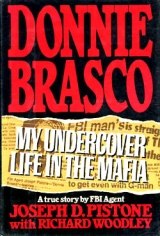

Текст книги "Donnie Brasco: My Undercover Life in the Mafia"

Автор книги: Joseph D. Pistone

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 13 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

10

THE ACCIDENT

I arrived at the airport that served my new home-town. My wife was not at the gate. I was met by another agent whom I knew only slightly. He said, “Your wife has been in an accident.” He said it was a head-on car crash; both drivers were women, similar in appearance except that one was younger. The younger one had been killed. He wasn’t sure which one that was. He said other stuff, but that’s all I remember.

We went to the hospital. My wife had not been killed. She was in intensive care, in critical condition, attached to machines and tubes. Her eyes were covered with bandages. Both her corneas had been lacerated. Her face was a web of gashes. She had a collapsed lung, a broken wrist, a broken collarbone. She was hooked up to a lung machine. She couldn’t see. She could barely talk. She squeezed my hand.

My daughters were there. The youngest, who was nine, had gotten sick at the sight of her mother and gone into the bathroom to throw up. I hugged the others, who were fifteen and thirteen, and tried to smile and act like everything was okay.

My wife told me that on her way to the airport a car coming toward her had veered out to pass another car stopped in that lane and hit her head-on. My wife climbed out of the car somehow and ran to the side of the road, afraid the cars were going to blow up. She heard bubbling in her chest, and as a nurse she knew that her lung was punctured. There were two women who had witnessed the accident. She asked if she could please lay her head down in the lap of one of them, because it would help her breathe. Her contact lenses had been smashed into her eyes. She thought she had lost at least one of her eyes. She told the women that in her car was a notebook and her husband’s flight number. She asked them to call the FBI and ask for an agent to pick me up at the airport and to call a friend’s house where the girls were staying. And then the ambulance came and she was brought to the hospital.

She was in terrible pain and scared. When I saw her, she didn’t know that the other driver was dead, and I couldn’t bring myself to tell her. Her friend Ginny was there. I went out in the hall. Later my wife said that Ginny had told her I was crying, and she said, “I told Ginny, ‘I’m sorry I missed that, I’ve never seen Joe cry.’ ”

I stayed with her at the hospital. My youngest daughter couldn’t bear to visit her because she was so mutilated. She sent notes instead.

The next day my two older daughters were leaving to drive home. My fifteen-year-old had just gotten her driver’s permit. Within sight of the hospital they were broadsided by another car that ran a stop sign. They were brought back to the emergency room by ambulance.

The nurses in the emergency room already knew them from their mother’s accident. The nurse called upstairs for me. I told my wife I was going to get a Coke and take a walk. In her condition I couldn’t tell her right then that the kids had been in an accident. But she knew something was wrong. “Why aren’t they coming to visit me tonight?” she asked. “They’ve got a lot of homework,” I said. “I told them to stay home.”

Our girls were not seriously hurt, just bruises and stitches. They were treated and released. My wife’s parents had flown in the night of her accident, and so were on hand to help take care of their injured grand-daughters as well.

I started thinking, What the hell’s going on here? What have I done wrong? I had been on this job since the summer of 1976. Now it is the summer of 1978. Two years and I haven’t been home two months. And everything could have been wiped out in the last two days.

I wish my circumstances allowed me to describe my family more completely, what they looked like, their relatives and friends, where we lived. At least to use their names.

Actually they changed their names—their last name. They dropped Pistone and adopted a new name. We never traveled under Pistone, anyway, and I used different names for everything, so it wasn’t such a big deal. Also, the girls had always been teased about their last name—Yellowrock, Wetstone, etc. So they were happy to be rid of Pistone. And my feeling was, they would probably eventually get married and change their last names, anyway.

But I used various names, just to make it a little more difficult for anybody ever to trace me. That got to be a pain for everybody but me. Sometimes my wife would get confused at an airline counter when she couldn’t remember which name she was supposed to be using that day. Or when she went to pick up things I had left at the cleaners, she often had to try several names before she came up with the one that I had left the clothes under.

My long absences were bothering my family more and more. “What kind of marriage is it,” my wife would say over the phone, “when the husband is never home?” The fact is, if we hadn’t had so strong a marriage, it probably wouldn’t have survived these years.

