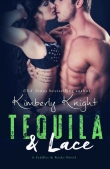

Текст книги "Donnie Brasco: My Undercover Life in the Mafia"

Автор книги: Joseph D. Pistone

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 6 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

One Friday, Jilly was keyed up over a big score he was setting up for the weekend. He had a man inside a trucking company who was going to give him the keys to three trailers loaded with furs and leather jackets. That same inside guy was going to deactivate the Babco alarm systems in the trucks.

Monday morning, Jilly was pissed off with everybody. On Sunday night they had gone into the truck yard. They had opened two of the trailers. When they opened the third, the alarm went off. The whole crew panicked and took off from the scene without grabbing a single item.

It drives the guys crazy to miss a score like that when they were so close, just because somebody fucked up. It also makes them look bad. Jilly had had to get permission to take those loads. On a big score like that, when you’re a low-echelon made guy, a soldier, you have to get permission to make sure you’re not stepping on anybody else’s toes—and also to put the higher-ups on notice that some money will be coming in.

For permission Jilly had gone to his captain, Charlie Moose.

Your captain gets a piece of the action on whatever you do. So you go to him and tell him you’re going to pull a big job. If you don’t tell him ahead of time and he finds out about it, or you tell him after the fact, the captain might start thinking, They got more out of this job than they’re telling me, and that’s why they didn’t ask me up front.

Because that’s what happens all the time. It’s all a big bullshit game. You go to your captain and tell him you’re going to pull off a job worth a hundred grand. Usually the split is half with your captain. So right off the bat you have to give him fifty percent. The captain in turn has to kick in, say, ten percent upstairs, to the boss.

Captains are greedy, just like everybody else. And each captain sets the rules for his crews. He can set any rules he wants. So maybe a captain says, “I want sixty percent, instead of fifty.” Because what he will do is keep fifty and give the other ten percent to the boss. Instead of taking it out of his end, he’s taking it out of yours. Some captains demand that each one of their guys give them a certain amount of money per week, say $200, like a rent payment. That insures they get some money. Plus a percentage of the action.

And that’s because everybody’s playing this same bullshit game, trying to keep as much as they can, pass along as little as they can get away with, regardless of what the rules say. They always fudge. They figure they’re out doing the job, who wants to give up half of what they get to somebody that’s not even there?

So you never told anybody the whole story with money. If you made $100,000 on a score, you might tell your captain you came out with $80,000. That was the standard. It goes that way right up the line. That’s why nobody totally trusts anybody.

Later on, when my position became a connected guy, I had to split whatever I supposedly made on scores with the soldier I was under. He kicked in to his captain. That shows the captain two things: that the soldier is out earning; and that he’s loyal in kicking into the treasury. Same thing with the captains; they keep in good favor by throwing a piece of the action to the boss and the underboss.

Simply put: When you’re operating within the mob, for every score you do, you know that you’re going to split it with somebody at one point or another; you’re going to give some of your earnings up. Everybody plays the game of holding something back. Just so you don’t get caught.

Now, the thing is, it’s a dangerous game, because if you get caught, you’re liable to get whacked—killed. Holding out money from partners, captains, and bosses is, in a business strictly based on greed, a serious offense. If you did get caught, the questions are: How much did you skim and who did you keep it from? Some captains or bosses would have you whacked for withholding $5,000. The thing to remember is, no amount of money is insignificant to these guys. You might get whacked for $200—if it wasn’t your first time skimming, or if other guys needed to be shown a lesson, or if your captain or boss just felt like having you whacked.

So the practice of skimming, from your own family, was common, and so was the result of getting whacked. It would be nothing to have these guys whacked, the guys in Jilly’s crew. They weren’t even heavyweights, just underlings.

So in this case, Jilly and the failed score on the loads of leathers and furs, he had gotten permission from Charlie Moose to take the load, and then he had to go back to Charlie Moose and tell him that the score fell through. Nobody likes to be in a position of having to give his captain such news because, first of all, Charlie Moose would be very disappointed to hear that the money he counted on will not be forthcoming; and second, it would be obvious to Charlie Moose that this crew of Jilly’s fucked up like nitwits.

That was why Jilly was pissed off that particular morning.

