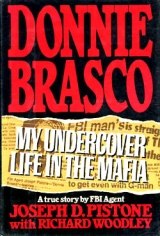

Текст книги "Donnie Brasco: My Undercover Life in the Mafia"

Автор книги: Joseph D. Pistone

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 7 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

Everybody in the joint turns away. Where wiseguys are concerned, nobody wants to know anything.

I say to the bartender, “You saw and you heard, right?”

“Yeah,” he says.

“So if anything comes down regarding this, just say how this guy was out of line. Fitz knows how to reach me and my people in New York.”

It turned out the guy was a member of the Lucchese family. Word did get right back to New York. Everything was smoothed over. It helped my image.

Fitz and I cruised the Miami-area hangouts that had been identified as likely places for contacts: Sneaky Pete‘s, Charley Brown’s Steak Joint, the Executive Club, Tony Roma’s, Gold Coast up in Fort Lauderdale.

But we weren’t able to lure the big-timers into conversation. For several months I went back and forth between the Colombos and the Bonannos, between New York and Florida.

Fitz and I were out one night in a nightclub near Fort Lauderdale. We were sitting at the bar. Fitz introduced me to a lot of people he knew in there. “This is Don from New York.” Guys were going into the john to snort coke. I was just sitting at the bar bullshitting with a couple of half-ass wiseguys and their girlfriends.

Then this one guy comes out of the john and comes over to me holding this little open vial. He holds it out to me and says, “Here, Don, have a snort.”

I smack his arm, sending the bottle flying and the cocaine spraying all over the place. I grab him by the lapels and hoist him. “I don’t do that stuff,” I say, “and you had no business offering it to me. Don’t ever offer it to me again. I make money off it, but I don’t use it. I keep my head clear at all times.”

“But look what you did,” he whines, “all my stuff!”

“Write it off to experience,” I say. “You wanna fuck up your head, that’s up to you. Don’t bring it around me.”

I didn’t do these things to be a tough guy. But with things like drinking and drugs, you can’t be a fence-sitter around these guys. If you smoke a joint or take a snort the first time—maybe just to show that you’re a regular guy—or if you say, “Maybe later,” it gives the impression that you do drugs. If you’re a fence-sitter, then you’re in a bind. You just invite people to keep offering it to you. And if you say, “Not now,” and then keep refusing and refusing and putting it off, they begin to wonder: What’s up with this guy? But if you draw the line right in the beginning—I don’t do it; I ain’t ever gonna do it—then that’s it, nobody cares anymore.

A lot of people have the misconception that mob guys are all big drinkers or dopers. Some of them are—a greater proportion of young guys do drugs than older guys. But so many guys don’t do anything that you don’t stand out by saying no—it’s no big deal. Tony Mirra killed twenty or thirty people, and he drank only club soda.

The thing is, even though it’s a fake world for you as an undercover agent, it’s a real world for the people that you’re dealing with. And you have to abide by the rules in that world. And those rules include how you establish your own standards, credibility, and individuality. I know one or two guys that drank or did drugs while they were undercover just because they thought they had to do that to blend in or show they were tough guys. It was an enormous mistake. You can’t compromise your own standards and personality. Smart wiseguys will see right through your act. You look like somebody that has no mind of his own, hence no strength.

I don’t use drugs, and I wasn’t going to start using them then just for an undercover role. How could I tell my kids not to use dope if I was out there sniffing coke just for the job?

And there’s another reason, very practical. As an FBI agent, someday down the line I was going to be in court testifying on all these cases we were making. I was not going to lie. And I was not going to tarnish my credibility and risk failing on convictions by taking drugs or getting drunk or doing anything that would suggest I lacked commitment or character.

This line of thinking is not arrived at on the spur of the moment. I didn’t think it over when the guy offered me the coke. I acted spontaneously, because I had sorted all this out in my head and established my priorities and standards before I ever went out on the job.

In any event, I accomplished what I wanted to. While later on I would get involved in drug transactions, nobody ever again offered me drugs for my personal use.

I was down in Miami one time working with Fitz for a week. I had told Jilly and his guys that I would be down there. But I didn’t call them back with a telephone number where I could be reached.

As it turned out, they had tried to find me because they wanted me in on a big job they were going to pull down there.

