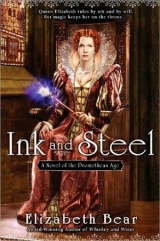

Текст книги "Ink and Steel"

Автор книги: Elizabeth Bear

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 24 (всего у книги 29 страниц)

A woman’s face with Nature’s own hand painted

Hast thou, the master-mistress of my passion;

A woman’s gentle heart, but not acquainted

With shifting change, as is false women’s fashion;

WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE, Sonnet 20

A tankard of Morgan’s brew bittersweet and redolent of ginger and lemons cooled by Will’s elbow. He dipped his pen in raven-black ink, so different from accustomed iron gall, and watched it trickle, glossy, down the crystal belly of the well.

“Stop playing with your pen and write, Master Shakespeare.” Kit curled like a goblin on the window ledge, wrapped in his parti-color cloak against the chill breeze through the sash. “Commit mine immortal words to paper.”

“Thine immortal words?” Will smiled. He touched pen to paper and let the ink describe the arcs and knots symbolizing Kit’s immortal words. “I was just thinking, we haven’t done this since Harry and Edward met their fates.”

“We’ve improved,” Kit answered. He turned his back to the window and kicked his heels against the wall. “I heard from Tom last night. Another letter.”

“And?”

“All is as well as can be expected. I’ll read it to thee later. When didst thou think to return to London?”

A little too casual, that question. Will laid the pen down and turned to regard Kit, silhouetted against an autumn light. “I’ve been here three, four weeks now? I thought I might stay another month, perhaps, and go home to Annie before Christmas.”

Will thought of Morgan, and the way his hand was steadier on the pen than it had been in years. He’d stay as long as he could. He tried not to think that once he left, the chances of being invited to return were slim.

“I’m glad of the company. And then there’s our Chiron.”

“I couldn’t leave that unfinished. Although it will never be performed in London. Difficult to find a centaur to play the lead.” Kit’s gaze unsettled Will. He looked down at the paper again. “I think it might prove a challenge even for Ned, if Henslowe still had him.”

“He’d be fine as Achilles.”

“He’d be brilliant as Achilles.” The pen wasn’t flowing well; Will dried the nib and searched out his penknife to recut it. He couldn’t quite forget the stiffness and hesitance in his muscles, but simply being better was such a blessing he couldn’t bear to question it too closely.

“We should give Dian a stronger role. Mayhap an archery contest. Don’t cut yourself, Will.”

“Very funny.” But he looked up and saw Kit’s concern was genuine, and looked down again quickly. “Archery would give us a chance to bring Hercules in earlier, and show him at play with his arrows.”

“Aye. Will.”

The tension in Kit’s voice drew Will’s head up. “We could still do Circe, instead.”

“Nay, Kit answered. There’s a thing that happens here, every seven years. A tithe.”

“The teind. Morgan told me.” No, no mistaking that flicker of Kit’s lashes when Will said Morgan’s name. Nor was there any mistaking the relief on Kit’s face when Will continued. “She said I am a guest, and needn’t worry; hospitality protects me.”

“Then you’ll stay; tis settled.” Kit braided his fingers in his lap for a moment, stood abruptly and began to pace, almost walking into a three-legged stool that Will had absently left out of its place. “We’ll be like Romeo and Mercutio: inseparable. What happens after the archery, Will?”

“Mayhap a philosophical argument. Chiron and Bacchus. We could trade off verses, give each a different voice.”

“And I suppose I am meant to versify Bacchus?”

The sharpness of Kit’s tone halted Will’s bantering retort in his throat. “If you prefer the noble centaur, by all means. Kit, what ails thee?”

Will saw the other man pause before he answered, the moment of contemplation that told him Kit was framing some bit of wit or evasion. But then Kit looked him in the eye and frowned, and said straight out, “I’m jealous.”

“Of Morgan?”

“Dost love her, Will?”

Will picked up his cold tisane and gulped it, almost choking. “Love is not a seemly word, where vows are broken.”

