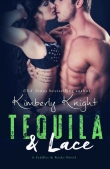

Текст книги "Donnie Brasco: My Undercover Life in the Mafia"

Автор книги: Joseph D. Pistone

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 8 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

Recollections came rushing into my head. The guy in Jilly’s that I recognized as somebody I had once arrested—had he known me, after all? Guido’s remarks about Allie Boy Persico—had those remarks about his son gotten back to The Snake? The recollections didn’t make me feel good. Was I going to be grilled about Jilly’s crew, things I had heard, what I was doing there?

If The Snake had heard about the complaints, was I going to be pressured to rat out the people doing the complaining? If I was pressured for information, would it be some kind of test?

My mind was racing as we cruised over the Brooklyn Bridge. I tried to sort out the possibilities and options. I definitely would not rat anybody out. That was for sure. If I turned rat on anybody to save my own skin, I would have to pull out of the operation, anyway, because my credibility would be blown. So if I was pressured to rat anybody out, I would just take the heat and see what happened. If they were testing my reliability, I would pass the test, and that would put me in solid.

Unless, of course, they really wanted me to talk, and decided to hit me if I didn’t. They could whack me out over there and dump me in the Gowanus Canal where I wouldn’t be found until I was unrecognizable. Nobody would know.

Mirra was silent. We drove to Third Avenue and Carroll Street in the Park Slope section of Brooklyn, not far from Prospect Park. We parked and waited. Carmine Persico drove up in a white Rolls-Royce convertible with New Jersey plates—444-FLA. I recognized him from pictures. A sturdy guy in his middle forties, with thinning hair, a long neck, baggy eyes, and a fleshy nose and mouth. He and a much younger man, maybe in his early twenties, got out of the Rolls and talked to Mirra for a few minutes.

When Mirra got back in the car, he said, “That was his son with him, Allie Boy. He just got straightened out.”

“Straightened out” means made. I didn’t say anything.

“Tommy LaBella’s supposed to be the Colombo boss,” Mirra said, “but that’s in name only, because he’s so old and sick. The Snake is the real boss. I had to talk to him about a shylock business we’re trying to put together with him.”

A shylock business between the Bonanno and Colombo families was all it was. I was so primed, I actually felt a letdown. Given the options, I’ll take a letdown.

You could never relax with these guys, because you never knew what would be heavy-duty and what would be light.

I was getting itchy. Jilly’s crew seemed to be a dead end. One of my functions was to gather evidence to make cases directly. Another was to gather intelligence that the government might use in other investigations. At the time you hear or see things, you can’t always know how important they are, which way the information might be used, or whether it might be useless. You’re reluctant to ignore anything, but you can’t recall and report everything. You have to make choices on who and what to focus your concentration upon. How effective your choices turn out to be depends upon experience, instinct, and luck.

By midsummer of 1977, we had enough information on hijackings, burglaries, and robberies to bust up Jilly’s crew any day in the week. But I wasn’t moving up. I was making more inroads with Mirra and Ruggiero and the wiseguys in Little Italy than I was with the fences in Brooklyn.

I began to think, instead of concentrating on fences, what about a direct shot at the Mafia?

I brought this up in a telephone conversation with my supervisor, Guy Berada. It intrigued us both. We even risked a rare meeting in person, for lunch at a Third Avenue Manhattan restaurant called Cockeyed Clams, near my apartment.

We reevaluated our goals. The more we thought about it, the more we thought, if I get hooked up with a fence, that’s all I’m hooked up with. But the Mafia had a structure and hierarchy; if I could get hooked up with wiseguys, I had a chance at a significant penetration of the mob itself.

It would mean a greater commitment from the Bureau, an increase in risks and pressures. So far as we knew, the FBI had never planted one of its own agents in the Mafia.

Finally the opportunities outweighed all other considerations. It was worth a shot to abandon the fence operation in Brooklyn and “go downtown,” throw in with the wiseguys in Little Italy.

I would continue to operate alone, without surveillance. Little Italy is a tight neighborhood, like a separate world. You couldn’t park a van with one-way glass on a street down there without getting made in five minutes. I would continue to operate without using hidden tape recorders or transmitters because I was still new, and there was always the danger of getting patted down. The Bureau had informants in Little Italy. They wouldn’t know who I was, I wouldn’t know who they were. I didn’t want to risk acting different around somebody because I knew he was an informant, or having somebody act different around me.

