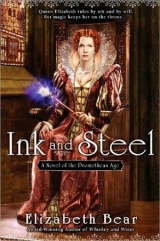

Текст книги "Ink and Steel"

Автор книги: Elizabeth Bear

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 3 (всего у книги 29 страниц)

Touchstone:

When a man’s verses cannot be understood, nor a

man’s good wit seconded with the forward child

Understanding, it strikes a man more dead than a

great reckoning in a little room. Truly, I would

the gods had made thee poetical.

Audrey:

I do not know what “poetical” is. Is it honest in

deed and word? Is it a true thing?

Touchstone:

No, truly, for the truest poetry is the most

feigning; and lovers are given to poetry, and what

they swear in poetry may be said as lovers they do feign.

WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE, As You like It

May became June, and Burbage’s prophecy held: the plague carried off another thousand souls, rat– and cat-catchers roamed the streets with their piles of corpses and their narrow-eyed terriers, and the playhouses stayed closed. Will’s new lodgings were over the tavern Richard Burbage favored, north of the River and closer to James Burbage’s Theatre. They were considerably more luxurious, possessing a window with north light for working by and a bed all to Will’s own use. But Titus grew a scant few manuscript pages, and Will swore to Burbage that they might as well have been written in his own dark blood.

Will sat picking at a supper of mutton and ale in the coolest corner of the common room, his trencher shoved to one side and Titus spread on the table, the ink drying in his pen. The food held no savor, but he set pen in ink bottle anyway and worried at the meat with his knife so he wouldn’t sit there only staring at the mottled page. How long did one go without writing before one stopped calling oneself a playmaker? It wouldn’t be so bad if the pressure to have the stories out would relent. Instead of nagging after him like a lusty husband at a wife just delivered of the last babe. The image made him smile, and then it made him frown. How long since you’ve seen Annie last? If you can’t write plays, you could go home and watch your son grow.

He picked the pen up, and a fat drop of iron gall splattered a page folded in four for convenience of writing. But his grimace of irritation was interrupted when Burbage walked out of the warm summer twilight, crossing to Will’s table after a quick examination of the room. A taller man might have had to duck the thick beams. Edward Alleyn would have been stooped just crossing but Burbage strutted through clots and eddies of drinkers like a rooster through the henyard. A flurry of conversation followed as the custom recognized London’s second-most-famous player. Will gestured Burbage to the bench.

“Good even, Will. I’ll not sit: had your fill of mutton?”

Since what you have to say will no doubt rob mine appetite.”

Burbage shrugged, so Will smiled to take some of the sting from his words.

“Whither?”

“We’ll to Oxford.”

Burbage offered Will a handclasp.

This time, Shakespeare took it to stand. “A long walk, he said,” though Burbage’s grin alerted him.

“Just across London Bridge,” the player continued, softening his voice. “We re stayed for at the Elephant, Cousin. Step quick!”

Will gulped the last of his ale and hung the tankard at his belt, then gave the landlord’s son a ha’penny to run his papers and pen up to his room. The leftover mutton and trencher would be given as alms to the poor or more likely go into the stewpot. He wiped moisture from his palms onto the front of his breeches and took Burbage’s arm.

“I feel as if I’m summoned by a patron, and I shall have to confess so little done on Titus—”

Titus this and Titus that—” Burbage led him north. “Vex me not with Titus. What thorn is in your paw on that damned play?”

The houses and shops lining London Bridge came into view. Will checked his stride as the foot traffic clotted, keeping one hand on his purse. Stones clattered under hooves and boots. Will squared his shoulders, hooked thumbs in his belt, and charged forward so abruptly that Burbage struggled to pace him, bobbing like a bubble in an eddy in his wake.

“Will!”

Will shook his head as Burbage caught his elbow.

“Will, what is it?”

Will jerked his chin upward, and Burbage’s eyes followed the motion.

The Great Stone Gate loomed over them, cutting a dark silhouette across a sky, pink and gray with twilight. The last light of a rare clear sunset stained the Gate and all its grisly trophies crimson, and dyed too the elegant wings of wheeling kites and the black pinions of the Tower ravens.

