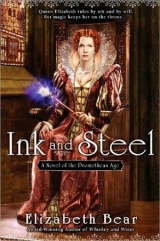

Текст книги "Ink and Steel"

Автор книги: Elizabeth Bear

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 10 (всего у книги 29 страниц)

Beatrice:

Speak, cousin; or, if you cannot, stop his mouth

with a kiss, and let not him speak neither.

WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE, Much Ado About Nothing

‘My beloved Adonis I read with disquiet your words & the implication that unsavory individuals have taken an interest in your activities. In pursuance, I would consider it a great kindness if you should contact Mary Poley in Winding lane. She is the abandoned wife of one Robert Poley, with whom you are acquainted, but more to the point she was the sister of the late Dr. Thomas Watson, the poet, who was long a friend to me & her husband is greatly unfelicitous to her, & to her son. You need have no fear that she will expose you to him, and she may be a great source of intelligence as to his actions.’

Will tilted the letter into the light of the candle which he had used to scorch the concealed words from between lines more innocuous and manifest. The heated lemon juice was only pale brown against the cream-colored paper, but Kit’s precise hand was easy to discern.

‘Poley will not see to their maintenance & so, in Tricky Tom’s memory & out of mine own friendship with the lady, I have been of what assistance I could to her in the past, & so I believe she should be grateful for a kind word or two, even from a stranger who mentioned my name as the name of a friend. She may be of assistance in warding yourself from that same Robert, her husband; Mistress Poley is a good woman, & much concerned with the future prospects of her son, a likely lad.

Will’s nose wrinkled in amusement. Her son. Kit. Are you insinuating the lad is your bastard? And then he frowned, and nibbled the edge of an ink-stained thumbnail, uncertain why the thought made him so uneasy.

My mistress has asked that I bid thee, my beloved friend & only begetter of whatever joy is afforded me, remember the pastoral fancies of thy callow years & find ways to set them into verse. I am minded of county ballads & old tales, I imagine you too are conversant with, of Nimue, & the Irish & Welsh stories & those of Yorkshire & Scotland: Finvarra & Oonagh & their kin.’

You want me to tell fairy tales to the Queen, sweet Kit? He sounds lonely. You should sound lonely, exiled from home and friendships, and worried about the ones you’ve left behind.

Will closed his eyes. When he opened them, he read more quickly, and without pause.

‘Have a care for Poley, Will. If he & his have realized that you are my replacement, you may find yourself with dangerous enemies: have a care not to be associated too plainly with Hunsdon, Burghley, Oxford & their friends. I will dare declare Robert Poley & Thomas Walsingham scions of the enemy, & ask you be wary of them. It is of import that you acquaint yourself with the politics, if you have not already done so: Essex’s group do support the Queen, although they are more interested in their own advancement than the stability of the crown. Raleigh is a little better: I can like the man for his ideals, at least, which are intellectual & inquisitive, but he is a popinjay. (Those are not sentiments to be repeated, sweet Will, lest you withal blacken my name further than mine enemies have already.) More dangerous are Poley & Baines (& I now think Thomas Walsingham), who have made themselves so seeming indispensable that their word be taken even over mine, & I have proven my worth to Gloriana in great extremis. I read with great delight the pages of yr. Merchant you included with the books, & have returned some suggestions along with mine own current project. Also, I am quite engaged with your character of Beatrice; she reflects your Annie, does she not? but feel Hero could be stronger or mayhap more delicate of constitution; her speeches now show nowt but woman scorned, & women (even scorned) are no force to be trifled with. You may wish if you can so contrive to seek Her Majesty’s approval. Gloriana fancies herself something of a poet, & was of infinite service making that infamous she-wolf Isabella more a breathing woman than the Dragon of legendry. Further…’

It went on for a page and a half, line-by-line comments on the play, ending wryly,

‘have enclosed some notes for the play or more like masque my mistress has commissioned of me, something of an orgy & something of a revel, & I am feared only half-suited to my poor talents. I wish you would examine them with some haste, & return post to me through the usual channels. I think on thee & London daily. With all love & affection, your dear friend leander.’

Will read the letter over again, permitting himself a few more smiles. Very well then, if Her Majesty will sully her hand with playmaking, I will offer her mine own poor words to dirty herself on. He stopped, and frowned, and looked up at the darkened window. And then he fetched quills the stained one for the iron gall, and the white one for the invisible ink and sat down at the table and composed himself to write.