Charlie Moose squeezed his crews. That was a subject of common complaint among Jilly’s crew. They’d bitch and moan about Charlie Moose. They’d complain that they couldn’t do anything without his say-so and that he was taking too big a cut of every score. They were all agreed that they’d short him every chance they got.

“What that lousy son of a bitch does,” Guido told me one day at the store, “is whenever anybody in the crew makes a score, you have to take all the money into him, and then he divides it up. He don’t trust us, then we don’t trust him. Fuck him. We pull in a hundred grand, we tell him we got seventy-five. How the fuck’s he gonna know the difference?”

Jilly said, “You better shut up with that stuff. You’ll get us all killed talking like that.”

One way Charlie might know the difference was if somebody there was a snitch, a rat. But that was unlikely. The mentality of these guys is: Once a snitch, always a snitch. So if a snitch rats out these guys to Charlie Moose, even though it might be to the captain’s benefit, Charlie is thinking, “These are the guys he’s with all the time, his own crew, and if he’s willing to rat them out, how do I know that if he gets caught in a box sometime, he’s not gonna snitch to the cops?”

So a snitch would be running at least as much risk as the guy he was ratting on. Nothing is hated more in the mob than a snitch.

While I was not getting to the big fences, I was getting a lot of information. Every few days, or when there was anything significant to report, I passed on the information to my contact agent. Occasionally, when they had pulled a particularly big job, we were tempted to have them busted from the outside. The contact agent and I talked it over. But we couldn’t do that. Since I was the new guy on the block with this Colombo crew, if any busts did go down, the finger would point at me. I’d be the guy that was the snitch. I was caught in the middle. Like everything else I was involved in at this stage, we couldn’t make any busts that might compromise me as a snitch. So a lot of my information just went into the files for later. And later—years later in some cases, because of my continued involvement—the Bureau busted people for some of these scores, or we turned the information over to local police departments for action.

Two guys from Jilly’s crew got out of prison, Frankie and Patsy. And naturally they came back and picked up right where they left off with the gang. They were a couple of tough guys, hard-nosed general-purpose thieves who were used to calling their own shots. And right away they were not too pleased with my presence, because I was new and had worked my way in while they were away in the can.

Frankie was about 5’ 10”, slim and stylish, in his late thirties. If you were casting for the movies, he would be perfect for the classic, shifty-eyed thief. Patsy was maybe ten years older, three inches taller, and ten pounds heavier.

They were big on daytime house burglaries. They would get information on a house where there was cash or jewels or guns. Their gimmick was to pose as detectives to gain entry, then handcuff anyone who was home and ransack the place. They had regular detective shields they could show, and they always had a guy in a getaway car outside.

They decided that a couple of houses in Hicksville, Long Island, were great prospects for burglaries. They went out there and posed as morning joggers to trot by and case the places. They would park their car down the road a ways and jog by the houses in their sweat suits.

The morning they were to hit this one house, they drove up and discovered there were a whole bunch of cars parked in the driveway. They canceled the job.

They jogged past the second house to case it. When they jogged back to their car, they saw a woman writing down their license-plate number. They canceled that job.

Jilly and Frankie and I went out in Jilly’s car to case a job in Hicksville. They had information that the owner of the house, supposedly the head of some retail dry-cleaners’ association, had a bed built over a safe in which there was a lot of cash. Apparently our car was noticed as being strange to the neighborhood and suspicious, because somebody called the cops. The cops came by, stopped, and talked to us. They asked us what we were doing. We said we were just looking for potential properties to buy. On the car seat was a black attaché case in which were two revolvers, one a .38 and one a .32; some loose bullets; and several sets of handcuffs. The cops were satisfied with our explanation. But that blew that job.

By now I was used to putting my two cents’ worth in on plans for scores, while still trying to avoid participating. It was part of my function to discourage them from pulling jobs, especially those where somebody might be in the house or somebody might get hurt. So when I had a chance, that’s what I did. Anyway, at the same time I was gathering a lot of information on criminal activity, which was also my job.

They had cased a job in Mountainside, New Jersey, and they wanted me to take a run over there and check out the alarm system, see if they could get by it. Since I was a burglar and a jewel thief, I had to know about alarm systems.

So I went over to this house. It was a mansion surrounded by a big fence. It looked like it would be a good house to hit. Of course, I didn’t check out the alarm system. I didn’t go anywhere near it.