“If Kit hadn’t been murdered in an ale house,” he said low, steps slowing, “his head could be up there among the traitors.”

“What heard you about the Privy Council proceedings?”

“I heard that Kyd and that other fellow Richard Baines named him as the author of heretical documents. That he stood accused of atheism, sodomy, and worse.”

“Kyd under torture, Burbage amended,” tugging Will’s arm. “Baines—someday I’ll tell you about Baines.”

Will had almost to be dragged several shuffling steps before he was walking on his own.

“I’ve writ not a good word since.”

It was Burbage’s turn to stumble. “Will.”

Will rested a hand on Richard’s shoulder. “What?”

“You know what Kit was charged with. Sayst thou you know something of the truth of those allegations?”

Will knew his eyes must be big as the paving stones underfoot, his face red as the sunset painting the Gate.

“Regarding Kit’s alleged sins, I’ll not doubt it. But no, I’m not likely to be charged the same. We shared the room for prudence’s sake.”

“Then what?”

A shrug and a sigh. “We were friends. His hand was on my Henry VI, thou knowest, and mine in his Edward III. If he can come to such an end, whose Muse dripped inspiration upon his brow as the jewels of a crown drip light what does that bode for poorer talents?”

Poorer talents?”

They were swept up in the tide of pedestrians before they had gone three steps, in the stench of the Thames, in the rattle ofcoach-wheels and the blurred notes of poorly fingered music: the sprawl and brawl of London.

“Not so, Will. You’ve an ear on you for cleverness and character better than Kit s. And you re funnier.”

“I can’t match his technique. Or his passion.”

“No. But technique can be learned, and you won’t, perchance, end your life drunken and leaking out your brains on some table in a supperhouse. If Kit had the patience and sense of a Will…”. He raised his hand to forestall Will’s retort.

Will’s shoulders fell as the air seeped from his lungs.

“I listen, Master Burbage.”

They came out of the shadow of the Gate and its burden.

“The Privy Council would have cleared him, Master Shakespeare. As it’s done every time before: with a wave of the hand, words behind closed doors, and a writ signed by five or seven of the Queen’s best men, Kit Marley goes free where another man would go to Tyburn. How many men charged with heresy and sedition are free to rent a mare and ride to Deptford, and not on a rack in the Tower? And you’ll be afforded the same protection.”

“And the same enemies.”

But it wasn’t just the danger of his own position, or the unwritten things twisting in his brain. He plainly missed Kit.

“You’ll make enemies any way you slice it, with your talent. Ah, here we are.” Burbage pointed to the scarred sign hanging over a green-painted door, and then led Will down a dim, stinking alley toward the back, where a wobbling wooden stair brought them to the second story. Will clutched the whitewashed railing convulsively, despite the prodding splinters. Although, if the whole precarious construction tumbled down, a death grip on the banister couldn’t save him. A door at the top of the stair stood open to catch what breeze there was. Burbage paused at the landing and softly hailed Oxford within, while Will stood two steps below.

“Enter, Master Players.” Edward de Vere did not stand to meet them, but he did gesture them to sit. Stools and benches ranged about the blemished table, and the small room was dark and confining despite the open door: it did not seem the sort of chamber an Earl would frequent. Incense-strong tobacco hung on the air in ribbons, the sharp, musty tang pleasing after the stench of thestreets.

“Lord Oxford, as you’ve summoned us,” Burbage said, taking a stool. Will doffed his hat, reseated it, and sank onto a bench and stretched his legs.

Oxford nodded to the player, but turned his bright eyes to Will.

“How comes the play, gentle William?” The question he’d been dreading, and Will twisted his hands inside the cuffs of his doublet, folding his arms. He almost laughed as he recognized Kit’s habitual pose, defensive and smiling, but kept his demeanor serious for the Earl. An Earl who studied him also seriously, frowning, until Will opened his hands and shrugged.

