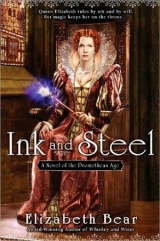

Текст книги "Ink and Steel"

Автор книги: Elizabeth Bear

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 6 (всего у книги 29 страниц)

“And our half? Our half, is it still?”

“Elizabeth and England, we stand for. Tis rough work. Even for a rogue like myself, whose works drip with gore, unacquainted with gentle thoughts.”

“Can the man who wrote Hero and leander claim to be unacquainted with gentle thoughts?

“Acquainted and yet unacquainted.” Kit shifted before the iron could scorch his leg. The tip was not yet glowing. “Tis a quaint small thing, a poem about passion Kit, it’s a poem about leander’s arse.” The iron slipped: Kit caught it right-handed and hissed, juggling a twist of sleeve around the metal to shield his hand.

How smooth his breast was, and how white his belly,

And whose immortal fingers did imprint,

That heavenly path, with many a curious dint,

That runs along his back, but my rude pen

Can hardly blazon forth the loves of men.

Will’s long nose dented sideways with the twisting mouth. “I faith, I think betimes you purpose to shock. You underestimate the wit in your pen, rude as it may be, or so I’ve heard tell. From those with more interest in the loves of men than I.”

“Rude enough for most purposes.” It was his last chance to impress upon the man the severity of his choices. Is this pen enough to write with? He lifted the poker until the smoking end hovered a finger’s width from Shakespeare’s eye. “Will. Move not.”

“Kit, what are you about?”

There was a little squeal in Will’s voice, good. And a tremor under it as Will pressed his head back hard against the wall. Ah, there was a red glow at the tip after all, like a pen dipped in blood. Excellent.

“Look on it well,” he said, watching Will’s shoulders rise as if that could protect his face from the cherry-hot iron. Kit swallowed bitterness when it rose up his throat one more time, but couldn’t quite get the taste down. A thunder in his chest like beating wings prevented it. Will’s eye was gray-blue and looked very soft; he didn’t blink, and the dark pupil swelled as if it would encompass the whole of the iris in velvet black. Will’s eyelashes curled from the iron’s heat; Kit drew it back a little. “That could be thy final vision. Imagine it. Can you imagine? Image yourself unhanded like Stubbs, or racked like Kyd, or branded and blinded like me. Damn you, William Shakespeare. See it.”

The apple in Will’s throat bobbled. He dared not nod.

“Tell me once more you mean to do this, and I’ll let it lie.”

Will’s mouth worked. “I mean to do this thing.”

“Bloody hell.” But Kit said it tiredly, and turned and strode to the table, and drew back his arm. The poker was heavier than a rapier, but he managed well enough to be pleased: the strength wasn’t out of his shoulder. A thump first, and close on its heel a sizzle. Kit thrust the fireplace poker through the body of the unfortunate hen off-center, his aim untrue with his missing eye and into the mortar of the wall. It didn’t hold: he stepped back from the clatter as it fell. “Damn you to hell, William Shakespeare.”

“Oh.” Will stood. “I can probably manage that for myself.” He came and threw an arm over Kit’s shoulder, and Kit dropped an arm around his waist. “I knew you wouldn’t put my eye out.”

Kit heard an edge of hysteria in his own laugh, and wished he could afford to get drunker. Clearheadedness was the last thing he wanted. “I wouldn’t rely on that knowing too much, my friend.”

Hark, countrymen! either renew the fight,

Or tear the lions out of England’s coat …

WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE, First Part of King Henry the Sixth

Will itched with the sensation of words filling his brain, like a pressure behind his eyes. Kit saw it: Will could tell from the sly way the other poet abandoned him in the drawing room amid cider and staling crumpets, beside a leather-surfaced secretary fitted with every tool for writing a man could want. Will fetched another cup of cider and settled himself with his back to a window so light could fall over his shoulder. He proceeded to deface first one and then another sheet with his cramped looping hand. Fewer mark-outs this time, fewer words scratched through. It was well that Kit walked into the edge of the door frame on his way back into the room, or Will might have upset the ink pot in startlement. Will glanced up. The light had changed and he’d turned in his chair to follow it without noticing, and he’d covered half a score of folded leaves with notes and lines of dialogue, scanned lines sketched here and there with a double-underlined blank, waiting for the perfect word.