Beloved companion of mine art

Will stopped, brushing the nub of vane that lingered on his quill against his upper lip. He glanced at the stack of pages beside his elbow, the ink on Kit’s manuscript so black it gleamed, and frowned.

‘ Have a care not to be associated too plainly with Hunsdon, Burghley, Oxford &’ Kit, how do I write to tell thee that lord Hunsdon has claimed Burbage, Kemp and I withal into a playing company, now that Strange is dead? That we are become the lord Chamberlain’s Men?

He ran a hand through his hair, streaking it for once with lemon juice instead of ink. And then he pulled a fresh sheet of paper toward himself, and wrote ‘Dearest Annie’ instead.

Three days later, Will and Burbage trudged through a cloying summer rain to the Spread Eagle, a tavern near the bear baiting pits that could be forgiven a certain lack of charm for the virtue of its pies, although for safety’s sake Will wouldn’t drink anything weaker than ale. A filthy floor and walls dark with smoke and grease did nothing to brighten its face, but Will had forgotten to eat through the afternoon, and his stomach grumbled painfully when the wench—another attraction of the Eagle—slid his supper under his nose. Burbage looked up at the sound and laughed, pushing bread through bloody juices, then stuffing the soaked sops into his mouth.

“You’ll waste away to a ghost,” he said. Will broke the pie open and scooped aromatic meat and onions to his mouth. Gravy trickled into his beard; he wiped it on the back of his hand.

“Oxford’s help isn’t help,” he said in a low voice. “If I suspected he were competent, I’d believe he meant to impede rather than assist. At least Jew and Merchant are showing a success, for all I’m hard-put to believe we staged them so swiftly as we did.”

“Has there been word of Lopez?”

Burbage, chewing thoughtfully, only turned his head from side to side. “He’ll hang, for all Burghley can do. We may be lucky enough that our work will fend off riots and worse, however. And the hunt is on for Papists. I marked adozen recusants in stocks today. Tis a time to keep your hand in your sleeve, methinks.”

“Mayhap.” Will busied himself with pie and ale, unwilling to meet Burbage seye.

Rain still rattled the shutters, and all London smelled of damp. All summer, the rain had barely lifted long enough for a man to wring the water from his cloak before descending again.

“I’ve a play in mind that might catch Her Majesty’s fancy. A tale of two warring houses. Another tragedy.”

“We could use a comedy for the Theatre. Now that the plague has lifted, that we’ve lifted the plague, aye, well, yes. People want happy things. Can you write me a comedy by All Saint’s Day, Will?”

“I wot.”

A shadow fell across the table as a stocky figure, cloak dripping rain, passed between Will and Burbage and the light.

“William Shakespeare.” A sonorous voice spoke in educated tones. “You re going bald on top, Will.”

“The heat of a well-used brain,” Will replied. “I see you have experienced the like.”

“Not I, Burbage interjected. I keep mine too well greased with ale to rub and burn. Sit down, George. Since you’ve invited.”

The poet George Chapman unwound his cloak from under his beard. Will shuffled the bench away from the trestle, and Chapman sat heavily.

“I’ve a letter from Spenser.” Chapman slapped the table to draw the wench’s attention. “He’s back in County Cork, would you believe it? Master of the Queen’s Justice, in Ireland. Sad days when the greatest poet in a generation must politic for his bread.”

Will choked on piecrust and reached for his ale, spilling half of it acros shis lap when Chapman thumped him between the shoulders. Burbage glared, lips compressed, though Will thought he had recovered nicely. He pulled a kerchief from his sleeve and dabbed at his breeches.

“He’s completed his Faerie Queene?”

“A canto or two.”

The girl came over; Chapman refused ale or wine and ordered instead small beer and stew. Will wondered if his famous temperance was distaste for drunkenness, some Puritan bent, or merely the caution of a man with no head for liquor.

“Will you grace us with another play this summer, Will?”

“One or two.” Will wrung his sopping kerchief onto the boards and spread it across the trestle to dry. “A tragedy first, and Dick Burbage wants a comedy to warm a heart or two. I may write him half a dozen this year, if he stays unwary. I’ve been reading the Italians, and my lord Southampton wishes me to come spend some weeks in residence with him before the summer’s out, and write him poetry”

“May God ha mercy on this house,” Chapman said. “A plague upon you, then,” Will answered with rare good humor, considering his breeches were sticking to his hose. “And yourself, George? What have you been working at?”

