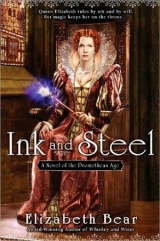

Текст книги "Ink and Steel"

Автор книги: Elizabeth Bear

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 16 (всего у книги 29 страниц)

She wore no gloves, for neither sun nor wind

Would burn or parch her hands, but to her mind,

Or warm or cool them: for they took delight

To play upon those hands, they were so white.

CHRISTOPHER MARLOWE, Hero and leander

Kit and Amaranth strolled together through the airy corridors of the Mebd’s palace, her coils dragging behind like the train of a queen. He walked with a flute in his hands, practicing the fingerings, keeping the lamia on his left side where he could see her hair writhing.

“You should make a start on your cloak, she said. I would help you sew the patches.” He wondered how she spoke so clearly, when her forked tongue flickered with every breath. Magic and more magic.

“Cairbre says I must stitch them myself. Tis part ofthe protection.”

“Then I will teach you to sew.” Lightly scaled fingers demonstrated a minnowlike dart. Kit frowned, not looking up. “I am,” he said with asperity, “a cobbler’s son. I can handle a needle very well indeed.”

“So I’ve heard rumored.” She laughed when he shook his head. “Tell me of this protection. I haven’t heard the tale.”

“The Queen’s Bard wants me for an apprentice, I think. A true one, and not a hanger-on. It seems to involve rather a lot of memorizing antique ballads. They were great memorizers of all things, the Druids. They would have gotten along well with my latin tutor. I wonder if the Druids also believed in the recollective power of birchings.” He slid the flute into its case on his hip opposite the rapier, and stretched his fingers one against the other. “I am restless, lady Amaranth.”

“You have seemed less anguished of late, Sir Poet.”

“I have. I am busy playing the student again, and making poems to please the Mebd. Morgan leaves me alone, more or less. Is pleasant when I report to her, and gives me no hint to what use she puts mine information, or if it is of use at all. Will not answer my questions about Murchaud, and neither will the Queen. And there is no news from England.”

“leave it, Christofer. England is done with thee, and thee with she. How is it that writing for royals is not so rewarding as the bloody rush of the common stage?”

“I should be writing,” he said, aware as he spoke that Amaranth’s last few comments had fallen into silence unanswered, and he could not recall them.

“Ah,” she said. Something in her cool, melodious voice caught him; he turned to study her eyes.

“Such a lovely man,” she said, stroking his cheek. Her fingers felt like cool leather, the scales catching his rough-shaven cheek. “Pity about your scars.”

“There’s nothing to be done for it,” he said. “Many a man’s survived worse than half a blinding, and to more sorrow.”

“What would you do for your sight returned?” she asked, as if idly.

“Can you do such a thing?” She shook her head. “There might be those that could. It’s in the songs: If I had known, Tamlin, that for a lady you would leave, I would have taken your eyes and put in dew from a tree.”

“I do not know that song. Cairbre has not taught it me.”

“We do not sing it here.” She smiled, a curve of bloodless lips.

His footsteps padded beside the rustle of her belly sliding on stone. “It has not been written yet. And what would you write, if you were writing?”

“A play. Something of Greek descent, perhaps. Has ever a playmaker had such a cast as here, that could play satyrs and centaurs convincing?”

“A tragedy?”

“Tis what I’m good for. Tragedy and black farce.” He ran the fingertips of his right hand along the wall, feeling slight dimples between the cool stones. “You know much of my history, lady Amaranth. And I know little of yours.”

“I have no history.”

As they turned the corner, the way opened wide. Cushioned benches lined the windows on the west wall; on the east were glass doors made of a thousand diamond-shaped panes as small as Kit’s palm. Beyond them, sunlight lay on autumn gardens, begging comparisons to Elysium.

“Shall we wander?”

“I know why you are overset, Sir Christofer.”

