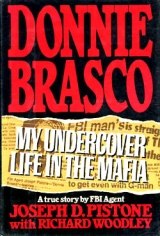

Текст книги "Donnie Brasco: My Undercover Life in the Mafia"

Автор книги: Joseph D. Pistone

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 16 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

I left Milwaukee. I still had to face the music back in New York. I still didn’t know what had spooked Frank Balistrieri. But if we had covered our tracks as well as I thought, I might get punished, but I wouldn’t get whacked.

12

SONNY BLACK

I wasn’t punished. I wasn’t put on probation. Mike Sabella gave me the cold shoulder, but since I wasn’t a made guy, I was excused for a couple of errors in judgment. Lefty never let me forget how I let Conte and $200,000 get away. For a few months I moved around the country, ostensibly checking out scores for Lefty and me.

I was in Miami in July when Lefty called and told me to go out and buy the New York papers. “You’ll be in for a big surprise,” he said.

Carmine Galante had been hit. The Bonanno family boss had been out of Atlanta federal prison for only a few months. When I used to stand guard for him with Lefty outside CaSa Bella, I worried about getting whacked. Now there was Galante himself on the front page, lying dead on his back in a pool of blood, his cigar still clenched between .his teeth. He had been shotgunned to death by three men while having lunch in the rear courtyard of Joe and Mary’s Italian American Restaurant on Knickerbocker Avenue—the street where the zips hung out—in the Bushwick section of Brooklyn. The restaurant owner and a friend were also killed. Two other guys were identified as having been with Galante at the lunch: Galante’s bodyguards, Baldo Amato and Caesar Bonventre, two of the “zips” I had seen around the Toyland Social Club. They had fled after the shooting.

I called Lefty. “Wow,” I said.

“There’s gonna be big changes.”

“Well, where do we stand with everybody?”

“I can’t talk over the phone. Come in right away.”

When a boss gets killed, that’s not the end of it. If one faction got permission from the Commission to take out a boss, rival factions, or those loyal to the dead boss, must be brought into line or wiped out. There will be a winning side and a losing side. Sometimes it takes years before one side wins and the killing stops. I didn’t know how the factions lined up and which side Lefty would end up with now. Lefty had hated Galante, but you couldn’t go just by that. Supposedly the zips were Galante’s chosen people. But two of his prime zips were with him when he got whacked, and that said setup. So I didn’t know where anybody stood, which means I didn’t know where I stood, either.

I met Lefty on Madison Street, outside the candy store.

“Rusty Rastelli is the new boss,” Lefty says, “even though he’s still in the can. We’re gonna be under Sonny Black. He was made captain. He’s taking over Mike’s crew.”

Dominick “Sonny Black” Napolitano was with the Brooklyn Bonanno crew. I had seen him around once or twice, but for the most part the Brooklyn guys hang out in Brooklyn, the Manhattan crew in Manhattan. Sonny had been in prison for hijacking most of the time I had been on this job.

“What about Mike?” I ask.

“Him and Nicky were both supposed to get whacked, but they got passes because a lot of people liked them. They made a deal to get knocked down instead.”

Sabella and Marangello accepted demotion. Now they were just ordinary soldiers of Lefty’s rank. They were lucky.

“So where does all this leave us?” I say.

“We got no problems. I thought I was gonna get whacked.”

After Galante got hit, he said, he got a call from Sonny Black. Sonny, even though knowing that Lefty was under Mike Sabella, directed him to come to a midnight meeting at the Motion Lounge, Sonny’s hangout at Graham and Withers Streets in Brooklyn. And Lefty wasn’t to tell anybody where he was going.

“I figure they’re gonna whack me, too, because I was always close to Mike,” Lefty tells me. “And he’s telling me I can’t tell my own captain I’m going over there. But I got no choice because I know that Sonny Black is now a power. I don’t know what the fuck’s coming down when I drive out to Brooklyn to see Sonny.”

The meeting was friendly. Sonny told him all that had happened—who’d been knocked down, who the new captains were, and so forth. Joey Massino, the fat guy I had seen hanging around social clubs, was made captain. Sal Catalano, another Toyland guy, was made street boss of the zips, the imported Sicilians. And Caesar Bonventre, the slick young zip who was with Galante when he got whacked, was made captain—at twenty-eight, the youngest in the family. Sonny gave Lefty a choice to go with him or with Joey Massino. But Sonny wanted him.