“Master Marley’s Hero and leander,” Chapman replied. “I still mean to finish it. Don’t flinch like a girl, Master Burbage. For all his excesses and a tawdry end, our Kit deserves to be remembered for his gifts as well. And with his Jew in production again, I can see no better time to press the issue. Kit would have wanted to be recollected.”

Will shrugged. “Isn’t that what poets crave?”

Chapman’s stew arrived. He busied himself for a moment buttering bread with absolute attention, and then looked up first at Burbage, and then turning his broad contemplative face to study Will.

“No, William.” He set the bread down on the boards beside his dinner. “I think you’ve something more to prove than skill, to select an example. I think you are a man who is afraid to be alone. After your death, if the ages forget your name, so be it … so long as we know you today, and tomorrow, and touch on your wit.”

Will swallowed ale to wet his throat. “That may be, George. At least I’ve a wit to touch on, yes?”

“At least,” Chapman answered, and turned his concentration on his board, bench creaking. “I’ll show you what I’ve got of Hero if you’d like it.”

“Exceedingly.”

“Done, then,” Burbage said, suddenly rising. “Will, if you would walk with me? You had wished to speak to my father about buying shares in the Chamberlain’s Men.”

Will stood, leaving the crumbs of his dinner on the trestle. “Richard, I have intentions to visit a woman tonight. Perhaps tomorrow?”

Burbage nodded, and Will continued, “George, I shall see you at church.”

“Indeed you will. Or Friday at the Hogshead. Or are we meeting at the Mermaid, on Bread Street?”

“On Bread Street. That’s where all the rogues and scoundrels have gone.”

“In your company I’ll find them.”

Will paused, hearing the smile in the older poet’s voice. He scooped the ale-soaked rag from the end of the table and without turning threw it over his shoulder. He didn’t wait to find out if it wrapped itself around Chapman’s head as satisfactorily as the wet thwack of cloth hitting flesh suggested; instead he broke for the door, trusting Chapman’s dignity to be too great for a really rollicking pursuit.

Will’s first impression of Mary Poley was of a bright, sudden eye, half occluded by a tangled spiral of brown-black hair, gleaming through the crack in a door she gripped so tightly her knuckles went white along the edge.

“Who is it?” Her sodden skirts shifted: she leaned a knee with her weight behind it on the door, in case he tried to push through.

“William Shakespeare,” he said. “The playmaker. Are you Mistress Poley?”

“I am.” She didn’t relax her grip on the door, and that jet-shiny eye ran up him from boot to beard and back down without meeting his gaze. “Are ye looking for a washing woman?” Her tones were educated, not surprising, given her family.

Will lowered his voice. He’d expected more genteel poverty, somehow. “I’m looking for Master Kit Marley’s friend.”

That hand flew to her mouth and she stepped back involuntarily. Will didn’t waste a gesture; he pressed the flat of his hand against the timbers and shoved the door open, careful not to strike Mistress Poley in the face. He slipped through sideways and pushed it shut behind, standing back against the wall as she cringed away.

“Mistress Poley,”

“Shh!” A jerk of a gesture over her shoulder. “My boy’s asleep. Finally. He has terrors. Poor lad.”

Will lowered his voice. “Mistress.”

“What’d ye know of Kit Marley? And why’d ye trouble my house?” House, she said, drawing all fourteen hands of herself up like a stretched-taut string, as if the rotten, spotless little chamber with its two sad pallets on the floor and its peeling plaster were a manse.

“Kit Marley was …” Will stopped, and frowned at the little woman trembling with rage, a banty hen defending the nest. She’d be perfect for Burbage, he thought. No wonder Kit liked her. And then she shoved a hand through her unkempt hair, tilted her head back to glare at him, and sniffed. Will sat down on the floor, his back against the door. “—my friend. And he cared for you, so I know he would have wished mine assistance to you, if you will so kindly accept it.” He reached into his pocket and tossed a little felt bag clinking on the bare boards between her feet. She glanced down, but didn’t step back or stoop to pick up the coin. Will drew a long breath through his nose, closed his eyes, and finished, still mindfully soft.

“And your husband had a hand in killing him, and I’m interested in learning why.” She glanced over her shoulder: the small form curled on one of the pallets still lay unmoving, and she turned her wary, wild-animal expression back on Will. She probed the bag with her toe barefoot, Will saw and seemed to consider for a second before she stooped down like some wise little monkey and made the coins vanish beneath her apron into the stained folds of her skirt.