“Not well, my lord. The story’s all in my head, but Times being as they are…”.

“Yes. I understand thou hast tried thy hand at some poetry. A manuscript called Venus and Adonis has been commended to me. Compared to our Marley’s,” Oxford’s nostrils flared momentarily, as if he fought some emotion unfinished work. “I’d see it read.”

Heat rose in Will’s cheeks as he glanced down at his shoes.

“You’d see my poor scribblings gone to press, my lord?”

“I would. And command some sonnets. Canst write sonnets?”

Oh, that stiffened his spine and brought his hands down to tighten on his knees. Burbage shifted beside him, and Will took the warning.

“I’ve been known to turn a rhyme,” Will answered, when he thought he had his tongue under control.

“I need a son-in-law wooed,” Oxford said. He stood and poured wine into three unmatched cups. Will raised an eyebrow when the Earl set the cups before Burbage and himself. More than mere politeness, that.

“Henry Wriothesley, Earl of Southampton: I’d see him married to my daughter Elizabeth, where I can perhaps keep him from trouble. He’s close to Essex and to Raleigh, no mean trick. Kit’d befriended Sir Walter’s lot, their School of Night, so-called and learned a few tricks by me of the philosopher Dee. It’s trouble waiting to happen: too many of the Queen’s favorites in one place and rivalries will brew.”

Will’s eyebrow went even higher at the familiar form of Marley’s name.

“And you wish me to Dedicate thy book of poems to Southampton.”

“As if thou didst seek his patronage. Afflict him with sonnets bidding him marry. Raleigh is an enigma: there’s no witting which way he might turn in the end. Essex is trouble, though.”

“Though the Queen love him?” Burbage said, when Will could not find his tongue. Robert Devereaux, the second Earl of Essex, was thought by many a dashing young man, one of Elizabeth’s rival favorites and a rising star of the court. But her affections were divided, the third part each given to the explorers Sir Walter Raleigh and Sir Francis Drake. And there was something disingenuous in the look Oxford drew across them both, just then; Will was player enough to recognize bad playing.

“Sonnets. Sonnets, and I couldn’t write a good word to spare myself the chopping block.”

“Gloriana,” Oxford said, toying with his wine, “is a shrewd and coy Queen, equal to the title King of England which she has once or twice claimed. Despite her sex. Ah, would that she had been a man.”

That tripped Will’s tongue. “Do you suppose she mouths those same words, when she feels herself alone?”

Oxford tilted his head as if he had not considered it. “Master Shakespeare, I would not disbelieve should I hear her Maid of Honor mutter such gossip to the bees.” He stared past his guests to the smoky vista beyond the open door.

“So. Thou wilt write me these poems? Or write Southampton these poems? And bring me the manuscript for Venus and Adonis, that the ages might know it?”

“Will you see Hero and leander published as well?” Will hesitated at the cloud that passed Oxford’s face. He liked Kit as well. And then Will smiled. Kit had had that about him, the ability to inspire black rage or blind joy.

“It’s fine work, isn’t it?” Oxford didn’t wait for Will’s nod. He knocked the dottle from his pipe and began to pack the bowl again. “Chapman, another of Raleigh’s group proposes to complete it and see it registered. In Kit’s name, not his own. Decent.”

Burbage rocked back in his stool, rattling the legs on the floor. “My lord, you’ll put Will in a place where, if Southampton is flattered, they may become friends. Even if the courtship fails, we’ll have an eye in Southampton’s camp.”

“There’ve been a dozen attempts on Queen Elizabeth’s life in as many years: your Kit’s sharp wit helped foil two of them, and he was friendly with Essex’s rival, Sir Walter. Now we have neither a hand close to Essex, nor one close to Sir Walter. Intolerable, should what I fear come to fruition. Essex has links to the…” He stopped himself.

Will observed calculation in that pause. “What you fear, my lord, or what fears Walsingham?”