Having made the decision, I couldn’t just abruptly drop out of the Brooklyn scene. I still had to use the Brooklyn guys as backup for credibility. In all likelihood, sooner or later the downtown guys would check me out with the Brooklyn crew, and I didn’t want any of Jilly’s guys to say I just disappeared one day. I wanted to ease out gradually.

I hung out more and more with Mirra and Ruggiero, less and less with Jilly’s crew. Gradually it got to where I was just phoning in to Jilly once in a while. By August I was full-time around Little Italy.

Jilly stayed loyal. Agents routinely show up to talk to wiseguys like Jilly, show pictures of people they’re interested in, see if you have anything to say, let you know they’re keeping tabs on you. One such time, agents came out to talk to him. They showed him several pictures, including a picture of me. These agents didn’t know who I really was. They told him that I was a jewel thief and burglar, that they had information that I was hanging out around there, and they wanted to know what he knew about me.

Jilly wouldn’t acknowledge whether he knew me or not. Even though I wasn’t around there anymore, he wouldn’t give up anything about me.

Two years later Jilly got whacked. He was driving his car near his apartment. He stopped for a red light and some guy on a motorcycle pulled up beside him and pumped a couple of .38 slugs into him. It was a regular mob hit. Our information was that they thought Jilly was talking. But he wasn’t.

7

TONY MIRRA

J Edgar Hoover didn’t want his FBI agents to work undercover because it could be a dirty job that could end up tainting the agents. Times have changed. Undercover work is now a crucial tool in law enforcement.

Informants are valuable but unreliable. They are crooks buying their life-style or freedom with information, and they may lie or exaggerate to get a better deal. A government agent working undercover, sworn and paid to uphold the law, is more trustworthy, more credible, before a jury. But it’s a risky business. You can get dirty, you can get killed.

Not every agent can work undercover. You have to have a strong personality. Strong means disciplined, controlled, confident. It doesn’t mean loud or abrasive or conspicuous. It means your personality can withstand the extraordinary challenges and temptations that routinely go with the work. It means you have an ego strong enough to sustain you from within, when nobody but you knows what you’re really doing and thinking.

It means you don’t forget who you are, not for a day, not for a minute. You are an FBI agent making a case.

You have to be an individualist who doesn’t mind working alone. Really alone, more alone than being by yourself. You’re with badguys continually, pretending to be one of them, cultivating them, laughing at their jokes, keeping feelings and opinions and fears to yourself, just like your true identity. You do this all day, every day. You don’t leave this life every once in a while to share stories with friends or family about what’s been going on undercover. You have nobody to talk to about what you’re experiencing, except your contact agent. I talked to my contact agent for a few minutes by telephone maybe a couple of times a week. I saw him for a few minutes once a month, to pick up my spending money.

While you are pretending to be somebody else, there are the same personality conflicts you would find anywhere. There are guys you like and don’t like, guys who like you and don’t like you and will continually try to bust your balls. You have to override your natural inclinations for association. You cultivate whoever can help you make a case. You’re not a patsy, but you swallow your gripes and control your temper.

You have to make difficult decisions on your own and often right on the spot—which way to go and how far; what risks to take. You have to accept the embarrassment and danger of being wrong and making mistakes, because you have nobody to hide behind on the street, and you are always open to second-guessing from your superiors. In my case that meant even the top FBI bosses in Washington.

You have to be street-smart, even cocky sometimes. Every good undercover agent I have known grew up on the street, like I did, and was a good street agent before becoming an undercover agent. On the street you learn what’s what and who’s who. You learn how to read situations and handle yourself. You can’t fake the ability. It shows.

You have to be disciplined to work, be a self-starter. The law-enforcement business basically has a conservative atmosphere. Employees are used to rules and regulations. In the FBI, nobody is hired as an undercover agent. You’re brought in as a regular agent. You go to work in a tie and jacket. You sign in and you sign out.

After several years, take a regular agent and put him in an undercover capacity. Suddenly nobody tells him when to go to work. Nobody tells him what kind of clothes to wear. He dresses like the badguys. Maybe he drives a Cadillac or Mercedes. Chances are he has his own apartment, regardless of whether he’s married or not, and he comes and goes as he pleases. He has money to spend.