“On a darker day,” she said, crouching and resting her back against the wall, but not sitting, “I might give ye that Kit was killed for my sins.” She balled fists reddened with scrubbing against her eyes, whipcord muscle flexing across skinny forearms.

“But it wasn’t Robert wielding the dagger.”

Will suddenly felt very tired, as if the space of a few feet across the floor between himself and Mistress Poley were a rushing river that must be swum. “Do you see your husband often, Mistress?”

She pulled her hands down. “Never an I can cross the street in time. But there might be yet a thing or two I may aid you with, Master Shakespeare.” She nodded, a sage oscillation of her head, and then she grinned. Will blinked in the dazzle of her smile as she squared her shoulders and rose against the wall without setting a hand on the floor, realizing that she was no older than he. Not that you re quite the beardless boy any more.

“Aye, Will Shakespeare, then. A friend of Kit Marley’s is a friend of mine.”

Barabas:

Some Jews are wicked, as all Christians are.

CHRISTOPHER MARLOWE, The Jew of Malta

Kit’s eye never shifted from the unrippled surface of the Darkling Glass, his fingertips hooked under the lip of the carved flower petals marking the frame. So long as his hand rested among the cold, sculptured blossoms, he heard the words of the players clearly: Burbage’s metered, resonant voice declaiming, ‘He jests at scars that never felt a wound’, Burbage and Kemp, and Will, and the rest of the company moved about the shaded stage before an empty house, on an early autumn afternoon. Sunlight glared on the packed earth of the yard, outlining a not-quite-perfect circle with the bite of the stage taken from it, its margins defined by the gallery roofs. Kit leaned closer, tracing the action behind the mirror, where small forms moved sharp and crisp in the cold, polished blackness of the glass. But it was cold. Cold as a scene viewed through a rippled casement.

Kit drew his brown woolen cloak tighter, tugging the hood up to hide his hair and the black band of the eyepatch crossing his face. He settled his sword at his belt with his left hand, hiding it under a fall of cloth, glanced over his shoulder, and finding himself unobserved thought very carefully about a dark corner of the Theatre’s second gallery, in the private boxes above and behind the stage. It came into view, a familiar concealed corner behind a pillar and a bench where lovers might steal a kiss. Or where a cloaked man might linger and in his own person overhear the voice of Richard Burbage speaking beautiful words:

‘By a name,

I know not how to tell thee who I am:

My name, dear Saint, is hateful to myself,

Because it is an enemy to thee.

Had I it written, I would tear the word’

A warm breeze brought Kit the scent of the streets and the distant barking of a dog, and the contrast to Faerie’s cool air and birdsong came home with a pang. He sweated in his cloak, and saw that the players sweated as much in their costumes, and thought, how much I miss thisonly a few moments before he realized that he could not, in fact, step back to Faerie as simply as he’d stepped away. I’ll need to find a looking glass.

He wasn’t worried: he thought he might have two or three days before the pain set in, and if he couldn’t visit Will because Will would be watched there were other errands Kit could busy himself upon. Once night fell. In the meanwhile, he crouched against the wall in a garishly painted box at James Burbage’s Theatre, first to be so named, and concealed his face, and watched men who had been friends rehearse a play.

Several of his own poor scribblings had made their mark upon these boards those sanded scorches were from an overturned firepot during a miscarriage of Faustus, some years since and by this current rehearsal, Kit judged that Will Shakespeare had made a fair mark of his own.

The play progressed. The shadows slid, and Kit slid with them, his eyes tinging and a smile on his lips. He sighed and settled down on the floor cross-legged, peering around a bench, his left arm going numb from elbow to wrist while he leaned his chin on his arm. He didn’t dare blow his nose, and so sniffled quietly and uncomfortably into the rough wool of his cloak. And then the truth of what he was seeing sank in, and he sat back against the wall, rapier sticking out to the side like a stiff, unwieldy tale.

Two warring houses and their children lost coming to their senses too late, uniting when the future they might have defended is lost to them. Not Catholics and Protestants, but Capulets and Montagues. Kit bit down on his finger to keep from laughing out loud.

I’d almost forgotten. His family is Catholic.

Injustice and undue accusations, your simpering Hero and her slander, your stern Beatrice and your clever Benedick united over all their own protestations. You’ll work our trickery even on the Queen, won’t you? And Burghley and the rest can go to Hell with their persecutions and their factions. And Kit’s grin turned downward and he tapped a thumb on his lip, only half aware of the excited babble of the players on the stage below.

