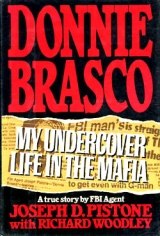

Текст книги "Donnie Brasco: My Undercover Life in the Mafia"

Автор книги: Joseph D. Pistone

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 19 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

Phone calls home were not satisfying. “When are you coming home? Why aren’t you coming home?”

I would talk to each of the girls, ask about school, whether they were keeping the horses fed—they had three horses now that they kept in a barn down the road. Mainly they wanted to know when I was coming home. My wife would say, “Joe, tell me some of the things you’re doing. Knowing where you are, picturing you doing something, that makes me feel more comfortable about it, helps keep my mind clear.”

I would tell her a little bit. If the kids were afraid for me, I’d say, “There’s nothing to be afraid of. These guys are so stupid, they couldn’t find their way out of a paper bag.”

Bills, household problems, teenager problems—I couldn’t do anything about any of it. So much had been going on, guys coming and going in Florida, that I hadn’t been home in seven weeks.

I got home for my oldest daughter’s graduation, the first weekend in June. I was a stranger. A month earlier my wife had fallen while mowing the grass and sliced open her ankle, requiring six stitches. She hadn’t mentioned it. My daughters had gotten into a couple of bad habits—nothing disastrous, just frustrating because I wasn’t there to deal with it. At one point when I was by myself, I put my fist through the bedroom door.

My wife produced a nice brunch party for my daughter’s graduation. My mother was there; her mother was there. I wasn’t in sync. I wasn’t conversational. I was missing a lot of years.

Afterward my wife said, “It was your daughter’s graduation. You should have just forgotten for a while and been happy and put a different face on.”

I had to get back to Florida because Sonny and Lefty were coming down. They had arranged a sitdown with Trafficante. I had been home for three days. “You’ve been in a horrible mood the whole time,” my wife said. She didn’t ask what was wrong. I wouldn’t have known what to answer.

Tuesday morning, June 3, she drove me to the airport. It was our nineteenth wedding anniversary.

When I got to Tampa, I called to apologize for my mood.

Sonny came down with his girlfriend, Judy, and Lefty, and checked into the Tahitian Motor Lodge. Sonny had to wait for a call. Trafficante would say when and where they would meet. We hung around the pool.

The next day he got the call. He was to meet Trafficante that night at eight. He wanted me to pick him up at six forty-five. “I like to get there early,” Sonny says, “and get the feel of the place, look it over to make sure it’s not a setup or there aren’t any cops.”

A top Bonanno captain was meeting with the biggest boss in Florida. The FBI put a surveillance team on.

I took Rossi’s car because it was wired with a Nagra in the trunk. I picked Sonny up. Lefty was not with him.

“We’re going to Pappas,” he says, indicating the restaurant in Tarpon Springs. “He didn’t even say the name. He didn’t have to. He just said ‘I feel like eating Greek tonight.’ I said, ‘I know the place you mean.’ ”

At about seven-fifteen we went into the restaurant. We sat at the bar and had a drink. Sonny scanned the place casually.

“How’s this guy gonna know you?” I ask.

“I met him up in New York last week. I been trying to set this up all along. He was up there. Stevie knew him from years ago. Stevie introduced me to him.”

At about seven-thirty, Sonny says, “Okay, Donnie, you leave, go back to the club, and I’ll call you when it’s time to pick me up.”

I walked out. Going through the parking lot, I passed right by Trafficante and another man heading toward the restaurant. Trafficante was such a quiet-looking old gentleman, shoulders slightly hunched, calm old face. It was odd to think of him as what he really was.

Sonny called at ten o‘clock. I met him in the lounge at the restaurant. We had a drink before we left. I didn’t say anything about having seen Trafficante.