This life-style is provided by the FBI. It’s all Hollywood, phony. But all the guys around you have Caddies and pinkie rings and broads and cash, and it’s easy to forget that you’re not one of them. If you don’t have a strong personality and ego, a sense of pride in yourself, you’re going to be overcome by all this, consumed by the role you’re playing. The major failure among guys working undercover for any law-enforcement agency is that they fall in love with the role. They become the role. They forget who they are.

I grew up in a city, an Italian, knowing what the Mafia was. As a teenager I played cards, shot craps, played pool, went to the track, hung around social clubs. I knew that some card and crap games were run by the mob, and some social clubs were mob social clubs. I knew some guys who were mob guys. I knew that maybe the bookie wasn’t a made guy, but his boss was, the guy who ran the whole operation. I knew some of them were killers. Even as a kid I knew guys that were here today, gone tomorrow, never seen again, and I knew what had happened.

I knew how wiseguys acted. I knew the mentality. I knew things to do and not to do. Keep your mouth shut at certain times. Don’t get involved in things that don’t concern you. Walk away from conversations and situations that aren’t your business, before anybody asks you to take a hike. You handle yourself right in those situations, that’s how you get credibility on the street. They say to themselves, “Hey, this guy’s been around.”

It helped me in my undercover role, knowing this stuff going in.

Growing up in that environment, I could have gone the wiseguy route. I knew guys that did. It happened that my mother and father were straight, and I grew up with their values. I grew up as a guy who would work for a living, raise a family, obey the laws. Other guys became badguys.

I don’t moralize about that. Because of how and where I grew up, the Mafia held no big mystique for me. I didn’t go into this job as any crusade against the Mafia. I might be saying to myself, “These fuckers, they’re killing people. They’re lying and stealing. They’re badguys, and I don’t like badguys.” But I don’t have to overcome a moralistic contempt that could get in the way of my job. I’m not a social worker, I’m an FBI agent. If my field as an agent had been civil rights or terrorists, I would have gone at it the same way—done my job to the best of my ability.

If you’re a badguy, my job is to put you in the can. Simple as that.

The Mafia is not primarily an organization of murderers. First and foremost, the Mafia is made up of thieves. It is driven by greed and controlled by fear. Working undercover, I was learning how tough these guys really were, how tough they really weren‘t, and how the toughest among them feared their superiors.

It wasn’t the toughness of an individual that caused the fear so much. It was the structure. It was the system of hierarchy, rules, and penalties that can terrify the toughest wiseguy in the business. The more potent toughness is in the ability to enforce the rules.

Everything is done to make money. Some violations may be excused if you’re a good money-maker. Murder is secondary, the tool of enforcement, the threat. You can be as frail as was old Carlo Gambino—the last real Godfather, Boss of Bosses—before he died in 1976, but if by a simple yes or no, a nod or a shake of the head, or a waggle of the finger you have the power of death over anybody in your organization, there isn’t a gorilla on the street who won’t shake in his Bally shoes before you.

The five major Mafia families are based in New York: Gambino, Lucchese, Genovese, Colombo, Bonanno. Joe Bonanno took over the family in 1931. He was forced into retirement in the mid-1960s and now lives in ill health in Tucson, Arizona. The Bonanno boss when I went undercover was Carmine Galante.

The Gambino family was run by Big Paul Castellano; the Lucchese by Anthony “Tony Ducks” Corallo; the Genovese by Anthony “Fat Tony” Salerno; the Colombo by Tommy LaBella. Each boss has absolute authority over his family.

The Commission, on which sit the bosses of the families, resolves interfamily disputes or matters that transcend the interests of a single family, or allows for cooperative ventures, such as controlling the concrete industry in New York or skimming the take from the Las Vegas casinos. A transcendent matter may be whether the boss of a family should be hit. The Commission has to approve the execution of any boss by either a faction of his own family or by anybody else.

Beneath each boss in a family, each level of the chain of command requires total respect from those below. Each family has an underboss; a consiglieri (counselor), who mediates disputes and advises the boss; and a number of captains. Under each captain are the soldiers, the lowest level of made guys.

Then there are a lot of “connected” guys who are associated with the made guys but are not themselves made. In any family there may be, say, two hundred made guys and ten times as many connected guys. If you are a connected guy, in partnership with some soldier or captain, you are subject to many of the same rules as everybody else in the family. You have to give respect, you have to share your profits. But they don’t necessarily share with you. And you are not entitled to the same respect and protection given to made guys.