The way she coped with it was to develop a life of her own, even more independent of me—almost, she would say, as if she didn’t have a husband. It was not in her nature to brood or to feel sorry for herself. The family had moved to its present home only a few months before, and it had not been easy. My wife was recovering from major surgery she had undergone shortly before the move. And in the first weeks after the move, the kids were having trouble adjusting. They wouldn’t go to school. I offered advice, support, whatever, mostly over the phone. My wife dealt with it all on the scene. Friends included her in everything, with or without me. She encouraged our daughters to have kids over, and she cooked for bunches of teenagers all the time. She went out with our oldest daughter—just girls out on the town having a good time.

Her way of avoiding worry about me was to maintain a semblance of normalcy in the home. The hardest thing for her, she would tell me, was that when I went undercover, she had to start taking care of all the bills. That was the one thing she had never done, and she hated it.

She kept so occupied, she said, that she could go for long periods without ever thinking about being alone. Except that when I would call, she’d turn angry. Frustrations would pour out, sometimes in strange ways. She had focused so totally on the household that she would want to talk about that. The lawn mower wouldn’t start. The washing machine was broken. I’ve only got five minutes to talk, I would say, I don’t want to talk about that stuff. “To me,” she would say, “this is the real stuff, right here at home. I can’t see any further right now than what’s bothering me here.” Sometimes we would yell at each other.

The telephone became our link, our lifeline. When I called, I wanted to talk to everybody in turn. My wife always filled me in on everything that was going on with the kids. That was important. Often there were problems—school, discipline, personal—and my wife would tell me about them over the telephone and I’d try to straighten things out. But more often than not, I couldn’t straighten things out over the telephone. There’d be crying and screaming and everything. Everybody would be upset, and all I could do was put my two cents in. The kids were upset that I was away so much. I couldn’t defend myself very well, except to say that I had a job to do. Their mother would try to make them understand about my dedication to the job. What did they care about how dedicated I was? They were kids. They wanted their father home.

Sometimes when frustrations got bad, my wife would holler at me something like, “Either get out of this job or I’m getting divorced.” She never meant it. I knew that. But the kids didn’t know that, and sometimes they overheard it.

My youngest daughter sometimes pretended that we were divorced. Some of her friends had divorced parents. So she would play this game in her mind that she was a kid from a broken home. Somehow that made it easier for her to get along during some of the tough times, especially when they moved into a new area.

Then when I did come home, they would resent me. My wife said to me, “I get so excited when you’re coming home, I really can’t wait. Then when you get here, I get furious. It’s bad enough you being gone for long periods of time. But then when you come home, you want to run the show again. You’re home a couple of hours and you want to become boss. You want to run the show. But I’m running it. I’m used to doing things my own way around here.”

I couldn’t help walking into the house and wanting to be the head of the household, and she couldn’t help her resentments of that. Sometimes it would take us a couple of days to get reacclimated to each other. A lot of the times we didn’t have two days. Sometimes we had only one. Sometimes we had half a day or just a night. She clung to her own system, and I was sometimes an outsider. She found herself even resenting having me crowd her in her bed. So she bought a king-size bed to be able to sprawl like she was used to.

As the girls were growing up, they had more outside activities. I would get home to find one or two or all of them going out. I would say, “Aren’t you going to stay home with me?”

They would say, “You never stay home with us.” Or, “We can’t count on you being here, so we can’t make appointments around you, Dad.”

Sometimes I would get home for a day and would have to leave the next morning before they were up. I didn’t always say when I was going. My youngest daughter cried when I got home and cried when I left.

I had frustrations too. If I came home for a day and a night and found out there was a problem, I would have to try to straighten things out instantly—there was no time to take time. I would try to make rules. My daughters would tell me that I was like a visitor and had no right to make rules. Sometimes I just seemed to get on people’s nerves.

Over time the girls developed the habit of going to their mother with everything they wanted to talk about. They went to her first. They told her everything. As understandable as that was, it hurt me.

They came more and more to resent the job, and the FBI. “What you’re doing is not a job for a married man with a family,” my wife would say. “They don’t care about us. They don’t care about you.”

My wife was in the hospital for eleven days. And then when she came home, she was nearly helpless. For a long time she couldn’t see well. She had to wear special dark glasses, and even a satin sleep mask at night, because light was agony to her eyes. There were still pieces of glass embedded under her skin. She would need plastic surgery, but first she would have to heal for a year. The cast on her arm allowed her fingers to move. But sometimes when she was holding something, like a cup or a glass, it would just suddenly drop from her hand. Things like that would bother her.