“I never said I was unhappy.” But he held the door for her, waiting until the last slender inches of her massive tail whipped past, and stepped out onto the balcony behind. Amaranth rose like a charmed cobra, the power of her lower body lifting her human torso fifteen feet into the air. She draped her coils over the thick stone banister and stretched down it, scorning the steps Kit descended. He enjoyed watching her move; she didn’t slither side to side, like a garden snake. Rather, her scaled belly pulsed in ripples like waves rebounding in a fountain, pushing her forward, leaving not so much as a depression in the gravel path to mark where she had gone.

“Neither did you say you were not,” she replied, stretching her arms to the sun. The snakes of her hair yawned wider than cats and twisted sleepily in the warmth of a St.-Martin’s-summer day, tiny fangs glittering white.

“Clever Amaranth. Snakes are a symbol of wisdom.”

She turned to him, winked one of her expressionless eyes.

“If you’re so wise, then what is it troubles my well-known, imperturbable calm?”

Her laughter was a hiss. “The Prince-consort, of course.”

“I have not seen him” … Kit paused. “Time in Faerie, ah. I cannot say how long it’s been. Years.”

“Then you have not been informed. Curious.”

Without inflection, as she sank her face into the enormous, late-blooming starburst of a peony. Kit turned so fast that he tripped, his throat closing in fear. Some detached, intelligencer’s fragment of his mind observed his sudden panic wryly.

“So. It was not all enchantment, was it, Sir Christofer?”

“Been informed of what?”

She cupped the blossom in her hand as she rose like a pillar to face him, so its crimson petals shredded and scattered through her fingers.

“He has returned.”

“No. No, I had not known. When, lady Amaranth?”

“Two days gone. He’s been closeted with his mother, and then his wife.”

“But I would have thought”…

Kit rubbed his eyepatch. “So would I,” he said, cold between his shoulders. “I would have thought, as well.”

He hadn’t a key, but locks as ancient and massive as the one on Murchaud’s chamber door were a formality, a politeness more than a measure of security. He almost could have flipped the pins from the tumblers with his finger; a shorn quill and the shank of a heavy brooch sufficed. Kit sprang the lock and glanced over his shoulder to see if anyone had noted his unorthodox entry. It seemed unlikely. He slipped inside and let the latch click tight behind. Twilight filled the bedchamber. Such decadence, in Faerie; even servants slept in their own beds. The first time in his life that Kit had had a bed and a room to himself was at Chislehurst, and that was a function of Tom Walsingham’s great house understaffed and underoccupied.

Kit walked to the window and threw the panes open, leaning out over the broad carpeted ledge on his elbows and breathing deep of the sweet air of Faerie. The sun had slid under the horizon, and mackerel clouds banded a violet sky. Dying rays stained the misty tops silver as mirrors: their bellies gleamed pewter-dark. A tiny knot had snagged in the carpet. Kit worried it with a thumbnail, as if he could press it back into place among the red– and black– and mustard-colored wool. The evening smelled of rain, but only change-of-weather clouds hung across the sky. Kit at last closed his eye and leaned his forehead on the back of his fingers, thinking about what Amaranth had said. A remembered taste of blood came with the thought of a glittering blade, poised just above his eye He pressed the heel of his hand against his eyepatch. How long can you play invulnerable, Kit?

He drew one last breath and turned from the window. First, Murchaud’s correspondence. And then …

And then whatever follows.

Night was long fallen when the turn of a key in the lock woke Kit propped upright against a bedpost with his naked blade across his knees from a doze. He opened his eye on darkness and rose to his feet, groping his way by the edge of the mattress. No servant had arrived to kindle a fire; perhaps the locked door had been barrier enough. Murchaud entered alone, bearing a flickering lamp. Kit recognized the turn of his head and prayed himself invisible against the bed curtains as Murchaud pulled the key and locked the door behind him. The flutter in his throat was excitement and apprehension, nothing more. The memory of Tom and Audrey companionship, conversation, family unoccluded by sorcery or betrayal, still burned brighter than Murchaud’s presence. Kit swallowed against the feeling that he betrayed them, somehow.

