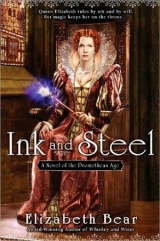

Текст книги "Ink and Steel"

Автор книги: Elizabeth Bear

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 13 (всего у книги 29 страниц)

Kit’s head came up, and otherwise he froze motionless against the trunk. A footfall, perhaps something as simple as a wild pig or a stag. Another crunch, and then a third. Hooves, he decided, the sound too crisp for a booted foot. He held his breath, hoping to see a stag or a hind and not wishing to disconcert a boar, if that was what minced toward him through last year’s leaves.

Well. Not a stag, exactly, but the stag-headed adventurer whose poise and casual grip on his sword had so arrested Kit’s attention on his very first night in Faerie. He dressed richly, an animal’s smooth throat rising from the collar of his doublet, some Gyptian god made English. The stag drew up, a brief rustle accompanying his cessation of motion. His finely etched head went back as if he considered flight, warm sunlight gilding the velvet of new antlers.

“Sir Christofer,” he said, and just as Kit was about to swing to his feet and remark on the unlikelihood of such an encounter, the stag pawed the earth and snorted. “I’ve been seeking you.”

“Seeking me?”

“Aye, Sir Christofer. Who else would be in the forest at this hour, save bogeys and creeping things?”

“I,” Kit peeled the damp scrap of brocade from his breeches and tucked it into a sleeve, “am embarrassed to say.”

The stag tossed his horns. “And I am Geoffrey.”

“A pleasure to make your more formal acquaintance. Geoffrey.” Kit stood and stretched his shoulders. “Seeking me to what end?”

“Conversation. Were you bound for Queen Morgan’s cottage?”

“Yes.”

“And you found the way obscured. Unsurprising.” Geoffrey strode along the bridle path, and Kit fell into step beside him, crunching through leaves in the half-light.

“There’s a glamourie on it: you cannot find the way unless you know the way.”

“Ah.”

“Fret not,” Geoffrey continued, tilting his antlers. “I will show you.”

“Thank you. To what do I owe this kindness?”

“My desire for a moment to talk.” Long practice kept Kit from checking his step. “At last.”

“Surely a conversation could be had at less price”

“Tis no price at all.”

Strange and stranger, to see a man’s words fall from the lips of a hart.

“A token of friendship.”

“Friendship? Oh, aye. Follow me.” The stag left the path, leapt down a bank and pushed through a stand of laurel, Kit on his heels only stumbling once among the litter and sticks.

“Never step off the path,” Geoffrey said. “Never look back,” he glanced over his shoulder at Kit, long neck twisting like a ribbon “and never trust the guardian. A toss of his head back, westerly, toward the palace and the troll’s bridge.

“Unless you want to accomplish something. In which case you must risk, and intrigue, and sneak.”

“And betray?”

“Betrayals are a tricky thing in Faerie. You don’t wear Morgan’s mark of shame any longer. Does that mean you’re free?”

“The heartsease?” Half consciously, Kit brushed the breast of his jerkin with his left hand, feeling cool, supple leather. “Why should I be ashamed of it?”

Geoffrey stopped so suddenly that Kit almost slid into him. “Because of what it signifies.”

“Curse it to Hell and beyond!” Kit stepped back stubbornly, folding his arms. “Somebody is going to tell me what it signifies, or there is going to be blood.”

“Blood.” Geoffrey said the word tastingly. Of course. Mortal man. We re all fools.”

“Fools?”

“Has been so long since a true mortal walked among us. Tis changelings and half-Fae, and, well. It makes me wonder what the Mebd saw in advance of us, to steal a mortal away. Your obvious talents aside, no offense intended, etcetera.”

Kit, amused: “Of course.”

“And why Morgan would so lightly set you aside.”

He gestured Kit to follow with one expansive hoof. The beeches thinned, and yellow strands of grass began to thread between the leaves and roots.

“Why would a mortal man be important to the Fae?”