Kit sat up straighter and then scrunched into the darkness as a tall, beskirted figure, her gray-streaked hair almost the same mousy shade as Kit’s bound up on her head and her dress sagging at the bindings as if it had been worn for hard travel.

She scanned the galleries imperiously; he caught a breath in his teeth and held it, didn’t let it slip until her eye was past. One last voice, Will’s rose above the abruptly stilling clamor from the stage. He must have his back to the yard.

But Kit didn’t drop his eyes from Annie Shakespeare’s face to see Will turn. Didn’t look away from the Amazon’s form as she set her heel and laid each palm softly on the curve of a hip. Tilting her head, the smile in her eyes never touching her lips. Will must be looking by now, by the utter silence in the stage and yard. By the way Annie angled her chin up, to command a glance across the packed earth and cinders and up the five-foot lift of the stage. She drew a breath. Kit saw her shoulders settle as her bosom rose and opened her mouth and never got a word into the air, as a whooping Will Shakespeare piled off the stage and swept her off her feet and spun her up in the air.

And that’s as good a distraction as I’m like to get, Kit thought, and slipped away down the stair into the drawing twilight, whistling to himself when his elf-booted foot met the dusty cobbles of the road.

Some hours later, footsore and sweltering, he stepped back into the doorway of a shuttered cookshop across the alley from a tavern he’d stay away from if he had any sense at all: the Groaning Sergeant, Mistress Mathews sole domain. He leaned into the shadows, trusting the cloak to hide the outline of his body against the brown wood of the door, lifting the pommel of his sword to tip the scabbard straight so it wouldn’t tap the wall. He sighed. Francis could help me. If I had the wit to go to his house from Faerie, and speak to him straightaway. I’ll never find my way in now. But then I wouldn’t have seen the play.

Men came and went. Kit stretched against the wall as the hours drifted by, keeping himself awake through force of will and force of habit. Traffic was steady; the Sergeant’s clientele stayed awake late. When the lights within flickered out longer after curfew than the law, speaking strictly, allowed and the custom left, he did permit himself to slide down against the door frame and doze. But no more than doze; even if no enemy found him, it would profit him little to be taken and jailed as a vagrant, a masterless man. Toward morning, he crept from his vantage and forced the cellar on a house which had been boarded up for the summer, abandoned to the threat of plague as the residents guested with some relative or country friend. He stole a meager supper from a few forgotten pots of preserves, and slept. Curfew found him again lurking in the shadows with a clear view of the Sergeant.

Kit’s patience was rewarded sometime in the blessedly cool hours before matins, as he shifted the cloak and his sweat-lank hair off his neck. The smells of morning baking filled the air, and his stomach grumbled. Tis been too long since you went hungry, Marley. You re soft.

But then a figure emerged from the alleyway beside the Sergeant and with an unconcerned glance at the apparent derelict in the doorway opposite slipped inside. A tall man, hair platinum in the pre-dawn, hands broad even for his frame.

Richard Baines.

Kit unwound his fingers from the hilt of his rapier. He checked the sky, cocking an ear for church bells, and decided discretion might serve better than boldness. At least clouds were gathering: a not-unexpected stroke of luck, given the chill wetness of the summer, but it would make his cloak less unlikely and Baines easier to shadow.

Kit emerged from the doorway, tipping his rapier straight again so the outline wouldn’t show, and staggered around the corner to the alley. It didn’t take as much effort to move drunkenly as he would have preferred: two nights propped in a doorway left his neck and back complaining, the muscles of his thighs stiff as if they’d been nights in the saddle.

Thunder crackled; Kit skulked behind empty barrels under a second-story overhang. He kicked a dead starling aside and settled himself to wait, but a few moments later the sky pissed rain like a drunken Jove. He tugged the hood of his cloak higher, wet wool slicing his limited vision in half. Inside the cookshop, pots clattered, onions browned. Christ wept.

Never trust to luck.In a quarter hour, Baines cloakless, ears hunched into his collar left the Sergeant. Poley walked alongside, better equipped for the rain in a gray oiled cloak and high boots. Kit swung in behind them, fifty feet or more.

Baines’ shoulders, clad in a brown leather jerkin that grew slowly darker with the rain, bobbed through a crowd, and Kit for once was glad of the other man’s height. The men wended north. The grit between his soles and the cobbles turned to mud, but Kit’s feet stayed snug in Faerie boots and he never slipped. Poley and Baines led him down alleys and through mires more wallow than highway. A bloated rat corpse swept down the gutter. Pedestrians ducked into taverns and doorways, but Baines and Poley continued. And Kit followed. Baines never looked back. Poley did, but Kit was careful to vary his distance and his walk, and one shrouded, sodden figure looked much like another.