They had connections in Florida. Guido told me that he had been dealing drugs in Florida for nine years, especially in the Key West area, where he had the fix in with the police department and the district attorney’s office. Vinnie told me that he had a friend who owned a nursery on Staten Island where he was growing a big marijuana crop, and that when it was harvested in August, Guido would take it to Florida for sale.

In this instance they had information about a house in Fort Lauderdale where they could pull off an easy $250,000 cash score. It was a four-man job. When they couldn’t locate me, Jilly joined Guido and Patsy and Frankie. When I got back to New York, they filled me in on what had happened. They had pulled off the job, and it had been a disaster.

The information their Florida tipster gave them was that an elderly lady kept the cash and diamonds in a safe. Guido bought safecracking tools for the job in Miami. They went to the house, flashed their detective shields to the lady, and said they were on an investigation and needed to come in. They handcuffed the lady. But there was no safe. And there was no quarter of a million in cash.

What they found were bullet holes in the ceiling, bank books showing that a huge deposit was made the day before in a safe-deposit box, and a little cash lying around. By the time they accounted for plane fare and tools and other expenses, they came out of the job with about $600 apiece.

Their information had been good, but late. Later their tipster filled in the story. The lady’s husband had died and left the quarter mill. He had promised a large chunk of that to his nephew. But the widow didn’t like the nephew and didn’t want to give him the money. The nephew came to collect. He tried to frighten the lady. He pulled out a gun and fired two bullets into the ceiling. But she didn’t give up the money. The next day she put it all in a safe-deposit box. That was the day before Guido and Jilly went there to steal it.

“If I‘d’ve known all this ahead of time,” Guido told me, “I never would have pulled the job.”

Jilly got 1,200 ladies’ and children’s watches from a job at the airport. He brought samples into the store. As usual, he offered me a piece or all of the load if I could find a market. He gave me a sample to show, a Diantvs.

Meanwhile he had located a potential buyer. A couple of guys were interested in part of the load. The next afternoon, we were in the back room when these two guys walked in.

I recognized one of them as a guy I had arrested two years earlier on a hijacking charge, back before I went undercover and I was on the Truck and Hijack Squad.

I had worked on the street only a couple of months up in New York. So it wasn’t as if I had arrested thousands of people. When you arrest somebody like that, you usually remember him. I remembered the face; I remembered the name: Joe. Just like the crook, he usually remembers the cop that arrests him. It’s just something that stays with you. There we were.

I was introduced. Joe knew the other guys but not me. I watched his face. No reaction. I wasn’t going to excuse myself and leave, because something might click with this guy, and if it did, I wanted to see the reaction so I would know. If I left and something clicked with this guy, I could come back to an ambush. I watched his face, his eyes, his hands.

They talked about the watches, the prices. I decided to get the guy in conversation. Sometimes if a guy’s nervous about you, he can hide it in his expression, just avoid you. I figured if I talked to him, I could get a reaction—either he would talk easy or he would try to avoid conversation with me. I had to be sure, because there was a good chance I would run into this guy again.

“By the way,” I said, “you got any use for men’s digitals?” I had one and showed it to him.

“Looks like a good watch,” he said. “How much?”

“You buy enough, you can have them for twenty each.”

“Let me check it out, get back to you. Where can I reach you?”

“I’m right here every day,” I said.

The conversation was okay. There was no hitch in his reactions. They chatted a few more minutes and left. The whole thing took maybe twenty minutes. The guy simply hadn’t made me. Those situations occur from time to time, and there’s nothing you can do about them, except be on your toes.

A couple days later I asked Jilly, “Joe and that other guy, did they buy the watches?”

He said, “Yeah, they took some of mine, but they didn’t have any market for yours.”

From time to time somebody in Jilly’s crew would ask me if I had any good outlets for marijuana or coke. I was noncommittal. At that time I wasn’t trying to milk the drug side, other than to report back whatever I saw and heard. The FBI wasn’t so much into the drug business then. We didn’t want to get involved in any small drug transactions because we couldn’t get authority to buy drugs without making a bust. We were still operating on a buy-bust standard, meaning that if we made a buy, we had to make a bust, and that would have blown my whole operation. So in order not to complicate the long-range plans for my operation, I pretty much had to steer clear of drug deals.

Guido came up to me at the store. “You got plans for today?” he asked.

“No, I’m just gonna hang out. I got nothing to do,” I said.