In spite of how much I knew about the Mafia—both from growing up and from research—I was learning a lot. It was different being on the scene, being part of it, experiencing it firsthand. As with any law-enforcement agency, we knew a lot more than we could prove in court. So what I could come up with firsthand, on the scene, was crucial.

I was already identifying a lot of guys in the Colombo and Bonanno families, and pinpointing their ranks. I was learning that more hijacks were “give-ups” than regular hijackings. Whenever you pulled a score, you had to give a cut of it to whoever you were responsible to above you in the chain of command. You had to report to your captain or boss on everything you did. Despite these rules, though, there was more swindling of one another going on in crews than we had thought.

Along with the strict chain of command and the requirement for respect for those above you, there was a strict code of discipline. The consequence for not adhering to the rules of profit sharing and respect was not getting kicked out of the Mafia, it was being whacked out.

I was learning how it felt to be a part of this system. I was learning to act accordingly. I was becoming ever more known and trusted, was in on their plans and activities, and so had to start abiding by the rules of the mob.

It was amazing that I had been accepted at all. Everybody around me had grown up in these neighborhoods, been known forever. I was a newcomer. So far they had bought my stories and style. And I had been lucky. When you’re an FBI agent running with thieves and killers, no amount of skill is itself enough to keep you alive and effective. You’ve got to get the breaks too.

I was in at the bottom. The only people lower than me by Mafia reckoning were ordinary citizens with nine-to-five jobs and no mob connections.

Anthony Mirra was the nastiest, most intimidating guy I met in the Mafia. He went about 6’2”, 210 pounds. He was a good money-maker and a stone-cold killer. He was moody and unpredictable. You never knew what might set him off. And when he snapped, he might do anything.

Mirra was a knife man. It was common for mobsters to carry knives instead of guns, because they were often rousted by cops and didn’t want to be caught with guns on them. Being caught carrying an unregistered pistol in New York means prison. They carried folding knives with long blades. I carried one. But it was not common for everybody to use their knives the way Mirra did. I was often told, “If you ever get into an argument with him, make sure you stay an arm’s length away, because he will stick you.” Even among mafiosi, Mirra was far from normal.

He was always in trouble, either with the law or with other wiseguys. He was totally obnoxious, he insulted everybody. He was widely despised but just as widely feared. A lot of people just tried to stay out of his way.

“Mirra’s problem,” Lefty Ruggiero told me, “is that he’s always abusing somebody.”

But for me he was a step up from Jilly’s crew in importance. He accepted me, and I started hanging out with him, dividing my time between him and Jilly’s Brooklyn crew. I would go to Little Italy for a couple of hours in the morning, then head over to Brooklyn for a while, then come back to bounce around with Mirra at night. We’d hit discos like Cecil‘s, Hippopotamus, or Ibis.

Mirra never spent his own money. Everything was “on the arm”—free with him. One of the first times I was with him we were at Hippopotamus. A lot of wiseguys hanging out there came over to talk to him. We were at the bar half the night, not paying for anything.

When we got up to leave, I put $25 down on the bar.

“Take that fucking money off the bar,” Mirra growled at me in his deep voice. “Nobody pays for nothing when they’re with me.”

“Geez, Tony, just a tip for the bartender,” I said. “That’s how I operate.”

He jabbed a finger in my chest. “You operate how I tell you to operate. Pick it up.”

“Okay, Tony,” I said, and I pocketed the bills. I wanted to avoid a big argument with him, and possible consequences. But it was not easy, letting somebody like that talk to you like that.

Mirra told me that Hippopotamus was owned by Aniello Dellacroce, the underboss of the Gambino family. Mirra introduced me to Aniello’s son, Armond, who he said ran the place.

Armond had an illegal “after-hours” place at 11 West Fifty-sixth Street, with blackjack and dice tables and a roulette wheel. I went there with Mirra a few times. It was a comfortable, carpeted place, free food and booze, all kinds of girls waiting on you while you gambled. It opened at two or three in the morning and ran until maybe eight or nine.

Aniello Dellacroce died of cancer in 1985, while under indictment on RICO charges; soon after that, Armond pled guilty to federal racketeering charges, but he disappeared before sentencing and at this writing is still a fugitive.

We were at a bar in Fort Lee, New Jersey. Tony was talking to some guy on the other side of him and I was listening. I moved my elbow and knocked over my drink, spilling it on the guy on my other side. “Sorry,” I say.