“We can’t fight a war without one,” Geoffrey answered, holding a branch aside. “A geas as old as the Fae. As for the heartsease. Its other name is love-in-idleness, did you know?”

“I’ve heard.” The branch was whippy and fine: Kit almost lost his grip on it after Geoffrey handed it across.

“Roses for passion and lilies for love and for death. Amaranth,” he smiled, “is undying love, eternity. And crocus is gladness, and pansy is thoughts but I do not think I’m so made mock of for a badge of thinking. So what, for the love of Hell, does a pansy signify?”

“Bondage,” Geoffrey answered without turning. “There’s your mistress house, poet. We will talk again.”

Kit turned to look through the gloom and the red twilight at a rose-twined cottage beyond a garden and a fieldstone wall. He turned back, to bid the stag thanks or something, but Geoffrey had vanished in a silence as utter as that of the dark wood behind him.

“Edakrusen o christos,” Kit muttered, because there was no Fae close enough to hear him. He placed one hand between the curling edges of lichen and vaulted the wall, rough stone gritting his palm and the turf denting under his feet.

A white gravel trail led him between beds of roses, red and white, and under an arch of blossoms damasked both. The beds below the roses were planted with mint, melissa, verbena, rosemary, lavender, and what seemed a thousand other sweet and savory herbs. The scent filled Kit’s head, almost dizzying, and he absently ran his hand across the bulge in his purse. The cottage was as earthed under with brambles as any in a fairy tale, and Kit smiled appreciation of the image. It didn’t look like the abode of a queen: the doorposts were skinned trunks, the door itself painted vermilionin a half-dozen coats that peeled as shaggy as the lichens. Lamplight gleamed through one small window, not yet shuttered against the night, and Kit’s breath ached in his breast as a shadow moved behind it.

I can feel her,he realized. Like a hand twisted in his collar, drawing him forward, and although his strides stayed as crisp as if he knew what he intended, he shivered. He glanced over his shoulder, wondering if the stag watched after, but the wood was dark and silent.

Bondage. His shoulder ached in a memory, blow of a silver dagger hard across its ridge, and he tasted an also-remembered trickle of lukewarm mint, and for a moment he wished he had, after all, brought his sword. Oh, he thought. Bondage. Yes, I see. More than her knight, her servant, her lover. More. Or less. Her slave.

“Hello the house!” Until the door swung open. “Good even, my lady.”

“Kit,” she said, gray-green eyes dark as moss in the twilight. Her hair lay unbound upon her shoulders, tumbling to her waist, its darkness shot with silver threads like a moonlit river. She wore only a low-cut smock with blackwork around the neckline and petticoat-bodies over it; a working woman’s home garb, her skirts kilted up to show a length of calf and a bare, clean foot, high-arched and more calloused than a lady’s foot ought be.

She tilted her head, and he looked down, studying her feet. His hand tightened on the nail in his purse; it parted the cloth and pricked his hand, but he didn’t let go.

[What brings you to my door, Sir Kit?” An arch smile, and her hand on his collar her physical hand, twisting the cloth and bringing him inside.

He moved as led, helpless under her touch, and thought of a stud horse rendered passive by the twist of a twitch on his lip. Kit opened his mouth, would have spoken accused her but the taste of bloody iron choked him. A vividly tactile memory of powerlessness: the savage wrench of his dislocated shoulder, gory drool slicking his chin and choking his throat with the effort of screaming and breathing through a mouth full of barbed metal, thinking If I could talk, I could explain my way out of this. There hadn’t been any talking. Not for a long time.

And it was still better than what Essex’s faction did to poor Thomas Kyd.

What greater cruelty to a playmaker than shatter his hand? Stop his tongue, show him his dignity and his sovereignty and his voice as easily rent from him as a girl’s Lavinia in Titus: raped, dismembered, silenced. She could have been a poet too, for all the benefit it got her.

