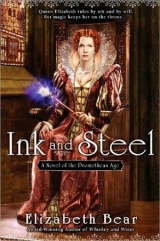

Текст книги "Ink and Steel"

Автор книги: Elizabeth Bear

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 9 (всего у книги 29 страниц)

Mercutio:

Oh, then, I see Queen Mab hath been with you.

WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE, Romeo and Juliet

The second letter arrived in cold, wet April a week or two before Will schristening-day, after the playhouses were reopened from a lent that Will had hoped and failed to spend in Stratford. It was in Kit’s hand, or a clever forgery, and written with some care: no words were scratched out or blotted, and the ink was black as jet on creamy parchment. The tone was much as the first letter. Gold to dross, Will thought, refolding the letter and examining the seal once more though he was growing late for his meeting with lord Hunsdon. The seal was of brittle green wax, imprinted with an image of a goose feather. All carefully chosen to lead Will to an inevitable conclusion.

Gold to dross.

Will Shakespeare had been a country lad, where the reek of frankincense and superstition of Papism still clung. Even if he hadn’t seen in manuscript a few cantos of Spenser’s poem in praise of England’s own Faerie Queene, he would have known the signs as well as any man, although a rational a properly Protestant mind might reject them. Kit’s with the Faeries. Or he’s mad: there’s always that. But he somehow knows mine acts almost as soon as I perform them. And he repeats his plea that I inform him, through Walsingham, of politics and players, and anything else that might befall.

Easily enough done, and no more risky than reporting to Walsingham himself. Which Will still intended. But

I should burn this letter.

But it would be noticeable to carry it downstairs and slip it into the fire, and there was no hearth in Will’s room. After some consideration and a few false starts, he lifted the ticking off the bed and tucked the letter between the ropes and the frame, where it stuck quite nicely. Completely concealed, even with the ticking off: Will crawled under the frame to be sure. Then he got his arms around the rustling ticking and wrestled it back into place, poking the flannel to settle the straw inside the bag. He sneezed at the dust, wiped watering eyes on his sleeve, and twitched the bedclothes smooth.

Mid-April was still sharp enough that Will layered a leather jerkin over his doublet. He hurried through the streets, mindful of slush in the gutters, and crossed London Bridge with the sun still high in the sky. There was no concealment of this meeting: Will reported to the scowling gray Tower itself. He presented himself to the Yeoman Warder at the main gate, struggling to hide the uncertainty of his glances toward the prison while assuring the guards that he was expected. After showing his letter from the lord Chamberlain, he was ushered through, and walked down the long, rule-straight lane within.

The inside of the massive knobbed stone walls was no more comforting than the exterior had been, and he considered uneasily what the murders and covenants of ravens along the edges of the rooftops dined upon. Legend claimed that should the ravens leave the Tower, England’s fall would not be far behind.

Will was not expecting the lord Chamberlain and the lord Treasurer to be waiting for him, apparently at their leisure, a half-played game of chess set on a small cherrywood table between their chairs along with wine and glasses. The footman who opened the door did not accompany Will into the opulent little chamber. A hearth blazed, and a brazier as well the room dryly hot in deference to old men’s bones. Will spared a glance for the figured leather on the walls as the door clicked shut behind him. Burghley and Hunsdon looked up in unison; Burghley turned a chess piece, a white rook, in one crabbed hand.

“My lords.” Will bowed with a player’s flourish.

“Master Shakespeare,” Burghley said, flicking Will upright with irritable fingers. The hand that pinched the ivory castle indicated a third chair.

“Drag that over, won’t you?” Will obeyed, and sat where he was bid to be seated: a little back from the table, well within the cone of warmth from the hearth. He tugged his mittens off, an excuse to look down at his hands. “My lords. From the summons, I had expected we should all be present for this interview.”

“Ah, yes.” Burghley returned the rook to the little army of white pieces haunting his side of the table. The only indication of Burghley’s deafness was by how close he watched Will’s lips, and a slight tinny loudness when he spoke. “We will speak to Master Burbage individually. Master Shakespeare …” The hesitation in his voice was all the warning Will needed.