Christus lacrimavit, Kit growled, rubbing his shoulder. He’d changed to a shirt of cobweb lawn, this one without scorches on the sleeve; a doublet of black silk taffeta, slashed crimson, was slung unbuttoned around his shoulders.

“Walsingham is resting. How comes it?”

“It comes.” Will pushed the pages across the desk, waving Kit an invitation. “I don’t remember you so clumsy, even drunk.”

“If I were still drunken, I’d have something to answer for. Tis noon. Didst not hear the bell?” Kit riffled pages until he found the first. “I’ve been tripping on nothings since …” He tapped a knuckle on the eyepatch without looking up.

“Not yet accustomed?”

“It seems only an hour gone by when I had two good eyes to see with. Will, that any mortal man can write such verse so quickly is an affront to angels. This exchange betwixt Marcus and Titus with Titus unhanded, and his sons beheaded, and his daughter dismembered …. Why dost thou laugh? it fits not with this hour.”

“Why, I have not another tear to shed.”

That’s good, I warrant. It does sing true: to read it, you can see the man smile, and it is terrible.” Crisp pages rustled; Kit held each up, opened along the folds to read slowly, tasting the words. Learning them,Will thought. Is he truly so blind to the irony?

He found himself looking at his friend’s face for a shadow of pain, and saw only a player’s concentration, a thin line etched between Kit’s dark brows. Will went to the window. He rested a hand on the glass and stood looking over the garden, watching yellowing leaves twist in a soft October breeze.

“If you mean to go about London unnoticed, you might dress less like Christofer Marley and more like a cobbler’s son. I can bring a false beard from the Theatre, and a bit of gum. No one will see aught but that and the eyepatch, an you play the role.”

“A cobbler’s son.” Amusement in that. “Only a man who dresses like a glover’s son would say so.”

One more rustle, then silence as the pages stopped turning.

“We’ve come from close places, haven’t we, Will? And worn very different roads to the same end: poetry and service.”

“Your father saw the value of an education.”

“As yours did not. I may have to teach you latin.”

Shakespeare snorted. Another leaf tugged loose of a pear twig before Kit spoke again. “I shan’t be in London long.”

“Where will you go?”

“I cannot tell.”

“Where can I write to you?”

“I do not know.”

Will paused. “You’ll be on some mission for Her Majesty,” he said, considering. “I understand.”

“No,” Kit answered. “I go tonight, under cover of darkness, to beg my service back from Gloriana, in point of fact. I have been offered refuge by a foreign monarch, that I might live.”

“That you might live?” Will set his rump on the window ledge. Kit still stared at the pages, but his eye no longer scanned the lines.

“What mean you?”

“I am …” A breath, and a sigh. Kit’s shoulders rose and fell as he stepped back from the desk, scrubbing his nails on his doublet. The motion arrested;he plucked at the material, pulling it into the light to examine. “It is a little Kit Marley, isn’t it? No matter. I’m poisoned, Will, with a slow poison, and the cure lies in a foreign land. If I do not return I shall die.” He ruffled paper. “Horribly, I am assured.” Which was truth, Will decided, watching Kit. Or as much of a truth as anyone was like to get from Marley.

“I shall worry.”

“And I for thee. You’ll be in more danger. But I shall discover how a letter may find me, if a letter may find me, and send you word on the means.”

“I may take a month in Stratford come Christmas time. If the plague stays in London. If the playhouses stay closed. If you send a letter.” Will resumed his chair and reached for a fresh sheet. He could feel Kit’s smile resting on him.

“Annie is speaking to you again.”

“Annie thinks I should see my children, as she had Susanna write me, before we’re grown and gone. I’ll be sleeping in the third-best bed with Hamnet, I imagine. And she’s yet a better wife than I deserve, Kit: there’s few enough women who would even pretend to understand why a man might leave kith and kin to crawl through the gutters of strange cities, all for the grace of a poem.”

“There’s few enough men who understand it,” Kit replied. “And, here or in Stratford, I may be capable to make a visit, now and again.”