Kit bit down on his tongue, knotted his fist on that nail, the pain shocking, before the memory went further. ah, but I lived.And there was satisfaction in that. “What have you,” like talking through a mouth full of blood. God help me. God have mercy…“What have you done to me?”

“Claimed you,” she said, and shut and latched the door, taking her time, giving him a moment to notice the airy interior of her cottage, the mud-chinked walls hung with tapestries and baubles and herbs. Roses grew through the gaps under the eaves to tangle across the loft where a high window gave them light: a perfumed, nodding mass of flowers. Her loom dominated the single room, her wide uncanopied bed against the far wall, a massive iron cauldron crouched upon the hearth.

“Iron,” he said, and let his bloody hand fall to his side, spattering a few drops on the rush-strewn slates rammed into the earthen floor. “Aye,” she said. “I’m afraid a little steel won’t protect you from Morgan le Fey. And I did no more to you than any lady might. I left you your freedom of speech and deed, which is more than the Mebd would have granted.”

She took up his bleeding hand and studied it; he hadn’t the strength to drag it away, and sagged against the wall beside the door, the stentorian echo of his own breath filling his ears.

“Freedom of deed? When I come to your bidding like a mannerly stud to the breeding paddock.”

“Have I interfered in your comings and goings?” She raised his fingers to her mouth and kissed the blood away. He turned his head as if he could burrow into the rough wool of the tapestry behind him. Her mouth claimed his fingertips. He moaned. She let his hand fall, then, and whispered, “Have I forbidden you London, for all tis foolery that takes you there? Have I forbidden you to amuse yourself as you wish, or made you pace at my heels like a cur?”

“Do I grant you dignity?”

“Arrogance and errantry, and how like a man not to understand what he’s given, and when his mistress is permissive, and how much more pleasant his station than it could be. At least a dog understands kindness.” He pressed his back against the wall, stomach-sick, eyes burning. Even when she stepped back, it was not distance enough.

“A cur, is it? Shall I bark at your door, madam? What dignity includes a slave’s collar and chains, a mark of shame?”

She turned away and moved toward her loom. He couldn’t watch her: it was a sort of agony to be in her presence, and searing pride alone kept him from prostrating himself before her. His fingers stung, still dripping blood.

The coolness of her voice cut through his fury. I see the first approach has come, then. “Who brought the flower to your attention?”

The wall was hard behind the tapestry. He blinked and straightened away fro mit. “Geoffrey the Stag. Wait, no. Puck and Cairbre, and the lamia Amaranth.”

“Excellent.” A rustle as she moved. He wished the taste of blood in his mouth were real; he wanted to spit.

“Look at me.”

He looked.

She stood as proud as a lioness, her long neck a predatory arch under her hair. He could have wept with his need to bury his face in it, but he thought she would have smiled to see his tears.

“You re mine,” she said, coming closer. “Don’t fight me, Kit: I’ve outlived kings and outwitted princes, and bent the noblest of knights to my will. In the end, they all did as I bid, or they died: I was a goddess before I became as you see me now.” Although her fingers cool on his throat, “Even Lancelot never fought me as you do.”

“Lancelot?” A froggy croak, clogged as the troll’s.

“You re worth three of him,” she answered with a storied smile. “Except on the battlefield. Where he was unstoppable. But that’s the sort of swordsman I need least in this new world.”

“Why me?”

“Because the Mebd wanted you, and I could get you for her. And get you from her.” He tried to speak, coughed instead. She stepped back, blessedly, and he battled the words until they came.

“Geoffrey said the Faerie host cannot fight without a mortal man.”

“Tis true. We have no reality apart from thy folk. And thy folk have no magic apart from us.”

“And that’s what you need me for?”

“Yes. That and the pleasure of your company.” A wink turned his stomach and tightened his groin. “You re angry with me. You think what I’ve done to you is a sort of rape.”

“Isn’t it?”

“Rather,” she answered. “But, then, so little of a woman’s lot is what she wills, I cannot see it as much different from a husband’s treatment of a wife. That is not a responsibility I will bear, strictly by merit of my sex.”