“My lord, Will said. Not the Earl of Oxford?”

“No.” Hunsdon leaned forward and picked up his goblet. He refilled it from the bottle, then extended the cup as if not noticing the dignity he did Will. Will accepted it and sipped. It could be poisoned, he thought, too late, as heady fumes filled his senses. The wine was red and sharp, not sweet, but with a tannic richness that made him bold. “If your lordship would have pity …”

“Shakespeare,” Hunsdon said. “Your master, Ferdinando Stanley, lord Strange, is dead.” It was as well that Will had finished the wine in the cup, for it tumbled from his nerveless fingers and bounced off a rich hand-knotted carpet, spilling a few red drops on the dark red wool. “Dead.”

“By poison,” Burghley answered. “Or, some say, sorcery. Ten days to die, in terrible agony, Will.” Hunsdon’s voice, his given name.

Will blinked and realized he was standing, his hands knotted on the relief that covered the gilded arms of his chair.

“My lords.”

“Master Shakespeare, sit.” Will sat. “Good.”

“My lords.””

“There is more.” Will leaned forward to hear Burghley’s weary voice more clearly.

“Our Queenis threatened, Master Shakespeare. I have ordered the Irish aliens to present themselves and make explanation of their presence in England. And Essex has accused the Queen’s own physician of treason and conspiring to poison her.”

“Lopez,” Will said. And then quoted sardonically, “The vile Jew.”

“Lies,” Burghley said flatly. “Essex’s machinations. More and more, I believe Essex and Southampton dupes of the enemy. If anything other than the black half of the Prometheus Club, it was a Papist plot. But Lopez has confessed.”

“Confessed? Topcliffe?” It was the name of the Queen’s torturer, the man who had broken Thomas Kyd, and Will spoke it softly.

“William Wade.” Hunsdon breathed out softly through his nose. “Clerk of the Privy Council. Instrumental in bringing low Mary, Queen of Scots, and exposing her treachery. He … showed Lopez the instruments.”

“Ah.” Will gulped, remembering the sear of a red-hot iron by his face.

“My son Robert attended the hearing,” Burgley said. “He and Essex have been dueling in the Queen’s favor for Lopez for months, you understand. We had a hope of saving Lopez until Strange died. Eight times Essex pressed her to sign the writ, and eight times she refused. But now … Essex will prevail, and Lopez will die. Would that Gloriana were a man, and not turned by a pretty man’s face.”

He stopped, as if hearing himself on the brink of treason. “Lopez has been a valued ally, and preserved Sir Francis when we had thought all hope lost. But it may be that now we must sacrifice him.”

“Like Kit,” Will said. If he had intended the words to cut Burghley, they were futile. The old man only nodded. “After a fashion.”

Will coughed against his hand. “How may I serve Her Majesty?” He thought Burghley smiled behind his beard.

“We’ll have Richard revive The Jew of Malta”

“Is Kit not out of favor?”

“Favor or not, we have no other play that may distract the masses and offer a channel to their wrath. Until you write one.”

“My lord?”

“Master Shakespeare. Give me a play about a Jew. Before there are riots in London. Essex’s plot will see innocent persons lynched, and there is naught we can do to prevent it.” Hunsdon covered his mouth with his hand. “I am not a Jew-lover, but it is not they who must be blamed for this outrage.” Burghley tapped the edge of the chessboard in exasperation. Put your damned hand down, Carey, if you want me to understand what you say.

“My lord, Will said. I have never known a Jew.”

“I have one for you,” Burghley answered. “I must warn you. Like Marley’s—” and Will noticed no reluctance in Burghley’s naming of the forbidden poet’s name,—“ your Zionist may not be charming: the groundlings I think would not understand it, were he. But neither must his enemies be. Lord Strange dead. Murdered. And Lopez to hang for it.”

“As my lord wishes,” Will said, and bent to pick his fallen goblet off the floor.

Love is not full of pity, as men say,

But deaf and cruel, where he means to prey.