“So I says, ‘Yeah, I’ll be with you.’ ”

In mob business you ask questions about aspects that pertain only to you. Normal curiosity is not normal curiosity for a wiseguy. A wiseguy does not go around asking who clipped the boss. Look too curious and you draw attention to yourself. If the cops did break something, the first thing everybody thinks is that there was an informant. I didn’t want anybody saying, “Why was Donnie so curious about everything?”

I didn’t go out of my way to learn what intelligence the FBI might have been getting about the murder from informants. I didn’t want to know more than I could logically know as a connected guy. It could be just as risky to know too much as to know too little. I didn’t want the burden of having to sort out what I should know from what I shouldn’t.

The murder of a boss doesn’t get talked about much on the street. Business policy doesn’t change. There’s only one policy in the mob: You earn money and you kick your money upstairs. Only the personalities change, and ordinary wiseguys or connected guys don’t have anything to say about that. You go about your business while the power is sorted out by leaders of the factions.

“When Rusty gets out of the can,” Lefty said, “things are gonna be different.”

He liked Philip “Rusty” Rastelli. They were old buddies. I had never seen Rastelli because he had been in the can since 1975 for extortion.

It was strange walking down Mulberry Street past CaSa Bella and realizing that Mike Sabella was no longer a power.

For a time, Lefty said, nobody would be making any big moves. He was back to his check scams and numbers rackets. He decided that our fish-and-chips place would become a fast-food fried-chicken takeout place instead and, with his daughter running it, would be a steady source of income from the projects nearby. He wanted to buy the bar on the corner, but for that we would have had to come up with $60,000, and there was no way the Bureau wanted to get into that kind of money, and no way I wanted to be tied down running a bar.

Meanwhile I had some freedom to move around and contribute to other operations. Other agents could introduce me as a connected guy and a friend of theirs from New York, and that would enhance their credibility with the badguys they were working on. I told Lefty I had to start making some bigger money, so I wanted to check out a few things here and there. I worked short stints on various Bureau undercover investigations, ranging from New England to the South-west. Some of these operations are continuing, some came to nothing. Some I can’t talk about.

Larry Keaton, the agent working out of L.A., had an operation going on in a suburban town involving a gang of blacks engaged in political corruption, gambling, and drug dealing. He wanted to show these guys that he had mob connections. He wanted me to come out to Las Vegas and pose as a Mafia member representing a boss. He had another guy lined up to play the part of the boss.

My supposed role was to see if these guys had projects worthy of putting before the boss. And if they did, I was to prepare them for meeting the boss, tell them how to act.

I went out to the Desert Inn where we had a big suite. These four guys arrived, tough, slick-looking dudes dressed in the latest outfits. We arranged the guys around the room and I told them how to sit. One guy put his feet up on the coffee table and I kicked them off. “You think you can talk to a boss with your feet up that way?” I say. “You got no respect for furniture?” I tell another guy, “Don’t slouch on the sofa that way! Sit up and look like you’re interested in meeting a boss.”

“See,” Larry says, “this guy ain’t fucking around. You misbehave in front of the boss when he comes in, you’re gonna get me in a jam. Because everything here is a reflection on me.”

Everybody now is sitting up straight and tall and paying attention. I go at them one at a time. “You, what’s your name again? What’s your gig?” They tell me they move some coke, some marijuana, run a gambling place. I say, “We have to be assured that you guys can guarantee protection with the local politicians and sheriffs.” I start to draw them out on what they can do, because I have to justify taking the boss’s time. They say, “We got some politicians in town, the sheriff.” They really want to convince me they are worthy of meeting the boss. They give me names, dates, amounts, plans.

“Hey! Slow down,” I say. “When the boss comes in, you have to talk slow, make everything clear, because he doesn’t want to have to ask for anything to be repeated, and he’s not used to talking to blacks or hearing black street talk.”

Also, we had the room bugged and wanted to make sure we got everything.

I said that when he comes in here, they should show respect, stand up. They should not expect to shake hands. Nobody touches the boss. They shouldn’t speak unless they’re asked to speak. They shouldn’t expect the boss to speak to them because the boss doesn’t speak directly to ordinary citizens. The boss is only coming here as a favor to Larry because he thinks a lot of him. We got everybody all tensed up, concentrating on doing everything right, sitting straight, talking slowly and clearly.

Then I went into the next room to get the boss.