But I went back to Jilly’s and told them it looked like the place had a very complicated alarm system that I didn’t know how to bypass, plus probably a secondary backup system that I couldn’t observe. Plus, it looked to me like there wasn’t a good escape route for getting out of the place in case the alarm was tripped. My recommendation was that they forget about that job.

Patsy really wanted to pull that job. He was pissed because I was trying to squelch it.

“It’s not worth a shot at getting caught,” I said.

“You just don’t want to come with us on this,” he said. “You’re fucking afraid.”

“You’re right, I don‘t,” he said. “If I can’t get by that alarm, what am I gonna do? Break a window and go in like some fucking two-bit junkie? But you guys can go ahead and do it, just count me out.”

Then the other guys decided they didn’t want to do it, either.

Their next house job they pulled off without telling me about it—some wealthy woman’s house over in Jersey someplace. When I came into the club the next morning. Patsy was parading around showing off this huge diamond he was so proud of. Everybody was oohing and aahing because of how much money it would bring. It was three carats, Patsy said.

He got around to me. I took the diamond and looked it over. “I wouldn’t get too excited about it,” I said, “because this is fake, a fugazy.”

“What the hell are you talking about?” Patsy said, grabbing the stone.

“It’s a zircon, is what I’m saying.”

Patsy snapped his head back like I had shoved a stick up his nose. “You’re full of shit,” he said. “That broad wouldn’t have no fugazy diamonds in her house. We had information the broad didn’t have no fake jewelry. It’s three fucking carats!”

“It’s a fugazy,” I said. “Take it home for your kid to play with.”

“You’re such a smartass, like you know everything.”

“Hey, Patsy,” I said, “you just got out of the can, and I never been in jail, so I must be just a little smarter than you. You want to embarrass yourself, pal, take that stone to your fence, the jeweler you talk about.”

“That’s exactly what I’m gonna do,” he said. He stomped out with the gem. I could have been wrong, of course, and at least my credibility would have been hurt. But I had taken that gemology course, and I wanted to demonstrate that I knew something about gems. The stone was just too big—nobody would have this big a stone lying around in their house. And the color was a little off. I just had a gut feeling about it.

Half an hour later Patsy was back, his tail between his legs. He wouldn’t look at me. “How’d you know?” he said.

“I’m a jewel thief all my life, so I shouldn’t know about diamonds? You oughta stick to hijacking coffee and sugar, because that’s what you know.”

“Gettin’ on my nerves,” he muttered.

“Hey, I was trying to do you a favor. You’re supposed to know this shit. You take it to the guy and he tells you it’s a fugazy, what’s he gonna think of you next time you come in with a stone?”

“Your fucking time will come when you won’t be such a smartass,” he said.

A couple days later I came in and they were planning a burglary of a clothing factory nearby in Brooklyn. The job was to involve me and six other guys, including Frankie and Patsy.

This was a small place that made sport clothes, jeans, blouses. They had been discussing this idea for days, and I had stayed out of it. Now they had it finalized.

I sat down at the table and said, “How we going about doing it?”

It was a beaut. Supposedly there were about twenty or twenty-five people working at this place, most of them women, most of them Italian. Quitting time was five P.M., so at around four-thirty, when most of the salesmen would be gone and just employees left in the place, they’d back a forty-foot trailer truck up to the loading dock. The crew would go in, announce a stickup, handcuff everybody, and load up the trailer.

I had to try to talk them out of it. First, with all this handcuffing and so on, somebody was going to get hurt. Second, because of that first reason, there was no way I could go along on the job, and when the shit hit the fan and the operation got busted up—which in all likelihood would happen—I didn’t want the fingers pointing at me as the snitch.

“Well, it sounds good,” I said. “But how long is it going to take to load up the trailer and get out of there?”

Two hours, was the answer.

“Wait a minute,” I said. “Quitting time is five o‘clock. What happens when the husbands and boyfriends of the women who work there come to pick them up? They just gonna sit and wait in the car for a couple hours without checking inside, while their wives are inside handcuffed and you load your truck? Or if a husband is home at five-fifteen and his dinner isn’t on the table by five-thirty-his wife isn’t even home—what’s the first thing he’s gonna think? That she’s out screwing somebody. What’s the first thing he’s gonna do? He’s coming to this factory and backtrack to find his wife. They’re all gonna come right down to the factory. It’s gonna be like a zoo. You’re gonna have a hundred fucking people coming down there while you’re loading the trailer. What are you gonna do, barricade the fucking doors while you load the trailer and everybody’s handcuffed inside? I think it’s a pretty stupid idea.” “

Patsy started fuming. “Every time we plan to pull a fucking score, you got something to say, throw a monkey wrench in. We think this is a pretty good fucking idea.”