Kit’s lips thinned. “Grant I forgive thee for Annie’s sake.”

Will stood and crossed the room, crouched by the cold, dead fire. “Kit, yes. I love her.”

“Then I am jealous. Of thee, not Morgan. And canst swear thou feelst nothing of the like?”

Will stopped. Thought. Closed his eyes. I could lie. Could he?

“What I feel frightens me. I love thee. Is my love for thee less than thine for me, that I would kiss thee?”

“You’ve not held a rose unless pricked by a thorn, sweet William.” Will shot Kit a hard look; Kit’s eye shone with his silent cat-laugh.

Will spread his hands wide and swore, then: “Here.” He kicked the stool toward Kit, and tossed a roll of papers tied with ribbon at him. Kit more batted them out of the air than caught, but wound up holding the roll securely. “What?””

“Read.”

He turned his back on Kit, and the stool, and the golden Faerie sunlight that poured over both. The light illuminated Kit’s flyaway curls with the sort of halo usually registered in oils, dry-brushing the dark mulberry velvet of his doublet, making the crumpled sheaf of papers in his hands shine translucent. Will slapped wine into a cup perhaps over quickly.

“You may skip the first,” he counted on his fingers, “seventeen. Or so.”

“Starting from ‘Shall I compare thee’ …?”

But then Kit’s voice trailed off into the rustle of thick pages, and Will stared out the window over Kit’s shoulder and drank his wine without tasting it, small sips past the tightness in his throat, until enough time went by for the sun to shift and warm the rug between his boots. He didn’t dare look directly at the young man reading; surely Kit hadn’t aged a day in six years, but the calm expression of concentration on his face dizzied Will more than rejection or horror would have.

Finally, Kit looked up. “There must be a hundred of these.”

“One hundred and two. So far. Not counting those terrible ones I wrote for Oxford.”

“One hundred and two.” Kit cleared his throat, and read:

So oft have I invoked thee for my Muse,

And found such fair assistance in my verse

As every alien pen hath got my use

And under thee their poesy disperse.

“That says a dozen things, all different, half of them bawdy. These are wonderful, Will.”

“They re yours,” Will answered carelessly. He brought a second cup to Kit.

“I have perhaps been cowardly. These…”

Kit lay the papers on the floor and his cup on the windowsill, expression neutral as Will sank down on the floor nearby. Shades of red colored Kit’s cheek in waves. “I am not accustomed to being the subject of poetry.”

“Are we not as brothers? Like Romeo and Mercutio.”

Kit stood with a young man’s nimbleness and knelt in the same movement on the floor before Will, who set his cup aside.

“I should not use a brother thus,” he said, and knotted his right hand in Will’s hair, meeting Will’s gasp with a wet, swift kiss. A kiss that bore Will over, slowly, with perfect control, until he lay flat on the carpet, Kit straddling his hips. Kit’s lips moved on his lips, his cheek, his eyelids: a little tickle of mustache, the lessened ache and stiffness in Will’s muscles forgotten as he raised his hands to encircle Kit’s waist. Kit leaned forward, slick mouth wanton on Will’s ear and then his throat, until Will felt the flutter of Kit’s heart, the bulge of his prick, and the pressure of his thighs. The velvet covering his body was warmer than the sunlight.

“What of thy Prince?” Soft, afraid to startle Kit away.

“He is in no position to bargain for fidelity,” Kit answered, between kisses, deft fingers unfastening Will’s buttons in a manner that presumed no argument. “And I would rather thee than he, my heart, on a thousand stormy afternoons. Ask me to choose, Will.”

“I’ve no right,” Will answered, and swallowed around pain.

“Fear not,” Kit said, drawing back as if he saw the discomfort twist Will sface. “No harm will touch thee at my hand.” He stroked Will’s breast as if he could feel the rigidity in those muscles, locked so tight they trembled. Finishing the buttons, he began to unlace Will’s points.