He got lucky: they took the Bridge rather than a wherry south across the Thames. The two men stepped down another side street and into an intersection. Kit recognized their destination: a well-favored establishment known as the Elephant, a Southwark tavern whose sign peeled artistically rather than from simple neglect.

Kit checked his step as they continued around the building to where, he knew, a ramshackle stairway led to a warm and comfortably appointed room. He stepped under an overhang and leaned into the corner by the garden wall, gasping like a hooked fish. His stomach clenched on emptiness, but he forced himself to straighten and walk silently through the rain.

His hand itched on his sword hilt. Not his left hand, to keep the blade tuckedunder his cloak, but his right, ready to draw the blade whickering into the air and cast that cloak aside, to run Baines and Poley down, shouting. To run them through before they could climb those stairs.

Where’s Nick Skeres?he thought, picking his way over litter and startling a feral pig nosing through garbage. It fled in a clatter of trotters, and Kit held his breath lest the sound should bring investigators. But the rain probably covered it. Where’s Frazier?The name brought a twist of coldness into his belly, and kept him from thinking about who might be already waiting in that room.

He released the rapier’s hilt and thrust the lank strands of hair out of his eye. They stuck to his cheeks and forehead; he stifled a sneeze and swore. Morgan will put me in a hot bath again.It was her cure for everything, insane as it sounded, but it hadn’t killed him yet.

Baines and Poley had just reached the landing as Kit glided around the corner and slipped beneath the whitewashed frame of the stair. They did not shut the door. Kit looked up at the timbers and sighed, knowing from experience that the landing and much of the stair were visible through that entryway.

Perhaps I can’t make the climb in a cloak. The sword would be enough trouble, but he wasn’t leaving that behind. He circled through puddles, using a few wan flickers of lightning to get an idea of the strength of the crossbracing holding the stairs, wishing he had a bit of leather to bind his hair. It drifted again into his eye and mouth as he lifted his face. He drank in the unclean savor of London rain, blinked a particle of soot away. A pang of hunger left him dizzy for a moment; he sighed and took hold of the thickest timber. Quickly, Kit, or you’ll miss what you’ve come to hear. You don’t know who’s in that room. ALL you have is a very nasty suspicion indeed.

And one that could mean a great deal of danger to Will, especially if his friend’s secret plan to undermine the ill-feeling between Protestants and Papists came to light.

Kit dropped his cloak in the driest corner and ran each hand up opposite sides of the rough-hewn timber, glad the edges had not been planed to corners and the bark was only haphazardly smoothed away. He grabbed as high as he could, locked fist around wrist, and half hopped, half pulled himself into the air. He wrapped his legs around the pillar, the rough surface burning skin through clothes so much for these hose and breathed. One. He reached as high as he could, coiled his arms around the pillar, and dragged himself a few inches, cursing rain and splinters.

Something stabbed his thigh, working deeper as he shimmied up. He kept his grip and pressed the scarred side of his face against the timber. Another flicker, and a halfhearted growl of thunder. Kit struck his head on a crossbrace and flinched, but held on. The stars he saw were brighter than the lightning. A slow hot trickle winding through his hair was soon lost in all the swift, cold trickles; he hoped the thump would be as lost in the sound of the storm.

The voices he strained to hear almost vanished under the pattering of droplets; Kit chased them, hoisting himself onto that crossbrace and straddling it. His arms and legs trembled. The crossbrace dug into his back, and the splinter burned in his thigh. Good work, Marley. And how get you down?He wiped his hair out of his face again and saw dilute blood on his fingers, though the bump on his head seemed superficial. He closed his eye and listened through the rain: first to the commonplaces of intelligencers in the tones of Baines and of Poley, reports of Catholics and Puritans Kit dismissed as no longer relevant to his service.

Until … “no, I haven’t seen Nick today, but he intended to attend. He must have been delayed at some trouble, my lord. I can tell you until he gets here that your Shakespeare’s been well behaved,” Poley said in his sharp, sardonic tones. “He spent the night in his room with his wife. Had supper sent up, and the candle went out shortly after. Not a peep: he seems apt to take the Queen’s penny and write his plays as he’s told.”