My wife was always self-reliant, energetic, optimistic. She was athletic, always playing tennis, doing aer obics, on the go. She was always doing things for everybody else. And now, suddenly, she couldn’t do things for herself. Her spirits were down. I wouldn’t say she was depressed. In the thirty years I’ve known her I’ve never seen her depressed. But now she was down, not able to do ordinary things.

For the first time our daughters saw her in this almost helpless state. They started getting on me harder about not being home more. I wanted to be home more. But what could I say?

When my wife came home from the hospital, I stayed one more week. We all had a pretty good time, given the circumstances. It was the most time we had all spent together in years. We had outdoor barbecues and everything. I had fun with the girls. It was going to take a while for my wife to heal. Her eyes were still extremely sensitive to light, so she had to keep them covered most of the time. But at least we were together.

My wife is basically a pretty understanding person. But this was a bad time. She wanted me to quit the undercover job. I could see her point of view. It had come up before: “You’re just away too much at one time. It wouldn’t be too bad if you were gone a day or two, but you’re gone three weeks at a time, then you come home for one or two days.”

But I had come too far. By now, quitting wouldn’t involve just me. I had brought Lefty around to other operations, and the people running those operations were depending on me to keep their operations going. If I backed out now, a lot of people would be left holding the bag. Quitting was something I couldn’t do.

She knew I was working with the mob. I gave her a few more details, some of the circumstances in Milwaukee, to try to ease the tension a little bit, to show that my being away weeks at a time couldn’t be helped. She knew of Tony Conte because she had talked with him on the phone a few times. I explained to her that if I pulled out, Lefty and the others in New York would stop working with Conte.

I didn’t talk to anybody else about these concerns. Nobody. Because nobody else but me was going to make the decision to leave the job or stay. I didn’t feel it concerned anybody else. No matter what anybody said to me, the decision was going to be mine. I had to stay on the job.

I was in touch with Lefty throughout this time, by telephone. I had left a California “hello phone” number where supposedly he could reach me. He left messages, I called him back.

I told him my girlfriend was fine and that everything ought to get moving again in Milwaukee after the Fourth of July holidays.

He was busy spreading Tony Conte’s money around and trying to arrange for a sitdown with the Milwaukee mob. Mike Sabella was entertaining people. Sabella had borrowed $200,000 for a major renovation of CaSa Bella, but the contractor had quit on him. “He’s in trouble there,” Lefty said, “that cocksucker contractor.”

One day he said to me, “You see that David Suskind Show last night? They had two informers, you know, paid by the government. On TV. You know, guys that already cooperated, and now the government gave them a different identification and put them out there. They said they got 2,250 informers and half of them are in the San Diego and L.A. area.”

“Wow.”

“So these guys, some guy that’s writing a book accidentally cracked it out about them. So now they’re ratted out, and guys are looking to get rid of all these guys.”

“Whack ‘em out, right?”

“Yup. They don’t give a fuck, the government. So these two stool pigeons say anybody that becomes a government informer is fucking crazy. Unbelievable. How’s your girl?”

Over a period of time I got so I could understand just about everything Lefty said. Two guys in the federal Witness Protection Program had been accidentally exposed, so now they had bared their resentments about the government’s carelessness over TV, and that the mob was looking for all these protected informants.

“My girl’s good. Everything’s all right.”

“Why can’t your girl come into New York or Milwaukee with you?”

“She’s working. She don’t get vacation now.”

“Well, you gotta get back out there and get the groundwork. And once you get that, you’re gonna stay there a long time.”

“Yeah, I know. We gotta start making some ends out there. When are you going out there, after the Fourth?”

“When I’m gonna get out there, I don’t know. I’m feuding with the wife now. We had a fight about she wants to go away somewhere for a vacation. I gotta go reach out for people for late this afternoon. Tonight I got an appointment. Tomorrow night I got an appointment. I got meetings in Philadelphia.”

“Mike likes this Milwaukee deal, right?”

“Right. No question about it. I’ll tell you something: Everything’s green lights.”