“Love,” and Will closed his eyes as Kit quoted his own words back to him. “Then give me welcome, next my heaven the best / Even to thy pure and most most loving breast.” Kit was bent over him, Will saw when he opened his eyes again, and Kit’s hands were nimble at their undressing.

“This will require conversation, William.”

With a little shiver, Will identified the emotion that pinned him to the floor: it was fear, a cold knot of terror that blended with the honeyed rush of longing to render him helpless. “I am not certain I am capable.”

“Well,” Kit opened Will’s doublet and slid one rough hand under his shirt, letting his warm palm rest under the arch of Will’s ribs, “Will, you re too thin.”

“Aye,” he answered, at last able to laugh. “Too thin, undereducated, set above my station, and disinclined of writing the sort of masques and humors in fashion in London, for all Faerie loves me. Chapman or Jonson will be happy to tell you more of my failings.”

But there was a sort of magic in that unmoving hand. Its warmth spread through him and unlocked the chains that held him taut, unknotted the fear in his belly. Will let one hand slide down Kit’s leg, thumb caressing the inside of his thigh.

“Undereducated?” Kit leaned forward to claim another kiss. “I had promised to improve your understanding of classics. Shall we start with some Latin, then, before we move on to the Greek?”

“Think you my Latin insufficient?” Will opened his mouth for the kiss. Kit hadn’t touched his wine. His mouth was flavored with traces of pipe tobacco and the fainter bitterness that was just Kit. He stroked Will’s hair as if gentling the wild thing Will suddenly felt himself to be. Kit stretched like a cat while Will unlaced his collar and then stopped, as sunlight caught the shiny unevenness of old scars. Will pushed the edges of lawn apart and reached up to brush Kit’s breast with his fingertips, outlining a shape that had the look of a sigil in some arcane alphabet.

“Christ, Kit.”

“Ancient history,” Kit said, and kissed Will’s fingers. Thou’rt trembling. Art certain … ?”

“Aye,” Will said, and put his fingers through Kit’s hair. “I hate to think of thee…”

“Peace, Will. There’s less that’s pretty, I’m afraid.” Kit shrugged out of his shirt, biting his lip, refusing to meet Will’s eyes while they made a fresh inventory of his scars. And then Will reached for him, and it was all right, after all.

Someone’s foot scattered papers across the jewel-red wool rug, and mismatched scraps of parchment and foolscap crinkled and adhered to skin. Will laughed, and Kit bit his shoulder gently, sliding up to cover him. “Skinny and furry,” he said. “I apologize for the state of the poetry.”

“I needed to make a fair copy anyway.”

“The words could hardly be fairer.” A lingering kiss, fraught with intricacies. Will ran a slow hand up Kit’s spine, enjoying the abandoned expression that followed his touch. Fear filled his throat, but he said, “Thou offer’d to instruct me.”

“Tis not often I’m privileged to instruct thee.”

“Other than blank verse and buggery?”

Kit choked, turning his face aside until he mastered the giggles that warmed Will’s throat. “Buggery,” he recited, lips twitching with the effort to maintain a bored pedant’s tone. “So-called in reference to the purported practices of the Bougres, gnostics of France, who held the world so evil that procreation was a sin.”

“Kit,” Will interrupted, “surely you are the most erudite of sodomites.”

Kit wheezed laughter. “Been said.”

“Art … willing?” he asked when Kit’s shoulders stopped shaking.

“Willing and more than willing”

Will caught his breath. “Work thy will on thy William, then.”

Kit, regarding him seriously, touched the tip of his nose. “Still frightened?”

“Not enough to matter,” Will answered, and let Kit lead him to the bed.

Mortimer:

Why should you love him whom the world hates so?

Edward:

Because he loves me more than all the world.

CHRISTOPHER MARLOWE, Edward II

Much later, they dressed and trussed and sorted the scattered sonnets in silence and the morning light. Kit was concerned to see Will moving with stiffness as he crawled beneath a bench to reach out papers.