“You’ll be back in the can,” I said, “thinking up such good ideas. But you do whatever you want. I don’t have to be in on it. I’m just trying to save your ass. But I ain’t the boss.”

Jilly said, “I don’t think it’s good. That joint is only half a mile from here. Too close. Not good.”

Jilly was the boss. So that blew off that plan. But there was a lot of heat in that room.

6

THE BONANNOS

One morning not long afterward, I walked into the store. Everybody was there, but nobody was saying much. Jilly took my elbow and said, “Don, let’s take a walk.”

We went outside. He said, “Look, Don, nothing for nothing, but Patsy and Frankie, they don’t feel comfortable around you. They got a beef.”

“What’s the problem?”

“They feel like they don’t know you well enough. They don’t want you involved in any more jobs until they know more about you. They want the name of somebody that can vouch for you down in Miami where you said you did a lot of work, so they can feel more comfortable with you.”

“Well, how do you feel, Jilly?” I said. “We’ve done stuff together, right? You know who I am. You got any problems with me?”

“No, I got no problems with you.” Jilly was uncomfortable. “But I grew up with these guys, you know? They been my partners for years, since before they went to the can. So they got this little beef, and I gotta go along with them. Okay?”

“Fuck them, Jilly. I’m not giving them the name of anybody.”

“Let’s just take it easy, okay, Don? Let’s go in and talk it over, try to work it out.”

Jilly was the made guy, the boss of this crew. I had rubbed these other guys the wrong way, and they had gone first to Jilly and put the beef in with him, which was the right way to do it. He had to respect their wishes because of the proper order—he had known them longer than he knew me, even though he had faith and trust in me. It was their beef, but it was his responsibility to get it resolved one way or the other. He was handling it the proper way. He came to me and talked to me first.

Then, when I hard-nosed it, said no right up front (I couldn’t give in right away, I had to string it out and play the game), he said we had to sit down and talk about it. When you sit down, everybody puts their cards on the table and airs their beefs out. And Jilly had to lean toward them in granting their request about getting somebody to vouch for me in Florida. At that point I wasn’t worried; because things were being handled in the right way, according to the rules.

We went back in the store. I went over to Patsy and said, “You got a beef?”

“You say you pulled off all those scores down in Miami before you came here,” Patsy said. “But we don’t know nothing about that. And you seem to want to say a lot around here. So Frankie and me wanna know somebody you did those jobs with, so we can check you out.”

“You don’t need to check me out,” I said. “I been around here five-six months. Jilly and the other guys are satisfied. I don’t have to satisfy you just because you were in the can.”

“Yeah, you do,” he said. “Let’s go in the back and sit down.”

Everybody walked into the back room. Patsy sat down behind the desk. “You could be anybody or anything,” he said. “Maybe you’re a stoolie. So we want to check you out, and we need the name of somebody to vouch for you.”

“I’m not giving you any name.”

Patsy opened a desk drawer and took out a .32 automatic and laid it on the desk in front of him. “You don’t leave here until you give me a name.”

“I’m not giving up the name of somebody just to satisfy your curiosity,” I said. “You don’t know me? I don’t know you. How do I know you’re not a stoolie?”

“You got a fucking smart mouth. You don’t give me a name, the only way you leave here is rolled up in a rug,” he said.

“You do what you gotta do, because I ain’t giving you a name.”

It was getting pretty tense in there. Jilly tried to be a mediator. “Don, it’s no big deal. Just let him contact somebody. Then everybody feels better and we forget about it.”

I knew all along, from the time he pushed it to the gun, that I would give him a name. Because once he went that far in front of everybody, he wouldn’t back off. But even among fellow crooks you don’t ever give up a source or contact easily. You have to show them that you’re a stand-up guy, that you’re careful and tough in protecting people you’ve done jobs with. So I was making it difficult for them. I acted as if I were really torn, mulling it over.