The spikes that had worn at his tongue and palate had been barely knobs, really. They had wanted him able to talk, afterward: the sort of bridle used for unruly wives, and not the sort reserved for heretics and blasphemers. Which had been meant to be a humiliation, too.

“No, I don’t think you can be blamed for how men treat their wives and daughters. But.” A pause as she laid a hand on his shoulder. “You might consider how much greater a dignity I grant you than my lord granted me. You, my sweet Christofer, have always your lady’s leave to speak your mind. How many women have so much privilege?”

“You’ll assess me the acts of a man a thousand years dust?”

“If I bear Eve’s sins, you may as well have Lot’s. No matter. You’ll do as I bid, though I’d rather you do it willing.”

Willing.Cold terror, suddenly. Worse because he knew that when she touched him, if he whimpered it would not be with disgust, or fear, as long as her hands were on him. Her movements were like a dance: nearer, further. An increase and a decrease of pressure. Laughing behind the deadly earnest of her gaze.

“If you fight me, Kit, I’ll break you. I’ve seen your scars. I have some idea of what it would take.”

His gut ached at the memory of her touch, the vagueness and blind lust with which she had afflicted his thoughts. He fought his voice level.

“And if I offer you my service willing in your coming battle, does that earn me your favor enough to beg the answer to a question?”

A shake of her skirts unkilted them; her petticoat fell to brush the floor. She sighed. “You may always question me. I consider it a fair payment for your inability to refuse. And I prefer a spirited mount to a brokenhearted nag.”

“What if I wish…” He couldn’t bring himself to say it.

She knew. “The sovereignty of thy person? Tis more than a wife gets, but I have the bond I need of thee.” She winked. “Although I might miss awell-warmed bed now and again. I can drag that magic off thee.” She snapped her fingers. He felt as if something a snapping branch, cracking ice broke to make the sound.

“Lady.” He relaxed as much as he dared, feeling suddenly light. He straightened away from the wall. “Tell me of Bard’s cloaks.”

“Bard’s cloaks? The cloaks of bards? What of them?”

“Is there virtue in them?”

“Aye, yes,” she said. “The magic of goodwill, a protection woven of the pleasure they have given those they give pleasure to. Has someone offered to start you one?”

A troll,” he said, and shrugged when she glowered at him. “One more question an it please you?”

“Aye?” She shook her skirts again, unhappy with how they had settled, ducking her black head so the rivers of her hair washed over her. Kit watched her move, and breathed a sigh to see only a lovely, dark woman, somewhat older than himself.

“Who do we intend to do battle with?”

She looked up and smiled. “Elizabeth’s enemies are mine own. Although we fight them differently. The Prometheus Club.”

“Oh, bloody Hell. Morgan, you should have just said so.”

Would they make peace? terrible hell make war

Upon their spotted souls for this offence!

WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE, The life and Death of Richard II

7th June anno Domini fifteen hundred & ninety five, Winding lane London.

My beloved friend In the fervent hope & intention that this small note may pass to thee directly I will speak plain, for I feel what I must impart is of too much moment to conceal under circumlocutions. We shall have to trust the privy ink in which these lines are written, between the stanzas of my latest manuscript. If I am too forward in thine estimation, then shalt thou burn this missive when thou hast read. I shall be as brief as I may: news in London is bad, & will unease thee. The Queen’s physician is finally dead, hanged at Tyburn last week. I was in attendance for thy FW, who miraculously still holds fast to life & breath although I know not how. A terrible thing, & I believe & FW & lord Burghley with me that it has much taken the heart from Her Majesty, for she was ever fond of Dr Lopez. In his last words, he swore his allegiance to HRM & to Christ, & died as thou mightst imagine, in exceeding pain. I will not say more; it is too close a memory for me of my mother’s cousins, who were hanged& drawn on suspicion of treason some years past. Thy letters tell me Poley watcheth me, & indeed I watch Poley, through the auspices of Poet Watson’s sister who is as good a woman as thou hast indicated & in much improved circumstance now, along with Robin her boy. Fret not, gentle Christofer: I am as cautious as ever thou couldst wish. But she, although Robert her husband will not see her, Robert’s friends will sometime pass her such nuggets & scrapings as they may says also that he & Dick Baines have been said to be much pleased by this torture & execution &they have made many midnight comings & goings. More, they receive succor in their treasonous efforts from overseas, a Spaniard she thinks & I think as well, keeps them supplied with coin. I have had this information to FW, but Oxford speaks well of Poley to the Queen, & so no action is taken. I suspect almost that Oxford has some secret hold on Her Majesty, for she is overkind to one who has not her best interests in heart. With what thou hast taught me I see how he doctors the plays that are meant to make Her Majesty strong, & his hand weakens every good line I put down, although I correct much of it more subtly than he knows. & still she loves him better than any but Burghley

