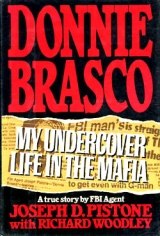

Текст книги "Donnie Brasco: My Undercover Life in the Mafia"

Автор книги: Joseph D. Pistone

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 18 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

I called Sonny back and told him that Chico was interested but couldn’t get up there for a couple of days. Sonny was impatient. He didn’t know anything about dealing this kind of stuff and didn’t want it lying around. We didn’t want to make it look like we were too anxious, that Chico had nothing to do. Sonny said he’d wait.

Chico hooked up with another agent from Chicago who posed as a shady art dealer, and they flew to New York.

Sonny picked them up at La Guardia Airport and, after making some quick turns to clean off possible tails, took them to Staten Isla where the stolen artwork was stashed. The stuff looked impressive—trays and relics of gold, good paintings. Chico took Polaroid pictures of everything, explaining that it was necessary to study the photos and check out the goods for “provenance”—to prove their authenticity.

A few days passed. Still there was no report of any theft. Chico passed word to Sonny that his man couldn’t find a buyer right now. Sonny started to sell some pieces off. There was nothing we could do. The FBI couldn’t seize the goods without revealing our operation.

Sonny came to Florida to pursue some contacts that might lead to an introduction to Trafficante.

Rossi and I were having breakfast with Sonny in the coffee shop at the Tahitian. Sonny brought up the matter of the Shah’s artwork.

“We took over a hundred grand,” he says, “and they didn’t even know it was missing.”

But then they had tried to burglarize the town house owned by the Shah’s sister on Beekman Place, one of Manhattan’s most exclusive neighborhoods. They had a man who supposedly had taken care of the security guards. Sonny waited in the car while a couple others went upstairs to pull the job. He heard a shot and took off.

He went back to his club in Brooklyn. Soon the burglary team showed up. One of them had shot himself in the hand. There had been a scuffle with a guard, and the whole thing was blown. Sonny sent the guy to their regular doctor around the corner, then gave him $500 and told him to get lost for a couple of weeks.

“It was fucking close to a billion-dollar score,” Sonny says. “I don’t even want to talk about it.”

But there was hope because the Shah, who was in Egypt, was fatally ill and would die soon. And when he did, Sonny wanted us to shoot up to New York because they were going to hit that warehouse again.

“You come running right down, brother,” Sonny says. “Take a fucking fast jet. We’ll get all this guy’s stuff when it comes from Egypt.”

But when the Shah died a few weeks later, Boobie called me and told me that the whole thing was on hold.

Angelo Bruno, the longtime boss of Philadelphia, had been hit—the second major boss to be rubbed out in a year. He was sitting in his car when somebody put a shotgun behind his ear. I asked Lefty about it.

“Bruno wanted all of Atlantic City,” he says. “He already had all the services at the casinos, but then he wanted all the gambling. You can’t have all of Atlantic City. The Gambinos got interests there. Trafficante’s got interests. Santo gave Bruno a piece of Florida in exchange for a piece of Atlantic City. We got interests over there. See, when you do things with people, you share. Especially whatever you do in the family, Donnie, you share with your people. In our family, the reason Lilo got whacked is that he wouldn’t share his drug business with anybody else in the family.”

“Is that right?”

“Hey, listen carefully, Donnie. If they can hit a boss, nobody’s immune.”

14

COLDWATER

The FBI had had Santo Trafficante under surveillance for some time. With the prospect of bringing the Bonannos together with Trafficante, Project Coldwater continued that surveillance and added electronic devices at King’s Court. The club had hidden videotape cameras that could monitor the office and the private round table in the main room that Rossi used. There were bugs in the chandelier over the round table and in the telephone. Rossi’s car had a Nagra tape recorder hidden in the trunk.

I moved into a one-bedroom, second-floor apartment in a complex of four-story buildings called Holiday Park Apartments directly across Route 19 from King’s Court, where Rossi also had an apartment. From my window I could see King’s Court. My telephone was wired for recording. Earlier in the Mafia operation, in Milwaukee or Florida, when I had wanted to record a conversation over a phone, I had done it with a simple suction-cup microphone attached to the handset and a regular tape recorder. Now that I had an apartment, I would have visitors, so I couldn’t have any recording devices lying around. A recorder was hidden inside the wall and hooked directly into the telephone line.

On occasion, Rossi or I would wear a “wire,” either a Nagra tape recorder or a T-4 transmitter.