Then I said, “Okay, as a favor to Jilly, I’m gonna give you a name. You can check with this guy. But if anything happens to this guy, I’m gonna hold you responsible. I’ll come after you.”

I gave him the name of a guy in Miami.

He said, “Everybody sit tight. I’m gonna go and see if we can contact somebody down there that knows this guy of yours.” He left the room and shut the door.

I was nervous about the name I gave him. It was the name of an informant, a thief in Miami who was an informant for another agent down there. It had been part of my setup when I was going undercover. I had told this other agent to tell his informant than if anybody ever asked about Don Brasco, the informant should say that he and Brasco had done some scores together, and that Brasco was a good guy. The informant didn’t even know who Don Brasco was, just that he should vouch for him if the circumstance came up.

So now I had a couple of worries. That had been seven months before. I wasn’t absolutely sure that the informant got the message, and if he had been told, would he remember now, seven months later? If the informant blew it now, I was going to get whacked, no doubt about it. The other guys in the crew here didn’t care; they were on the fence. But Patsy or his pal Frankie would kill me, both because of the animosity between us and because they had taken it too far to back down.

While Patsy was gone, I just sat around with the other guys playing gin and bullshitting as if everything were normal. Nobody mentioned the problem. But I was thinking hard about how the hell I was going to get out of there at least to make a phone call.

After a couple of hours I figured everybody had relaxed, so I said, “I’m gonna go out and get some coffee and rolls. I’ll take orders for anybody.”

“You ain’t going anywhere,” Frankie says, “until Patsy comes back.”

“What are we here, children?” I say. “I got no reason to take off. But it’s lunchtime.”

“Sit down,” Frankie says.

If it came to it, I would have to bust out of there somehow, because I was not just going to sit there and take a bullet behind my ear. There was a door out to the front, which I figured Patsy had locked when he went out. There was a back door, which was nailed shut, never used. And there were four windows, all barred. I didn’t have many options. I could make a move for the gun on the desk; that was about it. But I wouldn’t do anything until Patsy came back with whatever the word was, because I might luck out. And if I could stick with it and be lucky, I would be in that much more solid with the Colombo crew.

We sat there for hours. Everybody but me was smoking. We all sat and breathed that crap, played cards, and bullshitted.

It was maybe four-thirty when Patsy came back. Instantly I could see I was okay—he had a look on his face that said I had beaten him again.

He said, “Okay, we got an answer, and your guy okayed you.”

Everybody relaxed. Everybody but me. With what had gone down, I couldn’t let that be the end of it. You can’t go through all that and then just say, “I’m glad you found out I’m okay, and thank you very much.” The language of the street is strength; that’s all they understand. I had been called. I had to save some face, show everybody they couldn’t mess with me. I had to clear the air. I had to smack somebody.

The gun was still lying there. But now we were all standing up, starting to move around and relax. I wanted to take Patsy first. But Frankie was the one between me and the gun. I circled around, casually edging over to him. I slugged him and he went down. Patsy jumped on me and I belted him a few times. Then the rest of the crew jumped in and wrestled us apart. I had counted on the crew breaking it up before it got out of hand, so I could make my point before the two of them got at me at once.

Patsy was sitting on the floor, staring up at me.

“You fucking punks,” I said. “Next time you see me, you better walk the other way.”

Guido, the toughest of all of them, stepped in front of me and looked at everybody else. “That’s the end of it about Don,” he said. “I don’t want to hear nothing else from nobody about Don not being okay.”

Sally’s club was a place where everybody tended to let their hair down during the long Tuesday lunches. They would bullshit about scores, about guys they had beefs with, about things that got fucked up. They would like to laugh and break each other’s chops.

The next lunch at Sally‘s, the matter of the fugazy diamonds was good for ball busting. They called me “Don the jeweler” and said I probably thought all diamonds were fake. They got on Patsy for getting so high on a fake diamond. “Patsy’s gonna get some real diamonds someday,” somebody said. “But he can’t show them to Don, because Don’ll say they’re fake and Patsy won’t know the difference.” Everybody laughed.

Patsy and Frankie didn’t mess with me after that, even though we continued to be involved with each other. They treated me with some respect. Later on, ironically, Patsy turned informant and was put in the federal Witness Protection Program.