The boss, an agent going by the name of Steve, was perfect. He was dressed up in a black suit with a white tie and a white carnation in his lapel. Stocky guy, dark face, heavy five-o‘clock shadow. He looked like Frank Nitty from the old Untouchables TV show.

I make a big production of bringing him in, pulling out a chair for him to sit down.

“Okay, Donald,” the boss says, “introduce me to the gentlemen.”

One by one I introduce them. I say that I told the boss the whole thing, and he’s very pleased that you guys are dedicated in this, and capable of making the scores, because he thinks a lot of Larry. He doesn’t want to put Larry in any position that’s going to be adverse for him.

Oh, no, they say, we wouldn’t do that.

Steve the boss doesn’t say a word. He just nods. I ask if they have any questions they want to ask the boss. No, no, no. Then I say to Steve, “Boss, anything you want to say to these gentlemen?”

He says, “Just tell them that I’m glad everything’s going to work out.”

I repeat his words, then say, “Okay, that’s it.” And I walk the boss out.

The whole thing took maybe forty minutes.

I didn’t have anything more to do with that case. Larry got them all convicted.

Lefty and I spent a lot of time around Miami—vacationing, losing money at Hialeah or the dog tracks, looking for deals. Miami was considered more or less open territory, like Las Vegas, where the different mob families could operate so long as nobody stepped on anybody else’s toes. Lefty was always scheming about how to crack into Florida where the big money was. He was always on the lookout for a bar or lounge to buy, once we made a big score and had some cash. “That’s how you make a fortune,” he would say, “grab yourself a good lounge.”

We would often stay at the Deauville or the Thunderbird where a lot of the wiseguys that he knew stayed. He introduced me to wiseguys here and there, including some Bonanno guys that lived in the area. The Deauville was a favorite of Lefty’s because the manager, a straight guy named Nick, was a friend of his. Lefty always talked to him about getting a lounge or a game room going in one of the hotels, and Nick was always keeping his eye open.

Lefty and I were in Miami in August when a bunch of guys came down from New York for a vacation with their wives or girlfriends. They kept talking about how nice it would be to have a boat and go for a sea cruise. Lefty, who missed having a boat of his own, was always yearning to get on the water.

This was during the time that the undercover sting operation that became known as ABSCAM was under way. Eventually several Congressmen would be caught taking bribes from agents posing as rich Arabs. For the operation the FBI was using a boat to entertain their targets. Called the Left Hand, it was a white Chinese-made yacht, one of only two or three such models in the world. It had a full-time captain on board.

I happened to know the agent working ABSCAM. His undercover name was Tony Devita. I got in touch with him and explained what I had—a bunch of wiseguys and their ladies who would be very impressed if I could take them out on that boat. I asked him if ABSCAM was going to break anytime soon, and if not, if the boat could be available. He assured me that nothing would break publicly on the case for a long time. He found an open date in the schedule and set it up for us to use the Left Hand.

I told the guys that a girl I had been fooling around with up in Fort Lauderdale had introduced me to her rich brother, who owned a fancy boat. The brother was living in California but kept the boat at Pier 66 in Fort Lauderdale. She introduced me to her brother when he was visiting, and we hit it off. He put me in touch with the captain and said if I ever wanted to use the boat, I was welcome. So I had reserved the boat for a day.

Everybody was excited. There were about a dozen of us, including Lefty and one of the bartenders from 116, the Holiday Bar. We went out and bought Italian cold cuts and bread and olives and pickles and side dishes. The women made up sandwiches. We stuffed coolers full of beer and wine and sodas. We piled into our cars and headed up to Pier 66.

They went nuts when they saw the boat—especially Lefty, because he was proud of how his partner could produce for the crew. “What a fucking boat!” he says. “Donnie, you did some fucking job getting a boat like this.” Everybody was oohing and aahing as we went on board.

“Where’s your broad?” Lefty asks me. “The one with the brother?”

“She couldn’t make it.”

I did, however, bring along another guy. As a favor to another agent running another operation, I introduced an undercover policeman into my Mafia crowd. The cop’s undercover name was Rocky. Bringing Rocky along on the cruise helped establish him with some of the badguys he might be running across in his operation.

Out on the ocean we went. We cruised around all day, ate and drank and had a wonderful time. A couple of the people had cameras, and everybody enjoyed posing with everybody else.

Then we came back and pulled into the slip where the boat was docked, and we ate and drank some more. “Never been on a boat that big,” people were saying. “Like a fucking ship! You could go to the Bahamas on it!”