CHRISTOPHER MARLOWE, Hero and leander

Summer bled to autumn, autumn to winter, winter to the first cold trickle of spring and then through summer until the cycle repeated itself. The seasons in Faerie did not proceed quite as Kit was used to them, but rather each one smoothly into the next without fits and starts, each day a sort of idealized image of what a day in summer, or autumn, or winter should be. He concealed his iron-nailed boots in the bottom of his clothespress in the spacious quarters he was given, and he soon found himself moving through the court, at first as a curiosity and then as a fixture. And while he saw the Mebd often enough at court functions, he was not again summoned before her, or given to understand any purpose in his presence at her court.

Murchaud kept him at arms practice outside, in the slick scattered leaves of the beech wood behind the palace and then in courtyard snow; then in the Great Hall and the armory when that snow drifted over their knees. Kit filled the time between as best he could. He was not accustomed to idleness, and he chafed, and paced, and read and wrote when he had the patience, though all his words seemed hollow and he woke alone most mornings. Some of those mornings, the shape of Murchaud’s or Morgan’s body lay already cold in his bed, an ache filling his belly and a hopelessness behind it. He never lost himself again, as he had after his visit to Sir Francis, but the threat of it hung over him always like black wings. He took to courting Morgan with a practiced distance that seemed to please her very well, while the Elf-knights and ladies treated him as some exotic pet. Like Elizabeth’s wizened little devil monkey on its chain.

One cold February morning, Kit lay against his pillows and watched a dry snow coil and blow beyond the diamond-paned windows. He turned on his side, blew a jet-black hair and days barren of scent from the other pillow. The coverlet of silk and down on his bare skin, the fur-trimmed tapestries on the bed, the transparent diamond panes themselves were luxuries lost on him as he stood and went to the window. He didn’t notice the cold, and only half noticed that the glass did not lay his reflection over the snow.

He was leaner and harder, for all of Faerie’s rich food. Murchaud drove him hard. Kit’s breath frosted the glass. You should have known when you swore off love that you would only tempt fate to bind you in her wicked chains. Still he reached out and idly drew a lance-pierced heart in the misted window, amused by the obvious symbolism, then glanced over his shoulder as if someone might have seen him. When he raised a guilty hand to wipe it clear, he saw the flurry was tapering away, and saw as well a silhouette wrapped in a figured cloak making her way across the drifts below. Ebony locks rustled unbound across her shoulders; something whiter than the snow fluttered in her milk-white hand.

His flinch caught Morgan’s eye; she looked up. Even from this distance he could see her smile and the movement of her hair across tapestry brocade. He imagined what he looked like framed naked in the window, lust stirring as he recollected the scent of her, and stepped to one side, his face burning. She’ll be here in a moment, he thought, and considered for an instant meeting her naked and shameless at the door. She’d laugh. If his blushes wouldn’t set him on fire. Kit,he admonished. For a brazen libertine, an adulterer, a sodomite, an atheist, a fornicator, rakehell, heretic, godless playmaker and debaucher of innocents, you re a sorry state of affairs.

Self-mockery turned his mouth awry as he found a clean shirt, the yoke wrought with whitework, and the green breeches and pale gray woolen stockings that matched a green and silver velvet doublet. Morgan’s favorite colors. He judged it would take her a quarter hour or so to come inside, shed her cloak, and make her way through the palace, but he was still running a hurried comb across his hair when a tap rattled the door. He opened it a moment later, surprised to find not Morgan waiting beyond the door, but a broad-shouldered, black-bearded man: the Mebd’s bard Cairbre, snow still clotting the tops of his boots.

“I happened to chance upon your mistress in the Great Hall,” the bard said abruptly. “As I was on my way to my rooms, she asked me to bid you come to hers.” Kit straightened the lacings on his doublet, pulled his swordbelt from the rack, and stepped into the corridor. “Thank you, Master Harper.”

“Think nothing of it.” The bard’s cheek crinkled beside his eye, his lopsided smile disappearing into his beard. “When are you going to show me your poetry?”

Kit’s fingers slipped on slick black leather and he looked up from adjusting the rapier carriage at his left hip. “A year ago, had I known your interest.”

