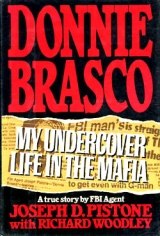

Текст книги "Donnie Brasco: My Undercover Life in the Mafia"

Автор книги: Joseph D. Pistone

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright Page

Dedication

Chapter 1 – THE WHIRLWIND

Chapter 2 – THE BEGINNINGS

Chapter 3 – PREPARATIONS

Chapter 4 – HITTING THE STREET

Chapter 5 – BROOKLYN: THE COLOMBOS

Chapter 6 – THE BONANNOS

Chapter 7 – TONY MIRRA

Chapter 8 – LEFTY

Chapter 9 – MILWAUKEE

Chapter 10 – THE ACCIDENT

Chapter 11 – FRANK BALISTRIERI

Chapter 12 – SONNY BLACK

Chapter 13 – KING’S COURT

Chapter 14 – COLDWATER

Chapter 15 – DRUGS AND GUNS

Chapter 16 – THE RAID

Chapter 17 – THE SITDOWNS

Chapter 18 – THE HITS

Chapter 19 – THE CONTRACT

Chapter 20 – COMING OUT

EPILOGUE

UPDATE

Acknowledgements

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

“Thoroughly absorbing true-life adventure.”

— Newsday

“The tension builds with machine-gun

rapidity ... the suspense of a fictional

mystery yarn but the chilling ring of

reality.... Joseph D. Pistone is a true

American hero!”

— VirginianPilot

“Excellent ... for a view of how the Mafia operates, none can match Joe Pistone!”

— SeattlePost-Intelligencer

“Truly exciting.... so skillfully written it’s worth your time.”

— PalmSprings Desert Sun

“Oozes with names ... and plenty of behind-the-social-club-door gossip.”

— NewYork Daily News

“Unprecedented ... a chilling chronicle of undercover work in the Mafia.”

—UPI

“A penetrating look into the Mafia inner circle ... real-life drama.”

— DetroitNews

“What it’s really like ... fascinating ... frightening ... daring.”

— FortWorth Evening Telegram

“Compelling, gripping, revealing ... raw, hard-hitting nonfiction at its best.”

— TorontoStar

“Immense!y satisfying!”

— OaklandPress

“Chilling ... not since Nicholas Pileggi’s Wiseguy has the day-to-day life of the Mafia been so entertainingly captured.”

— BuffaloNews

“New ground is broken! ... There are few

ways, short of participating in it, that

you’ll get a better look at the business of

crime than by reading Pistone’s

recollections of his life in it.”

— CantonRepository

“An unforgettable eyewitness account!”

— RollaNews

“Fascinating!”

— DaytonNewslJournal Herald

SIGNET

Published by New American Library, a division of

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street,

New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto,

Ontario M4P 2Y3, Canada (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Books Ltd., 80 Strand, London WC2R ORL, England

Penguin Ireland, 25 St. Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2,

Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd.)

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124,

Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty. Ltd.)

Penguin Books India Pvt. Ltd., 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park,

New Delhi – 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0745,

Auckland, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd.)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty.) Ltd., 24 Sturdee Avenue,

Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd., Registered Offices:

80 Strand, London WC2R ORL, England

Published by Signet, an imprint of New American Library, a division of Penguin Group (USA) Inc. Previously published in a Dutton edition.

First Signet Printing, January 1989

Copyright © Joseph D. Pistone, 1987

eISBN : 978-1-101-15406-9

All rights reserved.

REGISTERED TRADEMARK-MARCA REGISTRADA

REGISTERED TRADEMARK-MARCA REGISTRADA

Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

PUBLISHER’S NOTE

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party Web sites or their content.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book via the Internet or via any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal and punishable by law. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the author’s rights is appreciated.

http://us.penguingroup.com

To my wife and children, whom I love dearly.

To both sets of parents, brothers and sisters.

To Michael, Sheila, Janie, Bob F., Howard and Gail,

and Don and Patricia—Thank you.

To the FBI undercover agents, who are the best at

what they do.

To the street agents, who make the FBI the best

investigative agency in the world.

To the U.S. Justice Department Strike Force attorneys

in Tampa, Milwaukee, and especially the Southern

District of New York.

