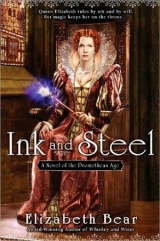

Текст книги "Ink and Steel"

Автор книги: Elizabeth Bear

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 23 (всего у книги 29 страниц)

Rejoice, ye sons of wickedness; mourn, unoffending one,

with hair in disorder over your pitiable neck.

CHRISTOPHER MARLOWE, On the Death of Sir Roger Manwood (translated from the Latin by Arthur F. Stocker)

Kit rolled over and lifted his head from the pillow as the bedroom door opened and Will slipped inside, half invisible in the starlit darkness. “You were gone a while,” he said softly, smiling when Will startled and jumped. I went to the library after all.

Will’s doublet was unbuttoned, his hair disheveled. Kit’s smile broadened. “Didst find what thou sought?”

“Nay.” Will started, pulling off his clothes. And then he stopped and moved toward the cupboard, a paler shape in the darkness. “Well, perhaps. After a fashion. So many books, Kit!”

“Faerie has some joys.” He turned away as Will struggled into a nightshirt. Plumage rustled as Will made himself a place in the featherbed, the perfume of a woman coming with him. Just as well,Kit sighed. Perhaps he’ll lie easier now that he’s reclaimed that.And then he caught the scent of rosemary and lemon balm on Will’s hair, and turned, mouth half open, before he stopped himself. I could wish he’d chosen differently or do you simply wish that you had chosen differently, Marley?

Will, half settled among the pillows, returned Kit’s stare wide-eyed. That as much as anything told Kit how fey his expression must be.

“Kit?”

“Will.” But what do you say? You haven’t a claim on him.“Thou hastn’t anything to prove to me.”

“Perhaps I had something to prove to myself.”

“Ah. Of course.” Kit opened his mouth again, to say whatever he had been about to say, and closed it before the words could escape. “Just be careful, Will.”

Will laughed, softly, and tugged the covers. “What chance have I against the likes of her, sweet Christofer, an she decides she wants me?”

For which Kit had no answer. The thrill of delight in Will’s voice told him more than the words, anyway. He lay back down, a serpent gnawing his bosom, and dreamed of sunlight and herb gardens and the beating wings of ravens and of swans. He woke again before Will did and stretched in the morning sunlight, surprised by how rested he felt. He stood and performed his toilet, stealing a glance at Will before he dressed. The other poet had burrowed so deeply beneath the covers that all Kit glimpsed of him was one ink-stained hand. Kit smiled fondly, for all he still felt seasick with jealousy, and went to collect his rapier from the stand beside the fireplace. I’ll have to get another main gauche,he thought, although he wasn’t sorry to have left the slender blade in de Parma’s back. I wonder what the coroner will make of a silver dagger, beyond the estimate of price?

He turned to check his hair in the mirror over the mantel, tilting his head in curiosity as he noticed the papers stacked there. The roll of poetry didn’t surprise him. The letter addressed in Will’s cramped hand to Thomas Walsingham did, and Kit’s fingers almost brushed it before he tugged his hand back. It’s not as if he made any effort to hide it from me. I could always just ask. If I weren’t so out of the habit.He settled the rapier on his hip one last time, turning for the door. Which reminds me, I should write Tom myself and let him know I’ve queered the game with Baines and Poley.

So early, the palace was still as quiet as Kit had ever seen it in daylight. He wandered downstairs, idling, and made his way into the hall to see what there might be to break his fast upon, if anything had yet been laid. A few Fae clumped at trestles along each wall, sipping steaming mugs and carrying on quiet conversation. Kit was first surprised to see brownies among those present, but quickly nodded. The kitchen staff dines early everywhere. He was less pleased to see Morgan le Fey rise from the sole occupied chair at the high table and beckon him, but he went. She looked composed this morning, lovely, robed in some fine, unrestrained black fabric that clung to her body when she gestured. Kit swallowed sharpness and moved forward, ascending the steps.

“Your Highness,” he said, and bowed.

“What, so formal, Kit?” She reached out and took his hands, drawing him to her side. She did not sit, and neither did he, aware that they made a lovely picture in their sable finery, framed against the crimson hangings at the back of the dais. Her hair was dressed, today, into a high elegant coil, a single strand of tiny pearls wound through its blackness. Her changeable eyes were poison green over the cheekbones of a goddess, and she suddenly took his breath away. “Art unhappy?”

“What have you done to my William, Madam?”

A raven-black eyebrow arched. “Your William, is it? And yet I heard you said to Murchaud that he was for the ladies, and in the manner of one who knows for himself the truth of his words. No matter,” she said, shifting abruptly, turning away from the hall without releasing his hand. She led him between the draperies, to a passage he had suspected but never walked down. “Come, spend a little time with me.”

