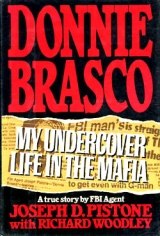

Текст книги "Donnie Brasco: My Undercover Life in the Mafia"

Автор книги: Joseph D. Pistone

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 20 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

Doctors and professional people were the best targets, he said, because they were always looking for ways to invest their cash. Lately his most prominent victims had been chiropractors. He had pled guilty so that other “family” members wouldn’t be hauled into court to testify.

Rossi and I stayed in the apartment with Sonny and John. At about two A.M., we were all getting ready to go to bed. Rossi comes out of the john in his Jockey shorts. Sonny starts rolling on the floor laughing. “Holy underwears!” he spouts whenever he can get a breath. “Holy underwears!” Rossi’s Jockey shorts have holes in the back. Sonny can’t control himself. “Wearing two hundred dollar slacks, hundred dollar shirts, two hundred dollar shoes, and you got fucking underwear on since you were in high school! Holy fucking underwears!”

Two days later Nicky Santora reported that he had found our marijuana price of $270 to be too high. But he said that he could do business if our source would “front” 200 pounds and wait for payment for a week.

When we went back to Florida, we contacted our source and told him the grass hadn’t checked out to be as good as he said, and that the only way our people would buy it was if they would front 300 pounds and wait two weeks for payment. The guy had to think it over.

The next time Sonny came to Florida, he brought news of a shake-up in the Commission. “They knocked down Funzi Tieri,” he tells me. He said the power was now Paul Castellano, Neil Dellacroce, and Joe Gallo—the top guns of the Gambino family. “They were given the power and are handling it properly,” he says. “I met with Paulie the other day. I did him a big favor which nobody else could do. Paulie has an alliance now with the old man here.” He meant Trafficante.

He didn’t tell me what the favor was. But the Gambinos were big in the drug business. In any case, Sonny was indicating that he was now in tight with the new boss of bosses.

He was waiting for Santo Trafficante to come to the motel. Trafficante arrived, and they went to Sonny’s room. Permitted by a court order, we had his room bugged. But right away they turned up the TV volume to cover their conversation.

Sonny and I were having dinner alone. Sonny didn’t wear a lot of jewelry or anything flamboyant, but he did have some nice rings. If he had a gold buckle on his belt, he would wear gold; with a silver buckle, white gold. It is common for wiseguys to wear pinkie rings. But he had one that I really liked, a white-gold horseshoe with tiny diamonds in it. I loved that ring. It was his favorite too.

“Sonny, one of these days I’m gonna get a ring like that.”

“Like what?”

“That diamond horseshoe ring. I really like that ring. I always wanted one like that. But they’re too expensive, and I never could get one in a score. One day I’ll get lucky.”

“You like it? You just got lucky. Here.” He slid the ring off his finger and put it down by my hand. “It’s yours.”

“Hey, Sonny, I can’t take that from you.”

“Why not? You like it, you got it.”

I really couldn’t take it from him. I couldn’t accept an expensive gift like that in my position. I would have to log it and turn it in just like any other evidence; otherwise, I would compromise myself in the investigation. I guess I could have taken it and then given it back when the operation was over, but if it got lost, or Sonny got whacked or something before, it would really bother me to have accepted it.

I didn’t want to offend him, either, because he did it from the heart. He would do things like that, never make a big deal out of it. “I really appreciate it because I know how much you like that ring.” I pushed it back across the table with my fingers. “I can’t take it, but thanks.”

He shrugged and slipped it back on his pinkie.

The next afternoon we’re in the coffee shop at the Tahitian.

“I feel strong today,” he says.

“So? What does that mean?”

“I feel strong enough to beat you at arm wrestling.”

“Sonny, you never beat me. What’s gonna make today any different?”

“How strong I am. Come on.”

“In here?”

“Come on.”

We put our elbows up on the table and go through all the gyrations of getting ready, lock our hands in.