“Will … have I hurt you? Possibly we could have exercised more restraint but,” Kit’s lips twitched as he went to help, Carpe noctem, after all.”

Will sat back on his heels, holding a bit of foolscap in a hand that shook enough to flutter the edge of the paper. He laid his left hand over the right, as if to silence the trembling. “Tis just a palsy,” Will said. “Such as my father suffers, and one of his brothers had. It comes with aches and clumsiness, worse when I’m tired.” He smiled, then, and pushed himself to his feet. “And I am very delightfully tired. And thank you for it.”

“You’re young to be trembling, Will. Thirty-four is not such a great age.” The words seemed to swell until they stopped Kit’s throat, and he could neither swallow nor speak past them. His fingers tightened on the sheaf of poems in his hand as the meaning of the words came plainer.

Presume not on thy heart when mine is slain,

Thou gav’st me thine not to give back again.

Will handed papers to Kit, which Kit took to the table they shared. Shared.

Tis a fancy, Marley. He leaves thee soon. To return to London and his wife, and even here, he is not thine alone. Oh, but it was a pleasant fancy. And thou wilt outlive him, too. But not in name, an he’s writing poetry like that.

“Will you lie to me?”

“Fear not. Morgan’s helping me. And I’ve decades left,” Will answered, and let his shoulders rise and fall in a shrug as he stood. “More, if like my father. Well, tis not a bad death. The trembling grows, and the body perishes in the end for want of breath. Sir Francis died far worse. And I might still, on the path I walk. If Oxford has his way.”

Decades.

That time of year you mayst in me behold

When yellow leaves, or none, or few, do hang

Upon those boughs which shake against the cold

“Your poems don’t speak of decades, love. If I have mine,” Kit replied, and lifted a candlestick to weight the poems. “Gloriana will protect you. But come. This is not an hour for such thoughts.”

“No, Will said thoughtfully. It’s an hour for breakfast, I think. And perhaps I owe Morgan a little groveling.”

“Does she expect your attendance every night?” Kit regretted the words as soon as they left his lips, and fetched Will’s boots to cover his discomfort.

Will laughed, paying with a kiss as he took them from Kit’s hand. “No. But I rather suggested I would meet her for supper. And she no doubt thought to find me this morning.”

There had been a tapping at the door a little after sunrise, which had not awakened Will and which Kit, roused by dreams, had ignored as unworthy of the price of lifting his head from its throne on Will’s shoulder.

“Well, we can’t hide here forever, living on love.” Kit sighed and shrugged, his doublet settling onto his back like duty. “I suppose tis brave the day and regroup when the enemy gives up an advantage.”

“I’ll see you at dinner,” Will said. “And then this afternoon, more centaurs.”

Kit opened the door, turned back, and smiled. “And satyrs?”

“Christ,” Will grumbled, following. “A little pity on an old man.”

Kit laughed as he left, bracing himself for the knowing smiles that certainly would greet his and Will’s simultaneous reappearance after eighteen hours of silence and a locked door. Things were different in Faerie, aye; for one thing, the gossip galloped three times faster. He picked his way down the stairs, one hand on the railing, as Will went up, and tried not to frown. Trouble thyself not with that thou canst not command. Thou lovest, and art loved. Twill serve.

Breakfast had no more formality in the Mebd’s palace than it had at Cambridge or in a shoemaker’s house in Canterbury, but Kit had paid in two missed meals for the pleasure of an uninterrupted afternoon and evening, and he made haste to the hall in the hope that there would be bread and butter and small beer left. The tables had not been cleared for dinner, but there wasn’t much left to choose between. He piled curds and jam on thick slices of wheat bread with gloriously messy abandon, balancing two in his left hand and the third atop his tankard until he found a place at a crumb-scattered trestle and fell to with a passion. He was halfway through the second slice, leaning forward over the board to save his doublet the spatters, when a shadow fell across the table. He looked up, chewing, into Morgan’s eyes and swallowed hastily.