Burghley, who is growing ill & aged, & his son takes more & more his place at the Queen’s right hand. Raleigh is out of favor again, & Essex has become openly hostile. He grows bold & conceals not his disdain for the Queen & the woman who loved him. It is his hand no doubt behind the conspiracy to convict & murder for I cannot call it a lawful execution Lopez, & his success & the Queen’s despair at it have made him drunk with power. & I have learned beyond a doubt that Poley is Essex’s man. Mary says Poley bragged in a tavern that he got money from Southampton. Which means Essex. Which means

I do not need to draw the obvious conclusions for thee, when Southampton, still in the guise of my patron & friend has asked for a play, a trifling thing. Thou wilt be unsurprised to learn that the topic of this play is Richard the second, & there is no way I can refuse without making it evident that I know more than I should. & that way lies a scuffle in a dark alley & a knife in the eye. More & more I feel I tread, forgive the casual blasphemy, like our lord Jesus Christ on tossing waves that might hurl me at my heavenly Father’s least whim to the snapping jaws of the deep. More, & worse. I told thee of gold from Spain: with that gold comes its bearer, a Spaniard or a Portuguese, not so dark as Lopez, hair almost auburn in the sun, as if he had some English, French, or Dutch blood. Perhaps a Jew as well? I did not hear his name, but he attended the execution with Baines, & was almost as tall, with a knife-blade nose & very thin lips behind a close-trimmed beard. Most strange of all, he wore rings on every finger, and from what I glimpsed of them I should say they were wrought of twisted iron. He is, I mean, Promethean. Mary has discovered his name: Xalbador de Parma, and heard as well in an unguarded moment one of Poley’s associates, a recusant named Catesby who I know, for he spends time at the Mermaid, call him Fray. & still worse & more interesting. Concealed in the crowd & my hood at the hanging, I made shift to follow those men back into the city. There is famine in London, Kit, & in the countryside as well. I saw the foreigner speak with Baines; he went into a tavern, & Baines like an errand-boy went off to do his bidding. What his bidding was I can guess, for there were vagabonds & chiefly apprentices rioting in London by noontide over the price of food, cheese & ale smeared on the streets, two suspected Jews & a Moor & some goodwives & tradesmen who might have looked too prosperous dragged through the street, pummeled or killed for the error of being abroad. Rumor has it culprits have been taken & are sure to be hanged at the Tower. Lads of 14, & I have no doubt that Baines who instigated shall not hang with them. I shall not attend. Lopez’s torture was all I could stomach, & I feel no need to watch the ravens feast. The riots mean the closing of the playhouses, & the Privy Council influenced by the Puritans who thou thinkst & I think influenced by the Enemy have ordered them torn down, although it has not happened yet. In some disgust, I contemplate spending the summer with Annie in Stratford, away from the stink & the plague that stalks London again. The drought is no better there, though, & the cattle sick with murrain. Bad omens, & the auguries poor as the Queen approaches her three score & three. It is almost as if the hand of God himself is bent against us, but I know it must only be such changes & expectations in the minds of men as thee & me, ourselves, do wreak with our plain poesy. At least lord Hunsdon is well, &he & the lord Chamberlain’s Men, we his players, remain in good odor with Gloriana. So I can shield her a little, & perhaps set a word or two against Essex’s murmurings & seditions, for plays go on at court even as the playhouses are shuttered. FW informs me that our next act must be to forge evidence against Baines and Poley, if we cannot come by it honestly and says to comfort me that there is no honor in it, but that we do it for the Queen. I know through FW what Essex does not: for all her refusal to name an heir, the Queen favors James of Scotland & she does court him with secret letters, privily instructing him in her arts of governance. Of course this cannot be made public, as Her Majesty’s position grows precarious & her wiles are not ah, thou hast me penning sedition again, what they once were. I fear some attack from our enemies. Something for which this abominable mess with poor Lopez is only the overture. Lest I trouble thee unrelievedly, let me say in closing that I am well, & writing strongly, as thou mayst see, & Anne has written to inform me that she will be buying me the biggest house in Warwickshire before I know I am agentleman. yr Wm Post script: I will set this by the mirror with a candle, as thou hast instructed, & write again when I have spoken with FW or Burghley. Post post script: please forgive the awkwardness of my hand. I hope that thou canst unriddle it, as I am prone of late to monk’s cramp, whose painful acquaintance I am sure thou, as a poet, hast made.