—J.D.P.

1

THE WHIRLWIND

I looked down from the witness stand at five Mafia defendants, five rows of press, and a standing– room-only courtroom filled with more than 300 people. It was an incredible sight to me. This was just the first mob trial, the first group of wiseguy defendants.

Lefty Guns Ruggierro was shaking his head. So were Boobie Cerasani and Nicky Santora and Mr. Fish Rabito and Boots Tomasulo. It was as if these defendants couldn’t believe what was taking place either. Lefty had told his lawyer, “He’ll never go against us.” Up until my appearance on the stand, apparently he refused to believe that I was a special agent of the FBI and not his partner in the Mafia.

But two other defendants had already pleaded guilty before the trial. And later in his jail cell, between court appearances, Lefty had become a believer. He told his cell mate, “I’ll get that motherfucker Donnie if it’s the last thing I do.”

There was a Mafia hit contract out on me. FBI agents were guarding me twenty-four hours a day.

Two days before I took the stand to testify, before my real name was revealed, we got word from an informant in Buffalo, New York, that the mob was going to go after my family.

The chief prosecutor for this case was Assistant U.S. Attorney Barbara Jones. The most powerful Mafia boss, the man who then sat at the head of the Mafia Commission, the boss of bosses, was Big Paul Castellano of the Gambino family. I told Barbara that I wanted to go to Castellano myself and tell him this: “If anybody touches my wife or kids, I will go after you personally. I will kill you myself.” I said I would do that only if it wouldn’t jeopardize the cases. “I can’t tell you who and who not to talk to,” she said.

She was being tolerant and understanding. But I figured it might hurt the cases, so I held off and alerted some people and stayed very watchful.

In the middle of the courtroom, half hidden in the crowd, a Bonanno Mafia family associate I had seen around Little Italy but whose name I didn’t know aimed his hand like a pistol and silently pulled the imaginary trigger with his forefinger. At a break in the trial, agents protecting me got the guy in the hallway and talked to him. He never came back.

I had been undercover inside the Mafia for six years. All that time, no more than a handful of people in the world knew who I was in both real life and in the Mafia. Now there was this explosion in the media.

There were huge headlines in the press, some of them covering the front pages: G-MAN CONNED THE MOB FOR SIX YRS; SECRET AGENT BARES MOB DEALS; MAN WHO CONNED THE MOB; FBI UNCOVERS MOB SUPERAGENT; “BRASCO” FACES GRILLING TODAY. Newsweek had a full page entitled, “I Was a Mobster for the FBI.” They also indicated the threats: MAFIA SEEKS REVENGE ON DARING INFILTRATOR; MOB IS TRACKING FBI-ER WHO FOOLED BONANNO FAMILY.

Before the trial, the media knew that a primary witness would be an FBI undercover agent who had infiltrated the Mafia. They were using every angle to try to find out who it really was. Once the trial began, reporters were always trying to get to me. I had never given an interview, never allowed the press to photograph or film me. We’d finish up in court at five P.M., have to hang around until eight or nine to avoid the press, and even then we’d go out through the marshals’ lockup. We couldn’t go out of the building to eat lunch, or out of the hotel to eat dinner.

Before the first trial began, we had definite word of a hit contract out on my life. The Mafia bosses had offered $500,000 to anybody who could find me and kill me. They had circulated pictures of me all over the country. We thought we’d better take some precautions. The federal prosecutors petitioned the court to allow me and another agent I had worked with during the final year to withhold our real names when testifying and use the undercover names the mob knew us by: Donnie Brasco and Tony Rossi.

Presiding Judge Robert W. Sweet, U.S. District Judge for the Southern District of New York, was sympathetic. In his ruling he wrote, “... there can be no question but that these agents were, are and will be at risk. Certainly their performance as set forth by the government establishes their courage, heroism and skill as front line fighters in the war against crime and entitles them to every appropriate protection [which includes] the withholding of the location of their homes, family situation, and any additional information which is of tangential relevance and might increase their exposure to risk.”

But he denied our motion because of constitutional rights of defendants to confront their accusers. I felt neither betrayed nor surprised. There were never any guarantees.