“From overseas?”

“Not so much overseas as under them,” Kit said cryptically. He glanced at the window, measuring the light, and fanned the folded sheets upon the desk.

“Shall we work on these a little, before I must disguise myself for Her Majesty?”

“Will Sir Francis loan you a cloak?”

“A hood should suffice in a carriage.”

“Keep the doublet: you’ll want to look pretty for the Queen. Otherwise she won’t believe you re Marley.”

“At least I don’t dress like a Puritan,” Kit answered, with a scornful glance for Will’s brown broadcloth, and reached across the desk for a pen.

Dido :

What stranger art thou that doest eye me thus?

Aeneas:

Sometime I was a Troian, mighty Queene:

But Troy is not, what shall I say I am?

CHRISTOPHER MARLOWE, Dido, Queen of Carthage

‘You’ll want to look pretty for the Queen.’ Kit caught himself examining his fingernails in the light of the candles burning on a gilt wooden table, and let his hands fall to his sides. There was ink along the knuckle of his forefinger, but that was nothing unusual, and at least he was tidier than Shakespeare. Will took no pride in his appearance or his scribing whatsoever.

And writing lines such as his, he does not need false pride. Anyway, tis Sir Walter’s duty to look pretty for his Queen, and not mine. Queens will jus thave to take me as they find me.

Gallant thoughts, for a man alone in a small white marble room with no escape, when anything could be coming down the narrow passageway he’d entered through. A long table and a few narrow windows dominated the room, lit between flickering shadows by a rack of candles like stag’s antlers. He wondered if he were quartered in a priest’s closet, or some stranger appurtenance and how riddled the walls of Winchester might be. Walsingham had led Kit through a secret passage within a chapel at Winchester Palace, and then taken Kit’s dagger and abandoned him. Kit wasn’t sure what garden the small, tight window looked over, but it admitted a breath of air, and over the flowers he could smell the river. At least it wasn’t an abattoir, as in Deptford. The Queen was letting him cool his heels. He examined the ink stain on his fingertip again: it resembled a map of Italy. He pressed back a mousy handful of hair. At last, soft footsteps sounded beyond the panel, and Kit turned with a question on his lips, hoping it would be Walsingham come to retrieve him but fearing it could be another sort of visitor altogether one armed with sharp steel and a quarrel. The panel slid open, and Kit stepped forward. And met, open-mouthed, the masterful gaze of his Elizabeth. Alone and without escort.

“Highness!” he stuttered, and bent a knee somewhat credibly, for all his head-kicked foolishness. His breath hurt his throat, but he held it and kept his eyes on her shoes. Gold cloth, sewn with pearls. Toe-pointed slippers clicked daintily on the marble as she stepped forward, her hem so stiff with lace that it made a sound brushing the threshold like a curry down a horse’s back. The scent of herbs and musk as she hesitated, and Kit wondered for a moment if she might strike him. She was not unknown to lay her wrath on those who displeased her.

“Sir Christofer Marley,” she said, after a while. He choked on that, held breath and looked up at her despite himself. Into a prescient smile under the crimson tower of her wig and eyes wide with mockery and amusement. Yes, we know something of your adventures. Stand up straight, lad: even Queens tire of bended necks when they haven’t an axe to hand. He stood. “Your Highness is well-informed.”

“We pay a great deal for the privilege,” she answered. “In gold and coin, and in the flesh and blood of our loyal subjects. Has she claimed thee?”

“Your Highness?”

“The Queen of Faerie,” she said, with a lift of her chin. She shut the panel behind herself and claimed the center of the narrow chamber. Kit’s pulse fluttered in his throat: a different sort of awe than what the Faerie Queen produced. This was the awe of temporal power, of strength and age and a wit equal to any man’s.

“She is the pillar the sky is hung from. The beautiful pitiless lady. Has she claimed you?”

“She wishes to, madam,” he answered. “But her sister, called Queen Morgan, was the one who knighted me.”

“And bedded you? Oh, don’t blush like that. For all tis engaging. We know something of the ways of the Fae. So. Stolen by Faeries, Queen’s Man. And yet you seek an audience with your Sovereign, and we are disposed to grant it. Speak.”