Surprise and then a smile. “The two are not so misaligned. We were one group, the Prometheus Club, not too long since. All of us in service of the Queen. But Essex and his partisans are more interested in their own advancement than in Britannia. So, Will. Wilt woo for me, and win for my daughter?”

Will swallowed, shifting on the hard bench. “I was to write you plays, my lord. And you would show me how to put a force in them to keep Elizabeth’s subjects content and make all well. I was not to spy for you.”

Oxford tapped a beringed finger on the table. “I’m not asking thee to spy, sirrah. Merely to write. Not plays No. The playhouses are closed, Will, and they’ll be closed through the New Year. We’ll try our hand there again, fear not: but in the current hour, the enemy has the upper hand.”

“The enemy. This plot against the Queen. Closing the playhouses is a sort of a skirmish? An unseen one?”

Oxford smiled then softly. “You begin to understand. They know what we can do with a playhouse. Art is their enemy. Puritans. Naught but a symptom. Walsingham and Burghley are ours, after all.” Oxford drained his cup. “I offer you a poet’s respect. Nothing is so transient as a play and a playmaker’s fame. Except a player’s.”

Will looked at Burbage, who sat with his hands folded between his knees, thumbs rubbing circles over his striped silk hose. Burbage tilted his head, eyes glistening. Twas true.

“The poem’s the thing, then,” Will said, when he thought he’d considered enough. “Give unto me what you would impart, and I will wreak it into beauty with my pen.”

Oxford twisted his palm together, fingers arched as if to ease a writer’s cramp. “Excellent.” Another intentional hesitation. “Your play. Titus Andronicus. Send it me. I fancied myself something of a poet in my youth. Perhaps I can be of some small aid.”

My lord,” Will answered, covering discomfort. “I shall.”

Was this the face that launch’d a thousand ships,

And burnt the topless towers of Ilium?

Sweet Helen, make me immortal with a kiss.

Her lips suck forth my soul; see, where it flies!

CHRISTOPHER MARLOWE, Faustus

Kit’s heartbeat rattled his ribs inside his skin. He clutched the balustrade in his left hand, Morgan steadying him on his blind side as she led him down the sweeping marble stair and into the midst of creatures diabolic and divine. His riding boots clattered on the risers: inappropriate to an audience with the Queen of Faeries, he thought inanely. But it was homely and reassuring that they hadn’t had time to make him boots and that the doublet, for all its fineness, bound across his shoulders.

“Breathe,” the ancient Queen whispered in his ear. “You’ll need your wits about you, Sir Kit, for I can offer thee but small protection, and my sister the Queen is devious.”

He turned his head to glimpse her; the movement brought a twisting sharpness to the savaged muscles of his neck and shoulder, which were stiffening again. Morgan must have seen him wince, for her fingers tightened. “Thou’rt hurting.”

“Fair face of a witch you are,” he answered with a stab at good humor. “Without herbs or simples better than brandy to dull a man’s pain.”

She paused on the landing above the place where the stair began to sweep down and made a show of fussing right-handed with her skirts. He leaned on the rail and on her other arm while the pale gold-veined stairs reeled. “I’d dull your pain,” she answered, glancing at him before ducking her head to flick the soft moir one last time. “And thick your tongue, and set you rhead to reeling. Which canst ill afford when you go before the Mebd, Sir Poet.”

Her hair moved against the back of her neck, a few strands escaping the braid. He stopped his hand before it could brush them aside. A blade of guilt dissected him at the impulse, and he embraced the pain, gnawed at it. He had nothing left to be unfaithful to, save Elizabeth, now that his sweet Tom had discarded him. Kit welcomed the cold, the distance that came with the thought. Nothing like ice for an ache. She’s very like Elizabeth would be, had she leave to be a woman and not a King. “Queen Mab?”

“The Mebd,” Morgan corrected, steadying his arm again. Below, faces turned up like flowers opening to the sun. “Queen of the Daoine Sidhe.” She pronounced the name maeve, the kingdom theeneh shee. “She has a wit about her Ah! Sir Kit. Come and meet my son.”