“You are my mistress,” he said, and fell into step.

“Am I?” Her voice was hushed; if he didn’t look at her he could imagine they walked hand in hand like old friends, like brother and sister. When he turned to catch her words more clearly as he half suspected she intended, with the soft risings and dips in her tone, a barbed spiral he recognized as lust and jealousy and covetousness and the bitter dregs of a hundred other mortal sins, caught under his breastbone, and he drew each breath in pain.

Why should she have what I want so badly?

A bitter thought. An unkind thought. And unfair to Will, who was kindness personified.

“Are you my mistress? I come to your whistle.”

“Still you have not forgiven me?”

They came from the cloth-draped passageway into the throne room, and Morgan led him down from the dais with its chair of estate and the massive cloth-draped throne that Kit had never seen, nor seen the Mebd sit in.

“How can I forgive…” He caught the words in his teeth before they quite got away from him. She held his arm, leaning close enough that he could smell not only her own pungency of rosemary and rue, but the traces of another’s scent on her hair and clothes. He breathed in through his mouth, and told himself it was against the pain in his bosom.

“That is to say, Madam, whatever your sins, they must be outweighed by your favors.”

She laughed. “My favors weigh so heavily on thee? If tis jealousy that drives thee, Sir Christofer, then my favors can be thine for the asking. It was not I who ended our arrangement.” He coughed and tugged away. She kept walking while he stood, her gown trailing like the train of a jet-black peacock, and turned back only when her hand touched the door.

“I wish my friend safe,” he said.

Her eyes glittered as she smiled and inclined her head. “You wish more than that.”

“Aye.” A groan. He turned away. “As if something buried, once watered, has sprung into the sun and flowered on a day, and now will not be withered no matter how I scorn and strike it.”

“I could give thee a spell to make him love thee.”

“He loves me well enough,” Kit answered, hating his own honesty. “And that I should be content with.”

Her skirts rustled across the tile as she drifted to him. Her hands encircled his waist, her chin resting on the padded shoulder of his doublet. “Could give thee a spell to do more.”

Kit bit his lip as her breath stroked his ear. Her breasts pressed his back, her fingers demonstrating what he was sure she already knew. She could. The experience that proved it was as painful as the experience that proved it was not just her magic that aroused him, although free of the sorcery he could almost pretend it was the touch alone, nothing more than a whore’s practiced hand. She could give me Will.

“Madam,” he whispered, “What do you take your Marley for?”

She laughed in his ear; he turned in her arms and laid his own around her shoulders, holding her away as much as close. “Anything he’ll offer me,” she said. And then, more kindly: “No, thou wouldst not be my Christofer if thou wert so base as thy Morgan in such matters.”

She smiled and would have stepped back, but his arms restrained her. She turned half a step; they moved as if dancing, her train winding their ankles, binding them together. She ran fingers up the breast of his doublet and touched his lip. He frowned, and she brushed the corner of his eye as if something gleamed there.

“Hard,” she said. “Hard it is to love something, to need something, and to have it taken from thee. There are simples to ease that pain as well.”

“That pain,” he said, “is sheerest poetry.”

“He would not like it if you bedded me today.”

“I do not like that he bedded you last night.”

“There was,” she smiled, her breath against his skin, “no bed.”

“Ah.” And indrawn breath. It cut.

“Come to my room, Christofer.”

He shook his head, but he didn’t step away. “I should go. Go to Murchaud, Morgan. I can smell him on your skin.”

“I know,” she said, brushing her lips across his lips. “I left it for you. Come upstairs.”

As if he had always known he would, he went. Morgan curled against Kit’s side, her sweat drying on his arm. She laid her head on his shoulder, the pearls half worked loose and falling across his throat. Blessedly, she held her peace until his pulse no longer rasped in his ears, and he opened his eye again and turned to look at her.

“Such passion, Kit.” She knotted a fistful of the linen sheet in her hand and dried her face; offered him the same. He rubbed the sweat from her body and untangled the pearls from her hair, laying the strand aside before pulling her down beside him again.

“That was different. Thou wert not ensorceled.” Silly man, her pursed lips said, and he had to agree.

What do I here? Is that all? Enough.

She drew the damp sheet over them, idly toying with his hair.

“Tell me whence comes this sudden affection of thine for poets.” He brushed her bare leg with the side of his foot. A tremendous hollowness still haunted him, something as consuming as a flame, but for now he could set it aside along with the images it taunted him with and draw the silence of his heart over himself as Morgan drew the sheet.