My real name was not revealed until the first day I testified, when I walked into the courtroom, raised my right hand, and swore to tell the truth. Then I was asked to give my name, and I gave it, for the first time publicly in six years: Joseph D. Pistone.

All those years undercover in the mob, I had been lying every day, living a lie. I was lying for what I believed was a high moral purpose: to help the United States government destroy the Mafia. Nonetheless, I was constantly aware that eventually, on the witness stand, I was going to be confronted with the fact by defense attorneys: You lied all the time then; how can anybody believe you now?

Before, everything, including my life, had been riding on the lie. Now everything was riding on the truth.

When I was undercover, with every step I took I had to think: How will this seem when I testify? I had to be absolutely clean. Money had to be accounted for. I had to document what I could, and remember what I couldn’t document. Finally it would come down to my word in front of the juries.

The two prosecutors in the very first trial, Assistant U.S. Attorneys Jones and Louis Freeh, continually drove the point home to me: “No matter how much evidence we put on, the jury has to believe you. Without your credibility we have nothing.”

From the day I ended my undercover role, July 26, 1981, I was deluged with trial preparations and testimony.

I was in a whirlwind. There was nonstop work with U.S. Attorneys seeking indictments of Mafia members and preparing for trials on racketeering, gambling, extortion, and murder in New York, Milwaukee, Tampa, and Kansas City. I worked with FBI officials at Headquarters in Washington, D.C., to prepare other cases across the nation where my testimony wasn’t needed but my information was. As the weeks and months went by, I was working with the prosecutors, testifying before grand juries, and testifying in trials all at once.

In New York City alone, home of the main Mafia families, there were at times five or six Mafia trials going on at once. Trials coming out of our investigations got famous, such as “The Pizza Connection,” the biggest heroin-smuggling case, and “The Mafia Commission,” the trial of the entire ruling body of the Mafia. Because I had been living within the Mafia for so long, I had information relevant to them all, and I testified at all of them. I would be testifying in more than a dozen trials in a half dozen cities over a span of five years.

Ultimately we would get more than a hundred federal convictions. By 1987, the combination of undercover agents, street agents, cops, U.S. Attorneys, and informants had blasted the heart out of La Cosa Nostra. The Mafia would be changed forever. The boss of every single Mafia family would be indicted and/or in prison and/or dead before the trials were over. We got almost every Mafia soldier we went after.

But the scorecard after all those years wasn’t the scorecard right then. In August 1982, we were just launching the courtroom assault that resulted from the years of undercover work and “straight-up” investigation. There wasn’t the time or inclination to celebrate. We had stung and humiliated the Mafia, but now, because of that, the Mafia was stirred up like a hornets’ nest. The mob was killing its own. Anybody who had trusted me inside the mob was now dead, or targeted for death. A dozen mobsters I knew when I was undercover had been murdered, at least two specifically because of their association with me. One indicted corrupt cop had committed suicide.

For me, there was testifying to do. And I had to avoid the shooters.

In Milwaukee, when I was testifying against Milwaukee Mafia boss Frank Balistrieri, a defense attorney asked me where I and my family actually lived while I was undercover. The prosecution objected. U.S. District Judge Terence T. Evans directed me to answer. Nothing could have forced me to answer that. “Your Honor,” I said, “I am not going to answer the question.” The judge said he could hold me in contempt. But after consultation with the lawyers he decided that what was relevant was only where the mob thought I lived at the time. Then I answered that question: “California.”

My home address and the name my family was living under was a closely guarded secret, and has not been revealed to this day. The FBI installed a special alarm system throughout the house that was wired directly to the FBI office.

Once my real name was splashed around in the media, we got word from a friendly attorney that a New Jersey guy that I grew up with, now in the Genovese family, had gone to Fat Tony Salerno, the boss of the Genovese family, and told him he knew where I was from and where I still had relatives, so maybe they could get at me that way.

When I talked to my daughters by telephone, they were in tears. Grandpa was afraid to go out and start his car in the morning.

The FBI wanted to move my family again. I refused. They didn’t want to move again. I wasn’t going to run the rest of my life. These bastards weren’t going to make me or my family live in fear forever. Could they find me? I take normal precautions. I’m always tail-conscious wherever I am. I travel and have credit cards under various names. But with an all-out effort, sure, they could find me. Nobody’s an impossibility. But if they found me, they would have to deal with me. The guy who came after me would have to be better than I was.