“You ready?” He looks me in the eye.

“Yeah.” “

“I’m gonna beat you.”

“Go ahead.”

“Go!”

We strain our arms together. Then he spits in my face, I flinch, and he slams my hand down.

“I didn’t tell you how I was gonna beat you.”

Sonny had a scheme. You couldn’t get really good Italian bread anywhere in the area. We asked around why that was, why the bread was so much better in New York. Nobody knew. We asked a baker, an Italian guy from New York.

“The water,” he says. “The water in the New York area is the best there is. It’s crucial. Something to do with how the yeast reacts. That’s why you can’t bake Italian bread that good anyplace else in the country.”

Next thing I know, Sonny had set up a deal with this guy. He’s going to bake for us. Sonny is going to get a fleet of tanker trucks, like those that deliver milk, and truck New York water down to Florida and have this guy bake our Italian bread and make a fortune.

Tony Mirra got out of prison. When he was in the can, guys kept reporting to Lefty that Mirra was calling people and was pissed off because he heard that Lefty and I had made a ton of money in Milwaukee and were making a ton of money in Florida, and some of that should be his because he brought me around to the crew in the first place.

Lefty tells me, “I told him, ‘You better have friends when you come out.’ I says, ‘You better stop knocking people, knocking their brains out.’ ”

When I was alone with Sonny at the Tahitian, he says, “I gotta ask you something, Donnie. Is Rocky a wire?”

“Hey, Sonny, I been dealing with him for over six years without any problems, and I been using him to buy and sell merchandise. No problems. That’s all I can say.”

“Well, Mirra branded him a wire. But, of course, that’s Mirra’s style.”

Lefty had a lion. Some guy who raised animals in New Jersey gave Lefty a little cub. Lefty loved it. He took it with him when he drove around in the car. He kept it at the Motion Lounge, and we played with it. It was a nice little pet. Lefty never gave it a name. We just called it “lion.” It stayed in the front of the club at the bar. We also had a regular house cat that stayed in the back.

After a couple of months the lion was growing into a real lion. It started leaving claw marks on the leather seats of Lefty’s car, so he couldn’t drive around with it anymore. It clawed you when you played with it. It got to be the size of a large dog. Pretty soon we couldn’t even take it out for its usual walks. It stayed at the club during the day, but it couldn’t be left there all night anymore. Sonny’s cousin, Carmine, owned an empty warehouse not far away from the Motion Lounge, so Lefty would take the lion over there every night in a van. Guys would go there every day and feed it. It was costing around $200 a day to feed, because the guys were giving it prime steaks.

I was on the phone from King’s Court one day, talking to Boobie at the Motion Lounge. “Lefty’s across the street loading the lion in the truck,” Boobie says. “We got to get the lion out from under the bar. Somebody ratted him out. It could cost us a $10,000 fine.”

Somebody in the neighborhood had spotted the lion in the club and called the police. By the time the police came, Lefty had taken the lion to the warehouse. What the cops found was the house cat sleeping on the pool table in the back room.

The cop says to Charlie the bartender, “I’m talking about a lion.”

“What we got is that cat,” Charlie says. “If we got a lion, that’s it.”

After that, the lion had to stay full-time at the warehouse.

Lefty called me in Florida. “We gotta get rid of the lion. It’s tearing up the walls in the warehouse. It eats the wires. How about you take it down there? You got five acres. Just put a chain-link fence over one of the tennis courts. We’ll ship it down.”

“You’re crazy. They’re not gonna let us keep a lion in a tennis court.”

One night they loaded the lion into the van and took it to a park in Queens and tied it by its leash to a bench.

Lefty called me. “Get today’s Post. They found our lion. It escaped. They got it at the ASPCA. That lion is making some news. It’s all over television. Pretty bastard.”