“I had thought—” A raised eyebrow to go with that angled grin. —“A poet likes a poet’s company, Sir Kit. And it seems to me that you have lovers aplenty, but perhaps could use a friend or two. In any case, your lady awaits.” The bard stepped back, melt water marking his footsteps on the rose and gold flagstones. “Stood I in your boots, I should hurry.”

When Kit looked back, Cairbre was still staring after, a bemused expression shadowing his face. A few minutes later, Kit stopped in the open doorway of Morgan’s room and raised a hand as if to knock on the doorjamb, then paused when he saw her settled on a bench, her skirts hiked above the knee in heavy folds as she struggled with fur-lined boots. Her bedroom window stood open, and a cool, moist breeze blew through it, carrying up a scent at odds with the midsummer colors of her window box of violet-gold heartsease. “My lady.”

“Kit. Your assistance, sir?” She extended a leg, and he knelt before her, taking the soft leather heel cap into the palm of his right hand and sliding the fingers of his left between the furred edge and the silk of her hose. The boot slipped into his hand, dripping melting snow between his fingers, and he turned her leg to kiss above the ankle bone, nubs of knit silk catching softly on dry lips. She cleared her throat, and he smiled and removed her other boot. There was a practiced trick to standing with a sword at one’s belt; he managed it neatly enough. She drew a fistful of skirt into the light to examine the water stains along the hem. She showed him a little more leg than she had to when she swung the skirts into place and stood.

“You summoned me,” he said, following her to the window. The vista was not so different from his, although overlooking the lawn and not the beech wood, and from a higher vantage. But the breeze that flowed through the open panes was a spring breeze, not a winter one, and her window box riotous in bloom.

“I’ve a letter for you,” she said, stroking a pansy with one fingertip as if oblivious to his consternation. “I intercepted it before your friend the Puck could get his hands on it. You and your friend have things yet to learn about keeping your confidences from the notice of the Queen.”

She wouldn’t look up. He caught the damp wool of her sleeve and turned her toward him. “My lady. A letter? Have you read it?” It was more emotion than he’d managed in months.

“Don’t flutter so.” She lifted her fingers to the collar of his shirt and let them trail up his cheek. Her eyes shifted again gray to green, this time, and drifting into hazel as she closed his left eye with a touch of her fingertip sand kissed him softly. “Your secrets are safe with me.”

Despite his effort to stay stern, a smile moved under her kiss. She drew her fingers down his face, and when he opened his eye his breath knotted in his chest, a ragged silken scarf. He let his hand slide down her sleeve, grasped her wrist, raised her fingers to his mouth, lowered them quickly when the gesture brought a memory of tearing cloth. “Don’t tease me.”

“No,” she said, studying his expression as she stepped away, their hands for a moment making a falling bridge between them. “It would be unkind to tease, would it not? Like taunting a tame falcon in a mews.” A little prick with the dagger of her tongue, and a twist to make the blood flow. It stopped him, when he might have heeled her across the room again. He’d had a sharp tongue of his own once, he recalled, but he couldn’t seem to find it after her kisses. “Lady, but give me a purpose, and I will be a falcon on the wing, answering only to your glove. A man is not a toy.”

“No?” But she smiled, and came back with a folded letter in her hand. The seal looked untouched, but he knew well the ways around that. It told him more that the creases were crisp and sharp, a splintered edge still showing where the sheet had cracked. The hand was Will’s untidy abomination, the scrawl of a man who wrote frequently, and hastily and it bore no name or address beyond C. M.

“Thank you,” he said, and tucked it into the pocket in his sleeve, ignoring Morgan’s arch expression. She tapped a knuckle against her lips and turned back to her window garden, pinching dead pansies away. Mint and melissa grew between the blossoms; her fingernails met like snips, filling the room with lemony aromas.

“You wish a purpose, Sir Kit? Poetry and pleasing your lady suffice not?”