“ ‘Sorry’ don’t clean my coat,” the guy says. “Why don’t you assholes go back to New York where you belong.”

“Hey, I said I’m sorry.” I get a bar rag from the bartender and wipe it up.

Now this guy gets a drink, puts it on the bar, and knocks it over on me. “Take your dumb ass back across the river,” he says.

Nothing’s going to appease this guy. I see Tony listening to this, getting that cuckoo look in his eye, his hand in his jacket pocket.

My theory is, you don’t get into an argument because you don’t know what will develop—some guy pulls a gun or goes outside and brings back twenty guys. Plus Mirra may be on the verge of pulling out his knife to stick this guy. I have to end it quick.

I say, “You wanna step outside?”

“Yeah.” He gets up off his stool, and I give him a shot right there, because I’m not going outside. Another guy jumps in, Mirra smacks him. The first guy comes at me again, I clock him with a bottle.

I say to Mirra, “Let’s get the fuck outa here.”

“Yeah, let’s go,” he says.

We scram before the cops come.

“Why didn’t you just stick the cocksucker?” Tony says. “I was gonna do it for you.”

Embarrassed? Yeah, I was. Here I am an FBI agent, a thirty-eight-year-old man, getting into a bar fight. I didn’t even want to be in that joint with Anthony Mirra. But because I was, that’s the kind of thing that can happen. And when it does, the best thing you can do is handle it quick so it doesn’t get out of control. I don’t believe in arguing.

Often on Friday and Saturday nights we hung out at Cecil’s. I learned that Cecil’s was one of the joints Mirra had muscled in on. The owners paid him a weekly cut, a salary for the privilege of having him around. Sometimes he’d tell me to watch the bartenders and manager to make sure they weren’t clipping the joint.

If he didn’t make $5,000 there on a weekend, he went cuckoo. One Friday night, out of the blue he decided he wasn’t making enough money out of the joint, so everybody would be charged five dollars at the door. The manager and I tried to talk him out of it, because you couldn’t just suddenly change the policy on the regular clientele, but Mirra wanted the money.

“Tonight everybody gets charged a fin,” he said. “Everybody.”

He told the kid at the door to collect, and sent me over there to make sure everybody paid.

Customers complained, but they paid. Then three guys came to the door with three girls. “We don’t pay no charges,” one of them said. They started to elbow their way past the kid at the door.

I recognized the guys as wiseguys, friends of Mirra’s. But I felt like busting some balls. I stepped in front of them. “Everybody that comes in tonight pays five bucks,” I said.

“We don’t pay.”

“Then you don’t come in.”

“Who the fuck are you? Who you with?”

The question meant, What mob crew was I with? I played dumb. “I’m here by myself.”

“You know who I am?”

“I don’t wanna know. But if you’re some kind of big-time operator, you ought to be able to come up with thirty bucks for you and your girlfriends.”

“I wanna see Tony Mirra!”

“You wanna see Tony, give me five bucks, you can go right in and see him.”

Now the guys are very embarrassed in front of their girlfriends, and they start a ruckus, shouting and shoving. Mirra comes over.

“These guys don’t wanna pay the five bucks, Tony,” I say.

“Not these guys, you fucking idiot,” he says.

“Tony, I’m just doing what you told me to do. You didn’t say wiseguys come in free.”

“These guys get in.”

“You guys get in,” I say to the bunch, giving them a big smile.

“You’re a crazy bastard,” Mirra says to me.

With a guy like Mirra, you had to allow yourself a little fun every once in a while, otherwise you would go wacko.

I was sitting at the bar at Cecil’s. A friend of Mirra‘s, a guy I didn’t know well, came up behind me to pat me on the back and say hello. He ran his hand down my back.

“What the fuck you doing?” I said as softly as I could manage. He grunted and walked away. I knew what he was doing. He was checking me for a wire. I saw him talking to Mirra.

Later I was in the men’s room washing my hands. When I turned around, I bumped into this same guy. He quickly slid his hands down the sides of my jacket. I pushed him away. “I think you got the wrong guy, pal,” I said. I just left him standing there.

Nobody could get close to Mirra. The only family he was close to was his mother. You could never get him to talk about anything personal. One day you might ask him, “How’s your mother, Tony?” He might say, “Okay.” Another day you ask him, and he might answer, “What the fuck you so nosy about?”