The front page of the New York Post had the headline: KING OF THE JUNGLE FOUND IN QUEENS! A big picture showed the lion between two cops, one holding its leash. The story said that a man had found this six-month-old lion cub wandering outside St. Mary’s Cemetery in Flushing, Queens. Nobody had the slightest idea where the lion had come from.

Some of Sonny’s crew in Brooklyn were arrested, and it looked like there was a snitch involved. Lefty called to tell me everybody new was suspect.

“In other words,” he tell me over the phone, “who’s responsible has to die.”

“They’re not worried about Tony, are they?”

“Let’s put it this way: You’re not, I’m not, but they are. We gotta go to his background.”

“Okay.”

“We got Rocky around us. And what’s that guy?”

“Eddie.”

“Eddie, yeah. And we got Chico, right?”

“Well, Chico had another argument with his girl, and he took off.” Agent Chico had left the operation.

“I don’t like that. You see, that’s another thing I gotta check out there. That’s another thing that’s no good.”

“Well, this broad is driving him crazy.”

“I understand that, but it’s no good. You’re involved in all these things. I can’t account for everything. Like now, they’re letting it slide about Rocky out there.”

Rocky, the undercover cop I had helped introduce into the mob world for a separate operation, the one who had gone on the boat trip with us, had a car business not far from New York City. I helped Rocky set up this business as a cover. When Tony Mirra got out of prison, he started hanging out with Rocky. That put Lefty in a bind. Since I had introduced Rocky to him, Lefty felt that Rocky belonged to him and owed him a share of anything he did. At the same time, Lefty didn’t want to have anything to do with Mirra.

“He’s hanging out with that stool pigeon,” Lefty says, meaning Mirra. “I don’t know what you’re gonna do with him. I don’t know what’s going on. This guy does something wrong, Donnie, you and I are going bye-bye. I know this guy is gonna send us to our death. I gotta talk to you about it.”

It put me in a bind, too, because I didn’t know what was going on with Rocky and Mirra, either.

“We’re coming out tomorrow,” Lefty says over the phone, a few days before Thanksgiving. “Four guys.”

“Who’s coming?”

“You gotta pick us up. He’s gonna tell you that there.” He gave me the flight information to write down and said that “he,” meaning Sonny, was going to be calling me about this. “Four people. Don’t ask no questions.”

“Okay. All right. Uh, these guys heavyweights, or what?”

“Look, leave it alone. Just get us a couple of rooms. You gotta get us a car. Get a big four-door job. Charge it to our expense on the business.”

“Okay.”

“Double rooms next to each other, by the pool.”

A few hours later Sonny called.

“Look, a couple of people are gonna come down there. They need the car. And only if Boobie asks you for anything, whatever you want, you give him, and then I’ll make it up.”

“Yeah, okay.”

“Only him.”

“All right.”

“They’ll explain to you down there.”

“I was just talking to Lefty,” I say, “and he said that you wanted to talk to me about some people coming down. You don’t have any information, though, huh?”

“Tomorrow.”

Then I called Lefty back—I kept both of them clued in to cover myself. “I just talked to him,” I say, “and he said Boobie and a couple of other guys would be coming down.”

“He didn’t mention my name? I don’t know what’s on this fucking man’s fucking mind. That’s all he told you—Boobie’s coming down with a couple of guys tomorrow. And he never mentioned my name.”

“Not right off the bat, but I said I had talked to you—see, I don’t want to mention anybody’s name.”

“Right, there’s no names involved. We always doing everything right. And we can’t embarrass ourselves, that’s what counts, that’s the goddamn thing. Now, we’re not gonna tie you guys up, you understand?”

“Yeah. We’ll just give you the car, you do what you gotta do.”

“We’ll come back, party it up, a few drinks.”

“You’re not gonna do nothing tomorrow night, right?”

“No, no, we’re gonna just have a few drinks together. And expect us back in the future. I’ll explain to you when I see you.”

The next night, Rossi and I were to pick them up at the Tampa airport. We were trying to hold expenses down, especially where Lefty was concerned. I told Rossi that I wasn’t going to put out any money to rent them a car. They could rent their own car.