“Your Highness.” Her smile had a flinty glitter as she hiked up her skirt and stepped over the bench opposite. “Sir Christofer. I see you’re in good appetite.”

“I missed my supper. Will was looking for you just now.”

“I shall seek him. I trust you had a productive evening…”

“Most.” Oh, that smile. Deadly. She helped herself to his tankard, sipped, and frowned over the beer before pushing it back at him. Kit never dropped his gaze as he drank.

“One can send down to the kitchens for a tray, if one is indisposed. If one wishes the distraction.”

“Poetry waits for no man.”

Now she gave him a better smile. “And was it poetry?”

“Of the sheerest sort.”

“I expect you shan’t be calling upon me this morning, in that case.”

“Now that thou hast had thine use of me.” The wrong tack; Kit tore bread with his teeth and swallowed more beer, giddiness in his newfound power. “Consider all debts paid for the use you had of me. Touch.You won’t take him from me, you know.”

A possessiveness he wondered if she’d ever shown over him flickered across her face. The jealousy he’d thought well-sated flared, and he chased it down with beer.

Must she own everything she touches?

The question was the answer. “Madam, he is a married man, with a home and children. I won’t see him bound to you.”

“No? How will you stop me? If I offered him surcease from pain and a place in Faerie at my side? At your side too, Kit. Help me. He’d half like to stay here. He wouldn’t deny us both.”

Will. Here. Alive, not ill any longer.

“He’d have to become like me. A changeling.”

“An Elf-knight, Sir Kit. Where’s your blade, I wonder?”

“In my room. An Elf-knight? And yet you wear your rapier wit.”

She shook her head. “What else did you think you were become? Help me, Kit. Help me save your true love’s life.”

Oh. Oh. He thought of Will’s hand shaking. Knew Morgan had been waiting, lying in wait, and this was the opportunity he’d given her. Closed his eye for an instant, and covered his mouth with a hand that smelled of sugar and blackberries. And damn his soul? He watched her face, the thin line between her crow-black brows, the way her eyes went green in passion and the mounting morning light, and realized he’d misjudged and misunderstood her again.

“Morgan.” She startled at her name, and at the tenderness in it, which startled him as well. “Wouldst take his family from him, my Queen? Bind him as thou hast bound Marley, and Murchaud, and Lancelot, and Arthur? Should the list of names continue? Accolon, Guiomar, Mordred, Bertilak. How many great men hast thou destroyed?”

“How many have I made greater than they were? How many have I healed and defended? I am not merely that evil that thou wouldst name me, Christofer.”

“Morgan,” he said, understanding. He took her immaculate hand and cupped itin his own. “I know what thou art.”

She blinked. The tone in his voice held her; the revelation un-scrolled. “Thou art that which nourishes and destroys: the deadly mother, the lover who is death. Because that is what we have made thee, with our tales of thy wit and sorcery. Thou art too much for mortal men to bear.”

She sighed and sat back, but did not draw her hand away. “Wouldst see him die?”

Kit stuffed another piece of bread into his mouth with his left hand, refusing the bait. “Morgan. You re a story.”

“Aye, Master Marley. Poet, Queen’s Man, cobbler’s boy,” she said. “I’m a story. And now, so art thou.”

He sat back. He would have let her fingers slide out of his own, but she held him fast and looked him hard in the eye. “A story who’ll live to see his mortal lover grow old and gray, totter and break. Canst bear it, Kit? Canst thou bear to see that light extinguished in a few short years?”

He shook his head. “No. I cannot bear it. But I rather imagine Will couldn’t bear to bury his son, either. And Morgan, I will not see him owned. Mortal men are not meant to live in your world; we cannot bear that either.” Heads were turning around the hall at the intensity of the whispered conversation, the white-knuckled grip across the table. Kit breathed deep.

“Morgan. Tis true what I say.”

“Aye.” And it was a curse when she said it, and her eyes were blacker than he had ever seen them. “I was a goddess, Kit.”

“Madam,” he said with dignity. “You still are.”