I was forty-three years old when the first of the cases came to trial. I had missed six years of normal life with my family. There were huge gaps of experience with my daughters growing up. I hoped that in time this would be balanced by the pride in what I had done, but I never will be able to be a public person. I will always have to use a different name in my private life, and only close friends and associates will know about my FBI past.

My satisfactions are in the knowledge that I did the best job I could, that we made the cases, and that other agents—my peers—congratulate me and respect me for what I did. My family is proud of me.

I am proud of the fact that I was the same Joe Pistone when I came out as I was before I went undercover. Six years inside the Mafia hadn’t changed me. My personality hadn’t changed. My values hadn’t changed. I wasn’t messed up mentally or physically. I still didn’t drink. I still kept my body in shape. I had the same wife, the same good marriage, the same good kids. I hadn’t had difficulty giving up the Donnie Brasco role. I was not confused about who I was. My pride was that whatever my personality was, whatever my strengths and weaknesses, I was Joe Pistone when I went under, and I was the same Joe Pistone when I came out.

After one trial in New York a defense attorney congratulated me: “You did a hell of a job. You got some set of balls, Agent Pistone.”

At another trial years later, in 1986, Rusty Rastelli, boss of the Bonanno family, which I had infiltrated, waited in a hallway outside the courtroom of the U.S. Court for the Eastern District of New York in Brooklyn. He sat in a chair like a throne, with other defendants, Bonanno wiseguys, gathered around him like an entourage. None of them wanted to believe, or admit, even now, what had been done to them. “Even if I wasn’t in the can,” Rastelli said, “he wouldn‘ta met me.” “He don’t know nobody,” one of his members said, “not in six years.” A daughter of one of the defendants was brought over to meet Rastelli. She said about me, the agent testifying against them all, “What a dangerous job. I wouldn’t want to be in his shoes.”

On January 17, 1983, I went with my wife and brother to Washington, D.C., to attend the annual presentation of the Attorney General’s Awards. Before the ceremonies we had lunch with FBI Director William Webster and his assistant directors in his private dining room in the J. Edgar Hoover Building, which is FBI headquarters.

The ceremonies were held in the Great Hall of the Department of Justice. The room was jammed with dignitaries and government officials.

Among the awards was one for me. Attorney General William French Smith and FBI Director Webster presented me with the Attorney General’s Distinguished Service Award as the outstanding agent in the FBI. They cited my length of service undercover, how no agent had ever penetrated so deep into the Mafia before, and how much personal sacrifice was required. I got a big round of applause.

Next to testifying in my first Mafia trial, this was the best moment in my professional life.

2

THE BEGINNINGS

I was working out of the Alexandria, Virginia, office in my second year on the job. We had been chasing a bank-robbery fugitive for about a month, just missing him several times. I and my partner, Jack O‘Rourke, got a tip that he was going to be at a certain apartment in next-door Washington, D.C., for about a half hour. We alerted the D.C. office so they could send a couple cars, and we took off for the place. When we pulled up, we saw this guy coming down the stairs.

He was a black guy, huge and hard—6’4”, 225. He had pulled off a string of bank jobs and hotel robberies, and had shot a clerk.

This is the middle of a black neighborhood. The guy spots us and takes off through an alley. I jump out of the car and take off after him, while my partner wheels the car around the block to cut him off. We go over fences and down alleys, knocking over garbage cans and making a racket. I don’t draw my gun because he doesn’t show one. Finally, in another alley, I catch up and tackle him. Then we go at each other with fists. Up and down we go, throwing punches. We roll around smacking each other, busting each other up, while a crowd gathers and just watches. I can’t subdue him. I manage to get my cuffs out of the small of my back, put a hand through one, and finally I hit him a good shot that dazes him. That buys me a couple of seconds to get him in a hammerlock and slap one cuff on him.

The other cars arrive, and we subdue him.

We’re walking him to the car and he says to me, “You gotta be a Eye-talian.”

“Yeah?”

“Yeah, ‘cause there’s only two types that fight like that, a nigger or a Eye-talian. And I know you ain’t no nigger.”