“Not sudden,” he admitted. “I knew it years ago.”

“Oh?” A quiet sound of interest, after a long and companionable wait. Damme, what an intelligencer she would have made.He sighed, and managed not to sound sullen. “Damn you, Corinna. Is’t not enough to have us both? Must also step between?”

She turned against his neck, tasting his skin with her smile.

“There are reasons I stopped going to London.”

“When knew you, then?”

Kit laughed. “He tripped climbing a stair and I almost swallowed my tongue in panic.”

Her fingers coiled his hair and pressed unerringly against the sore places in his neck. “Speaking of falling. You should have come to me after you did.”

His and Will’s ignominious tumble through the Darkling Glass, of course.

“How did you know I fell?”

“The bruises on your arse.”

Their laughter drew the tension out of his shoulders almost as effectively as her fingers; he rolled on his stomach and let her lean over him, working the pain from his back. “The teind is soon,” she said, stressing every other word as she leaned into him, an oddly artificial pattern of iambs. “The sacrifice will have to be chosen.”

“Ow.”

“When you tense, it hurts.” Warmed oil drizzled onto his back; he didn’t ask where it came from, as her hands never left his body.

“How is that done?”

“This?”

“The sacrifice chosen.” He groaned as she ran strong thumbs from the top of his spine to the base, and did not stop there. “Gently, my Queen.”

“Poor Kit. Black and blue from here to here.” Her fingers measured a span bigger than his palm. “Thou’rt lucky didst not break thy tail”.

“Art certain tis unbroken?” And realized he’d thee’d her, and thought, and would it not be an irony to you her so engaged?

“Evidence would suggest.” He gasped, burying his face against her herb-scented pillow, and she laughed.

“Wilt urge me proceed gently here as well, Sir Poet? Will you write me poems on this?” Her hair swept his shoulders; he shivered, jolted from his fantasy of whose touch he labored under.

“When will we know who is chosen?”

“When they bring the horse before the one who will ride him to Hell. There. Is that nice, my darling?” A kiss between his shoulder blades; another brushing the downy, well-oiled hollow at the small of his back. “Are you thinking of your poet now?”

He couldn’t bring himself to answer.

By my troth and maidenhead I would not be a queen.

WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE, King Henry VIII

The Queen’s withdrawing room, revealed through an opening door, wasn’t as grand as Will had expected; rather a quiet sunlit place appointed with rich paintings and more of the extravagant carpets, these in harvest-gold and winter-white, with touches of emerald and sapphire in the plumed weave. A small table stood in the center of it, a cushioned chair at either end, a service of silver-gilt and golden plates laid on linen as white as Morgan’s sheets.

He smiled at the memory and executed a sweeping bow, resisting the urge to reach into his pocket and fumble the scrap of iron nail Kit had pressed upon him before the appointment. The Mebd stood before the window, her hair gleaming under her veil; she turned to acknowledge him. “Gentle William. You brighten our court. Pray rise.”

“Your Highness is most gracious.”

They were seated, and attendants Will could not see poured wine and served them both. Nervousness robbed him of his appetite: his knife shivered on the richly decorated plate. The Queen herself ate delicately; he was surprised to see that what she cut so tidily and placed in her mouth was wine and capon, and not flower petals and dew.

“You hunger not, Master Shakespeare?”

“I am curious,” he admitted with whatever charm he could muster. And now I’ve met three Queens,he thought. And swallowed a broader grin as he also thought, and bedded one.

“Curious?”

“Curious what Your Highness would have of me.”

She smiled and laid her knife across the plate. “Perhaps you and Sir Christofer would consent to honor us with a play.

“A collaboration? We’ve done it before, Your Highness. I’m sure Kit would agree.”

“We have faith in your ability to convince him,” she said.

Will picked up his goblet as she contemplated her words. “We were favorably impressed with your Midsummer Night’s Dream. Although it saddened us to see your Queen in the end humiliated and defeated by her unsavory husband. It seems to us that she, Titania, had the right of it, and that is not merely our sympathy for a sister Queen.”

Will frowned, tasting the unfairness of his own life in the irony of his words. “It is the experience of this poet, Your Highness, that just women are often misruled by their husbands.”

“And just peoples misruled by their Princes, by extension?”

Too late, he saw the trap. He nodded. “And yet such is the way of the world: many a man abuses the trust of a woman who deserves better, and yet they and the world are so made that they must accept the dominion of men.”

“Many a Prince abuses the trust of his subjects, and yet how few men are born to rule?” She rolled her silver-handled knife between fingers white and soft as cambric. “And yet thou dost serve a woman who is also a Prince. Is she deserving of thy sacrifices?”