“He’s a dynamite guy,” Sonny says. “He likes me. We got whatever we want. All the doors are open to us in Florida now, just so we do things properly. A fifty-fifty split. If we fuck up, Donnie, the old man will shut every door on us. One of the things we should start looking at, he said, was bingo. He’s big in bingo, but he doesn’t have any in Pasco County. Big money in that.”

In the car, Sonny unwound. “It was a feeling-out conversation,” he says. “I told him, ‘Listen, I’m no sophisticated person. I’m a street person all my life.’ I says, ‘I love the streets, you know. I don’t know nothing about nothing, about gambling or anything.’ I says, ‘Me, I just like to go in the street, rob who the fuck I gotta rob.’ ”

“What did he say?”

“He laughed.”

“He probably likes you because you’re honest.”

“I really respect the man. You show that when you talk.”

“It was a stroke of luck that you met him in New York last week.”

“You know what I told Stevie before? I went down to see him and I says, ‘Hey, Stevie, you gotta come to Florida. I’m telling you now. I never asked you for a motherfucking thing, I’m always alongside you. If you don’t come to fucking Florida with me, I ain’t even gonna fucking come around here no more-just leave me the fuck alone and I’ll do my own thing.’ And I got up and walked out. He called me the next day. He says, ‘Look how lucky we are—the guy is here. We reached right out,’ he says.”

“Is that right?”

“He says, ‘What are you getting mad at me for? I would have come with you,’ he says.”

“So the guy tonight, nice guy to talk to, huh?”

“It’s like me and you talking already, Donnie.”

“That’s great.”

“He was saying stories, you know, about other people. He says other people think like—take this Bruno, for instance, from Philadelphia—he says because you wasn’t born there, Bruno don’t wanna open up the door for you. ‘That’s the wrong thing,’ he says. ‘Like, you come here, I was born here,’ he says, ‘you got something. We’ll work together,’ he says.”

“Well, everybody is gonna be making the money, right?”

“Right, bro.”

We were both happy for the same reason, more or less. I felt deeply satisfied for having engineered a second marriage between two Mafia families.

The next day, Trafficante’s man, Benny Husick, a short, white-haired guy, came to see Sonny about the bingo operation. Afterward Sonny said that Benny ran Trafficante’s bingo parlors. He said that we would start looking for sites with Benny, and that we had to get a building of 8,000 to 10,000 square feet, with air-conditioning. An old supermarket was perfect. He said that we would supply the location and half the money to open it up; Trafficante would supply the equipment and know-how and the other half of the money. We should dream up the name of a charity as sponsoring organization, but the word Italian should not be included. Some kind of disabled war veterans group was good, and you could hire a disabled guy to sit near the door to make it look real.

I started to fill Lefty in on what Sonny had told me about how the sitdown with Trafficante came about, but he knew all about it.

“He was up there in New York,” Lefty says. “What’s the matter, who do you think made all these fucking moves in New York? I did it, not him. Both of us know him.”

“I didn’t think you could sit down with a guy like Trafficante, Left.”

“Uh-huh. Don’t underestimate your goomba.”

Sonny handed me $5,000-fifty $100 bills—to “put on the street” for the loan-sharking operation. He instructed us to “keep the vig,” or interest, and reinvest the capital until it was built into $60,000 to $80,000. Then the split would be me, him, Boobie, and Lefty, with Rossi getting a smaller share.

“For the time being,” he says, “don’t make no loans of more than five hundred bucks. You send two hundred a month to Steve to pay back the family.”

Rossi and I recorded the series year and serial numbers of the bills and turned the money over to the case agents.

Sonny, Judy, and Boobie came down for the Fourth of July weekend. On July 4, Sonny had another meeting with Trafficante. Rossi and I drove Sonny over to Britton Plaza in Tampa, where Trafficante had one of his bingo parlors which his man Husick wanted to show us. Husick took Sonny to the meeting. After his meeting Sonny joined us at the Jack-in-the-Box restaurant.

He was in good spirits. He said that Trafficante liked the dog-track idea, and he told Sonny that he would line up an attorney and an architect. They would be “straight people,” so we shouldn’t discuss mob business with them, Trafficante had told him.