You’ll never see them again. This is Faerie. There is no love here. Use what you have.

Murchaud set the lamp on a stool and unbuttoned his doublet at the collar, turning toward a wardrobe cupboard against the interior wall. Kit moved across the carpets soundlessly and as Murchaud hung his doublet on a peg set the tip of his rapier between Murchaud’s shoulder blades, just a half inch to the left of his spine. Kit remembered the spring of ribs, the curve of muscle under his hand, and pressed forward until the point of the blade slid throughsnow-white silk and a stain the size of a shilling started up.

“If I blotted a pen,” Kit said softly, “why should I not write my displeasure on your skin?”

“No reason,” Murchaud answered, lifting both hands into sight. “As welcomes go, this is more dramatic than most. Might I unhood the lantern, or do you plan to kill me in the dark?”

“Only if you wish to die tonight.” Kit stepped back, sword whispering into its sheath in a snake-tongue flicker.

“What sort of a death are we discussing?” Murchaud’s long fingers darkened the lantern for a moment and then were silhouetted; Kit looked down to avoid sudden brightness. He ran his tongue along the back of his teeth before he answered.

“Thou couldst have told me.”

“Told thee which?” Murchaud came toward him, as if to pull him into an embrace. Kit turned aside, feeling unfaithful still, and not to Murchaud. He went to the window and flung the sash open, leaning out into the night. A cold moon gilded the lawns and gardens below, tossing thoughtfully on the ocean. He did not turn back when he spoke.

“Hell, Murchaud?”

“What dost thou mean?” The voice close behind him, Murchaud’s footsteps soft as a breeze. A hand on his shoulder, fingers brushing his throat.

Kit smiled, and didn’t shiver. “Thou hast been, what, five years in Hell? I know thou didst write to thy mother and thy Queen. Yet not to me.”

“I thought …” Murchaud halted. “My mother worked a particularly vile sorcery on thee.”

Kit snorted and shook the hand from his shoulder. “Thou claimst to be a friend to me? Thy pardon, dear heart, if I mock the claim.”

“Tis true.”

“Tis words. Kit moved away. He leaned against the wall between tapestries and crossed his arms, watching Murchaud spread his hands in conciliation, all the night and the nighttime sea behind him.

“Just words.”

“How didst thou know?”

“Know that it was only words?”

“Know I was in Hell.”

“A man has ways,” Kit answered. And he was assured that he had set Murchaud’s memorized papers back in order so neatly that no one would know they had been riffled. “Thou didst travel to negotiate the tithe. The seven-year’s teind.”

“We will need Hell’s protection as much as ever we have when Gloriana passes.”

“What of thy Queen?”

“What of her?” Murchaud let his hands fall to his knees. “Marriages are what they are, and politics are what they are.” Surely and the note of pain in his voice was masterful: so little, so bright, and so manfully repressed that Kit could almost believe it.

“All that love thou didst show me was not merely black magic and bindings?” Almost believe it. “All that love?” Kit smiled, and reached down with his left hand to slip his scabbard from his belt and lean the sword against the wall. He came to Murchaud, and ran his fingers through the other man’s jet-black curls, lips so near to lips that Kit could taste Murchaud’s breath, with a trace of wine on it, and a scent like roses.

“All the love I have given thee in subjugation is but shadows of the love thou shalt have. We keep nothing, who serve.” And he pressed Murchaud’s head back against the window frame and kissed him as if Kit’s mouth were a branding iron and Murchaud the property it marked.

Kit did not ask himself to whom his service went. And it was he who rose from the warmth of the bed in the darkest hour of morning, retrieved his sword, and dressed. And turned the key in the lock. And left.