“Mordred?” Kit asked, putting the smile he couldn’t quite force onto his lips into his voice.

“Dead at Camlann,” Morgan answered. “He was fair. Fair as thou art, ashen of hair and red of beard. A handsome alliance. Come and meet Murchaud the Black, my younger.”

Something in her tone made him expect a lad of thirteen, fifteen years. But the man who met them at the foot of the stairs, a pair of delicate goblets in his hand, was taller than Kit by handspans, his curled black hair oiled into a tail adorned with a crimson ribbon, his beard clipped tighter and neater than the London style against the porcelain skin of his face. Kit’s palms tickled with sweat as he met the man’s almost colorless eyes, saw how the broad span of his neck sloped, thick with muscle, into wide shoulders. It was a different thing from the inexplicable warmth he felt for Morgan. More raw, and less unsettling. He’d like to see those black curls ruffled.

“Mother,” the lovely man said, extending a crimson glass of wine. His voice was smooth, at odds with the power in his frame.

She unwound her hand from Kit’s elbow, but let her fingers trail down his arm before she stepped away. Her son pressed the second goblet into his hand, taking a moment to curl Kit’s fingers about the delicate stem. The touch lingered, and Kit almost forgot his pain.

“Your reputation precedes you, Master Poet.”

“Sir Poet, Morgan corrected. I knighted him while no one was looking.”

“You did? Mother, bravely done!”

She laid a possessive hand on his shoulder. Kit looked after her in confusion, and she gave him only a smile.

“Things are different in Faerie, she told him,” and dusted his cheek, below the bandage, with a kiss. “Now drink your wine and go ye through those doors and court and win a Queen.”

“You’re not coming with me?”

“Kit. Show them strength, not a cripple leaning on a woman’s arm.”

He met her loden eyes, then nodded, tossed back the wine, and set aside the glass. Rolling his shoulders under the too-tight doublet, he stepped into the rivulet of courtiers threading toward what must be the Presence Chamber. Frank stares prickled Kit’s skin as he followed the crowd, conscious of the antlers and fox-heads, the huge luminescent eyes and the moss-dripping armor of those who moved around him.

Masques, he told himself, and didn’t permit himself at first to return the curious glances. Hooves clattered on the floor on his blind side: he flinched and turned to look, and a naked satyr caught his eye and bowed from the waist. Kit blushed and stepped back, looking at the floor.

As if I had an idea of precedence here.The rose-and-green tiled floor rolled under his boots like the rising, falling deck of a ship. He hesitated and put a hand on the paneled wall. A woman brushed his arm, elegantly human except that the diaphanous robes which stroked her swaying hips and breasts seemed to grow from her shoulders like drooping iris petals.

Then his attention was drawn by an antlered stag, richly robed in velvet green as glass, resting one cloven hoof on the jeweled hilt of a rapier and walking upright like a man. Kit’s pulse drummed in his temples and throat.

Adrift, he thought, and raised his right hand and touched the silk handkerchief binding his bandage. The fingertips of his other hand curled into detail carved upon the wainscoting. I don’t know what to do. A novelty. I wot a knife in the eye does change one or two things.

“Follow me.” A sharp voice dripping wryness. Kit looked down, putting it to a wizened man who seemed all elbows and legs like a grasshopper. He came to Kit’s belt; his long ears waggled under a fool’s cap. “Before Her Majesty waxes vexed.”

“Waxes vexed, and wanes kind?” Kit pushed against the wall. “Dizziness, Master Fool. You know me?”

“Your plays have a wide circulation.” The little man grimaced: it crinkled his face so oddly that Kit at first did not recognize a smile. “Art Marley, and I’m Goodfellow, but mayst call me Robin if I may call thee Kit. We’re fools both, after all, and of an estate.”

“I’ll not dispute it.” Kit pressed the heel of his hand to his injured eye, as if the pressure could ease the throbbing that filled his brain. “I’ve the belly to make a go of it if you’ll steady me, Master Fool. One fool hand in hand with another. A Puck for a puck.”

“You’ve the belly for many things, I hear.”