“Take a ride with me. I gotta go to Jersey.”

We took Jilly’s car, a blue 1976 Coupe de Ville. We drove across the Verrazano Narrows Bridge to Staten Island. We drove around Staten Island for a while, then recrossed the bridge back to Brooklyn.

I said, “I thought you said you had to go to Jersey?”

“I do,” he said. “I gotta meet a guy.”

We drove up the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway, crossed the Brooklyn Bridge to Manhattan, and headed north on the FDR Drive. Obviously Guido had just been cleaning himself, making sure nobody was following him, with the run to Staten Island. We crossed the George Washington Bridge into Jersey. We took the Palisades Parkway north.

A little after noon we got to Montvale, New Jersey. At the intersection of Summit Avenue and Spring Valley Road, Guido stopped to make a call at a phone booth. He got back in the car and we just sat there.

“We wait,” he said.

About a half hour later a black Oldsmobile pulled up beside us. The driver motioned for us to follow him. We followed him north for a few minutes, across the Jersey line into New York. We pulled into a busy shopping center in Pearl River. Guido and the other driver got out and talked. The other guy was about 6’, 180, with a black mustache. Guido signaled for me to get out of the car.

The guy opened his trunk. There were four plain brown cardboard boxes in there. We transferred the boxes to Guido’s trunk.

Guido asked, “How much is in there?”

“You got ninety-eight pounds,” the guy said. “That’s what you gotta pay me for.”

We got back in the car and headed for Brooklyn.

“Colombian,” Guido said, referring to the marijuana in the trunk. “We should get $275 a pound. On consignment. I got access to another 175 pounds. The guy said he could also supply us with coke, but not on consignment. Money up front for blow.”

I unloaded the boxes and put them in the back of Jilly’s store. The next day when I came in, the boxes were gone. They didn’t keep drugs in the store. Guido handed me a little sample bag. It was uncleaned—stalks, leaves, seeds. “Think you can move some of this?” he said.

“I don’t know,” I said. “I never moved any of this stuff through my people. I’ll ask around.”

I held on to the sample for a couple of days, then gave it back. “Nobody I talked to could use it,” I said.

None of these guys used drugs themselves, so far as I could see. To them it was strictly a matter of business. If these guys had been dopers, it might have been a different story. They really might have tested me. But the fact was that the way you proved yourself with these guys was by making scores, making money.

According to the Mafia mythology, there was supposed to be a code against dealing drugs. In the old days there wasn’t a huge amount of money to be made in drugs, and they didn’t do it. Now that’s where the money is, forget any so-called code. Like anything else with the Mafia, if there’s money to be made, they’re going to do it.

One morning Jilly was sitting at the desk in the back room, scribbling on some papers.

“Gotta fill out these applications,” he said.

The application was for a loan from the Small Business Administration. He told me that they had a guy in the SBA who approved loans. So Jilly would fill out an application with all fake stuff, any kind of junk information: Joe Crap the Ragman, phony business, phony address. Then he’d send it in and this guy would approve it. At that time the SBA was going strong; there was all kinds of money. So if the application looked decent and the amount requested was not so exorbitant as to attract anybody’s attention, they wouldn’t do any big check on it. So Jilly would ask for like $20,000. The guy they owned on the inside would approve it, get the $20,000, take five off the top for himself, and pass on $15,000 to Jilly.

The great thing about it was you didn’t have to pay it back. Since everything on the application was bogus, how would they ever find you? Jilly pulled this off a couple of times.

Another day I got to the club and Jilly wasn’t there. I asked Vinnie, “Where is everybody?”

“Jilly and Guido got a contract,” he said, “and they’re out looking for the guy they gotta hit.”

You don’t ask questions about a hit. If they want you to know, they’ll tell you. But my job was to get information if possible. When Jilly came back, I asked him, “Where were you guys?”

“Me and Guido had to look for somebody,” he said.

“Anything going on?” I asked, as if it might be some kind of score.

He proceeded to talk about an upcoming hijacking. I tried to wrangle the conversation back to the guy they were looking for, but he wouldn’t talk about it. It wasn’t unusual that he wouldn’t tell me. Who was I? At the time I was just a guy who had been hanging around a few months, let alone an FBI agent. You don’t just tell anybody if you have a piece of work to do.