The Nagra I used was four-by-six inches, three quarters of an inch thick, and used a three-hour tape. It recorded only, with no playback capability. The microphone, about the size of a pencil-tip eraser, was on a long wire so that you could hide it anywhere on your body. The recorder had an on-off switch. Prior to using it, you could test it to see that the tape was rolling. But without pulling the tape and putting it on a playback machine, you could not test it for recording.

The T-4 transmitter was half the size of the Nagra recorder—3½ x 2 inches, a quarter inch thick. It had no recording capability of its own. It transmitted sound to monitoring agents positioned in the vicinity who could listen and record. There was no on-off switch. It had a small flexible antenna, one to two inches long, with a tiny bulb on the end, which was the microphone. When you screwed on the antenna, the transmitter was turned on. Fresh batteries lasted about four hours. You could test the transmitter ahead of time by getting a monitoring agent on the phone and asking him if he was picking up your radio transmissions. But as with the Nagra recorder, once you were out on the job, there was no way of telling whether the system was working.

An advantage of the Nagra was that you could record a conversation anywhere without backup agents. The advantages of the transmitter were its smaller size for concealment purposes, and the fact that when you were using it, there were monitoring agents nearby getting direct communications from the transmitter. With a transmitter, if a situation went bad and the undercover agent was in immediate danger, the other agents could be on the scene in moments. With a Nagra you could get in trouble and nobody would know.

But whereas you could record anywhere with a Nagra, in the city the transmitter had a broadcast reach of maybe two blocks. Steel structures could interfere with transmission, as could atmospheric conditions or passing vehicles. The surveillance team could lose you or get out of range. One danger was that it was possible for a T-4 transmission to be picked up and broadcast back over a television set. You could be sitting in a room chatting with a couple of wiseguys when suddenly the TV is broadcasting your conversation back at you. Everybody in the room knows that somebody is wearing a wire.

A disadvantage to any recording or transmitting device was that you risked your life using it. To be caught wearing a wire was usually a death sentence. Also, they didn’t always work. It looks easy in the movies. Just tape the device to your body, go in, and record the incriminating conversation. In reality the devices, while they are supposed to be at or near state-of-the-art in technology, are not infallible. There is always a compromise in efficiency when you try to make things small.

We undercover agents were not always given the equipment with the ultimate in advanced secret technology—stuff that spies may have. Eventually we testify in court, and we have to reveal the details of the electronics equipment we used in the investigation. Spies don’t go to court, so what they use won’t be revealed. Electronic stuff that the government wants to keep secret will not be given to undercover agents to use in making cases that go to court.

All these devices have delicate recording capabilities. That means that they pick up all sound. A device hidden on your body will pick up your own belches, the rustling of your clothing, and everything else in a room or nearby-conversations, shuffling of feet and chairs, radios and TVs, air-conditioners, street noise. Because of their paranoia that there are bugs planted everywhere, mob guys, whether in hotel rooms or cars or wherever, always turn on the TV or radio to cover the conversation.

Then, if everything else is just right, you still can’t insist that people talk about what you want them to talk about when you want them to talk about it. Our rules governing recording and transmissions were that once you’ve turned a device on, you leave it on for an entire conversation, and that conversation-recorded over the telephone or on the scene or by other agents monitoring your transmissions-is turned in as evidence. It doesn’t matter whether the conversation turns out to be irrelevant or whether it contains irrelevant sections; the whole thing is provided to the courts. While only relevant parts of conversations may be presented as testimony, the entire conversations are available to the defense attorneys so that they can’t claim we were being unfairly selective—trying to distort conversations-in what we recorded on the scene.

You turn on the recorder or transmitter prior to arriving at the scene. It may be hours before the conversation gets around to what you want to hear. Tapes run out. Batteries run down.

You have almost no control over conditions. You can’t test on the scene for sound levels. You can’t arrange people as you would like to for recording. You can’t ask them to raise their voices. You can’t control extraneous sounds that muddy the reception. You might go through hours of conversation laying the groundwork for the conversation you want. Finally he’s telling you everything you want to know. Then when they play the tapes at the Bureau, you got only half the conversation or maybe nothing—you don’t know that until it’s over. You can’t reconstruct that conversation. You can’t go back to the badguy and say, “You remember that conversation we had yesterday? Let’s talk about that again, and this time let’s not walk by that same building because there’s too much steel in it.... And let’s not walk too fast because the car that’s recording this is getting out of range.” Or,

“Let’s go over it again because last time the batteries were bad or the spindles were worn or the tape was dragging.”