The tremors still subsided when Will put his fingers to a task. Such as flipping a silver shilling older than Annie. Mayhap as old as John Shakespeare: turning it in his fingers, over and over again, Will could just see the shadow of a hawk-nosed face when the light fell against it right. The shadow of Henry the Eighth, father of Elizabeth, founder of the English Protestant Church. And author of all my troubles,Will thought, laying the coin on the table beside the inkwell. He spread his pages across the desk and recut a quill, nicking his finger on the knife when his right hand trembled. He thrust the knife into the tabletop and his left middle finger between his lips. Damn it to Hell.

“Now there’s a scene from Faustus,” an amused voice said from the corner. “Writing our plays in blood now, are we? That should be some sorcery.”

Will pulled his bloody finger from his mouth and raised his eyes to the mirror. Kit lounged beside the fireplace, one elbow on the mantel, his left hand steering the hilt of a rapier.

“You could have announced yourself.”

“I was waiting for you to set down the knife,” Kit said dryly. He straightened and came forward, producing a kerchief from his sleeve. “So you wouldn’t cut yourself. Let me see.”

Will held out his left hand, picking up his pen with the right one to conceal its tremors. “Tis just a scratch.”

“Not so deep as a well, nor so wide as a church door? But deep enough, Will. Ah, you’ve missed the tendons and the bone. Good. It shouldn’t bleed longer than half an hour. Morgan would say to wash it with soap.”

“Lye soap?”

“Aye, and it might be wise. She saved my face from taint that way. Is there water in the ewer?”

“Some.” Bemused, Will suffered himself to be led to his bedroom and fussed over. He gasped when Kit scrubbed the wound, then pressed the edges of the cut tight and bound his first and middle fingers together with the kerchief to hold them closed and sop the oozing blood.

“Who is Morgan?”

Deftly, Kit tightened the bulky bandage. He gave Will’s hand a squeeze andlet it go. “My mistress in Faerie. A sorceress. That will bleed less if you hold it up.”

“Morgan?”

“Yes.” The sidelong glance. Kit’s face was pale, and Will thought if he touched his friend’s cheek it would be cool. “That Morgana. Will, about your letter.”

The bandage pressed the pain back to a dull, warning throb. Will gestured widely with his bloodied hand, and went in search of a rag. “I’ve wine hock. Can you stay a little?”

“I’d meant to. Are you expecting company?”

The stress on that word brought Will to alertness. He led Kit back into the sitting room. “Company? Burbage, you mean? Or Mary Poley ?”