There were mirrors in Faerie, after a fashion: glass, water in a bowl, wine in the bell of a glass. Morgan had not precisely been truthful in saying there were none. What was true was that they did not reflect. The Darkling Glass drew all reflections to itself: into its embrace, and into its power. All reflections save those in a blade. A silver dagger polished to mirror brightness gleamed on the marble mantel over his fire, which lay as cold and unkindled as the one in Murchaud schamber. Kit stripped to his shirt and washed in cold water from the ewer beside the bed. He rinsed his mouth and spat, combed his hair, and went to throw the window wide so the autumn nighttime could fill his chamber. Which is when the light dancing in the polished blade of that dagger caught his eye. A light he hadn’t seen in …

How long?

He left the window open and walked toward the dagger, which glittered as if reflecting the light of a single candleflame. Will, Kit whispered. How long has it been? He lifted his hand toward the thick bundle of papers that lay beside the blade, visible in shadowy outline. A letter, he knew, with his name written on it in Will’s fast-scrawled secretary’s hand. Set on the mantel before a mirror, with a candle lit beside it. News of Robin, perhaps. Mary, Chapman, Sir Francis, Tom. England. The Queen. The papers were insubstantial, glimmering like shadows: a reflection cast on air by the light in the dagger’s bright blade. If Kit’s hand touched them, they would appear in his grip, firm and crumpled. He reached out and willfully tipped the dagger over. The light in the blade died as if snuffed. The bundle of papers flickered like a blown candle andvanished. Kit bit down until he tasted blood, and took himself to bed.

Gloucester:

O, madam, my old heart is crack’d, it’s crack’d!

WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE, King Lear

The house was dark when Tom Walsingham’s carriage rattled to a stop on the summer-baked road. Will put his foot on the iron step, clinging to the door for support as lathered horses stamped.

“There’s an inn not far, John.” The coachman tipped his cap. “I know it, Master Shakespeare. I’ll see to the horses and I shall find you tomorrow.”

I am grateful. Will would have tipped the coachman—another man’s servant, after all but John clucked to his horses, gentling them into the twilight as if he hadn’t seen Will’s outreached hand. It was a measure of the trust of the horses that the coachman never reached for the whip, and they went willing though their hides heaved like bellows. Their clatter receding, Will turned toward the thatched and half-timbered cottage as swaying exhausted as if he had run from Kent on his own two legs. The door was latched, painted wood tight against timbers set in stucco that gleamed a soft pink-gray, stained with ochre earths. Anne had let the flowers by the doorstep die. Will tugged twice to free the latch, although he knew before the door opened that his house was empty: no smoke rose from the chimney, and he could smell cold ash. Twilight streamed down from the loft. Annie had left the windows under the eaves unshuttered.

He fumbled his habitual shilling as he stepped inside, the glass-smooth coin ringing on the door stone. He crouched to retrieve it, feeling among the rushes strewing the floor, and suddenly found he had not the strength to stand. Cold silver between his fingers, he crouched on the threshold in the open doorway and buried his facein his hands. It was Edmund who found him. Will had curled forward, his knees drawn up against his forehead and his back pressed to the timber. He heard the footsteps up the walk and looked up, blinking in the twilight, scrubbing a hand across his face although his eyes stayed dry.

“Will. You should have written you were coming.”

“I got here faster than a letter would have,” Will said, and covered his mouth as he coughed. “From Kent. We only stopped to rest the horses. Where is Annie?”

“With Mother. Are you … ?” Edmund’s voice trailed off. Will pushed himself to one knee and stood.

“No, I’m not well. How did you know to find me?”

Edmund took Will’s elbow as Will hid his shaking hand in his sleeve, the shilling folded tight inside his palm.

“Bill the landlord had it from your driver. He sent his boy. Come.” Both men pretended it was exhaustion alone that left Will leaning on his brother’s strong young arm. “Let’s go home.”

He dreaded Anne. Feared anything she might be speaking, unspeaking. Eyes black with weeping. Eyes cold with consideration. Was there anything I could have done? If I had been here, surely’t were something I could have done.