“Your Highness.” Her eyebrow arched under its paint as he sought for words.

“Do women always fluster you so badly, Kit?”

“Only when they’re Queens.” He genuflected again, straightening hastily when she coughed.

“Sir Poet,” she said, not unkindly. “We are pleased that our subtleties have preserved you, and well-pleased are we to see you well. But now our good Walsingham tells us you beg release of your oaths of service. Your Queen would know why, and what adventures befell you. Our intimate Spirit, Burghley, had you buried, and those were of a certainment not our orders.”

“My Queen.” He would have gone to one knee again, but her worn, irritated fingers caught his elbow and held him on his feet. He couldn’t look Gloriana in the eye, though she put her fingers under his chin and tilted his face like a maiden aunt with a wayward boy. “What choice is left me?”

He saw her lips purse under the masque of her paint, smelled the marjoram and ambergris and civet that clothed her. She tilted her head to examine his eyepatch and the scar that ran beneath it. “What befell thee, Queen’s Man?”

“Your Highness knows.”

“Your own words, man, and be quick about it.”

“A dagger in the eye, Your Highness.” He choked. “Thomas Walsingham’s men.”

“Your death was to be an illusion, Christofer Marley,” she said, seeming not to notice when her words rode over his. “A false body put in your place, and you spirited overseas. As was arranged in the letter you should have had under our seal. You have given much, and demanded little. We thought to make recompense.”

“It was not so, Your Highness.”

“We see.” Her hand left a trace of scent on his skin as she stepped away, her gaze steady on his scar. “I’ve witnessed worse, but it is not pretty. And earned in our service. You are a poet, she continued without a breath. Give us a poem.”

That was a challenge. She smiled when he drew himself up.

“And yet before I yield my fainting breath,

I quite the killer, though I blame the kind,”

Kit whispered, amazed at his own audacity.

“You kill unkind, I die, and yet am true,

For at your sight, my wound doth bleed anew”

“Falsely said, but pretty. Like all sentiments of poesy. As a poet myself, I’ll forgive it. Our subterfuge Burghley’s, Thomas Walsingham’s, and mine was to have saved you.”

Kit nodded. A cramp knotted his stomach; he had to brace his knees or they would have failed.

“Dead men are hard-pressed to die again. My Queen. I knew you could not prove false to me, for all you are a Prince, you are a woman as true as any woman, and the mother of a son.”

She stepped back as if stung, and then shook her head in admiration and rue.

“Hist! Kit Marley, you’ve got a tongue in you. Wilt convert me to atheism now?” She leaned close, voice confidential. “You are privileged in your loss this once and once alone. Unmarried Queens do not have children, sir.”

“Your Highness.”

“As I am bid …” She smiled then, gentled. “We are given to understand that we owe you life and reign twice over, Sir Poet. We meant to reward you with your life, but it seems you have that in spite of us. What would complete thee?”

“Do you know, Your Highness, of Thomas Walsingham’s faithlessness?”

“Not unlike his cousin,” she said, “whose trickery painted me to a stand where I must have my royal cousin executed. The men who support me are true to my reign, but they will work at cross-purposes. We believe he is upright in his conviction that your death was warranted for all he was misled to that conclusion. Do not ask yourself revenged on him. I would not.”

“Does Your Highness wish our task ended?”

A tilt of her head under the weight of pearls and hair. A subtle smile. “We are, she said, very fond of plays. You were about to answer my question.”

I should ask for Ingrim’s head roasted and brought in on a platter with an apple in his mouth, and bits of boiled egg to make the eyes.“I was a guest of that same Thomas Walsingham when your summons found me,” Kit said carefully. “There were papers. Manuscripts. Poems, part of a play.”

“I am sorry.”

He believed her. “He has burned them. Better my life lost than my words, Your Highness,” Kit said. “There is nothing else I will be remembered by.”

She stared down her nose. “You will be remembered as a sodomite, a heretic, and a mediocre playmender who died in a cluttered tavern through a tawdry brawl over some free-looking young man’s favors. We pardoned your Ingrim Frazier, and we have buried your name, and we have saved your body and perhaps your immortal soul. Our Spirit’s cousin, the estimable Widow Bull, will be tarred as a feckless tavern wench, and all that will be known of Marley is that he was a shoemaker’s son who came to a sad and ugly end.” And then that smile, and a negligent wave of a jeweled hand. “You may save your thank-yous.” Every word a blow, and yet the logic galled like a spur against his skin.