We met Lefty, Boobie, an ex-New York cop named Dennis, and Jimmy Legs—James Episcopia—a big guy abut 6’4”, with skinny arms and skinny legs and a pot-belly and a toupee.

Lefty says, “You rent a car?”

“No, my American Express line is used up. I’m overextended.”

“Well, who the fuck’s gonna rent the car?”

“Put it on your fucking card for once. Why should I get stuck with the bill? I don’t even know why the fuck you’re here.”

Then we went to the baggage claim. I didn’t pick up his bag as I always had. Everybody else got their bags, and his was still riding around. Finally he got the idea and picked up his own bag.

This happened in front of these other wiseguys, and he was very steamed. I was really going to hear about this when we were alone, but I didn’t care. I was tired of Lefty.

There were times I could sit and talk enjoyably with Lefty, largely because of the genuine affection he had for me. Then there were times I could have strangled him on the spot because he embarrassed me or treated me like a piece of shit. Like, we might be at a Chinese restaurant and I’m ordering something that’s not Chinese. And in front of everybody he would talk about what a fucking nitwit idiot I was. I knew this wasn’t personal. He was like that with everybody. But I couldn’t swallow everything all the time.

Back at the end of 1979, I had blown up at him over something. “I ain’t your fucking slave,” I had said.

“So when we’re out, don’t you fucking embarrass me in front of people because I might lose my head and fucking whack you, and that’s bad for me because then I get killed.”

“But see, Donnie, you don’t understand,” he had said. “What I’m trying to do is to school you. You never hear me talk to Mike Sabella that way. Suppose Mike heard you talk like that? When they open the books, they won’t put you up. Don’t you want to be a wiseguy?”

So now, we got to the rental car ahead of the others, and he blew.

“You fucking embarrassed me in front of my friends, you cocksucker!”

“You don’t like it, huh? Now you know how I feel when you embarrass me. Now I’m schooling you in my thoughts. I’m not a fucking peon anymore. I’ve made a lot of fucking money for everybody. I’m entitled to the same respect.”

“Don’t you think these guys noticed? Don’t you think they’re gonna go back and tell Sonny? Don’t you think that’s a black mark on you?”

“I would never embarrass Sonny, because he’s a fucking boss. But, hey, if that’s the way the fucking game’s played, then that’s the way it’s played.”

He sighed. “Six fucking years and you still don’t know nothing.”

Dennis the ex-cop and Jimmy Legs joined us in that car. Boobie rode with Rossi.

On the way to the Tahitian, Boobie asked Rossi, “How many guns do you have?”

“Three.”

“Good, except I don’t want any small guns like .25s.”

“I’ve got .32 automatics.”

“Those are okay. We aren’t going to do anything now. We’re just looking things over and running time tests, learning the streets in St. Petersburg. We’ll be back next week to do this job if everything works out.”

Time tests related to casing a job—the time it takes to pull something off, to get there and get out.

That night we sat at the King’s Court until maybe five A.M., bullshitting, laughing. We talked about everything from the difficulty of hiring reliable waitresses, to the prime lending rate at banks, to the value of education.

Jimmy Legs says, “When I was up in Canada doing some work guarding the Old Man, I had a lot of time on my hands, so I decided to take some philosophy courses at the college up there.”

Boobie asked Rossi how it was going with the fugazy jewelry he had brought down from Sonny’s cousin, Carmine. We had it on display for sale. Rossi said that some of the less expensive items sold okay, but some of the heavier stuff wasn’t going to go. He sold a “Rolex” watch to one of the waitresses. “It’s a good-looking watch,” Rossi says, “but it turned her arm green.”

Lefty says privately, “Donnie, I can’t tell you about this job because it’s not my score. But when we’re ready to do it, I’ll let you know what it is. We’re probably going to use your apartment to stash the loot and maybe to hole up in.”