It was a great day. Afterward I just put ABSCAM and the boat out of my mind.

Lefty brought his wife, Louise, down to Miami. I went with them to the Thunderbird for dinner and the show. We arrived late, so even though we were tight with the maître d‘, we had to sit at a table right in front of the stage because the joint was packed.

A comedian comes on. I think he was from Australia. He starts working the crowd, cracking jokes at people sitting near the stage, and pretty soon he is focusing on us.

Lefty waves the guy off. “Don’t bother us over here.”

The comedian thinks he has a live one to banter with, so he goes at Lefty with wisecracks.

“I’m telling you, go take your microphone over there.” Lefty points to the other end of the stage.

The guys keeps it up. All of a sudden Lefty goes up on the stage, grabs the mike from the guy, walks it to the far side, plunks it down, and walks back to the guy. “Now that’s the last time I’m gonna tell you.”

Lefty says to me, “If this guy comes back here, you go up and drag him off the fucking stage.”

The guy stays over there but throws a few more barbs at our table. The crowd reacts like this is all part of the act.

When the show ends, Lefty says to me, “Go talk to that guy so he don’t come back over here next show.”

I catch up with the guy and grab his arm. “Hey, pal, next time you’re told something, you listen. We walk in here again, you just make like you don’t even know we’re here.”

“Listen,” he says, pulling away, “this is what I do with the audience all the time, and I’m not changing my act just because you don’t like it.”

I give him a right-hand shot to the stomach, which doubles him over, and start dragging him out toward the back.

The manager has reached us by now. “Donnie, what’s the matter?”

“You saw us try to tell this guy to leave us alone.”

“Yeah, I was trying to catch his eye. Sorry about it. ”

I let the guy walk away. Next day he was fired.

Lefty got a phone call from a New Jersey wiseguy, one of Sam “The Plumber” DeCavalcante’s guys, who was responsible for hiring this comedian. He apologized for what had happened and invited us all back down to the place that night for dinner.

We went for dinner. Everything was on the house from this guy, and he kept apologizing over and over.

“Forget about it,” Lefty says. “The guy was a mutt, that’s all. Donnie straightened him out.”

Chuck, the undercover agent who had the record business and put on concerts back in the beginning of my operation, was working on an operation in Miami on banks that were laundering drug money for Colombian and Cuban customers. The FBI code name was Bancoshares. The mob is always looking for ways to launder money. Chuck thought maybe I could lure the Bonannos in.

I told Lefty about it and suggested that maybe we could steer some customers down there and get a cut. He decided we should go down and meet with the brains behind the scheme. Chuck couldn’t meet with Lefty because he had met him years before when he was a “straight-up” agent-not undercover-in New York City. We brought in Nicholas J. Lore, an agent who had been working in California and has since retired from the F.B.I. to live there. He would pose as a big-shot free-lancer who was the brains behind everything—the guy who put the deals together with all the banks.

I told Lefty that coincidentally, Nick was the guy who owned the boat we went out on, the brother of the woman I knew. It was no more than putting a flesh-and-blood person into the story, instead of just a name, to add reality.

We came down for the meeting with Nick. Lefty was impressed with Nick’s access to big money. Nick wined and dined us at a joint on Key Biscayne. He introduced Lefty to “Tony Fernandez,” an agent who was supposedly his middleman in dealing with the banks. Tony was working with the president of a Miami bank—a Cuban who was deeply involved in laundering drug money through his bank.

Lefty wanted to get a piece of the banker’s action on money laundering by bringing in contacts from New York. He also wanted to get going on some cocaine smuggling. At that time you could buy a key– kilogram—of coke in Colombia for $5,000 to $6,000 and sell it in New York for maybe $45,000. But his attitude on drugs was: To hell with middlemen and cutting profits up with anybody, let’s do it ourselves and keep it to ourselves. Donnie himself can go to Colombia and get the loads. “I don’t need nobody in New York City,” Lefty says. “Donnie comes in with it, nobody knows his business.” Not splitting with the family could get you rich, killed, or both. But since we were dealing with people who weren’t wiseguys-not even Americans—Lefty figured it was worth a shot.

Fernandez put the proposition to this Cuban banker that he do business with Lefty and me, wiseguys from New York. The banker readily agreed and set up a meeting for us at his bank to work out details.