“I’m notorious.” The banter was tonic to a flagging confidence.

A tall man with four horns and the notched ears of a bull swept past, wearing a breastplate of beaten gold and trailing a cloak of burned blue velvet and vair. A circlet crossed the man’s fair brow, just under the horns, and Kit returned his stare.

“I am notorious.”

The bull-horned man turned his head, maintaining the eye contact, and almost stumbled over a side table. Kit wished he had a rapier to rest his hand on; a heady rush he liked better than wounded dizziness filling his breast. As if air filled his lungs again after a blow to the gut.

I’m Kit Marley. I’m Kit Marley.He curled his lips into a grin and stiffened his shoulders, put a cocky sparkle in his eye. Flickering torchlight picked out the river of

Fae, limned them like the demons of Faustus, and the heat of it stroked Kit’s cheek. The bull-horned man turned suddenly to watch his feet.

Marley the poet. Christofer Marley the playmaker. Marley the duelist. Marley the player, the lover, the intelligencer. I’ve the honeyed tongue to seduce wives from husbands and husbands from wives, secrets from seditionists and plots from traitors. I’m Christofer Marley, by Christ! I can do this thing.He tasted a breath, and then another one. For Good Queen Bess. For Elizabeth. I can do this thing and any other.

“Lead on, Merry Robin,” he said without letting the grin slide down his face, though it tugged his stitches and filled his mouth with musky blood. “And show me your merry men.”

“Tis not the men that need concern you. Tis the maid stands at their head.” Twiglike fingers encircled Kit’s wrist and the elf tugged him forward, creeping on many-jointed toes.

Kit had a brief, swirling impression of heavy paneled doors worked in bas-relief with masterful artistry, designs more Celtic than Roman. The throne room was longer than it was broad, the floor tiled in patterned marble of rose and green, the dark windows hung with rippling silk and open to the night. The Fae moved freely, clumping in knots of whispered conversation, calling witticisms across the table set with glasses and wine.

Kit’s head throbbed with the scent of rosemary and mint, strewn with flower petals underfoot. Robin Goodfellow tugged his fingers, and Kit turned his head slowly so he would not miss a detail on his blind side. No hush fell when he entered, but the conversation flagged for half an instant before Robin led him forward. On the far end of the hall, raised on a dais, the Queen lifted her head. Kit would have gasped if he’d had any wonder left in him.

She curled in a beaten gold chair, languid as a lioness. A cloth of estate stretched over her head, and as Kit approached uncouth nails ringing on the paving stones she raised eyes that struck him through the heart. It wouldn’t have taken much to send him to his knees, true, but Robin was there, and made the stumble look a genuflection. Kit didn’t look up, but the image of the Queen’s golden hair knotted in braided ropes stayed with him, and the haunting perfection of eyes that caught the light and glimmered one moment green, one moment violet, like orient jade.

That most perfect creature under heaven,he thought, the moon full in the arms of restless night.

She moved an arm, by the sound of it. Stretched in leonine grace. Unfeeling of the hard, cold stone he knelt on, he imagined the purple silk of her mantle drifting from a wrist as white and smooth as a willow branch. He imagined the perfect pale mask of her face marked with a rosebud smile, and shivered deep in his soul. Her voice was furred like catkins, soft as the wind brushing his hair, and he heard a rustle of slick cloth and a jingle of bells, as if she stood, or stretched, or danced a step and stopped. His breath froze in his belly when she said his name. She’s just a wench,he thought desperately. She’s ensorcelled me. This is sorcery. Glamourie.

“Gentle Christofer.” Another whisper of bells. Robin got up and shuffled aside. He didn’t dare raise his eyes. “You grace our court with your presence. We have seen your work. It pleases us, and we know of your other duties before your Queen, and Gloriana pleases us as well.”

Somewhere, he found a voice, although it didn’t sound like his own. “You are gracious, Your Majesty.”