She sat by the fire when he came into his parents house, her dress overdyed drab in black that would fade as one might expect mourning to fade: eventually. One expected to lose babies. Or young children to the flush of their illnesses, the measles and the scarlet fevers and the great and smallpox. Will’s parents had lost three girls before Will, one of them the first Joan of two at nearly Hamnet’s age. Children of schooling age, however, an only and an eldest son …Will didn’t notice if Edmund came through the door with him. His father might already be abed; Susanna and Judith were nowhere in sight. Will’s mother left her darning in a pile on the board and came around it, past Annie, who looked up, but no more than that. Mary Shakespeare squeezed her own child’s shoulders and leaned her forehead briefly on his neck. She kissed the cornerof his mouth. “Oh, Will”

Her voice broke and he clutched her tight for a moment, then set her back the length of his arms.

“Thank you.”

She nodded and ducked away, knuckling her eye, a hasty clatter on the stairs telling her passage. Will went to his wife. Annie’s hands were white on her skirts. She crouched on a three-legged stool as if warming herself before the fire, but Will knew her chill would take more melting than that. He knelt down before her. The stool wobbled under her when he took her hands, the one leg shorter than the other that his father hadn’t mended in fifteen years gone past. He opened his mouth; she closed it with a look.

“You came,” she said. She leaned forward, her unbound fair hair falling around him, tangled with her lack of care.

“Would you doubt it?” Her look was answer enough.

“Annie, what happened?” She lifted her shoulders and shrugged. The hasty dye at her collar had rubbed off onto the linen of her smock. Her palms were calloused enough to rasp his skin, no lady’s white soft hands.

“Fffuh,” she started, and her throat must have closed on the words. Will heard the front door latched; no one spoke. A stealthy creak that was Edmund climbing the stairs to bed. Saving candles, Will wondered, or too weary still with grief to face a long evening in company? He held his peace and held Annie’s hands, and she neither flinched nor closed her eyes.

“Fell,” she said again, more clearly, leaning back on her stool until only his grip held her upright, their arms taut between them like a rigging. “Fell from an oak. Dashed his brains upon a stone.”

“Annie.”

“Hush,” she said more clearly, and shook her head. “If you had been here …”

Each word might have cost her blood. Will clutched her hands in terror.

She continued on a second breath.“… nothing would have changed.”

“Annie, my love,” he said as the tears silenced her, finally. “Come upstairs.” He pushed a tangle off her cheek. “I’ll brush your hair.”

“Will, come home.” She stood when he tugged her upright, leaning heavily on his arm. “I am home… .”

“Or let us come to London.”

“Plague,” he said.

She stopped, one foot raised, and pivoted toward the hearth, drawing him. “We should bank the fire. Everyone’s abed.”

Will crouched on the sun-warm hearthstone. The poker had a curved point on the back like the beak on a halberd; he raked coals together with the edge and knocked ash over them, and the last bit of a log that had fallen out of the fire. He stayed there, hiding his right hand between his knees, fingers steadied by the twisted iron handle. Warmth bathed his face, his fingers, warmed his breeches until he felt the weave of the cloth.

Annie reached down and pulled his right hand into the light. “Worse?”

“No better,” he answered, drawing the poker back so it scraped a white line through ash and across the stone.

Annie flinched. “You re thin.”

“Eating’s…” He pressed a hand to his throat. “Hard. And there’s famine in London.”

She swallowed and leaned closer. “Stratford as well. I wish thou wouldst have a care for thyself.”

“I am taking care of myself, Annie.”

“Shall I warm you a posset before we go up?”

“I subsist on the things,” he said. “I wish only thy company. Let us to bed, wife.” He hung the poker on the rack, muting the clatter with his hand, and thrust himself to his feet. She swayed as he slid an arm around her waist and drew her against his side.

Upstairs, he petted her until she slept; she rarely cried, his Annie. Even when he thought she better might. And held her until a sliver of moonlight fell through the shutters, revealing the dark hollows bruised like thumbprints under her eyes, and she rolled away to bury her face against the wall.

