A&P warehouse one night, sell the cases of coffee and tuna to other stores a couple of days later.

TVs and VCRs were big. Robbing boxcarloads of them from the railroad freight yards was nothing unusual. They had a railroad employee who would give them a bill of lading and point out the right boxcar. Just back up a truck and load it.

When they hit houses, they were usually looking for jewelry, stocks and bonds, cash, or guns.

Anything that wasn’t tied down, they would steal. Those were the days when Mopeds—motorized bikes or motor scooters—were popular. They would steal Mopeds off the street and rent them by the day out of the store.

I maintained a low profile, the way I’m comfortable. I didn’t volunteer more about myself than was necessary ; I didn’t ask questions that didn’t need to be asked—even though information I wanted was often just out of reach. But I knew that certain things I did would catch the eye of people or have people talking. I had to be patient, just let things develop.

Guido was Jilly’s right-hand man, and he was a tough guy. He was tougher than the other guys in this crew. He looked different too. An Italian with blond hair and blue eyes. He had a mustache. Because he wasn’t a made guy, he, like me, could have a mustache. He was about 6’1”, 200 pounds. Late thirties. His arms were tattooed with snakes. He wore tinted glasses. He told me he had been in and out of jail most of his life, for various offenses. He was a shooter, but he had never been convicted of murder. Guido’s crew under Jilly was sophisticated enough to operate with walkie-talkies. Jilly told me he thought Guido was too much of a cowboy, took too many risks, but that he had done a lot of “work” for the Colombos, meaning he had participated in hits.

If Guido was your friend, he would be with you till the end. If he was your enemy, forget about it—he would get you. Everybody showed respect for Guido.

One day soon after I started hanging out with the Jilly crew, Guido and I were riding around in my car.

He said, “Hey, Don, what’s that squeak?”

“I don’t know,” I said. “Doesn’t bother me.”

“Yeah, it’s a squeak,” he said, leaning forward and cocking his head, “in the dashboard.”

We got back to Jilly‘s, and I pulled up at the curb across the street.

He said, “I’ll take that dashboard off and find that squeak and fix it.”

“Hey, Guido, don’t waste your time. It don’t bother me.”

“It bothers me. It won’t take long.”

Guido always carried a set of burglar tools in a toolbox in his car. He went and got them and crawled in under the dashboard and started taking it apart.

I said, “Why go through all this trouble just to find a squeak? It’s no big deal.”

In five minutes he had the whole dashboard off. He looked all over behind it. “It’s okay,” he said. He started putting it back in place.

“Well, what the hell did you take it apart for?” I said.

“To tell you the truth, you’re new around here. I just wanted to see if your car was wired up or anything. It’s clean.”

“Well, fuck you,” I said. “You think I’m a fucking cop with a fucking recorder in my car? Why don’t you just ask me, face-to-face?”

“Take it easy, Don. We gotta be careful, that’s all. There’s lots of operations they got going on around here. You’re just new to us, that’s all. Forget about it.”

Actually I wasn’t all that surprised to have somebody snooping around to check me out. If they did it once, they could do it again. So for all the years I was on this undercover job, while I would eventually have reason to wear hidden transmitters and tape recorders and would ride around in other agents’ cars which were equipped with recorders, I would never have my own car wired.

I couldn’t play it entirely safe. Any chance I would get, I myself would snoop around. If the guys were out front in the store or outside, and I was alone for a couple of minutes in the back room, I would always be looking in the desk drawers. There would usually be guns, both automatics and revolvers. There would also be other burglary paraphernalia stashed in there, like wigs and ski masks. If anybody had come in, my snooping would have been fatal. But my job was to find out what was going on, after all. I wasn’t just curious.

If I was who I said I was, I couldn’t just be sitting around listening to their schemes. I had to have some things of my own going.