I don’t know if that particular hit came off or not. Whacking somebody is something that you don’t talk about. In my years with the Mafia guys sometimes they would would sit around and discuss how much work they’d done in the past—“work” meaning hits. But ordinarily they never discussed openly any particular individual they hit, or an upcoming one. If something went wrong, they might sit around later and laugh about it.

One time I was hanging out with Lefty Ruggiero at his social club in Little Italy, and he and a bunch of guys were laughing about a job. They had gotten a contract to hit a guy. They tailed this guy for a week, looking for the right opportunity. Then they were told the contract’s off, don’t hit the guy. And it turned out it was the wrong guy they were following. They would have hit the wrong guy. To them it was the funniest thing in the world. “What the fuck you think of that? We’re following the guy for a week and it’s not even the right guy—ha, ha, ha! We’re out every fucking night following this jerk-off. Piece a fucking luck for him, right? Ha, ha, ha!”

On the Fourth of July weekend Jilly had a cookout for everybody. He had a house down at the Jersey Shore, in Seaside Heights, a block from the beach, and he had all the guys down with their wives and girlfriends.

I went to Fretta‘s, the Italian meat market in Little Italy, and bought sausages and cold cuts and cheeses and took it down there for the cookout.

I wasn’t married, of course. Supposedly I had a couple of girlfriends here and there, but I never brought any of them around. The guys used to get on me sometimes about never bringing a girl around, but I told them there wasn’t anybody I cared enough about.

I always wear an Irish Claddagh ring that my wife gave me. It has hands holding a heart, and a crown on it, symbolizing love, friendship, and loyalty. Nobody had ever mentioned the ring.

We were sitting outside at this picnic table, and one of the guys’ girlfriends says, “That’s a nice ring you got on, Don. That’s an Irish Claddagh ring, isn’t it?”

“Yeah.”

“Aren’t those rings for love? Aren’t they used as wedding rings?”

“Yeah, sometimes,” I say. One of the guys asks about it, and I go into the history and so forth.

Then she says, “Well, what are you wearing it for? I didn’t think you were married or anything.”

“No, I’m not. But one of the few girls I was ever in love with gave it to me. Then a couple months later she jilted me. I keep wearing it because I don’t ever want to forget her.”

One of the guys looks puzzled. He says, “You sure you’re not married?”

“Why?”

“Because I just can’t figure it out. You mean, you loved that girl so much that you keep wearing that ring after she jilted you?”

“Sure, why not?”

“I just didn’t think you were the type of guy that could love anybody. You know, the way that you’re here, you’re there, you got no allegiance, no ties to anybody.”

“Well, there always comes a time in somebody’s life when there’s a girl that you love, somebody that’s special, so I’d rather remember it than forget about it. I just want to wear the ring, that’s all. What’s the difference to anybody else?”

The only time I take the ring off is when I work out lifting weights. I wore it during the whole operation. And that was the only time anybody ever mentioned it.

What with hanging out with Jilly’s Colombo crew and with Mirra and Ruggiero’s Bonanno crews and going to Florida to work with Joe Fitz on Sun Apple, I wasn’t getting home much at all. I missed the school sports seasons and watching my daughters cheerlead. I missed two of the girls’ birthdays. I wasn’t home for my birthday, either. I wasn’t home for our sixteenth wedding anniversary—to celebrate, my wife went out with a couple named Howard and Gail who had been close friends of hers for a year before I even met them. I was home maybe two or three nights a month.

And when I was home, I was a little harried, trying to make up for lost family time but unable to put mob business out of my mind completely.

I managed to make it to my younger brother’s wedding. It was a regular big Italian wedding, lots of cash and checks. After the wedding the bride and groom were leaving directly for their honeymoon. They didn’t want to take all this money with them. He asked me to take care of it until they got back. “Who could be safer to leave all this with,” he said, “than my brother the FBI agent?”

I put this big envelope of cash and checks under the front seat of my car and headed back to New York City.

A week later my brother asked me for the envelope. It wasn’t in my apartment. It wasn’t anywhere. It was still under the front seat of my car. I had been all over the place since then, to different neighborhoods in the city. My car had been parked on streets and in garages. I had totally forgotten about the money.

None of my family knew the depth of my involvement. My brother later told me that he began to suspect that I was into something heavy when I forgot about his money. The distractions of my job were causing friction in my family.