The next morning, the four of them took off in the big car. A surveillance team followed them to the St. Petersburg area but lost them in the vicinity of Route 19 and Forty-ninth Street.

That night, the seven of us went to a Greek nightclub in Tarpon Springs where they had belly dancers. The girls were dancing around our table, and the guys were putting $5 and $10 bills in their bras and panties.

The guys started debating about who was the best-looking guy, which of us the girls would go for. Boobie slapped a $100 bill to his forehead, where it stuck, and said, “This is the best-looking guy.”

The following day, the surveillance team stayed with them to Pinellas Park, just outside St. Pete. The agents watched them case the LandmarkTrust Bank. That bank is only a block from police headquarters.

Later that day, Lefty said they had decided against the score. “Things didn’t look right,” he says.

Behind the scenes, Rossi and I were dealing with one of the primary frustrations of working undercover. We couldn’t get clear authorization to give these guys the guns if it came to that.

We often had difficulty getting decisions fast enough from Headquarters on what we could and couldn’t do.

On the street you have to make decisions on the spot, often during conversations with a badguy. That’s normal, an everyday part of undercover work. But we might need an authorization for something from Headquarters in a day, and it takes two weeks. Part of the reason for this was that we were asking for authorizations in legally sensitive, potentially controversial areas where things weren’t black-and-white.

But these were crucial situations for our investigations. Often they were life-and-death situations. With myself and most of the undercover agents I talked to in the course of my whole career, the greatest frustration was that they couldn’t get an answer when they needed it.

You get a deal worked out with the badguys. You ask Headquarters: “Can I do this?” Nobody wants to say yes or no, so it gets drawn out. So that puts you in the position of having to draw out your story for the badguys, keep them on the line.

You might request money or approval to make a buy. You can string a buy out for a couple of days, that’s no big deal. But you can’t string it out for a month. If you go weeks with excuses, that knocks down your credibility—especially if at the end of that time you can’t go through with the deal. If you pull that two or three times, it gets old. The badguys are going to think, This guy’s got no power, he’s not worth dealing with. Word gets around the street that you’re a bullshitter. Or maybe you’re a snitch.

Earlier, when I was working the cashier‘s-check scam with Lefty, I had the okay from a U.S. Attorney—it was okay to do it as long as I made a record of the purchases so that when the case was over, we could go back and repay the merchant. Later on, another U.S. Attorney took over the case and said that he would have been opposed to what I did from the beginning and might have prosecuted me for carrying out the scam.

That’s why an undercover agent always has in the back of his mind: Even if I keep proper records, make proper reports, follow approved procedures, and nail the badguys, is it possible that I myself might be prosecuted for something? Am I going to be prosecuted for doing my job?

In this case, with Lefty and Boobie and the others, it involved these guns.

When Sonny or Lefty had asked, I told them we had guns stashed down in Florida. I’m supposed to be connected, so naturally I have access to guns. You can’t carry guns back and forth on planes, so the most convenient thing is to have guns waiting for you where you need them.

So when the guys came down to case the bank job, Boobie asked Rossi if he had guns available, and Rossi gave the right answer: Yes, we’ve got guns.

Then Rossi got in touch with the contact agent and asked what we should do if we were asked to give them these guns—would it be okay? The question was passed on to the U.S. Attorney. He said, “Sure, just make the guns inoperable so they can’t fire.” That’s no big deal, it’s easy to do. So then you’re not on the spot, because if anything happens that these guys try to use the guns, they will misfire, and nobody will get shot with our guns.

Then Headquarters was asked. They needed time to ask the legal department. The debate went on for three days. Meanwhile Lefty’s crew decided not to pull the bank job, so they didn’t need the guns. Then our legal department said no.

So we had the U.S. Attorney, who was going to be prosecuting the case, saying yes. We had FBI Headquarters saying no. I work for the FBI, not the U.S. Attorney. Ordinarily I go with whatever the FBI says.