Lefty and I went with Fernandez to this banker’s office. The banker preferred to speak Spanish, so Fernandez was the translator. We sat down and began asking about details of prices and so forth, how the operation would proceed. Suddenly the banker became evasive. He didn’t know anything about the drug business. He didn’t know anything about money laundering. Clearly there would be no deal, and Lefty and I quickly lost patience with this guy’s tap dancing—I wanted the banker busted, Lefty wanted big cocaine bucks.

We left. We couldn’t figure out what spooked this guy. Maybe Lefty, who can be a very intimidating wiseguy, had made him nervous.

It wasn’t Lefty. It was me. Later Fernandez went back to ask him what went wrong. The banker said, “I look in those eyes of Donnie and they’re killer eyes. If something goes wrong in Colombia or anywhere, he’ll come back and kill me. I don’t want to have anything to do with that Donnie.”

Lefty laughed. “I’m the fucking mob killer, and he’s afraid of you.”

But it wasn’t funny to him that we had blown a drug connection in Colombia. Lefty told Nick, “Somebody should sit this banker down and explain to him how you can’t make promises and then back out on it and waste our time. That’s not the way Italians do things.”

An agent going by the name of Tony Rossi was in Florida trying to infiltrate the gambling business that might lead to a connection with the Santo Trafficante family. Trafficante, who had been operating out of Tampa for twenty-five years, was the biggest Mafia don in Florida. He ran gambling casinos in Havana until Castro came to power, and achieved a lot of public notoriety when he admitted participating in a CIA plot to assassinate Castro during the Kennedy administration.

Rossi got a job as an enforcer, a strong-arm guy protecting card games. After a few weeks of this Rossi and the supervisor, Tony Daniels, decided that this wasn’t moving fast enough.

Tony Conte joined Rossi, adding his experience from the Project Timber operation in Milwaukee. They came up with the idea of opening a nightclub. The operation using the nightclub as a way to get to Trafficante was code-named Project Coldwater.

Four case agents worked as contacts for the undercover agents: Jim Kinne, Jackie Case, Bill Garner, and Mike Lunsford. In the fall of 1979, they rented a club in Holiday, in Pasco County, forty miles northwest of Tampa, on busy U.S. Route 19. It was an octagonal building on five acres that had been a tennis club, with six tennis courts. They named it King’s Court.

Rossi was established as “owner.” So that King’s Court didn’t have to deal with the liquor authority, it was a private “bottle club” that you could join for a membership fee of $25. People brought their own bottles and left them in little lockers behind the bar. They paid for setups.

Rossie and Conte hired a manager for the tennis courts, and bartenders, waitresses, a piano player, and a club manager. Nobody knew it was an FBI operation. The club was all redecorated, new bar, new drapes, new oak tables, and padded oak chairs. The front door had a peephole, and signs saying: KING’S COURT PRIVATE LOUNGE; NO BLUE JEANS: MEMBERS AND GUESTS RING BELL TO ENTER.

They started running poker games out of a back room in the club, the house taking five percent. They paid off a member of the Pasco County Sheriffs Department for protection. They managed to entice in some local hoods who pulled small swag deals, drug deals. A couple of the guys that came in had garbage-collection businesses, so they came up with the idea of starting a Cartmen’s Association by which members would control that business in the area and keep newcomers out.

Some half-assed wiseguys began hanging out there—ex-Chicago guys, ex-New York guys. They indicated that they had big connections, maybe leading to Trafficante. But nothing happened.

Conte suggested that maybe I could bring the Bonannos in, like we had done in Milwaukee, and get something going with Trafficante. A liaison with the Florida boss, allowing them to operate in the area, would be just as interesting to the Bonannos as it was to us. We might facilitate a sitdown with Trafficante as we had with Milwaukee. Of course, Conte had to pull out of it. He was leaving, anyway. His past had caught up with him.

All of a sudden, on an October day, word came down from FBI Headquarters that I was to pull out, end the Donnie Brasco role. The Bureau had found out what had spooked Frank Balistrieri in Milwaukee: Balistrieri had learned that Tony Conte was an agent. By mob rules, Balistrieri’s next move should have been to tell the Bonannos in New York. It was just another quick step to them implicating me.

The decision had been made at the top without consulting me. I had to talk them out of it. I was certain that I had laid enough groundwork to continue.

I flew to Chicago to meet with Mike Potkonjak who had been the case agent for Project Timber. I presented my case.

Evidently Balistrieri had not yet passed on his information to New York. We had to assume that eventually he would. Then what would happen?