“Widow Bull is Baron Burghley’s cousin? Your Highness! I did not know that.”

“She is also a distant cousin of the Queen of Faerie’s court musician.” Elizabeth’s smile broadened. “Twas she saved your life, sweet poet.”

Her delight was a schoolgirl’s, and Kit could almost smell stolen flowers when he met her eyes. “Thank you, Your Highness,” he murmured, and she laughed like a very young woman indeed.

“I knew it should come. Now beg your boon. The hour grows late, and old women kept from their beds wax querulous.”

She’d used and discarded him like a street-corner lightskirt, and still he permitted her to charm him. As if permission had anything to do with it.

“Your Highness. If it suits you, would you share what you know of the Mebd, your sister Queen?”

Elizabeth’s eyes widened: her only indication of surprise.

“A fair and clever question, Sir Christofer,” she answered. “And one I cannot answer with the rectitude that it deserves but I will send you as well armed into Faerie as I may, and hope you will remember your old Queen with fondness.” Her smile grew pensive under white lead paint and carmine. Dizziness spun him.

“I have been ever too fond with you greedy, extravagant boys. Our reign reinforces the Mebd’s, and so in subtle ways she supports it. The tricks you wreak with your plays have a greater place there than here, for her land is wove of the stuff of ballads and legendry. A strong Queen in England means a strong Queen of the Bless’d Isle, and she is old enough to know it. Old enough to remember Boudicca and Guenevere. But you have a problem, Sir Christofer.” She paced, pausing at last by the candelabra, and passed her hand through flames as if she caressed a lover sface. “Because it wasn’t the Queen of Faerie who knighted you and bedded you and took you into her service, was it? And when we’release you, it is not to her service you will go. And she is dangerous when thwarted, that one, and ambitious to a fault.”

“Morgan,” he said, understanding, as another spasm wracked him. “Was the soup poisoned? Does she want her sister’s crown?”

Elizabeth shrugged, and her eyes grew dark before she turned away. “Who can say what one Queen wants of another?”

“Who can say, indeed. I will never …” He stopped, and then found his voice again. “Great Queen …”

“Do not flatter me, Christofer. Tis boring.”

“Your Highness. You release me from your service.”

“We do.”

He bowed around the hollowness that filled his throat, though pain grew in his belly like a flame. I must return to Morgan,he thought, realizing the source of the agony suddenly. “Service is what I have borne you, Your Highness, for I have not known you. And now that I bear you no service, I find I do know you. And my Queen, for what a playmaker’s word is worth, I have traded that colder thing for a warmer thing, and with your permission, I will say now that I bear you love.”

“So many masks, Sir Christofer.” She raised one hand to her face. “We have that in common.” Her eyes narrowed as he broke, leaned forward, a cold sweat dewing his forehead.

“Your Highness,” he apologized, and she waved him silent.

“Gone too long from Faerie already, she sniffed. There’s a mirror in my chambers that will serve. Come, then. Lean on mine arm.”

“Your Highness. It is beneath your dignity.” But a bubble of pain silenced him.

Elizabeth jerked her chin, dismissing his protest with a gesture. “I am old and a Queen, and you shall do as you are bid. I will not have your life on my conscience after so much contrivance to preserve it!”

“Your Highness,” Kit answered. And for the last time in a short mortal life, obeyed an order from his Queen. She handed him through the mirror, an old woman’s exquisite fingers steadying him. The glass surface clutched like bread dough, then snapped away before it could tear; he tumbled through, striking his knees and hands on stone. When he pushed himself up he thought the Queen’s long hands had come with him. But no, it was a rasping voice, jingle of bells in flicking ears, a strong small figure propping him up. “Sir Poet?”

Puck. Kit struggled to a crouch, the agony in his gut receding. And didn’t understand why his next words were, “Where is Morgan?” And whence the twist of worry and lust that almost sent him back to his knees a moment after he’d toiled up off them?