“If they come, I can step through the looking glass. Give me that rag. I’ll mop the blood. You pour the hock. Tell me what Mary says of Fray Xalbador de Parma.”

That stress again, and Will puzzled it as he poured left-handed, despite his bandages. He got the harsh Rhennish white strained into the cups without spilling it and found bread and an end of cheese, which he set on the table beside the upright knife. “I’ve sugar for the wine.”

“I’ve gotten out of the habit,” Kit answered, tasting. “And this is sweet enough without assistance.”

“You know the name of the Spaniard.”

“We were acquainted. He pretends to many things but I had asked about Mary.” Kit twisted the knife free of the boards and cut cheese dyed with carrot juice, broke bread, handed the first bit to Will. “More on the Spaniard when the wine is drunk.”

“Everything she told me was in the letter. She’ll come again when she can.” The bread was hard to swallow. Will dipped it in his wine to soften it, much to Kit’s amusement.

“I see. And little Robin?”

“Sleeping better.” Kit rubbed bread between his fingertips. He rolled the crumbs against the tabletop. Will picked the shilling off the boards and turned it in his right hand. “Art jealous? Or is it that I’m jealous, and I pass it on to thee?”

“Jealous?” Kit looked up. He pushed the crust of bread away, and cupped both hands loosely around his wine, leaning back on his stool as if the scent of London, the reek of the gutters twining the perfume from the gardens pleased him.

“Of Mary Why should I be jealous?”

“Robin’s your son, isn’t he?”

Kit’s eye went wide, his face seeming to elongate as eyebrows rose and his jaw sank. “What gave you that idea?”

“Tis as good a reason as any for Poley to hate you. Beyond the political motives, which seem inadequate.”

“Adequate for murder. Inadequate for loathing.”

“I won’t think less of you… .”

“Nor should you,” Kit answered, reaching for his cup. “Given the somewhat hasty circumstances of your own marriage.”

Will laughed, knowing he’d touched a nerve to draw that response.

“Touch . Is he yours?”

“Why does it matter? I would not impugn the lady’s honor. A man can have care for a dead friend’s sister,”

“It matters,” Will said, “because a man can also have a care for the children of a dead friend.”

Kit balanced the knife across the palm of his hand. “Damn, Will. I don’t know.”

“What does that mean, you don’t know?”

Kit reversed the knife in his hand like a juggler; Will jumped as he drove the blade neatly into the same gouge Will had left earlier, and a full inch deeper.

“By Christ’s sore buggered arse, Will. It means the possibility does exist. I shouldn’t think I’d need to draw you a plan. Given yours come in litters.” The glare as Kit shoved himself to his feet left Will speechless and stung. He stood more slowly, holding out his bandaged hand, the right one tightened on the coin.

“Kit,” Will swallowed, a task that was growing uncomfortable. “I apologize.”

“Damn you.” But the edge dropped from Kit’s tone, and he settled onto his stool again, resting his forehead on the back of his hand. “Thy pardon, Will. I am overwrought.”

Will nodded, and sat as well, reaching out right-handed to grab Kit’s wrist, hoping his hand would not shake.

“The boy will want apprenticing soon. Had you a desire to see him in some trade or another?”

“God.” Kit’s voice was shaky. He clapped his left hand over Will’s right and squeezed. “Anything but a player, a moneylender, or an intelligencer.”

“Not to follow in his father’s footsteps, then? Whatever those footsteps be.”

The silence grew taut between them. Will drew his hand back and dropped it into his lap.

“Right. Cobblery it is.” When he finished laughing, Kit emptied his cup and pushed it aside.

“Xalbador de Parma. Fray Xalbador de Parma. A Promethean.”

“I had discerned that.”

“More than that.” His voice seemed to dry in his throat. Will pushed his own barely touched cup of hock across the table, and Kit took it with a grateful nod.

“A Mage, they call him, plural Magi. As if he had anything in common with great spirits such as Dee or Bruno. Fray Xalbador is also an Inquisitor, one of their infiltrators in the Catholic church.”