I had met Anthony Mirra in March of 1977. He invited me downtown to Little Italy. He had a little food joint called the Bus Stop Luncheonette at 115 Madison Street. We used to hang out there, or across the street at a dive called the Holiday Bar.

Mirra also introduced me to Benjamin “Lefty Guns” Ruggiero, like himself a soldier in the Bonnano family. Like Mirra, Lefty was known as a hit man. He had a social club at 43 Madison Street, just up the street from Mirra’s Bus Stop Luncheonette. Mirra used to hang out there. He introduced me to Lefty on the sidewalk outside the club. “Don, this is Lefty, a friend of mine. Lefty, Don.”

Lefty was in his early fifties, about my height—six feet—lean, and slightly stoop-shouldered. He had a narrow face and intense eyes.

Mirra turned away to talk to somebody else. Lefty eyed me. “Where you from?”

He had a cigarette-raspy voice, hyper. “California,” I said. “Spent a lot of time between there and Miami. Now I’m living up at Ninety-first and Third.”

“How long you known Tony?”

“Couple months. Mainly the last few months I’ve been hanging out in Brooklyn, 15th Avenue. With a guy named Jilly.”

“I know Jilly,” Lefty said.

Prior to that introduction, I was never invited into Lefty’s club, and you can’t go in without permission when you’re not connected. From that time on, I would go down to Lefty’s almost every day to meet Mirra. So I got to know Lefty.

I then began dividing my time between Mirra, Lefty, and the Bonanno guys in Little Italy, and Jilly and the Colombos in Brooklyn. Since I wasn’t officially connected to anybody, it was permissible, if not encouraged, to move between two groups. But it was also a lot to handle when you’re trying to stay sharp on every detail.

My time became triply divided with Sun Apple. The “Sun” part of Sun Apple was not proceeding as well as the “Apple” part. Agent Joe Fitzgerald had set himself up with an identity, an apartment, and the rest, just as I had, and we did basically the same thing. Fitz was doing a good job working the street in the Miami area, and he fingered a lot of fugitives for arrest. But for whatever reasons, the operation there didn’t catch on as readily. Most of the guys Fitz was able to get involved with were guys that were chased out of New York, small-time dopers, credit-card scammers, and the like. No real heavyweights.

Now that I had some credentials with both the Colombo and Bonanno people, we thought that maybe I could help stimulate some contacts in Miami. So from time to time I would go down there and hang out with Fitz, letting people know that I was “connected around Madison Street” and in Brooklyn.

I had a dual role, hanging out with Fitz. First was to help him if I could, by being a connected guy from New York who he could point to for credibility. Second was to build up my own credentials. I would tell people in New York that I was going down to Miami to pull some sort of job. I would be seen down there hanging out in the right places. Word always gets back. So you always had to stay in character.

One time we were at an after-hours joint named Sammy‘s, where a lot of wiseguys hung out. We were at the bar. Fitz was talking to a couple of women to his right. I was sitting on his left, at the L of the bar, and around the corner of the L were three guys talking together. One of them was drunk, and I recognized him as a half-ass wiseguy from New York.

This drunk starts hollering at me. “Hey, you! Hey, you, I know you.”

I ignore him, and he reaches over and grabs my arm. “Hey, I’m talking to you!” he says. “I know you from somewhere. Who you with?”

“I’m with him,” I say, pointing to Fitz.

Not only is he drunk, but he is also saying things he shouldn’t be saying around wiseguys, asking things he shouldn’t be asking—such as about what family I was with. I signal to the two guys with him. “Your friend is letting the booze talk,” I say. “He’s out of line, so I suggest you quiet him down.” They shrug.

I call the bartender over. “I want you to know that this guy is out of line here,” I say. “And you’re a witness to what he’s saying, if anything happens.”

The drunk keeps it up. “I know you from New York. Don’t turn away from me. Who you with?”

I lean over to Fitz. “He grabs me again, I’m gonna have to clock him,” I say.

“No problem,” Fitz says. He is standing there, all 6’5” of him. “When you’re ready, let me know, I’ll take care of those other two guys.”

The drunk grabs me by the shoulder. “Hey! I’m talking to you!”

“Okay, Fitz,” I say. I reach over and belt the drunk, and he slides off the stool. At the same time Fitz clocks the second guy, and then the third guy, one right after the other. All three of them sink to the floor.