That kind of frustration was to me more of a burden, more pressure than all the other undercover work.

I didn’t like carrying any device. It was difficult to hide anything. I was in solid with these guys, and there was always the traditional hugging and kissing of cheeks. There was horseplay, wrestling around. I was with these guys day and night. With Lefty it was twenty-four hours a day. I stayed in hotel rooms with him, changed clothes in the rooms, stripped to swimming trunks to go sit around the pool.

When I did use a recorder or transmitter, I never taped one to my body. The only time I did that was way back in 1975, at the beginning of the heavy-equipment theft operation. I carried the Nagra or T-4 loose, usually in my jacket pocket. With the Nagra I preferred not to risk running the microphone up under my clothes, so usually I wrapped the cord around the machine and stuck the whole thing in my pocket. When I wasn’t going to be wearing a jacket, I would put the Nagra in my cowboy boot. Then I would have to run the microphone cord up under my clothes and tape the mike to my chest.

I never wanted to keep the devices around. There was always a chance somebody would bust into your apartment or car. So when I wanted to use one, I made arrangements to meet the case agent somewhere for a pickup, and afterward for a drop.

The obvious overall advantage to wearing a wire is that you may get a crucial conversation that makes a case. That’s what makes it worth the risk. It was up to me whether I wanted to wear a wire or not in any situation. Altogether, beginning with Project Coldwater, I probably wore a wire a dozen times.

Sonny was pushing for an introduction to Trafficante. He sent Lefty down to Holiday on a mission to try to set up an introduction through intermediaries. We thought Lefty might talk about important people and procedures. It was too hot for a jacket. I put a Nagra in my cowboy boot.

He had told me that we were going to fly to Miami to meet the son-in-law of Meyer Lansky, the notorious mob mastermind of money and gambling businesses, who supposedly was a friend of Trafficante’s.

At breakfast I say, “I’m still not clear why we’re going down there.”

“Because I wanna see this guy,” Lefty says. “He’s in Miami Beach. He’s gonna introduce me to that guy there who’s going to introduce me to the main guy over here.”

Lefty was complaining as usual about Rossi not giving him enough money. Rossi had booked his round-trip flight from New York but had not offered to pay for his trip from Holiday to Miami, or for expenses he might incur.

“Just sit him down and explain to him what’s going on,” I say.

“That’s your job to tell him. This thing here is his idea.”

“I know it’s his idea, but he hasn’t made any fucking money yet, either.”

“I don’t need this aggravation. Just tell him we’re going to see Meyer Lansky’s son-in-law. Just tell him he’s got to give me the money.”

Lefty had sent Rossi over to the club to look for his Tampa-New York return-flight ticket. He said he had lost it somewhere. But he hadn’t lost it. He confided to me that he wanted to test Rossi’s reaction.

When Sonny had been down to see the club earlier, he had noticed that Rossi’s car had Pennsylvania tags and told Lefty he was suspicious about that. Lefty asked me, and I explained that it was a rented car, so the tags are whatever the car has on it when you pick it up.

But Lefty wanted to check him out a little more. Rossi had booked the New York-Tampa round-trip flight for Lefty on his American Express card. By pretending to lose the ticket, Lefty wanted to see how Rossi reacted. If he was an agent, Lefty reasoned, he would get nervous because he would probably have to account for the ticket to his office, plus he would be worried that somebody “in the underworld business” might meanwhile find the ticket and check out the American Express number to see if it was a government number.

When I had a chance, I clued Rossi in so he could end the search. He told Lefty he would just cancel the ticket and order another one.

We went to the club. Rossi says, “Nothing for nothing, Lefty, but just so I understand, you want me to pay for your ticket to Miami, right?”

“Well, who we going down there to see? I’m gonna see this guy in order to make a move out here. I’m not gonna make this move for myself. Once this guy gives you the green light, you can go anyplace you wanna go. That’s his father-in-law. I meet the old man, he calls this guy over here, and then I get a proper introduction. Now, you gotta give me my regular two-fifty to take back to New York. And a buck and a half to entertain this guy over there.”

“In other words,” Rossi says, “you’re gonna meet with old man Santo.”