Early in 1977, I made a few small deals with Vinnie the fence. Vinnie wasn’t a heavy-duty guy. He was a family-type guy, from Staten Island, who used to hang around Jilly’s during the day and then go home to his family at night. He didn’t go out on actual jobs; he wasn’t a tough guy. He just got rid of swag for people.

I wanted to make it look like I was moving stuff here and there to make a few bucks and trying to work my way up the line to bigger fences. Vinnie started me out with perfume.

We arranged a meeting for downstairs from my apartment, outdoors at the corner of Ninety-first Street and Third Avenue. Around noon he arrived driving a rented white Ford Econoline van. It was filled with cartons of perfume—by Lanvin. “I pick this up every week right at the factory where they make it,” he said. “I pay a couple of guys who work there.”

Perfume wasn’t really my line, but it’s not too far removed from jewelry. And mob thieves don’t turn up their noses at anything where they can make a profit. You want to be a good customer, but not so good that you become a mark. I bought one carton of the perfume—Eau My Sin and Yves St. Laurent Rive Gauche—for $220.

The perfume, like everything else I bought in my role, I turned over to the FBI.

A few days later I met him at the Woodbridge Auction on Route 9 in Woodbridge, New Jersey. The auction was like a flea market and drew big crowds. Vinnie had a booth there where he sold swag that he hadn’t sold to other fences. There, with the public and families all milling around, Vinnie would be in his booth selling stuff from hijacks or burglaries. I used to swing over there to see what new stuff he had, or if I had something that he might want to sell out of the auction. He got rid of a lot of swag from that booth.

I even took my wife there once. I got to spend so little time with her in those days that I figured the risk was tolerable. She got a kick out of it. The only problem was that once, right in front of Vinnie, who called me “Don,” she called me “Joe.” But he didn’t seem to pick up on it. And, anyway, supposedly she was just some broad I knew—I could have been using any name with her.

He had some Enigma perfume for me, $250 a case, which contained fifteen boxes. “This stuff retails for forty dollars a box,” he said. I bought a case.

I told him I had made a score, and had fifty to sixty watches and a good haul of fine turquoise jewelry. I showed Vinnie two sample wristwatches—gold Pateau Mitsu Boshi Boeki digitals, which were fairly new at the time, with red faces, worth maybe $80 apiece—and he bought them for $20 each. “I’ll show these to Jilly in Brooklyn,” he said, “and see how many more he wants.”

Most of the “swag” I sold was stuff confiscated by the Bureau, loot recovered from previous thefts but which could not be traced back to the owners. These watches and jewelry were not from the Bureau. I had wanted the stuff in a hurry to make this deal, so I had bought them at a wholesale place on Canal Street. I worked it this way a few times. It meant there was no paperwork, nobody would know where the stuff was going. Like some other things I did, it might have left me open to internal criticism, but I had to make the decisions about my own security and pace. And nothing I did was a shortcut that would damage a case.

Vinnie said that he and his partner were about to make a score on a load of Faded Glory jeans, for which a buyer had already agreed to pay $125,000. “The load is a hundred and twenty-five thousand pairs,” he said, “so it comes out to a buck a pair.”

Three weeks later he called and said he wanted fifteen more watches, which I sold him for $300, and some of the turquoise jewelry. I sold him necklaces and bracelets for $150.

I said, “Did you get that load of jeans?”

“Part of it. The guy who took it, he made a couple other deals. So we only got part. You know how it is.”

These small deals helped me get accepted by the crew at Jilly’s store and by the people they associated with. One of the first things Jilly himself offered me was a white sable coat, part of the haul they had taken in a burglary the night before. “It’s worth eleven grand,” Jilly told me. “You can have it for twenty-five hundred bucks if you want it.”

I passed on that, told Jilly I didn’t think I could move it.

There wasn’t any sense in buying anything expensive that I couldn’t identify, couldn’t eventually trace back to the owner. If you can’t trace an item back to the owner, you can’t prove anything in court. Jilly didn’t tell me where he got the coat, and you don’t ask somebody where they got something like that. Unless he had, say, seven or eight of them—a really big score. Then you might say, “Hey, where’d you make a score like that?”