“Your Highness, aye.”

“Why is that?”

“Because…” He shrugged. “Because she has made her own sacrifices, to keep her people safe.”

“Ah.” The Mebd closed eyes that had shifted from green to lavender and then to gray. When she blinked them open, they were the color of thistles under gold lashes worthy of a Hero. “So the sacrifices a husband makes for his wife earn her loyalty. If he is worthy of her.”

He lowered his eyes, unable to support her inquiry, and dissected a morsel upon his plate, sopping the meat in sweet-spiced gravy. The flavor cloyed.

“And are you worthy of your wife, Master Shakespeare?”

“No,” he answered, without looking up. “Madam, I am not.”

“And yet she serves you as you serve your Prince.”

“Aye.”

“This is what we adore our poets for.” He was surprised by the tenderness in her voice into glancing up again. “They lie with such honesty.”

“Lie, Your Highness?”

“Aye.” A smile on her lips like petals. “Sweet William is a flower. Didst know it?”

“Aye, Your Highness.”

“Perhaps we shall have some sown.”

Will nodded, dizzied. Emboldened, a little, by the frankness of her conversation, he asked a question. “Your Highness. Like Gloriana, you have no King.”

“I will be subject to no man,” she answered. “Even a God.”

“And yet from what Morgan tells me, Faerie is subject to Hell and its lord.”

“Women,” she answered, extending her white-clad wrist to pour him wine with her own pale, delicate hands, “have long learned to simper in the presence of their conquerors. And not only women, Master Poet.”

“No,” he answered, tipping his goblet to her in salute before he drank. “Not women alone.”

“We are glad,” the Mebd said, “you have agreed to dine with us today. We trust you will never find yourself bound in an unpleasant subjugation.”

“Your Highness.”

“Yes.” She smiled as she touched his sleeve. “I am.”

Had I as many souls, as there be Stars,

I’d give them all for Mephostophilis.

CHRISTOPHER MARLOWE, Faustus

Kit unhooked his cloak and threw it over the high back of his chair. He leaned on Murchaud’s velveted sleeve and watched the dancers eddy across the rose-and-green marble tiles, wondering if he could afford another glass of wine. The way Will’s head bent smiling as he whispered in Morgan’s ear was making him want one, badly, but he suspected that it would be unwise to indulge.

“It looks as if thou mightst have room in thy bed tonight,” Murchaud said conversationally, drawing his arm from under Kit’s head and dropping it around his shoulders.

“Aye. I’ll sleep alone tonight.” And in the morning, Morgan will find me. Sweet buggered Jesus, how have I come to this?

“If thou wouldst wish companionship…”

“Perhaps,” Kit said, and poured water into his glass. He sat upright to drink it, as Murchaud played idly with the strands of his hair. “Aye. Dice and wine, perhaps a pipe? To begin with.”

“Thou canst defeat me at tables again.” Kit chuckled. Murchaud’s luck with dice was abysmal enough to be notorious. “For a start.”

Murchaud reached past him for a tart and leaned forward to eat it over the table, scattering crumbs. “Hast spoken more with Geoffrey?”

“Words in passing.” Kit drew up a knee and laced his fingers before it.

“Wilt give him thine answer?”

It wasn’t really a question, Kit knew. “Shall I offer to betray you, then?”

“That would be kind.” Murchaud leaned back beside him, crossing long legs, his right foot flipping in time with Cairbre’s fiddling. The song wound down;the dancers paused.

“We need to know the nature of the plotting.”

“Ah. Yes.” Kit stood and glanced over his shoulder at Murchaud, sweeping his gaudy cloak around his shoulders as he did. “Thy mother seems to have abandoned my poet,” he said. “I’m off to comfort him. And yes.”

“Yes?”

Kit turned away. “By all means, come and see me tonight.”

The stairs were less trouble sober, although he cursed the lack of a railing under his breath. He skirted the applauding dancers on the side away from the musicians, not wishing to capture Cairbre’s eye and be summoned to perform. Will must have seen him across the floor, because he met Kit halfway. Kit ached to look at him, giddy with dancing, color high and eyes sparkling like the gold ring in his ear in the light of the thousands of candles and torches.

They love him because they cannot keep him,he reminded himself, and forced himself to smile. “Will. Come have a drink with me.”

“No dancing for you, Kit?”

“I don’t pavane,” Kit said dryly. “Neither do I galliard. Stuffy dances for stuffy dancers. Come, there’s spiced ale by the fire.”

He led Will to the corner by the tables and filled cups with the steaming drink, redolent of cloves and sandalwood. They leaned between windows, shoulder to shoulder, and Kit buried his nose in his tankard, breathing deep.