The situation was tolerable because it was temporary. A few months undercover. But now we had passed the six-month limit to the operation. I hadn’t reached the big fences. But unexpectedly I was getting deeper into the mob, with my association with Bonanno members Mirra and Ruggiero in Little Italy and their introduction of me to others. My undercover assignment was extended indefinitely.

Physically I was often feeling tired. But the daily challenge stimulated me. I felt good about how things were going.

All this time I was trying to remember everything. Since I didn’t take any notes—didn’t dare to take any notes or write anything down, even in my apartment—I had to remember. Anything of a criminal nature discussed in conversation, any new guy that came through the clubs, the different deals and scores and the different guys involved and amounts of everything—I had to try to remember it all. Eventually federal court cases would depend on the accuracy and credibility of my memory.

It was a matter of concentration. That and little tricks. Like remembering license-plate numbers or serial numbers on weapons in series of threes. The frustration always was that I couldn’t ask a lot of questions, which is one of the things I was trained to do as an FBI agent. A lot of the things I had to remember were things I overheard, and I couldn’t ask for these things to be repeated, or for what I thought I heard to be confirmed. When swag came in and out, I couldn’t ask to look it over more closely, or where it came from, or who it was going to. I had to hope those facts were volunteered. I had to be just a hang-around guy who wasn’t more interested than was good for him.

Concentrating on conversations was draining. Most of the talk was idle, simplistic bullshit about the most mundane things—getting a haircut or a new pair of Bally shoes; how the Mets or Giants were doing; how the Chinese and Puerto Ricans were ruining neighborhoods; how much better a Cadillac was than a Lincoln; how we ought to drop the bomb on Iran; how we ought to burn rapists, each guy would gladly strap the perverts in and pull the switch himself. Most of these guys, after all, were just uneducated guys who grew up in these same neighborhoods.

But they were street-smart, and the thread of the business ran through everything all the time, and the business was stealing and hits and Mafia politics—who was up, who was down, who was gone. Somebody might be talking about a great place to buy steaks at a cut rate and in virtually the same sentence mention a hit, or somebody new getting made, or a politician they had in their pocket. These tidbits would lace conversation continually but unpredictably, and they flew by. If I wasn’t always ready, I would miss something I needed to remember. And I couldn’t stop them and say, “What was that about paying off the police chief somewhere?”

What’s more, to be above suspicion I had to adapt my conversational style to theirs. Occasionally I would change the subject or wander away from the table purposely, right in the middle of a discussion about something criminal that might be of interest to the government—precisely to suggest that I wasn’t particularly interested. Then I would hope the talk would come around that way again or that I could lead it back, get at it later or in another way. It was a necessary gambit for the long term.

And then I would have to remember facts and names and faces and numbers until I could call in a report to my contact agent.

That’s why when I would get home for my one day or evening in two or three weeks, it would be difficult to adjust and focus deserved attention on my family. Especially when they didn’t know what I was doing and we couldn’t talk about it.

One hot August afternoon I was in the store when they came in from a job. Jilly, Guido, Patsy, Frankie, and a couple of other guys, one of them named Sonny. Jilly was nervous as hell. I had never seen him so nervous.

“We hit this house in Bayonne this morning,” he told me. “The guy was a big guy [I wasn’t sure whether he meant physically big or important] and I thought I was gonna have to shoot the motherfucker because he wouldn’t open the safe. I had my gun on him, and I said I was gonna shoot him if he didn’t open it up or if he tried anything. I really thought I was gonna have to shoot him. Finally he opened it and we handcuffed him and the woman and taped his mouth shut.”

He was visibly shaken, and I didn’t know why, because he’d been out on any number of similar jobs.

They had opened a black attaché case on the desk in the back room. Without making a point of sticking my nose into it, I could see jewelry—rings and earrings and neck chains—some U.S. Savings Bonds, plastic bags of coins like from a collection, a bunch of nude photographs of a man, and a man’s wig.

Also in the case were sets of handcuffs of the type you can buy in a police supply house, several New York Police Department badges they probably stole someplace, and four handguns.

“We posed as cops to get in,” Patsy said. “Tell him about the priest.”