It was true that there wouldn’t necessarily be any warnings if New York got the word and they decided to ice me. But I didn’t think it would happen. It was true also that I had brought Conte in. But I had been very careful to vouch for him only to a certain extent. If Lefty questioned me, I would say, “Look, like I told you, he and I did some things ten years ago and I had no complaints. So maybe he was an agent ten years ago—so what? I didn’t know about it then, I don’t know anything more now.” Lefty would believe me. Plus, Lefty was in a box. In order to convince Balistrieri of Conte’s reliability, Lefty had told Balistrieri that he himself knew Conte, that Conte was a friend of his. And further, at the Icebreaker Banquet, Balistrieri had introduced Conte as his friend from Baltimore.

Potkonjak was on my side. So was the guy I trusted most in the whole outfit, an old friend, Jules Bonavolonta, coordinator of the Organized Crime Program in New York. But the matter was very intense. We had to work quickly, and all by telephone. We convinced Jimmy Nelson at Headquarters, who was the supervisor on Project Timber and with whom I had worked earlier in New York.

They went to work on the very top levels at Headquarters. Finally everybody came around. I was allowed to continue as Donnie Brasco. But there would remain a lot of concern in Washington. Every once in a while after that, people got nervous for my safety and thought I should come out. To their credit they were convinced, time after time, that I should stay under—that I could survive, that the stuff we were getting was better and better.

I was pretty sure I was right. But from then on this circumstance was always in the back of my mind. Every time I was called in for a meeting with anybody in the family, I wondered whether it might be because Balistrieri had finally passed on his information, and my number had come up.

My wife and daughters flew in to New Jersey to spend the Christmas holidays with relatives.

The day of Christmas Eve is when all the mob guys go around and pay their respects to other wiseguys at all the social clubs. You have a drink with everybody you know. Lefty and I hit all the spots, including CaSa Bella and other restaurants where guys hung out.

Christmas Eve I went to Lefty’s apartment and had dinner with him and Louise. They had a little Christmas tree on the table. Lefty and I exchanged presents-a couple of shirts for him, a couple of shirts for me.

At about eleven o‘clock I went back to Jersey “to see my girl.”

Christmas Day, I went back down to Little Italy to spend the day with Lefty. We cruised around again to the different spots and hung out. At about four P.M., he packed it in for the day, and I went back to Jersey to spend the rest of Christmas with my family.

The day after Christmas, we were all back on the job, hanging out and hustling.

Lefty had finally gotten his son Tommy cleaned up and off drugs. He had sent him to a rehabilitation center in Hawaii. Then he had gotten him a job at the Fulton Fish Market. Tommy was living with a girl and they had a child.

I walk into 116 one afternoon and Lefty is there, steaming. He tells me that Tommy’s girlfriend called him and said that Tommy hasn’t been coming home, hasn’t been giving her money to buy food and necessities for the child. It looked like maybe Tommy was back on junk.

Lefty was seething because Tommy wasn’t taking care of his baby.

“Donnie, he’s supposed to meet me here so I can talk to him. He ain’t showing up. I want you to go find him. I want you to throw him a fucking beating. Then bring him back here.”

I couldn’t beat up his kid, so I stalled for time. “What’s the problem?”

“I just told you the fucking problem.”

“Yeah, but, I mean, is it drugs or the broad or what?”

“Donnie, just find him, do a number, bring him here to me.”

Luckily Tommy walks into the bar and comes over. Lefty lights into him, reads him the riot act about taking care of the child. Tommy tries to explain something, but Lefty won’t hear it. He just wants to ream his son out.

From the fall of 1979 through February of 1980, I gradually cultivated Lefty about King’s Court. I told him a guy I had known from Pittsburgh had come into the Tampa area as a strong-arm, then had opened up a nightclub, and he wasn’t connected with anybody, and he was getting hassled by half-ass wiseguys. There was a possibility that we could move in. Lefty was interested. He wanted me to keep looking it over. Meanwhile Rossi was introducing me to people as his New York connection.

Finally I called Lefty and told him that I was convinced we could make a good score by becoming partners with this guy, and that now was the time to lay claim to the place before anybody else jumped in.

“How much money can we get from this guy, Donnie?” Lefty asks me. “We gotta get at least five grand on my first trip because first I gotta get permission from Sonny to come down, and if he gives me the okay, I gotta give him twenty-five hundred, then out of the other twenty-five hundred I give you your end.”