“We gotta get things going,” Sonny says, “because the old man is expecting things to happen. There’s so much fucking money in Florida that if the old man dies, I’ll move right down here and take over the whole state.” He said he was giving up fifteen soldiers in New York, assigning them to other capos, so he could concentrate “on the big stuff in the Florida operation.”

We took a breather. Sonny, Boobie, and I drove out of town to where they had water slides. They give you a little mat to sit on and you climb the stairs fifty or sixty feet in the air and slide down this thing, maybe going twenty miles per hour, and you splash into a big pool at the bottom. We went down every which way—on our bellies, on our backs, making “trains” by locking hands and ankles with each other. We must have spent three or four hours going down the water slides, laughing like kids, taunting each other on who could go fastest.

On Sunday, Sonny, Judy, Rossi, and I took a ride to Orlando so that Sonny could scout the area where he wanted to set up bingo and bookmaking operations, now with the support of the Trafficante organization. Earlier Rossi had said that he had a top Orange County official in his pocket, so Sonny assumed we were under his protection alsa—Orlando was an easy mark.

Then we went to Disney World. It was the first time Sonny had been anyplace like that. We spent the rest of the day, went on all the rides, visited the museums and exhibits, fooled around. We went to a shooting gallery where they had rifles and moving targets. Sonny was a pretty good shot. But Rossi and I were knocking the hell out of everything. “You guys are fucking better shots than I am,” he says. “Where’d you learn to shoot like that?”

He could relax easier than Lefty could. Lefty was Mafia twenty-four hours a day. Mafia business was always intertwined with everything Lefty did with me. He would never let his guard down. Despite the fact that Sonny was more powerful and more dangerous, it was a relief to be with him. In restaurants or in public, he was a gentleman, not a loudmouth. I didn’t have to carry his bags. Away from mob business, Sonny was just a regular street guy who could laugh and break chops. No business was discussed when we were having a good time.

His girlfriend, Judy, was a good kid, a straight girl, sharp. She didn’t know much about what he did. He never involved her in anything of the business. She was his main girlfriend. He had met her when she was tending bar at CaSa Bella. She was another one of those outsiders that I was sorry about, because of what would happen down the line.

At a roadside stand, Sonny saw little baby palm trees in pots. He decided he wanted some back in Brooklyn, to plant outdoors. “Palm trees would look great up there,” he says. “It would knock people out.”

“Palm trees are for tropical climates,” I say. “They won’t last the winter in Brooklyn.”

“As long as they live through the summertime,” he says, “what’s the difference? Nothing lives forever.”

So we bought five or six and shipped them Federal Express to Brooklyn.

Sonny wasn’t any good at tennis, but he loved to play. He would take the court at King’s Court in his black socks. Rossi and I would play doubles against him and Boobie. Sonny would run around whacking at the ball and hollering at us, “I’m gonna kill you!”

Sometimes he and I would arm-wrestle. Sonny lifted weights. So did I. He was strong, but I had the advantage of leverage, being taller and having longer arms. We would be sitting around the pool or someplace when he would challenge me. He could never beat me. It drove him nuts. I never saw him challenge anybody else. But he never stopped challenging me.

One day Sonny brought a bottle of pills to the club. The pills were called Zooms and they were supposed to enhance your sex life. Sonny gave the bottle to Chico. “These were made by the virgin nuns of Peru,” he tells Chico. “They keep your pecker hard. You’re gonna love them. Give one to Donnie to try too. Let all the guys try it.”

Chico took the bottle home. We knew they were just some caffeine concoction. The next day Chico came into the club. “Wow, they were sensational, those Zooms,” he says to Sonny.

“Great, right?” Sonny says. “You give one to Donnie?”

“Naw, I took them all,” Chico says, “all twenty.”

“You took them all! You must be crazy!”

“The thing is, I just can’t get it to go down now. I push on it and slap it, it won’t go down.”