It was a sad story. The guy was an ex-Marine with medals for heroism in VietNam. He got discharged and came back and couldn’t get a job. Nobody wanted him as a VietNam vet. He became a heroin addict and a bank robber. About three years after this bust, he got out of prison and went back to the same stuff, and when they were trying to arrest him, he came out shooting, and a buddy of mine had to blow him away with a shotgun.

I felt bad about that guy. But I wasn’t a psychologist or a social worker. I was an FBI agent.

And an Italian. My grandparents came from Italy. I was born in Pennsylvania. I grew up there and then in New Jersey. My father worked in a silk mill and at the same time ran a couple of bars. He retired when he was sixty-two. I have a younger brother and sister.

In high school I played football and basketball, mostly basketball, guard and forward. I was only six feet tall but a leaper, good enough to be second-team AllState. I went to a military school for a year to play more basketball, then went to college on a basketball scholarship. I knew I wasn’t good enough to be a pro. Basketball was just a way for me to go to college. I majored in social studies. I wanted to be a high-school basketball coach. After two years of college I left to get married. I was twenty.

I stayed out a year working, as I had during off times from school, in construction, driving bulldozers, in a silk mill, tending bar, driving tractor-trailers. My wife was a nurse. After a year out, I went back to school to get my college diploma. But I didn’t resume basketball. My wife was pregnant. I had to work full-time. There wasn’t time for basketball. After our first daughter was born, my wife went back to work as a nurse to help put me through college.

Nobody in my family had been a cop. But as a kid I had thought about being a cop or an FBI agent. In my senior year of college a buddy was going to take the exam for the local police department. He wanted me to go in with him. I said I wanted to finish my last year of school. He urged me to take the exam, anyway. I scored in the top five on the written exam, and number one on the physical exam. I told the police chief that I wanted to take the job with the department, but I was in my last semester of college and I wanted to finish and get my diploma. I asked him if it was possible to get an appointment where I would work only the nighttime shift until I graduated. He said he didn’t think there’d be a problem.

But when it came time for the swearing-in, he told me he couldn’t guarantee night shifts for me. So I turned down the job with the police department to finish school.

I got my diploma and taught social studies for a while at a middle school. I liked working with kids. By the time I graduated from college, I had two kids of my own.

I had a friend who was in Naval Intelligence. The Office of Naval Intelligence employed civilians to investigate crimes committed on government installations where Navy and Marine personnel were based, or crimes committed by Navy or Marine personnel in the civilian sector. There were investigations of all types: homicides, gambling, burglaries, drugs, plus national security cases such as espionage.

Often Naval Intelligence agents worked closely with FBI agents. In the back of my mind I had always wanted to be an FBI agent. But you had to have three years of prior experience in law enforcement, along with a college degree.

Naval Intelligence interested me. For that you needed only a college degree. I passed the required exams and became an agent in the Office of Naval Intelligence. I had three daughters by then.

I worked mostly out of Philadelphia. It was basically a suit-and-tie job, normal straight-up investigations, some of the work classified. I worked some drug cases, some theft cases, and so on, and did some intelligence work in espionage cases. I made cases, testified in military courts.

My work there satisfied the FBI’s requirement for prior law-enforcement experience. I passed the written, oral, and physical exams, and on July 7, 1969, was sworn in as a special agent of the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

For fourteen weeks at the FBI Academy in Quantico, Virginia, I was schooled in the law, the violations that come under the FBI’s jurisdiction, and in proper procedures and techniques of interviewing people and conducting all types of investigations. I was trained in self-defense tactics, proper procedures and techniques of car chases and making arrests, and in the use of every type of firearm that the Bureau uses.

In Naval Intelligence I had preferred street work, criminal work, to the intelligence investigations. So when I went into the Bureau, I knew I wanted to do street work. That’s where everybody starts, anyway.

I was assigned to the Jacksonville, Florida, office.

I had been on the job less than a month when I had my first serious confrontation as an agent. We had a warrant for a fugitive, an escapee from a Georgia prison. He was a kidnapper and had shot two people. He had fled across the state line into Florida. My partner got a tip from an informant that this fugitive was going to be in the area, driving a van on the way to some kind of crime job.