“Oh, about her tasks, I imagine. Or in her rooms. The Mebd set me to watch for you. She thought you might need assistance.”

“I did,” Kit said, “but I found it. Morgan’s rooms—does Murchaud keep quarters here?”

The Puck’s lips compressed as if Kit had said something unwittingly funny, but there was concern? sorrow? in the droop of the little man’s ears and the set of his eyes. “Aye,” he said. “I’ll show you Morgan’s rooms. And Prince Murchaud’s. And the ones that will be your own.”

“Mine own?” It was a pressure. The beat of a wave. As if being gone from Morgan’s side had pooled behind a dam, and now all struck him suddenly. Gone? Kit, you bedded her not two days since.But gone was the word, and gone stayed with him.

“Aye,” Puck said. “The Mebd’s given you an apartment.”

“Would you like to Morgan,” Kit said, and it came out a whimper. God, what has she done to me, Christ, what has she done

“As you wish it.” Puck reached up to take Kit by the elbow. Kit thought he heard pity in the little Fae’s voice, but it might have been only the jingle of his bells. “The gallery over the Great Hall is by way of these stairs.”

Kit lurched up them half at a run, aware that Robin fell behind on purpose and watched him go, bells jingling. Kit found Morgan’s door as much by luck as memory, tried the latch, slipped within breathing like a racehorse.

Morgan. She sat before the window, embroidering. Her golden hands moved over and under the frame, chasing a silver needle, dragging threads of colors Kit could barely comprehend, through linen white as doves. She glanced up, pushed her stool back from the frame, and stood.

“Safe home,” she said, and he hurried across the floor to her, the iron nails in his boots ringing immunity. She met him halfway, sleeves rolled back from the linen of her kirtle, clad in a gown so antique Kit had only seen the style on statues and in tapestries. “Sir Kit.”

He hadn’t words. Something screamed betrayal in his belly. Christ. Christ. He couldn’t name it. She brought her arms up, laced them about his neck when he froze, suddenly, aching. Craving.

“My Queen.” She laughed, mocking, her black hair tossed over her shoulder, braided into arope to bind his soul. “Long and long since I heard those words,” she said. “Speak more.”

But words abandoned him again. He fumbled at the knots on her gown, tore cloth. Never like this and this is not me but she was lovely, oh, skin gleaming in the light that streamed through the window, thighs like pillars revealing a flash of Heaven’s gate as she stepped neatly from discarded clothing.

He had no words. For the first time in his life, he had no words. He couldn’t kiss her mouth. Couldn’t bear that intimacy. He dragged her into an embrace, teeth against her throat, half sensible that he first crushed her, scratched her against the embroidery and jeweled fixtures of his doublet and then slammed her to the wall, cold stone against his knuckles, her naked body twisting in his grip, her hair knotted in his fist. Christ. It hurt. He bloodied his hand on the rough stone dragging it from behind her, fumbled the points on his breeches, the warmth of her sex against his scraped flesh like a siren song. What am I doing? What

No, he was a juggernaut. Automaton.She whimpered as he tore at her shoulder with his teeth, tasted the salt of her tears, his tears, remembered a mouthfull of more blood than this and the pain of torture, rape, confession. He strangled on a scream he couldn’t quite voice, unlaced an erection he thought might just burst … Christ, she’s pliant and end his suffering, pinned her to the wall as she squirmed against the velvet and silk and rough decoration of his clothes.

No. No. No.

“Christofer.” A murmur. One hand, light on his collar. God. Almost a whisper. More of a groan. His hand cupped her sex. He might have been a statue. “Morgan.”

“Not yet.”

“What?”

He ached, twitched. Writhed toward her warmth…

“I’m not ready.”

“Oh.”

He stroked her breasts with bloodied hands. Caressed the curve of her belly, the amplification of her thighs. Fell down on his knees before her. Kissed the arch of her hips, the black-forested delta below. She tasted of vinegar, rosemary, honey. He wept. He made her scream and knot her hands in his hair, pulling until heat seared his scalp. When she gave consent at last, he took her there, on the floor by the window, her naked body arching against his black-velvet-clad one and she licked hot tears from his cheeks and laughed.