“You crazy bastard! You can’t use Zooms like they was a fucking toy! They come from Peru! You’re lucky you’re alive!”

Since we were now dealing with Trafficante, we wanted to keep King’s Court clean, relatively. We didn’t want to attract more attention than necessary to the club as a gambling place. So we opened up another club for the card games. It was just a small store, at 1227 Dixie Highway, a couple of miles away. Sonny gave me $500 for the security deposit. We took the card tables out of the back room of King’s Court and sent them off down there, with the poker dealers, and that’s where the nightly games continued.

“We gotta do things right,” Sonny says. “The old man says he has five hundred men down here and they’re not pulling their weight. He’s looking for new blood in this state, and that’s us.”

Rossi had met a guy named Teddy who was a book-maker in the area. Teddy wanted to run the football book for us. We arranged for him to meet Sonny. The five of us—Teddy, me, Rossi, Sonny, and Lefty—sat around the pool at the Tahitian. Teddy said he ran a big-time book. Sonny grilled him. He asked him how long he had been booking, how much action he was taking, how he ran the business, everything.

After Teddy left, Sonny says, “I don’t want to do business with this guy: He thinks he’s too sharp. I think he’d end up trying to fuck us, and then I’d end up having to kill him. For now, let Jo-Jo take the bets over the phone, and Chico can handle payments and collections.”

Sonny was shuttling between New York and Florida for meetings with Trafficante, solidifying his position. On August 8, he and Lefty came down. Sonny called me at the apartment and said for me and Rossi to be at the coffee shop at the Tahitian at three-thirty in the afternoon. “That guy is coming,” he says.

I decided to carry a transmitter.

I met our contact and picked up the transmitter. Rossi and I tested it in my apartment. Rossi put in a call to agent Mike Lunsford, who was on location. I spoke into the transmitter. Lunsford couldn’t hear anything coming over the radio. We tried it again and again as time drew short. Lunsford wasn’t picking up anything.

Rossi says, “What the fuck we got all this fancy equipment for if it doesn’t work?”

It’s hard to explain to anybody how it makes you feel. You risk your life and exposure of the operation by carrying this piece of equipment. You go through maybe a whole day or night with this on you. You think you’ve got some dynamite conversations. But nothing came in on the receiver, or all you got on your tape was beeps and noises, or just silence. It was good equipment. Maybe it was used a lot before they gave it to you. There’s no way to know when it’s going to malfunction.

If I got caught with a transmitter, the first thing these guys would think is that I was an informant. If you’re a cop or an agent, maybe they’ll think twice because you’re doing your job. I had been with these guys four years now. There’s no way they would believe I was an agent. They would think I just turned and went bad. No leeway. They would kill me.

So here I was about to go out with Sonny Black, who was going to meet with Santo Trafficante, and I had a piece-of-shit transmitter. It was better to find out ahead of time. But the more. Rossi and I tried to make it work and the more we talked about it, the more aggravated we got.

Finally I wound up and threw the transmitter at the wall. It hit right next to the window and clanked down on the floor, bent and sprung. “At least nobody else will get stuck with this piece-of-shit transmitter,” I say.

Rossi and I went to the coffee shop. Sonny was sitting at a table with Trafficante and Husick. He motioned for us to sit at another table by ourselves. Husick came over and wanted us to take him to look at a potential bingo site on Ridge Road in New Port Richey. When we came back, Sonny and Trafficante were still talking. Sonny told us to sit at the counter.

Half an hour later Sonny came over and told Rossi to make dinner reservations for three at the Bon Appetit restaurant in Dunedin. “You guys go up to Lefty’s room,” he says.

Lefty’s room was next to Sonny’s. Lefty was lying on the bed watching TV. Rossi got on the phone as instructed. I was standing in the doorway.

Sonny and Trafficante came walking by. Sonny motioned for me to come into his room. Inside, he introduced me.