“The Queen wants us collaborating,” Will said, swirling his ale to cool it. “A play by Hallowmas, it seems.”

“A play?” Kit turned to regard Will with his good eye. “Did she assign a topic?”

“Not even a suggestion. Please, overwhelm me with your brilliance.”

“The Passion of Christ,” Kit answered promptly, and was rewarded by a gurgle as Will clapped a hand over his face to keep his mouthful of ale from spraying across the dance floor.

Choking, “Seriously.”

“Damme, Will. I don’t know. Thou hast had longer to think it than I have. They won’t care for English history.”

“I left my Holinshed in London, in any case.”

“Coincidentally, so did I. I wonder who has it now?”

“Tom,” Will answered. “Unless he burned it. He was very angry with you for some time.”

“Only fair. I was very angry with him.” Silence for a little. They drank, and Will took the cups to refill them. When he returned, he rolled his shoulders and kicked one heel against the stones.

“Why the Passion?”

“Suitably medieval,” Kit replied. “Like so much of our religion.”

“Still no faith in God, my Christofer?”

“Faith, William?” Kit tasted the ale; this cup was stronger. “Died blaspheming, indeed. Do you suppose He eavesdrops on those who call His name in passion? Oh, God! Oh, God! Mayhap He finds it titillating.”

“Kit!”

Kit snorted into his cup. “Faith. I faith, the Fae, who ought to know it, say God is in the pay of the Prometheans. I imagine He’d little want me in any case.” No, and never did. No matter how badly I wanted him. A little like Will in that regard, come to think of it.

“I sometimes suspect,” Will said softly, “that God finds all this wrangling over His name and His word and His son somewhat tiresome. But I am constrained to believe in Hell.”

“Hell? Aye, hard not to when we’re living in an argument on metaphysics.” Kit kicked the wall with his heel for emphasis. “Say that again once the Devil’s complimented you to your face.”

“But I am the Queen’s man, and the Queen’s church suits me as well as any, and I should not like, I think, to live in a world without God.”

“An admirable solution,” Kit said. “I flattered myself for a little that God did care for me, but I felt a small martyrdom in His name was enough, and He has never been one to settle for half a loaf. And I am maudlin, and talking too much.”

“I do not think your martyrdom little.”

“Sadly, it is not our opinion that matters.” Kit had finished the ale, he realized, and felt light-headed. He set his cup on the window ledge and leaned against the wall, letting the cool breeze through the open panes stir his hair. He put a smile into his voice.

“Your celebrity here is not little, either.”

Will laughed, and leaned against Kit’s shoulder. “I find the affection in which I am held adequate.”

“For most purposes?”

“The purposes that suit me. Are all poets admired in Faerie?”

“Only the good ones,” Kit answered. “And yet I envy you your freedom to go home.”

“If I knew a way to bargain for yours…”

“Poley would simply have me killed again.”

“He might find it harder this time.”

“Ah, Will. Everyone in London who loved me is gone. What had I to return to, even were it so?” Kit shook himself, annoyed at his own sorrow, and knowing as he said it, “Will, forgive me. Those words were untrue, and unfair.”

“I understand, Will answered. As for me, I am half ready to flee London overall. Our epics are not in fashion any longer, Kit. Shallow masques and shallower satires, performances good for nothing but jibing. More backstabbing and slyness than old Robin Greene ever dreamed of. Stuff and nonsense, plague and death. Stabbings in alleyways, and I’m as much to blame as any man, because my plays do not catch at conscience as they once did. My power is failing with the turning of the century.”

“Failing?” Kit laid a hand on Will’s shoulder and shook him, not hard but enough to slosh the ale in his cup. “Foolishness. The power is there as always; in every line thou dost write. It’s merely…” Kit squeezed, and shrugged, and let his hand fall in abeyance. “Because it depends, in some measure, on the strength of the crown.”

“Another raven.” Will set his cup aside and pushed away from the wall. “Waiting for Gloriana to die.”

Kit plucked the figured silk taffeta of Will’s sleeve between his fingers, drawing his hand back before the urge to stroke Will’s arm overwhelmed him. Across the hall, he saw Morgan mounting the steps to take a seat at the virginals. At least our feathers glisten.

“Look, Will. Smile, go dance attendance. Your lady takes the stage.”

Will looked him over carefully, boots to eyepatch, a frown crinkling the corners of his eyes. Kit held his breath as the poet leaned so close that Kit almost thought his lips might brush Kit’s cheek. But his hand fell heavily on Kit’s shoulder, and his frown became a smile. “I’ll see you.” Kit turned and took himself upstairs, to wait for Murchaud and the backgammon board.