Lefty had been given the full go-ahead by a message from Carmine Galante in prison. While he was arranging for the sitdown, I went back to Milwaukee. For the first couple of days I didn’t tell Lefty because I wanted some time with Conte to go over things without having to account to Lefty for every minute of every day. Then Conte and I hit some more spots, trying to place machines, and again ran into a stone wall. But we were gathering evidence of the case, and by being seen by more and more people, we were establishing more credibility as guys trying to hustle a buck. We were also insuring that word got back to the Balistrieri people that we were out there pushing a vending-machine business.

We made a visit to Pioneer Sales and Service, a vending-machine wholesaler in Menomonee Falls, to look over the various machines available. Along with Conte and me was Conte’s “employee” that he had told Lefty about. The “employee” was another undercover agent who went by the name of Steve Greca. Conte told the president of the company that he wanted to buy machines for distribution in the Milwaukee area, and that he would also be interested in purchasing any vending routes that became available. He told him that Best Vending was a serious, licensed operation, not fly-by-night, and he showed the guy the city and state licenses for the business. The president said he would be happy to cooperate with Best Vending, and he gave us a tour of the place, showing us the various machines, and handed us a mess of brochures.

Just to give the impression that we were moving the business along, I called Lefty and told him that Conte had ordered some machines—when in fact he hadn’t.

The mob blew up a guy in Milwaukee. Somebody put a bomb under the car of a guy named Augie Palmisano. The murder was in the newspapers, plus our people came up with some information about it. Palmisano was with the Balistrieri family, and the mob suspected he was an informant. The word was that guys were starting to put remote-controlled starters in their cars.

The killing made Conte and me a little nervous.

Lefty called and told Conte, “I got a meeting tonight with those people from Chicago at my man’s place. We reached out, you know. I might have to fly out there later to get a proper introduction. That’s the way they do it. We didn’t sleep on this thing. I’ve been with people every day. But everything is fine. No problems whatsoever.”

“I’m glad to hear that,” Conte says, “because they’re playing kind of rough around here. Did Donnie tell you about they’re blowing guys up here?”

“Forget about it,” Lefty says. “Doesn’t mean shit. They’re blowing guys up because they done something wrong.”

“Yeah, but I wanna make sure I don’t do nothing wrong.”

“You’re not doing nothing wrong.”

“Okay.”

“Let me tell you something,” Lefty says. “Once you start rolling, I’ll be there with you for the first ten days. When I get it set up and I come out to Chicago, you gotta meet the people. Understand? Once I get the proper introduction, I’ll have dinner with you and them. There’s no problem over here. We’re in like Flynn. Put Donnie on the phone.”

I take the phone.

“Donnie,” he says, “he didn’t sound too enthused what we’re doing here. He’s worried about people bombing out there.”

“He’s enthused, but he’s nervous. He doesn’t know what’s going on.”

“I don’t blame him for being nervous,” Lefty says. “But that’s got nothing to do with us. The guy might have been a stool pigeon. The guy could have been anything. Tell him not to worry about anything. And to keep near that beeper, because I might have to reach him anytime now, now things are moving.”

“Donnie, is Tony there with you?”

“Yeah, Lefty.”

“Tell Tony, where’s Rockford?”

“Rockford, Illinois?”

“Yeah. ”

I ask Conte where Rockford is. “He says it’s about ten miles outside of Chicago, Left. Why?”

“Some people are making some phone calls and I got to go out there, to see people out there. They will set up an appointment for me. I gotta wait for a call. He’s gonna make a call to this place Rockford, wherever that is. He’s gonna give my name and when I’m coming out. And I gotta lay the cards on the table what I’m doing there. That’s the whole thing in a nutshell. Mike entertained six of them last week. He didn’t give me the bill. He ain’t worried about it.”

“Everything at Mike’s went all right?”

“Everything is perfect. The guy kissed me on both cheeks. We can do anything. I stood with them about an hour and a half, then I excused myself. Because Mike was still with them. They were bullshitting about old times. Tell Tony to keep near the beeper.”

A guy had a pizza joint next door to Lefty’s social club. Lefty decided he didn’t like him anymore, so he beat him up and threw him off the street. The guy was an ordinary citizen, and he now wanted $2,000 cash for damages. Lefty said if he didn’t come up with the money, the guy would press charges and Lefty could face six months in the can. Mike Sabella thought Lefty should take over the joint and make it his own pizza parlor. Also, Lefty was still getting muscled over the jam his son got into when he tried to rob a guy for diamonds and the guy turned out to be connected. They were leaning on him for $3,500 more.