“No, he’s over here. Gonna meet first old man Meyer Lansky. See, you can’t get an introduction to this man over here unless he sends you over here. He makes one phone call in front of me: ‘Hello, how are you? A dear friend of mine, he’s gonna visit you such-and-such a day at three o’clock.‘ Now I go here. I explain what I’m gonna do in this town. And this is the moves I want to make. I say, ’Do we have your blessings, or do we have to go further with it?‘ Most likely he’ll say, ’You got my blessings.‘ That’s the proper way of doing things. You can’t do it no other way. Now we clear all the middlemen out, all the bullshitters. Now you do what you fucking want in this fucking town. Ain’t nobody can approach you and say,

‘Hey you, what are you doing here?’ Know what you tell them? ‘Go see this fellow—if you can see him, which I doubt.’ “

“So you’re arranging a meeting,” Rossi says, drawing him out to get it on the tape, “with Santo.”

“That’s it, I’m making a whole fucking move. Listen. We stood three days in a fucking room-Donnie could tell you-in Chicago. Three days they made me lay in. Finally: ‘Come on, get in the limousine, let’s go.’ I didn’t know where the fuck I was going, but I got in the limousine. They took me to a big, big fucking cabaret. It was closed. It was the off-season. ‘Wait here.’ And from there went to a fucking restaurant. ‘Wait here.’ Then the main guy come out. He said, ‘Come on, let’s go in the office. You’re well recommended.’ And that was it.”

I say, “He wants to make sure that when we make these moves, we get protection from anybody that wants to come in.”

“I know that,” Lefty says.

“Not you, Left. I’m not talking to you. Tony’s got to know it.”

“The thing is, Lefty,” Rossi says, “nothing for nothing, but I gotta start earning.”

“Just a minute,” Lefty says. “Are we opening the doors for you right now? Another thing, we gotta get a tent for here. Free food, free drinks. Gambling in the tent. Why should you lose a Friday night business in the club? That’s the biggest mistake you made. And what about a Sunday afternoon?”

“We gotta operate in the bigger cities,” Rossi says, “like Orlando.”

“They own Orlando too. That’s the first thing I’m gonna get is Orlando.”

“And Tampa,” Rossi says.

“He owns Tampa. This is what the fuck I’m making a move for. I was with the fucking people all day yesterday, in New York.”

“Don’t misunderstand,” Rossi says. “I’m not trying to be disrespectful. I got a lot of respect for you. But I got to work hard in my life. Stealing ain’t easy today.”

“Well, let me tell you something, my man. Just a starting point. You just caught the off-season. You got the football season. Donnie’s going out and help you. You’re gonna have a lot of fucking action over here. You can’t close on Sundays, though, because Sunday’s your biggest fucking day.”

“But you still can’t go on betting on the fucking come, you know,” Rossi says. “Eventually you got to start earning. And the big money is still not here.”

“It’s in Tampa,” Lefty says. “And what the fuck you think we’re going to fucking Miami for? You think I like to ride in motherfucking planes? I don’t like restaurants, for number one. I don’t like traveling in a suitcase, for number two. Donnie knows what I like. Fucking weekends I’m home watching fucking TV, me and my wife. I don’t even want to go to a fucking joint. I don’t even go to Mike’s no more because I’m sick and tired of a fucking joint.”

“You understand what I’m saying.”

“I understand. All right, Donnie, go get your clothes. Let’s get the fuck out of here, do what we got to do. You know what I would like, Tony? I can make it myself. A nice cold spritzer.”

Johnny Spaghetti picked us up at the airport in Miami and took us to Joe Puma’s Restaurant, Little Italy, at 1025 E. Hallandale Beach Boulevard in Hallandale, just outside Miami. Joe Puma was a Bonanno guy who had been under Mike Sabella until the Galante hit, then was put under Phil “Philly Lucky” Giaccone. Lefty wanted me to meet Puma and Steve Maruca, another made guy. Maruca had recently been released from prison. He was more intimidating than Puma. He was a rugged-looking guy, about 6’2”, with a big voice and big hands.

Puma and Maruca were both under Philly Lucky. There was nothing wrong with us getting together with guys under another captain, but with the unstable circumstances of the Bonanno family at the time, I didn’t know what was up with Lefty wanting me to meet these guys, what it might mean, who was on what side in the factions maneuvering for control under Rusty Rastelli. But I knew that Puma and Maruca were important in the family.

Lefty was exploring another route to Trafficante, through a relative of Santo Trafficante’s. Supposedly he would introduce Lefty to the relative, who would introduce him to Santo.

Neither of the meetings came off. Both guys were out of town.

Sonny called and told me that he and Boobie were flying down for Memorial Day weekend. I call Lefty to tell him. That set him off about his turf.