At that point the only reason I had for buying the stuff was to establish credibility, as I’d done with the perfume. But I didn’t need to spend $2,500 for credibility.

The crew was either talking about, or bringing in, loads every day. Price isn’t always negotiable. Even if a potential buyer feels that the price is too high, that doesn’t mean the sellers will drop the price. The high price probably means that they have to give somebody else an end of it: Whoever they got it from wants x amount of money, so for these sellers to make anything they have to put a few bucks on top of that, and they can’t really drop the price. No deal is ever really dead, it just keeps being shopped around.

Tommy the Chief was a fat hood, probably in his fifties. He brought in a case of crushed salted almonds, the kind used in making ice cream. He told Jilly he had fifty-eight more cases in his cellar, stolen from Breyer’s Ice Cream in Long Island City. He had a list of other stuff he said he could get—cocoa, dried milk, and so on, from Breyers. “We got it set up with one of their guys that works as a roaster inside,” Tommy said. “And we also got the security guard who will be on duty when we go in next week. The haul will be worth a hundred G’s.”

Jilly decided to go for it, to rent three twenty-two-foot trucks to haul the stuff away, and a garage to store the swag in over the weekend, until it was moved to the buyer. They brought one truckload of cocoa to the club. They just parked the truck right on the street, and I helped unload it. In that neighborhood, who’s going to say anything about what goes on at the Acerg store? Two days later the load was sold to some guy in Yonkers.

One night Guido took a crew to burglarize a warehouse. They were going to heist four thousand three-piece men’s suits. They had some kid with them to be the outside man, the lookout. While they were inside, somebody tripped a silent alarm. The owner arrived at the warehouse. The outside man panicked and took off without notifying anybody inside. The crew heard the owner coming in and managed to sneak out the back.

When Guido was telling Jilly this the following day, I wondered what the punishment might be on the kid. The crew boss had a wide range of options. Punishment depended on who the boss was and what kind of mood he was in. If Jilly was really ticked off, they might do a bad number on the guy.

Jilly decided they would go back in the next night. As for the lookout, all he said was, “I don’t want that cocksucker with you when you go back in. He can’t come around no more.”

They went back into the warehouse. They didn’t get all four thousand suits. They got about half of them.

I was always on the lookout for an opening to get to the bigger fences, the guys Jilly’s crew was selling to. But whenever I’d suggest that I might be able to use a couple of contacts, they’d say something like, “Give it to us, we’ll bring it to the guy. Don’t worry about it.” And if I said I might have some big score coming, their reaction would be, “Hey, you got a big load, we can get rid of it for you.” They weren’t about to give up their fences.

There was no acceptable reason for me to push to meet the bigger fences, except by coming up with bigger swag to sell.

I wasn’t spending all my time in Brooklyn. I kept poking around in other directions. While bouncing around the Manhattan night spots with the Colombo guys, I met Anthony Mirra. I was introduced to him in a disco then named Igor‘s, which later became Cecil’s, on Fifty-fourth Street.

I knew who Tony Mirra was. He was a member of the Bonanno crime family. He had done about eighteen years in the can for narcotics and other convictions, and he had only gotten out a year or so earlier. I knew that he was involved in anything and everything illegal to make money—gambling, drugs, extortion, and muscle of the type that leads to “business partnerships.” I knew that he was a contract man, with maybe twenty-five hits under his belt. He was mean, feared, and well connected, a good guy for me to know.

I started hanging out with Mirra while I was still running with the Brooklyn guys. Through Mirra I met a good thief. I needed some more potent swag to bring to Jilly’s crew. This thief had a haul of industrial diamonds. I decided to take a shot with these diamonds. I asked the thief if I could take a few samples on consignment to see if I could “middle” them—be the middle man for selling them off. He agreed and gave me ten diamonds.

Selling stolen property like this would not have been sanctioned by the Bureau. I didn’t want to argue with anybody about it. I decided it was worth the chance.