Will rose in his shirt and smallclothes and crossed the floor. Breathless warmth surrounded him as he threw the shutters back and leaned out over the garden, imagining the colors of the late-summer blooms whose nodding faces reflected the flood of moonlight thistle, daisies, and poppies. The Dutch bulbs would be over, but the too-ripe scent of late honeysuckle lay on the air like the scent of rot, and Will drew his head back inside.

Someone, Edmund? had carried his bags up the stairs. Must have retrieved them from John the carriage man at the inn. Will lifted the smaller case and dug in it for paper and pen, finding first the sealed and bundled pages of his uncollected letter to Kit. He pushed them aside to uncover his ink horn, silencing the rustle of papers as best he could, and left the case standing open when he went to the window. The moonlight was bright enough. He wouldn’t need a candle. Will laid his sheets on the ledge and worked the plug out of the ink horn before sliding the nib inside. He let the excess ink ooze back into the palm-sized container, propped it against the edge of the window, and hesitated, the quill almost brushing the creamy sheet. A Midsummer Night’s Dream,he thought, remembering the impossible blue of Lucifer’s eye. I’d dream myself home safe in bed, and Hamnet clattering down the ladder to shake Annie and me awake

The ink dried while he watched the moon-silvered garden. He dipped again and set it to the page in better haste, and wrote:

Ill met by Moone-light, proud Tytania …

Will drowsed, half waking, and mumbled as Anne smoothed his hair back to let the sunlight rouse him. The morning was unkind to the weary lines around her eyes. “The household is awake.” The clatter of pots confirmed it. “How was your sleep?”

“Broken.” He sat upright to knuckle the crusts from his eyes. He swung his legs over the edge of the bed. “Show me the grave today, Annie?”

She hesitated, reaching for her kirtle. “Of course. We…”

“What?”

“Thy father had a mass performed.”

“Christ, Annie, I don’t care what religion my boy is dead in.” It came out sharper than intended, but she didn’t flinch. Her brows rose, as if she were about to deliver a tongue-lashing, and her mouth opened and shut. She covered her eyes.

“Will, I’m sorry. It was hard, that thou wert gone.”

“Would that I had not been. Would that none of this were necessary at all. Would that I were still in Kent with lord Hunsdon’s Men. Would that I could have taken…”

“Stop it, Will.”

“I’m home now, Annie.”

“For how long?” She turned her back on him as she wriggled into her petticoat-bodies. Annie waited long enough to be certain he wouldn’t answer, and turned over her shoulder.

“That traveling priest is here more than you are, Will. If he were Anglican, I’d say I should have married him.”

“Traveling priests and cottage intrigues,” he said, lacing his points with hands that almost didn’t tremble. He heard her indrawn breath and rolled over it, refusing to look her in the eye.

“I would not fight with you, Annie.”

Her shoulders went back and she whirled on him, whispering so her words would not carry. “Well, and what if I would fight with you, Master William Shakespeare? Or shall I put that want on the shelf with all mine other wants, and will you talk to me of duty?”

She leaned forward, hands on her hips, her hair still unbraided and tangled over her shoulders. The little room seemed even closer as she stamped one bare foot among the rushes and then threw up her hands in exasperation at his silence. He felt as if he might choke on all the things he could not say to her.

“Annie, my love.”

“Go back to London,” she said, and turned away to open the door. “If your plays are more to you than your children. Go.”

“It’s not …” he began. But the door swung softly shut behind her, and Will let his mouth do the same. Damn, he said, and narrowly avoided punching the wall.

A sunny afternoon followed Will from the graveside. Fleeing its relentless cheer, he pushed open the door of Burbage’s Tavern and nodded to the landlord in the cooler, airy common room. “Good day, Bill.”

“Will.” He hesitated, a rag in his hand, and cleared his throat. Three or four other men sat about the lower level of the tavern, the silence hanging between them redolent of an interrupted conversation. “I’m sorry.”