What would I have done in this case? I would have made the guns inoperable and given them to Lefty’s crew. There are some decisions you have to make on your own.

Word came that FBI Director William Webster was impressed by our work and wanted to meet us, the undercover agents working Project Coldwater, in Florida, under whatever circumstances necessary to assure security.

At first I wasn’t too keen on the idea. There would be a security risk to the operation, no matter what. He couldn’t come to us at the club or apartments, so it involved our driving someplace. You never know who is going to see you somewhere, and anyone seeing the three of us together—Rossi, Shannon, and me—would wonder what the hell we were doing there.

But since the FBI officials setting it up were willing to let us call the shots, and since it was the Director, we decided to go ahead with it.

We set it up for midnight in Tampa at the Bay Harbor Hotel, George Steinbrenner’s hotel. It was near the airport, a busy hotel, a place we went to on occasion. It was better there than farther away, because if we were spotted at some really out-of-the-way place, it would be even more suspicious.

The three of us went into the hotel lounge and had a couple of drinks. We didn’t leave for the Director’s room together. We went up one by one, separated from each other by a few minutes.

The Director was there with an aide, and with Tampa Case Agent Kinne, who had coordinated the meeting. Judge Webster—he’s a former federal judge—is a quiet man who spoke so softly that sometimes it was difficult to hear him.

He complimented us for the Florida operation, and me for being under so long in my other operations and penetrating as deep as I had. He congratulated us for the sacrifices we were making to work undercover and carry out this dangerous assignment, and how well we were doing it. He knew the case, who the major players were. He asked for some details, but this wasn’t really storytelling time, so it was brief and general. Basically he was concerned about our welfare and wanted to make sure we were getting the proper support, everything we needed from the Bureau. That’s why he was there, he said; he wanted to see for himself.

We made no complaints. We were honored.

• **

Sonny wanted me to come up to New York and bring $2,500 from our bookmaking “profits.” He said they got hit bad on their football book for three weeks in a row, and he needed the money to put back on the street.

“Remember when you came in the last time you came by John’s house?” he says. “Is that issue still available, the problem that you brought over?”

“I don’t know. I haven’t seen the guy.”

“Well, see him.”

“All right. What about if I can’t get that stuff?”

“You don’t have to get it, just so long as it’s open, it’s still there. I’m interested in that one issue.”

Lefty called shortly afterward.

“Let me get a pencil and get these figures,” he says, “because I gotta go see the guy. What we win yesterday?”

“Yesterday, eleven-sixty.”

“And the other day?”

“The Thursday game? The Dallas game?”

“Yeah.”

“We won twenty-four-eighty.”

“So you’re still up by fifteen hundred for the week.”

“Yeah. Now don’t forget, tell him I’m gonna take a thousand out for that guy’s salary. I wanna give him some money.”

“I don’t know if he’s gonna accept that.”

“Well, I’ll hold off, and then when I see Sonny Wednesday I’ll explain it to him myself.”

Lefty was moaning and groaning. “I don’t feel good. Maybe flu. The doctor gave me a shot, ordered me home for a week. I made reservations for a chest X-ray. I ain’t got no money. Nobody will even take my bets. Listen, Donnie. When you come up here with that for him, you gotta bring me a hundred and five bucks for that rental car, you know? Because that hundred and five I give to my wife. She’s gotta pay the American Express card. I told him about it.”

I delivered the $2,500 to Sonny and told him that the marijuana was still available. He told me that John, the guy whose apartment I stayed at the time I delivered the sample, owed loan sharks more than $200,000. “And since he’s with me,” Sonny says, “I had to vouch for him. He owes sixty grand of that to Carmine. I made him put up a hundred and fifty grand in jewelry to Carmine. I tell you, if I don’t stick behind him, one of the guys is gonna fucking kill him. He runs up all these debts, and then he lies to everybody about them.”