We stake out the location with a couple of cars, spot the van going by, and tail it, figuring to move in when he gets to where the job is going down. But after a couple of miles he makes the tail and swerves off the highway and onto side roads to try to shake us. We have to make our move. My partner is driving. He draws up alongside the van and forces it off the road to a stop to our right, my side, so that my door is even with the driver’s door of the van.

The fugitive and I jump out of our cars at the same time, facing each other maybe five feet apart. He has his gun drawn. I’m new on the job. I haven’t pulled my gun. The guy points at me and pulls the trigger. Click. He pulls again. Click. Two incredible misfires.

This all happens in a few seconds. The guy drops the gun and takes off. I’m right on his heels. My partner is out of the car and running after us. “Shoot him!” he hollers to me.

We have strict guidelines on using our firearms. You’re not allowed to fire warning shots. You shoot only to defend yourself; you shoot to kill. But I wasn’t going to shoot this guy. I was burning at myself that I had let this guy get the drop on me. It’s hard running in a suit and tie, but I catch him and clobber him over the head a few times with my handcuffs before I slap the cuffs on his wrists.

My partner comes running up. “Why the hell didn’t you shoot?” he says.

“There wouldn’t have been any satisfaction in that,” I say. The guy had scared me to death. I was angrier at myself than at him, because I hadn’t gotten out of the car with my gun drawn. But by the time the guy panicked and tossed the gun, there wasn’t any reason to shoot him, anyway.

In Jacksonville, I worked fugitive cases, gambling, bank robberies. I started developing informants. I feel that one of my better talents was in cultivating reliable sources from the street world.

I grew up as a street guy. I did not look down at guys who survived by their wits and street smarts, tough guys, thieves. You promise informants that you will protect their relationship with you. You never completely trust them, and they never completely trust you—you’re on the side of law and they’re not.

I didn’t try to rehabilitate anybody. If you become too involved in the social-work aspect, it gets in the way of your investigative abilities.

Some of my first informants were women, because I worked a lot of prostitution cases—cases made federal under the Mann Act, for bringing women across state lines for prostitution. The prostitutes were the victims. We went after the pimps who beat them or burned them with coat hangers for not bringing in enough money or whatever.

Sometimes I would try to talk a prostitute into getting away from her pimp. I didn’t try to talk anybody out of being a prostitute, because that’s just a waste of time. My attitude was: Hey, if that’s the profession you’re going to choose, I’m just giving you some advice on how to survive, that’s all. I got some of them away from their pimps. That made me feel good. And I got some of them to be informants, which made me feel even better.

I had an informant named Brown Sugar. I talked her into at least moving out of the lousy neighborhood into a better, safer area. She didn’t have anything for a decent apartment. I asked my wife if we could give her some of our old pots and pans for her apartment. “I’m not giving my pots and pans to any Brown Sugar,” my wife said. We didn’t have much, either, in those early days of my career, trying to support a family with three kids.

With my partner I did a lot of work in cooperation with the Jacksonville Police Department vice squad. There is a lot of interagency cooperation among guys working the street, because they need each other. Resentment and jealousy between agencies occurs more often at higher levels, where people are looking for publicity.

My partner and I didn’t want publicity because we ended up doing some good but unauthorized work to help out the vice-squad cops. I especially didn’t want publicity because this was my first year as an agent, and in the first year you are on probation; you can be dismissed without cause.

There was a rash of prostitution at the better hotels in the area. High-class hookers were working the bars and lobbies, picking up businessmen.

Everybody in the hotels knew these vice cops because they had been around awhile, but nobody knew me. So to help them out on local cases I would pose as a businessman, get picked up by a hooker and taken up to a room. The local cops would follow us up and wait outside the door for two or three minutes, long enough for the transaction, then they’d come in and make the bust.

I wasn’t a kid—I was thirty—but since I was a new guy on the job, these vice-squad cops liked to have a little fun with me, bust my chops. Like one time I go into the room with this hooker. I give her the money. I wait for them to come through the door. Nothing. She starts undressing. “Come on, honey,” she says, “aren’t you gonna take your clothes off?” I hem and haw. Nothing is happening at the door. She is naked and starts trying to pull off my clothes. I try to push her hands off my buttons and zippers, and I don’t know what to do. My job is on the line here because this is not federal business.