“Donnie, this is Santo. Santo, Donnie.” Santo looked at me with narrow eyes through thick glasses. I shook hands with my second Mafia boss.

15

DRUGS AND GUNS

Sonny wanted me to come to New York to update him on all the various rackets we supposedly had under way—bingo, numbers, gambling. I went to his neighborhood for the first time.

The Withers Italian-American War Veterans Club, Inc., Sonny’s private social club, was at 415 Graham Avenue, at the corner of Graham and Withers Street in the Greenpoint section of Brooklyn. The neighborhood was quiet, safe, and clean, mostly small shops and storefront businesses in two-story or three-story apartment buildings. It was similar to the neighborhood in the Bensonhurst section to the south, where I had been involved four years earlier with Jilly’s crew and the Colombos. One of the main similarities was that both neighborhoods gave you the feeling that outsiders would be noticed quickly.

The Withers club had a big front room with a small bar and a few card tables, and a back room with a desk, telephones, a sink, and the men’s room.

Diagonally across the intersection, at 420 Graham Street, was the Motion Lounge, another private hangout for Sonny and his crew. There was no sign at the front door. The exterior wall of the club was covered with fake fieldstone siding. The upper floor of the three-story building was sheathed with brown shingles. In the front room of the lounge was the bar, a large-screen projection TV, a pinball machine, a couple of tables. Behind the bar was a big tank of tropical fish. In the back room was a small stage, a pool table, a jukebox, a few card tables. A kitchen was off the back room.

As it was with the clubs in Little Italy, the wiseguys in Sonny’s crew lounged around inside and outside during the summer. Their cars—mostly Cadillacs—were parked and double-parked on the block.

Sonny said I shouldn’t bother with the expense and inconvenience of a hotel; I should stay at his apartment. That was on the top floor above the Motion Lounge, a three-story walk-up. It was a modest, utilitarian one-bedroom place. You entered into a hallway with a small kitchen to the left, a dining room ahead, and a living room with a pullout sofa bed to the right, and Sonny’s bedroom off that. There were no doors. A sort of ladderlike set of stairs led up to the roof, where he kept his racing pigeons.

He didn’t have air-conditioning in the apartment, because the building wasn’t wired for it, and the heat that night was brutal. He kept the windows open, which looked out over the adjoining roof. I slept on the pullout couch in the living room; he slept in the bedroom.

I fell asleep on my back, sweating. I woke up. Something touched my chest. At first, in my daze, I thought it was hands, fingernails feeling for my neck—somebody was going to strangle me.

But it was claws—a rat!

I froze, afraid to open my eyes. Sleeping in the apartment of a Mafia captain didn’t bother me at all. But I am terrified of mice or rats. I shudder when I see them dead or alive. If there is a mouse in my home, my wife or kids have to deal with it.

Now I was going to get bitten by a rat and die of rabies.

I held my breath while I counted down. Then I swung my hand with everything I had and swatted it across the room. The rat thudded to the floor as I hit the light switch.

It was a cat I glimpsed, leaping for the window and disappearing into the night across the rooftops.

Sonny came running in. “What the fuck happened?”

I told him. He started laughing like a son of a bitch. “Big, tough guy, scared of a fucking cat,” he says. “Wait till I tell everybody this story.”

I was shaking. “Sonny, you better not tell anybody this story, not anybody. If you got some fucking air-conditioning in here, we wouldn’t have to leave the windows open and let any fucking animal in the world in here.”

“Okay.”

“Anybody could come in through that window, Sonny, it ain’t safe.”

“Okay, okay.” He went back to his bedroom, still laughing.

At about six-thirty he woke me up. He had already been to the bakery across the street to pick up pastry and had made coffee. We sat around his kitchen table in our underwear, drinking coffee and bullshitting about the business.

He had weights and a weight bench in his bedroom. We lifted weights together.

We went up on the roof so he could show me his pigeons.