Sonny had bought a hundred pounds of marijuana from a Cuban in Miami and made a deal with some people out on Long Island to sell it. He needed another hundred pounds as soon as possible. He had made a cocaine connection in Miami, and a sample tested out at eighty-one percent pure. He was buying it at $47,000 a kilo. He wanted us to push our heroin connections.

In the office at King’s Court, Pete and Tom Solmo, father and son, were trying to push their drug business to Rossi. Two cocky, bearded guys. Rossi sat behind the desk. Tom, the son, draped in gold necklaces and bracelets sat in an armchair in front of the desk. Pete stood with his arms folded, or paced and kept refilling their glasses with wine and Scotch.

“What we really need,” Rossi says, “is heroin.”

“Horse is tough,” Tom says. “How much marijuana do you need?”

“If you give me a sample, I’ve got people coming from New York on Wednesday and they’ll let me know.”

Pete explained how a marijuana transfer would work. “He comes down, checks into a motel. North Miami, Hollywood, Lauderdale’s fine. He gives me a call. We go to him. He’s got the bread, right? You give me the keys to your vehicle, I give them to my man. He goes, gets it loaded, brings it back. He comes up to the room and gives you the keys. And that’s it. Every bale will be numbered and have the weight right on it. Use us once, you’ll see.”

“My dad finances everything,” Tom says. “I go and work it all out. I know what stuff is good and what stuff is bad. I been down to Colombia many times.”

“He does all the dirty work,” his dad says. “He’s captained boats. He’s been a runner, bringing it in small ways, bringing it in by the ton.”

Rossi says, “The last I brought up to New York, he said, ‘What the fuck you bringing me all these seeds for?’ ”

“We got stuff got no seeds,” Tom says.

“You guys got a strong supply, huh?”

“Fantastic,” Tom says. “We’ll get you five thousand pounds every week. That’s no problem.”

Rossi says, “I gotta be totally up-front here. Up in New York he might say, ‘We’re totally overloaded here, let it go for a week, a month.’ I have no way of knowing. What I’m trying to say, I guess, is I can’t tell you how fast all this will be put together. You understand that I’m only like the fucking go-between.”

“On this other shit,” Tom says, casually taking a small plastic bag of white powder out of his jacket pocket, “it’s good stuff. You don’t know what you’re looking at.” He put the bag back in his pocket. “I don’t think you know that much about the product.”

“No, I don‘t,” Rossi says. “You don’t have to tell me that.”

“You don’t use it, you don’t know it,” Tom says.

“What’s the price on that?” Rossi asks.

“Right there?” Tom pulls out the sample again and lays it on the desk. “This is two-twenty-five.”

“What percentage is that?”

“I’d give it an eighty.”

“We’ve had a ninety-two,” Rossi says.

“How was it tested?”

“How the fuck do I know? All I’m telling you is that the guy gave it to another guy, had it tested, comes back and says, ‘Tony, it’s ninety-two percent.’ I said,

‘Is that good?’ He said, ‘That’s terrific.’ “

“You give me five minutes with your buyer, he’ll buy our shit, because I do have the best stuff in town.”

“You don’t need to have no time with my buyer,” Rossi says. “I just hand it to him. Your problem is when we tell you what we want and you get it, and then we come to you and it might not be the right thing.”

“If he likes that,” Tom says, waving the sample, “that will tell you what he’s gonna get.”

“What about ‘ludes?”

“It depends. If you want five hundred thousand, I got ‘ludes.”

“What they call those, ‘lemons’?”

“It depends. They’re all homemade now. Usually your lemon has Valium in it. You want quantity like that, we’re talking about thirty-five cents apiece. I can give your man anything he wants. Only positive request involved in this is C.O.D. I’m talking about for a start. Once it’s established, I don’t give a shit.”

“What I don’t want,” Rossi says, “is jacking around.”

I come into the office along with Eddie Shannon. Rossi says, “Donnie’s my partner from New York. Eddie’s the action guy around here. You meet Donnie before?”