“We re all sorry,” Will said into the heavy quiet. He nodded up the smooth-worn wooden stairs. “Have you anyone at work in the gallery today?”

“Not until suppertime. Sit down over here.” A gesture at one of the long trestles, flanked on both sides by sturdy benches. “I’ll see you get some dinner, for all the bread’s gone cold by now.”

“They fed me at home,” Will lied, taking a seat in a sunbeam, which caught flashes of silver from the coin that he fussed. He couldn’t face choking down bread and cheese before these pitying men.

“Ale would go kindly. Served warm, and in a leather cup.”

“Ale it will be. Is there news from London, Will?”

Will shrugged. “There’s starvation in the streets, want and privation, consumption and plague. The usual, only worse.”

“Preserve us from cities.”

Footsteps from the more occupied corner of the tavern, and a voice unexpected enough to knock the shilling from his fingertips to clatter on the trestleboard. “Oh, Master Shakespeare. Surely if London were so unhealthy as all that, none of us city rats would ever return, given a view of the country and a breath of fresh air.”

Will held the mouthful of ale until it could trickle past the tightness in his throat. He laced his fingers under the table and let the silver spiral, jingling, to a stop.

“Master Poley,” he said, and didn’t look up. “What brings you to Stratford?” Expecting the easy charm, the intelligencer’s lie. Surely Poley wouldn’t try to start an argument here, surrounded by Will’s childhood friends and his family’s neighbors.

“I came to look in on your family,” Poley said, swinging a leg over the bench opposite Will. “I’m a father myself. It seemed the least I could do, considering the care you’ve taken of Mary. And little Robin, too.”

Will did raise his eyes then, and dropped his voice. “Am I intended to understand this as a threat?”

“Understand it as you wish.” Poley’s trustworthy smile turned Will’s stomach. The intelligencer held up a pair of silver tuppence to catch the landlord’s eye, and traded them a moment later for a cup of wine.

“Have you considered how much your family must miss you? How much the worst it would be if anything should befall you in London, so far from home? Cities are dangerous.”

“And your family? Do you consider the future of your son?”

Poley just smiled, and it struck Will like a kick in the gut. I am not like this man. I am not like this man. But how, then, do we differ?

Will unlaced his fingers, lifted his tankard with his left hand, and only touched the ale to his lips. He wiped his beard to cover the smile.

“My wife may curse me to my face,” Will said. “And I can’t deny she’s a reason to. But neither my Annie nor your Mary will cross the street not to catch mine eye.”

“My Mary?” Poley turned his cup between the flats of his hands, scraping the board. “I haven’t a virgin thought in my head. Many a cheerful one, but not of Mary. Take her.”

“Tis not so.”

“Pity for thee, Will. She’s a wildcat.”

“I’ll not be thee’d by thee, either. Master Poley.”

“Ah.” The shilling lay shining between them. Poley picked it up, balanced it on edge.

“An old one. A toy. Too debased to spend. It rings fine.”

“It’s shaved to half its size,” Will said, as Poley made it jingle against the table again, the note of silver bell-clean.

“But the loyalty it buys is a whole loyalty, no?”

“Your point, man?”

A scrape as Poley pushed the rough bench back, quaffed his wine and stood. He extracted a short knife from his belt and pared his fingernails over thetable. Will edged his cup away.

“Mine only point is this.” A flick nimble as a cutpurse’s razor. Poley wore hammered rings on both thumbs, rings that glittered the dark hard radiance of steel. “You made an enemy in Essex.”

“My clumsiness is renowned.”

“A wonder you can stay on a stage at all but no matter. Think hard, Master Shakespeare.”

“Think on what, Master Poley?”

“Think whether your family might be better served by your return to Stratford. Or by your choosing a master longer for the world than lord Burghley. Or lord Hunsdon. Or Tom Walsingham.”

“Tom’s young.”