He was proud of his racing pigeons. He loved to spend time up on the roof. He had three coops. Both the roof of the building and the roof of his coops were topped with miniature white picket fences.

He told me about blending their food, adding vitamins for stamina. He explained about the different breeds, how you matched different breeds to get birds that could fly long distances. Each pigeon had a band on its leg for identification. He said there were lots of races in different cities. The pigeons would fly home to their coops. Owners had a clock that would stamp the time on the band. He said you could win up to $3,000.

He said he did some of his best thinking up on the roof taking care of his pigeons.

As a kid growing up in that same neighborhood, he told me, he was just a thief in the streets. “I didn’t care about being a mob guy. I was doing good enough.” But then he got to a point where he couldn’t do anything without the approval of the local mob guy in his neighborhood. “So it was easier to join them than to fight them.” He became a hijacker and stickup man, and eventually served time.

He talked about mob politics. The Colombo family was in bad shape because both Carmine and Allie Boy Persico were under indictment. He hinted that the power struggle was heating up within the Bonanno family.

“The whole thing is how strong you are and how much power you got and how fucking mean you are—that’s what makes you rise in the mob.” Sonny would repeat the theme time and time again in conversations with me up on the roof with his pigeons. “Every day is a fucking struggle, because you don’t know who’s looking to knock you off, especially when you become a captain or boss. Every day somebody’s looking to dispose of you and take your position. You always got to be on your toes. Every fucking day is a scam day to keep your power and position.”

When we were around other mob guys, it was different. Sonny acted like a captain and commanded respect. On the street and in other business situations, you could see that he was not only respected but feared. But here, when nobody else was around, we just shot the breeze like two equals. He talked about how much he loved his kids. He was very optimistic about Florida. He encouraged me to move on drug deals. He wanted us to get going on plans for another Las Vegas Night.

He gave me my own key so that I could use his apartment anytime I wanted, whether he was there or not. Sometimes he stayed at Judy’s apartment on Staten Island. From then on I stayed at Sonny’s almost every time I came to New York.

When I went back down to Florida, I sent Sonny a pair of ceiling fans for his apartment. He sent me a big package of canned squid, Italian bread, Italian cold cuts and cheeses, because he knew I loved those things and I couldn’t get the best New York-type stuff where I was in Florida.

Sonny was not satisfied with the volume in our bookmaking and shylock business. He wanted to send somebody down from New York to run it. Rossi and I had a better idea: my friend from Philadelphia, an agent whose undercover name was Eddie Shannon. I had known Shannon since 1968, when he was a detective in the Philadelphia Police Department and I was with Naval Intelligence. He had run an undercover bookmaking business in Baltimore.

“I got a guy that could do the book,” I tell Sonny. “He’s not Italian, he’s Irish, but he’s good.” I filled him in. “Next time you come down here, I’ll have him come down. You can get to know him, talk to him alone. If you like the guy, fine. You make the decision. If you want him to stay with us, he’ll stay, because he owes me some favors.”

“Now we gotta deal with a fucking Irishman,” Sonny says.

Sonny came down and spent a couple of days getting to know Eddie Shannon. Then he says, “I like the kid. He’s sharp, knowledgeable. He’s got a lot of loyalty to you, a stand-up guy. I like that. Get him an apartment down here and tell him to move in.”

Shannon got an apartment in the same complex where Rossi and I lived, the same complex in which other agents received and monitored the microwave video transmissions from King’s Court.

Rossi and I were continually working on potential drug deals. That is, we worked to line them up and then tap-danced to keep them from happening. We had to encourage drug sources by promoting our contacts and outlets, how much we could move through “our” people. We had to keep Sonny and Lefty interested by promoting the capabilities of our drug sources. But we couldn’t let any big deals happen. Nor could we have any busts that would compromise our operation. So the trick was to contact sellers, drag information out of them, keep them on the hook, and keep Sonny and Lefty excited—all while keeping the two sides apart.