He was always hustling broads. Women were attracted to him, even though he treated them like dirt. He was never married, but he had a load of girlfriends, everything from bimbos to movie stars. When he wasn’t hustling them, he was abusing them. He was just totally obnoxious. When a woman at Cecil’s complained that her umbrella had been stolen out of the coatroom, he said to her, “You think I care about a fucking umbrella? The thing for you to do about it is to get the fuck out of here and don’t come back.”

Then there was a time down at the South Street Seaport restoration project when one of the many street vendors, an old woman selling jewelry, was waiting to use the pay phone Mirra was tying up. Wiseguys spend their lives on the telephone. Mirra had been tying up the phone for about a half hour, making one call after another. When this old woman asked him politely if she could please use the phone, because that was the only phone in the area for the vendors to use, and they used it for business, Mirra said, “Listen, you fucking cunt, I’m using this phone. When I’m finished, I’m finished. Shut your fucking mouth or I’ll cut you.”

He was telling a bunch of guys about this very big movie actress he was seeing. “I got her to give me a blow job while another guy was fucking her and she was jerking off another guy,” he said. I must have winced or groaned or something, because he said to me, “Aw, what’s the difference? She was so strung out on dope, she didn’t know what she was doing. Don’t act like a fucking fruitcake.”

The Feast of San Gennaro is the biggest annual street festival in Little Italy, taking over Mulberry Street for two weeks in September. It’s a big tourist thing; people come from all over the country. It’s a religious festival, but on the street it’s all controlled by the mob. All five families are involved. Different captains each have a certain portion of a block that is his, where there may be five or six booths. You can’t just go to the church and say you want a booth at such-and-such a place. That is controlled by the mob captains. Anybody that puts a booth in your section has to kick back to you. The more powerful captains control the sections closer to the center of the feast. And captains control the supplies. One captain might have control of all the sausage that comes in, another controls the beer. In other words, if you have a booth and want to sell beer, you go to the captain or his representative and say you want beer at your booth. He’ll send a guy to you that will provide beer. So they get a cut of everything. You have to pay for the space the booth occupies, and you have to pay a certain amount off the top as a nightly fee.

During the Feast of San Gennaro everybody goes down and hangs around on the street, all the wiseguys. That’s the big thing to do. Eat food from the various carts. Some of the people with the carts and booths were itinerant carnival types, but a lot of them were neighborhood people that had had booths there for years.

The day before the feast began in 1977, Mirra had met this girl who had a merchandise stand at South Street Seaport adjacent to the Fulton Fish Market, and he was hustling her.

“I got her a slot at the feast,” he told me. “Drive me down there. I told her I’d help carry her stuff over to the feast this afternoon so she could set up.”

I drove him down to South Street. She was nice-looking and pleasant. But there was something about her. We helped her pack up and drove her to Mulberry Street.

Mirra says, “I’ll see you tonight, hon,” and we left.

I say, “How well you know that lady, Tony?”

“I just met her. I figure I’ll grab her tonight after the feast, spend a hot night.”

“You sure?”

“Who the fuck you talking to?” he says.

Later that night Tony took off for his date. I was in a coffee shop when he came stomping in.

“You knew she was a fucking lezzie!” he hollers. “And you didn’t tell me, you cocksucker! Son of a bitch. I went through all the trouble of getting her a booth at the feast. Know what I told her? I told her,

‘Don’t come back to that fucking booth tomorrow!’ “

Psychologists could probably have had a field day with Mirra. For my part, he was a dangerous and necessary pain in the ass. He got on me for not hustling broads myself, or bringing any around. I just said I had a girlfriend in Jersey and one in California, but I kept that part of my life separate.

Married mob guys typically have girlfriends. They’re not discreet about it. Other than that, there was much less skirt chasing than I expected. Women were always around and available, because they gravitated to these guys. Maybe they’d hook up with them later. But most evenings they just wanted to go out and have some drinks and talk over schemes with the other guys.

My personal rule was that under no circumstances would I have anything to do with any women hanging around the mob. Regardless of morality, that kind of thing will come back to haunt you when you testify in court against these guys. By saying I had a girlfriend someplace else, the heat was off me. Occasionally, just so I seemed normal, I would bring somebody around for dinner, a woman who I had maybe met in my neighborhood. I’d show her a nice evening with the mob guys, take her home and drop her off, and that was that.