“What do you mean, Sonny’s coming down tomorrow?”

“I don’t know. I asked him if he had talked to you, because I wanted to make sure you knew about it. He said, ‘Don’t worry, there’s no problem with Lefty, I’ll see him tomorrow before we go.’ ”

“I don’t believe this fucking guy over here. This is my fucking operation.”

“Left, I’m gonna be with you, you know that.”

“Ain’t the question. Why’s he coming down there?”

“Maybe he wants to come down for a vacation.”

“Don’t give me that fucking bullshit, maybe he wants. He ain’t supposed to be in that town without me. Who’s paying for his fucking plane fare?”

“I guess we are, but he said he’ll straighten it out tomorrow.”

“Don’t con me, pal.”

“That’s what he said.”

“Who the fuck are you to accept confirmation on his plane ticket?”

“Lefty, I’m gonna argue with him?”

“Yeah, you cocksucker.”

I hang up on him.

He calls right back. “You fucking motherfucker! You don’t hang up on me!”

I can imagine his veins bulging. “Don’t ever call me cocksucker, Lefty.”

“I call you what I want! I call you a cocksucker, a—”

I hang up.

He calls right back. “Lemme talk to Tony.”

I give the phone to Tony.

“That fucking son of a bitch cocksucker better understand who he’s talking to, Tony. Nobody treats me that way, hanging up. You better talk to that guy.”

“Lefty, I don’t know what you’re talking about,” Tony says.

“Lemme talk to Donnie.”

I get back on the phone and he resumes.

“I told you nobody goes on the expense sheet. You tell that motherfucker Tony that he owes me $500 and he sends me $500 tomorrow. I’m gonna shoot that motherfucker in the head. There’s something wrong over here, pal. I’m going to Brooklyn tomorrow and I’ll have all the answers. Who’s your fucking boss?”

“You are.”

“I’m your boss. I’ll get the answers in Brooklyn before he leaves. I want you by the phone at the club, twelve o‘clock. Make sure that other motherfucker’s on the extension phone. I want both you guys on the phone when I call.”

“I’ll make sure he’s there.”

“When I get through with Sonny, right then and there, if he can’t give me the right answers, I’m gonna tell you something.”

“What?”

“Ain’t nobody knows that I got three fucking grenades. Ain’t no motherfucker could ever live after I get through with them. If this guy gives me the wrong answers tomorrow, I’ll blow the fuck everybody up.”

“Lefty.”

Sonny and Boobie came down. They sat with Rossi and me in the lounge at the Tahitian. I had a Nagra in my boot.

“I don’t want to get caught in the middle with Lefty,” I say.

“I spoke to him,” Sonny says. “See, when I say to you, ‘Don’t say nothing,’ don’t say nothing. Lefty stood up for me when I was away. And I’d never do nothing to hurt him. He’ll go all the way with you. He’s a tremendous guy, a dynamite guy, but he tends to dramatize. He called me back after he talked to you. He was fucking whacked. Now, I don’t have to tell nobody what I’m doing. So you don’t tell him nothing. I’ll tell him what I want him to know. I’m never telling him what conversations take place. He knows me too long. I never do nothing underhanded. If I take down any money from here, he gets his end and he goes home to sleep.”

“He’s done a lot for me, too, in six years,” I say, “but I don’t want to have arguments with him over you. Anything we do, I’m always gonna give him a piece of my end. I don’t want him to think that I’m fucking him.”

“Donnie, you know the story with this crew. When I went away, they put me on the clothesline.”

“I know.” When Sonny was in the can, his crew had deserted him. He was separated from his wife, but he had four kids he wanted taken care of. Money supposed to go to his family wasn’t paid.

“They didn’t want to bother with me, this crew,” Sonny says. “They were afraid. But when the boss told him to keep his fucking mouth shut about me, he stood up. So now I come back home, the whole fucking story changes. Now we got all the power. So I brought him right back.”

“He’s a stand-up guy. There ain’t no two ways about it.”

“But you can’t tell him nothing. He gets them two fucking wines in him and then—well, he’s trying to help you, but he’s hurting you. Now, see, everything is politics. Five years ago, I give you my word of honor, I’m gonna put two guns in my fucking pocket for whoever calls me. But today you can’t do it. Today you gotta sit back and just go step by step.”

“That’s right,” Rossi and I say.