Sonny said, “I was in the getaway car across the street from the house, with the motor running. I happened to be in front of a church. I’m sitting there waiting for the guys to come out, and this priest comes walking by. And he stops to chat! ‘Isn’t it a lovely day,’ this priest is saying to me. And he goes on about it. I can’t get rid of him. I don’t know how the guys are gonna come out of the house, running or what, and this priest is telling me about the birds and the sky. I couldn’t leave. Finally he said good-bye and walked away. I could still see him when the guys came out.”

Jilly handed me a small bunch of things. “Get rid of this junk, will you? Toss it in a dumpster in Manhattan when you go back.”

It was stuff from the robbery they didn’t want, and didn’t want found in the neighborhood: a pink purse, a broach and matching earrings, the nude photos, a

U.S. passport.

What I wanted was the guns. They were stolen property that we could trace back to the score and tie Jilly’s crew to it. And we always wanted to get guns off the street.

“If you want to move those guns,” I said to Jilly, “I got a guy that I sold a few guns to from my burglaries, so maybe he’d be interested in these.”

“We should get $300 apiece for them,” he said.

“I’ll see what I can do.”

He gave me the guns: a Smith & Wesson .45; a Smith & Wesson .357 Highway Patrolman; a Rohm .38 Special revolver; a Ruger .22 automatic. Whatever else the owner was, he was not a legitimate guy. Two of the guns had the serial numbers filed off. They were stolen guns before Jilly’s guys got ahold of them. Generally, filing the numbers off doesn’t cause us too much of a problem. Most of the time the thieves don’t file deep enough to remove all evidence from the stamping process. Our laboratory guys can bring the numbers back up with acid.

The next day I put them in a paper bag and walked over to Central Park at Ninetieth St. My contact agent, Steve Bursey, was waiting for me. I handed him the bag. We decided we would try to get by with offering Jilly $800 for the guns. You never give them all that they ask in a deal. First, it’s government money, and we don’t want to throw out more than we have to. Second, you want to let them know that you’re hard-nosed and not a mark.

The next day I went back to the club and told them that my man offered me $800.

“That’s not enough,” Patsy said. “You said you could get twelve hundred bucks.”

“I said I’d try,” I said. “The guy is firm at eight hundred. ”

“No good.”

With some deals I would have just said okay and given the stuff back. But not with the guns. I didn’t want to give the guns back. “Look, I got the guns, I got eight hundred on me. You want it or you don’t.” I tossed the money down on the desk, trusting to their greed when they saw the green. There was some squabbling.

“We could have got more somewhere else,” Patsy said.

“Hey, if you can get more, take the fucking guns and bring them somewhere else. But who’s gonna give you more than two hundred apiece for guns that are probably registered and have been stolen and the numbers filed off? You think I didn’t push for all I could get? There’s eight hundred of my own money. You want the deal, I’ll just collect from him.”

“Okay,” Jilly said. He picked the money up and gave $100 each to Guido, Frankie, and Patsy as their share, and $100 to me for peddling the guns.

I handed in my $100 to Agent Bursey. So the guns cost the FBI $700.

Guido was bitching about a bunch of people that had recently been made in the Colombo family. He mentioned both Allie Boy Persico and Jerry Lang. Allie Boy was Alphonse Persico, the son of Carmine “The Snake” Persico—sometimes referred to as Junior—who was the boss of the Colombo family. Jerry Lang was Gennaro Langella, who some years later would become underboss of the Colombo family and acting boss when Carmine The Snake went to prison.

“I’ve done more work than half the guys that were made,” Guido said, meaning that he had been in on more hits, which is one of the prime considerations in getting made, “and I ain’t got my badge. That kid Allie Boy is just a wiseass punk. He never did a bit of work to earn his badge. The only reason he got made is because his old man is boss.”

“You better shut up,” Jilly said. “People walking in and out of the store all the time, we don’t know who hears what. We’re gonna be history from that kind of talk about the boss’s son.”

I was standing outside Lefty Ruggiero’s social club on Madison Street in Little Italy when Tony Mirra came by and told me to drive him to Brooklyn.

That set off an alarm in my gut. Although it was known that I was moving between crews of two different families, that kind of freewheeling eventually draws suspicion. Pretty soon, if you don’t commit to somebody, they think you can’t be trusted. Suddenly Mirra, a Bonanno guy and a mean bastard, wants me to go with him to Brooklyn where I have been hanging out with Colombo guys. Was he taking me there for some kind of confrontation?

In the car Mirra said he had an appointment with The Snake.