So, while pushing the matter of the sitdown on Milwaukee, Lefty was poor-mouthing as always.

“Some people wanna meet me tomorrow at Newark Airport,” Lefty told Conte over the phone, never giving Conte as much information as he would give me, his partner. “Here’s the situation now. You see, we’re broke. I have no goddamn money. You understand? Now I got to entertain these people. I ain’t even got a car to get out there tomorrow. And then I gotta come out there where you are by plane. You gotta get me a reservation. Now, I gotta see if I can scheme tomorrow morning for some bread someplace and a car to get there. And when I do come out where you are, you gotta meet me and we’ll go see these people out there, because they’re gonna have to know you better than they know me. Because you’re representing me. Understand?”

“Yeah.”

“But the question is, I got exactly twenty-three bucks in my pocket. How the fuck do I get out there tomorrow?”

“Maybe we could do a car-rental deal,” Conte said, stringing him out.

“This guy tomorrow is giving us names. Bosses. They’re the main guys, you know. They’re looking to help our situation over there. One hand washes the other. I gotta entertain this guy all day. The guy is eighty-one years old. He’s a heavyweight. The guy owns hotels out there at Newark Airport. How do I entertain these people all day with twenty-three bucks?”

“Well, I’ll have to send you some bread,” Conte says finally.

“Yeah, but I’m embarrassed because Donnie says you don’t feel too enthused about all this here, how we’re breaking our ass over here.”

“Hey, I never said I wasn’t enthused. Certainly I’m enthused.” “

“Let me tell you something. That’s why I got mad at Donnie. Guy’s a jerk-off. Says you weren’t enthused. I says, ‘Don’t you think he’s gonna meet these people?’ Because when you see these people, forget about it. And you’re gonna sit down with these people with me.”

“I don’t want nothing to happen to me,” Conte says. “I do what you tell me, right?”

“Right. There’s no problem. Where is Donnie now?”

“He’s out.”

“I don’t understand this frigging guy. He’s out. See, the question is, if Donnie wasn’t gonna do nothing out there with you, he shoulda been in with me. Now he could run around with me. But here I’m stranded by myself.” “

“I’ll send you a grand in the morning, Western Union.”

“Make it as early as possible. And tell that guy Donnie not to do nothing but stay by you. I will definitely have to come right out there after I see these people tomorrow. You’re gonna sit down with these people and me. We’re gonna entertain them people, you and I and Donnie. Take them to dinner. We’ll get everything straight. And everything that you listen to, you know from the ground floor in. Everything that’s going on. And we got no problem. You stay by that beep. The first beep you get from New York, I’ll tell you what plane I’m taking and everything.”

The man he was to meet at a motel near Newark Airport was Tony Riela, an aging Bonanno captain with contacts to Chicago. It was Riela that had kissed him on both cheeks at CaSa Bella. The understanding was, Riela would make the calls to Chicago to set up a meeting. The Chicago people would call people in Rockford. And those people would make the introductions to Balistrieri in Milwaukee.

Lefty had a successful meeting in Newark. The day after, he called to announce that he was coming to Milwaukee for the sitdown. It was now July 24. More than a month had gone by so far in arranging for the meet. He gave Conte the flight information and told him to write it all down. “Get me that same room in that same Best Western, right? Them people come from right in that town. I’ll explain everything when I see you. Where’s Donnie?”

Conte hands me the phone.

“He wrote everything down?” Lefty says.

“Yeah, he got it all.”

“Listen to me carefully.”

“I’m listening.”

“Don’t let it go any further.”

“Okay.”

“I got me a sitdown with the two main guys in that town where you are now. I can’t get no names until I get out there. When I get there, I gotta make a phone call back into New York at six o‘clock, tell them where I am, what room number. They call the Chicago guy. He’s gonna come and pick me up. They’re gonna take me away. They’re gonna talk to me. And they’re gonna check this guy out completely.”

“Okay.”

“I hope he’s all right.”

“Yeah, Tony’s all right.”

“I mean, I don’t wanna get him scared by saying that, and I representing him.”

“Right.”

“They wanted to know if he was a local guy. I said, definitely a local guy.”

“Yeah.”