“You got all the kids coming around today, you know, and they’re stronger than lions. And all these old guys, they got a brain of a seventy– or eighty-year-old person. A seventy-year-old brain can’t compare with mine, because where he’s got like twenty more years experience in his day, I got like fifty more years experience in my day. And we’re living in my day, not their day anymore. That’s what they fail to understand.”

“That’s right,” we say.

“Like, who thought jeans were gonna be good? A young kid thought of jeans and look at the fucking money jeans are making. These old-timers will never wear a pair of jeans in their life. Their brain stopped. I’ll show you men that will go through a fucking tank for you, and I gotta give them a hundred, two hundred a week, and they ain’t earning a dime. All these big puffers with their cigars and pinkie rings, they’re taking down all the money. It’s gotta change.”

“Yeah,” Boobie says. He is looking around at some of the people passing through. “Those blondes is with somebody down here or what?”

“They’re just around,” I say, “far as I know.”

Rossi left the table for a few minutes. Sonny opened up more around me because Rossi was still considered an outsider.

I told Sonny that “our friend, the cop” had introduced Tony to a guy who owned shrimp boats and used them to bring in cocaine and marijuana.

“The deputy gave you this guy as a connection?” Sonny asks.

“Yeah. The deputy was with this guy a while back, protecting him for hauling marijuana. This guy does everything. We just met him, you understand. I told Tony, ‘Let this guy do all the talking. We don’t want it to look like we’re too anxious to do business. We just let him keep telling us what he wants to do.’ He said he was gonna come and see us a couple of months ago, but he wanted to make sure we were okay.”

“I don’t want to talk to Tony about it,” Sonny says. “If we do anything with this guy, you arrange it. We’ll take one piece and put it out on the street. Take us seven days. Whatever money we get, we’ll send up. Tell him the smoke is good because there ain’t that much involved. See, I got an army of cars to go back and forth from Orlando. Now, what we’re dealing with is a tremendous amount of trust in people. I only talk to you because you’re good, and you talk to me.”

“Right.”

“Down the line, these motherfuckers are weak. So don’t talk to nobody. I always talk alone, because the only way there is to get caught is talking with two other people. Because now there is a strict law. In other words, me and you are talking like now. They can’t pinch him over there for conspiracy with us because there’s just two of us. But there’s a lot of guys got five or ten years. We don’t trust nobody. We gotta get sneaky. Because the sneakier we are, the smarter we are.”

A few days earlier, Donahue, the deputy sheriff, brought up the matter of dog-racing tracks with Rossi. He wanted to know if Rossi’s people might be interested. Some politicians would have to be bribed. I brought it up with Sonny. “The cop told Tony his people are gonna come up with the bread, and they got a lock in Tallahassee, which is the state capital, for the license. He wants to help him put it together and for protection, so nobody else is gonna muscle in on it.”

“We could definitely protect this guy, down to the track. We gotta bring in another family, because that family controls over there.”

“That’s what I think he’s looking for.”

“Yeah, I’ll get that. Meanwhile I’ll come out with my top guns. Let’s hear what Tony’s got to say.” He waves for Tony to return to the table. “We’re talking about the dog track.”

Rossi nods. “He guaranteed that he’s got two investors around here, and each will put up a million dollars. But what he wants is protection, all what it takes in order to put this thing together.”

“What kind of help does he want? Protection from what?”

“He came to me because, you know, you couldn’t run a track here in Florida without Trafficante’s permission. That never came up directly. That’s what I read into it. He thinks I could, you know, reach out.”

“Yeah, well, that’s no problem. But who knows anything about putting a track together? That’s what we gotta find out. What is he actually looking for?”

“Sonny, all I do is listen. I didn’t say yes, no, nothing. There’s three dog tracks now, each one is open four months, so they’re all working with each other. Now, you put in this other track, you’re gonna have problems with those other three tracks unless there’s somebody there that controls it. So what he’s really looking for is the permission.”

“Or somebody,” I say, “that can go sit down with the guy in Tampa.”

“All right. I’ll lay it down to him when I see this guy, see what he says. If the guy says, ‘All right, go ahead,’ then youse go ahead, nobody will ever bother us. But if he says, ‘Listen, I got three, what do I need four for?’ Then forget about it. Because you gotta show him respect. The deputy was happy with that four hundred we gave him?”

“Oh, yeah,” Rossi says. “I give him money all along—two hundred, three hundred.”

“I mean, for that one night.”

“The Vegas Night? Oh, yeah.”

“We should tell him that we’d like to get another one in a few weeks time. I’ll bring the crew down, two guys for the crap table. This way maybe this time we could take down some real money.”