“Look upon us, she said,” and his chin lifted without his conscious will. I am bewitched,he thought, and then realized how close she had somehow drifted, silent as a thistledown. She reached out with soft fingertips, laced them through his hair, and traced the outline of his ear as if exploring a flower petal. He whimpered low in his throat, an anxious whine, and gritted his teeth as a low, amused chuckle swept the room.

They knew what she was doing to him. His breath came like a runner’s around the fire in his chest, but he managed to answer in pleasant tones. “Yes, Your Highness.”

Like velvet stroked along his spine, like a hand in the hollow of his back, her voice kept on.

“I’d grant you a place in my court, Master Poet. Your old life is lost to you. Will you play for my pleasure, sir?” A little ripple of delight colored her tone at her own double meaning.

“I’m sworn to another,” he began. The hardest words he could imagine speaking then, but the Mebd cut him short with a wave of her lily-white hand. Pearls and diamonds slid about her wrist when she moved, and emeralds and amethysts sparkled on her fingers.

“Hath been our royal pleasure to assist our sovereign sister Elizabeth in maintenance of her realm, whether she wits it or not. She’ll not grudge us your service, Master Poet”

“Sir Poet.” A voice like the yowl of a cat after the Mebd’s silken perfection. A voice from his blind side. Kit turned his head. Morgan stood beside him and a few steps back, her hands loose by her sides as she dropped a brief curtsey to the Queen. “I’ve knighted him, sister dear.”

“Ah.” The Queen let her fingers trail across Kit’s neck. “Stand, then, Sir Poet.” Her voice said she smiled, but her eyes didn’t show it, and Kit struggled but didn’t have to take Morgan’s subtly offered hand.

“A man cannot serve two Queens, Your Highness,” Kit said softly, against the pressure within that told him to throw himself down and kiss this woman’s slipper, the perfect hem of her perfect gown. Much as it may pain him. He shook his head, in pain.

“Oh, thou art fairer than the evening air

Clad in the beauty of a thousandstars;

Brighter art thou than flaming Jupiter

When he appear’d to hapless Semele:

More lovely than the monarch of the sky

In wanton Arethusa’s azured arms …”

“Your Faustus,” she said, but she seemed well pleased. She stepped back, a silver slipper gliding through the rose petals curling on the tile, and Kit felt something snap in the air between them as cleanly as if he’d broken a glass rod between his hands.

“We know it.” She settled back on her chair. “Thou canst never go home, Christofer Marley. Art dead unto them.”

Kit swallowed around the dryness in his throat. The dream was broken, the moment of perfection fled like the touch of the Queen’s soft hand. His belly ached, his chest, his ballocks, his face; he trembled, and only half with exhaustion.

“Your Highness,” he said, and his voice was again his own, if raw as the cawing of crows. “I crave a boon.”

“A boon?” She leaned forward in a tinkle of bells. “We shall consider it. What offer you in return?”

His luck had been running. Let it run a mile longer. He stepped away from Morgan, nearer the throne, dropping his voice.

“A bit of information, Your Highness. You have an interest in Elizabeth’s court?”

She smiled. Oh yes, he’d guessed right, from the fragments of information gleaned from her speech and Morgan’s.

“Sir Francis Walsingham, Queen Elizabeth’s spymaster? He lives, in hiding.”

“As do you,” she answered, with a slight, ironic smile. “It signifies. What wish you in return?”

“Let me speak to him but once. I have information I can give no other, and it is vital to the protection of the realm. If Elizabeth’s reign means something to your Royal Highness and I can see your sister Queen is dear to you, I beg you. On bended knee. Let me make my report.”

“And?”

“And secure my release from service.” For all his practiced manner, he could hear the forlorn edge in his own voice, and imagine the mockery in Elizabeth’s. ‘Am I so easy to set aside then, Master Marley?’

The Mebd watched him as he suited action to words, bowing his head, sinking on the stone steps of the dais though they cut his knee like dull knives. The queen sighed; Morgan shifted from foot to foot behind him. At last, he heard the sibilance of her mantle as she nodded, and her voice, stripped now of glamourie.