“Now, once they call me, I’ll be on standby there. When I call New York and they call back, it might take a day, might take two hours. In other words, I cannot move away from that room. We’ll have to eat and drink and sleep there. Understand?”

“Yeah, we wait.”

“They’ll send representatives down to pick me up and they’ll take me to go with these people. We all go—me, you, and him. But I go into a separate room with them for the first conversation at the table. I represent the situation. They cause him a table. When everything is all right, then I call him in, I introduce them after the first conversation.”

“Okay.”

“Now, the money he sent me. I went for already five hundred on my phone. My plane I’m taking first-class is two-hundred-thirty something. And we gotta entertain them people after I get through introducing them. And I dropped two-fifty at the Newark Airport, with all them people. Because it took me four hours. But I ain’t worried about that. The most important thing is that the main one comes from that town and everything is beautiful. Not to go further. But they told me, I sit down with them alone. And then they’re gonna check him out. So as long as we got a peace of mind there.”

“Yeah, there’s no problem with Tony.”

“Good enough.”

Lefty flew out. We went to our room at the Midway Motor Lodge. Lefty called New York and told them what room he was in. New York was to call the Chicago-Rockford people and tell them what room Lefty was in. Then somebody would call and say they were on the way to pick us up. We just had to sit and wait for the phone call.

Lefty had said we might end up waiting any amount of time, even days. That’s what happened. We couldn’t leave the hotel. Conte came to hang around with us during the day. We had a first-floor room. We sat around the indoor pool. We played cards. We shot the breeze. We ate breakfast, lunch, dinner. At night we hung around the lounge and listened to the band.

Lefty briefed Conte on the upcoming sitdown. Conte now belonged to the Bonannos, so the Milwaukee boss couldn’t steal him or the vending plans. The options the Milwaukee boss had were: yes, you can stay and do what you want; yes, you can stay and I’m your partner; or no, I don’t want you here. The Bonannos had to abide by his decision.

“I tell them that you’re out of Baltimore, you’re here three years. I know you from Baltimore. You’re going into a pinball business. You’re buying a route. You won’t disrespect nobody. I’m involved in it, my money. You’re like our representative out here. We don’t want no problems. Because we can handle our own problems. You open the doors for us, we appreciate it, and if you got somebody’s relative that wants to come in with us, most likely they will. That’s all. Like Mike, my man, says, ‘Short and sweet.’ ”

“I just tell them that some of it’s your money and some of it’s my money?”

“You don’t tell him anything. You don’t do no talking. ”

“I meant if they ask.”

“No, they don’t ask you nothing. They can’t ask you. They have no right to ask you. They take my word for everything I say to them. Because I’m not asking them to put nothing up.”

“I’ll be glad when this is over,” Conte says.

“Sure, you’ll have peace of mind.”

One day went by. Two days. Just sitting and waiting. I thought, What the hell am I doing here? My wife is home trying to cope with recovering while I’m sitting around a damn motel twiddling my thumbs. Finally on the third day I said, “Left, I’m not sitting around here any more waiting for this phone call. We might be waiting another week. I gotta get back and see my girl. She’s not doing too good.”

“What are you talking about?” he snaps. “We gotta wait for this here. I thought you said your girl was working.” “

“She was, but she had a relapse. I’ll just shoot out there for a day or so, then shoot right back here.”

“What the fuck are you talking about, Donnie? This is the most important thing we got right here. We got a sitdown coming up. You’re putting your girl before what we got here.”

“Hey, Left, I gotta. She’s got nobody out there, she’s in bad shape. Just a day or two, I’ll come right back.” “

“Unbelievable, you put her first. That’s the trouble with you, Donnie. You fucking take off anytime you feel like it. She ain’t gonna die. What are you worrying about?”

That really ticked me off. I flew home.

The next day they got the call.

Three guys came to pick them up: Joe Zito, the old man from Rockford who was the main contact, and two guys named Charlie and Phil. They had Conte and Lefty follow them downtown to a dinner theater named Center Stage, which was owned by Frank Balistrieri. There they were introduced to Frank’s brother, Peter, and Steve DiSalvo, who was Frank’s right-hand man. Then to drive to the sitdown, Conte suggested that the Rockford guys ride with him and Lefty. They followed Peter and Steve to Snug’s Restaurant, in the Shorecrest Hotel on North Prospect. These, too, were Frank’s places.