The diamonds I had were worth about $75,000 on the street. I didn’t really want to sell them to Jilly’s crew, I just wanted to show them what I could do. I decided on a price that would be higher than a good street price—to discourage the sale—but not so high that it would look like something was wrong or I didn’t know what I was doing.

I brought the pouch of diamonds into the store and showed them to Jilly and the guys.

“I hit a cargo cage out at the airport,” I said. “I got a guy inside. I give him a cut. I got a buyer already, down on Canal Street. But if you could sell them, I’ll give you the shot. All I want is a hundred grand out of the deal—seventy—five thousand for me and twenty-five thousand for my inside man.”

“That’s kind of high,” Jilly said, “a hundred grand.”

That price would force them to ask for $150,000 to $200,000 in reselling them.

“Hey, what can I tell you?” I said. “My inside guy that set it up wants twenty-five grand. The guy on Canal Street is willing to give me a hundred grand. I’m giving you a shot because I’m with you guys. I need seventy-five grand. So if you could sell them for more than a hundred, anything over that is yours.”

Jilly said to give him a couple days to check with a guy who was out of town. I did. He checked with the guy and said to me, “He’s willing to go for seventy-five.”

“I can’t do it, Jill. I would only get fifty thousand out of the deal, and it’s not worth it. I’ll just off ‘em to the guy down on Canal Street.”

“Yeah,” he said.

Jilly understood, which was just what I wanted. I had made some moves, got some stones—no cop is going to come up with $200,000 of diamonds to sell—showed them that I knew what I was talking about. If Jilly had come back with an offer of, say, $125,000, I couldn’t have backed out of the deal. I would have had to keep my word and sell them to him. That was the chance I took.

It gave me a jump up in credibility, up from the ground floor.

When I first met Jilly, he wasn’t made. Nobody in that crew was. He told me he had grown up in Brooklyn, had been stealing all his life. His dream was to get made, become a true member of the Colombo family.

One morning in early May, I arrived at the club to see Jilly all dressed up—pin-striped suit, dark tie, the works. You don’t usually hang out in a suit and tie. He looked excited, strutting around. He also looked nervous.

He was just leaving when I came in. “Jill,” I said, “where you going dressed like that?”

“I gotta go somewhere,” he said. “I’ll tell you about it later, when I get back.”

He left, and I turned to Vinnie. “What the fuck’s going on?”

“He’s getting his badge today,” Vinnie said. “He gets made.”

We waited all day for Jilly. When he came back, he was ecstatic, as proud as a peacock. “Getting made is the greatest thing that could ever happen to me,” he said. “I been looking forward to this day ever since I was a kid. Maybe someday you’ll know how it feels. This is the fucking ultimate!”

“Hey, congratulations!” I said. “Who you gonna be with?”

“Charlie Moose.”

Charlie Moose was going to be his captain. “Charlie Moose” Panarella was well-known to law-enforcement people. He was a mean guy, an enforcer. He was a high-ranking captain, and Jilly would now be a soldier in Charlie Moose’s crew, and Jilly couldn’t have been prouder.

That night we all partied together for his celebration. But now everybody treated him with more respect. He was a made guy now.

To become a made guy, to a street crook who is Italian, is a satisfaction beyond measure. A made guy has protection and respect. You have to be Italian, and be proposed for membership in the Mafia family, voted on unanimously by bosses and captains, and inducted in a secret ceremony. Then you are a made guy, “straightened out,” a wiseguy. No one, no organization, no other Mafia family can encroach on the turf of a made guy without permission. He can’t be touched. A Mafia family protects its members and its businesses. Your primary loyalty is to your Mafia family. You are elevated to a status above the outside world of “citizens.” You are like royalty. In ethnic neighborhoods like Jilly‘s, nobody has more respect than a made guy. A made guy may not be liked, may even be hated, but he is always respected. He has the full authority and power of his Mafia family behind him.