“A man gets used to living by his wits. I was never merely a poet, madam.” She pinched another pansy a just-opening bud, this time and brushed it against his cheek. “There are roles for you to play,” she said, tucking the stem into a pink on the breast of the doublet. “But best perhaps if you play them innocent, Queen’s Man. I have your love?”

“Oh, a little,” he lied. “Love is ever increasing or ever decreasing, they say. So better a little love grow great than a great love grow little.”

“Or be lost.” He startled at the softness in her voice as she knotted her hands in her skirts and lifted them to step back. “For what mortal flesh can bear the true heat of an immortal love?”

There’s pain there.With the thought came the urge to go to her. He pressed his palms against his thighs instead. “You expect me to be courted by your enemies.”

“Ah,” she said. “The boy is clever. And that green looks well on thee: we’ll make an Elf-knight of thee yet.”

“When mine ears come to a point, or horns sprout on my forehead. Then, perhaps.”

“Horns, sweet Kit? Or antlers?” But she smiled and blew a kiss. “A task. Very well. When thou dost write thy William in return, see thou if canst encourage him to weave a few tales of his country youth into his plays.”

“Arthur and Guenevere?” Kit asked, letting a little of the irony filling his mouth soak the words.

“By the white hart, never!” Morgan laughed and shook her hair over her shoulder. “We’ll have enough of that from Spenser, I warrant. Although chance and legend alter us: I was as fair as Anne and Arthur, once upon a time.” She raised a fistful of hair black as sorcery and shook it in the light.

“Gloriana does like to play on the Faeries, and it strengthens us to be spoken of so I think it should please Master Shakespeare’s Queen and thine as well.”

“Madam. A little task. But something. Your wish is …”

“Oh,” she interrupted, giving him an airy wave at odds with her earthy grin. “And a play for Beltane, I think. Something we can see performed for Her Majesty the Mebd.”

Beltane. He tasted it. Short notice, but he’d had shorter. Ten weeks.“Have you a subject?”

“Intrigue.” She straightened the blossom on his breast. “And passion. Mayhap one of those great lost loves of which we spoke. Drystan and Yseult. Something ill-starred would suit us both, and Her Majesty. But mind that thou lookst wistful and sigh and fret while thou’rt composing, and see who chooses to speak with thee. And on what matters.”

“My lady. Drystan and Yseult. No, Orpheus, I think.” But he was smiling as she took his elbow and led him to her door, her stockinged feet whisking against the flagstones like a cat’s white paws. A stalking horse. I’ve played that role before.

‘Dearest & most-esteemed leander:

Your letter does indeed find me very well, if exceeding busy. I fear I have not had occasion to converse with my wife since our last encounter but I shall pass your felicitations when I may. The subject is complex, but suffice to say I have hopes for rapprochement. I am attending your request for books & broadsides: they will follow under separate cover. You will be amused to read that, following hard on the discovery of a poisoning plot against the Queen of which you will no doubt have heard, plays about Jews are once again popular in London, & we are becoming reacquainted with some names that languished in danger of loss. I hope these humble words find you well. In any case, thinking of you I am moved to remember Sir Francis & a certain incident with a lemon bush. I wonder if my predecessor had such a sour experience of his own.

April 29th, year of our lord 1594.

Your true and honest friend Wm… .’

Incident with a lemon bush. Kit set the letter down on a marble-topped table below the window, and smiled. Clever William. How I miss thee, and wrangling late into the night on scansion and wordplay and line. Lighting a taper at the hearth, Kit remembered Cairbre’s invitation. Poets are so often thought solitary. But we need the society of our fellows as much as any tradesman.

The taper lit a clever lamp, which burned a blue spirit flame, and this Kit bore to the table beside Will’s letter. It would cost him the seal, but that little mattered. What mattered were the pale words, written painstakingly in invisible lemon juice, that slowly caramelized into visibility as he toasted the letter a few inches above the flame, holding his breath lest it flicker and the edge of the paper catch light. When the words burned dark enough to read, Kit laid the letter in the light from the window and leaned forward to blow out the flame. He tucked a few strands of hair behind his ear and closed his eye for a moment, then reluctant, frowning bent forward. And read. And blasphemed. And read it once again.