Our contacts were ready to provide a wide range of products. We had a local guy with coke to sell at $15,000 a pound. We had a guy peddling Quaaludes for eighty or ninety cents apiece, and grass for $230 to $240 a pound. There was a coke dealer in Cocoa Beach. We had a guy with heroin samples from Mexico, and a twin-engined Piper Aztec he used to fly loads in. One local guy said that if we could find him a plane, he could make $1 million in two months on trips to Colombia where he could get cocaine that was ninety percent pure. He needed $25,000 front money to set it up and would charge $50,000 per trip. This same guy said he could get “ ‘ludes” in South America for twenty cents each. We kept talking to them all, going back and forth with prices, questions, promises, broken promises.

“In my FBI file,” Lefty says to Rossi and me, “it says ‘This man hates junk.’ Right next to my picture.”

We were talking about how many young millionaires there were in south Florida who had made their fortunes in the drug business.

Sonny was always talking about heroin, cocaine, marijuana, Quaaludes. One time he tells me, “Don’t bother with the coke right now. The hard stuff and the smoke is what’s selling big now in New York.” He had one outlet immediately for 300 pounds of grass and another for 400 pounds. “I want a steady source that can provide a hundred pounds a week. I could net ten grand a week from the outlets I got. We’ll have twenty grand to pay for the first load up front.”

On the phone, one of our code phrases for drugs was “pigeon feed.” Over the phone I was telling him about a new connection. He said, “Bring a sample of the pigeon feed up to New York,” so he could have it checked out.

Rossi put a sample in his pocket and we flew to New York. At JFK we were met by Boobie. He introduced us to Nicky Santora. Nicky, an overweight, curly-haired, happy-go-lucky type, was in Sonny’s crew.

Boobie asked if I had the sample.

“The marijuana? Tony’s got it.”

“I thought you were bringing heroin.”

“I thought Sonny meant marijuana. We got our signals crossed, I guess.”

Boobie was upset because he had a friend standing by to test the sample of heroin.

“We’ll bring that on the next trip,” I say.

Nicky drove us to Little Neck, on Long Island, where Sonny was staying temporarily. Nicky talked about the bookmaking business. He had just recently gotten out of jail. “I was convicted for taking four bets over the telephone,” he says. “Can you imagine that?”

Sonny was staying with a guy named John Palzolla in the North Shore Apartments in Little Neck.

Sonny says, “You told me you had a sample of heroin.” “

“No, I didn’t.”

“Well, fuck it. Give the sample to Nicky. Maybe he can do something with it.”

Rossi handed Nicky the small plastic bag of grass.

“The guy wants two hundred and seventy a pound,” I say.

“That’s high,” Sonny says.

“Maybe we can get three-fifty to four hundred a pound in the city,” Nicky says, looking at the stuff.

“It’s got a lot of seeds. I’ll take it out tomorrow and shop it around to a few people.”

A bunch of us met downstairs for dinner at the Chop House Restaurant, which was in the apartment building. Sonny’s cousin, Carmine, was there. Nino, Frankie, Jimmy—last names weren’t used. A few women came around, including one named Sabina. Sabina took a joint rolled from our grass sample and went away for an hour. When she came back, she said, “Gee, that wasn’t bad stuff.”

Everybody talked about what they had going. Carmine said he had a lot of fugazy jewelry available—fake Rolex watches, vermeil trinkets, gold charms. Rossi agreed to take some back to sell at the club.

John was awaiting sentencing for “Ponzi” schemes that he and his brother had conducted around the country. He said a good way to work a Ponzi scheme was to go to some rich guy who needs to put his money someplace and tell him that you have connections with a clothing manufacturer who produces a lot of overruns. And these surpluses—jeans or whatever—are available at a fraction of wholesale. If this person invests, say $5,000, you can guarantee $500 return for the first week. The return is so fantastic that more and more people invest, and they invest more and more. You give them these great interest payments, but you keep the capital. When you get enough capital, you “skip town and never see these investors again.”