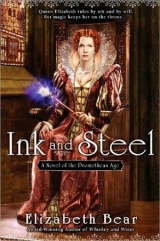

Текст книги "Ink and Steel"

Автор книги: Elizabeth Bear

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 21 (всего у книги 29 страниц)

Mercutio:

Without his roe, like a dried herring: O flesh, flesh,

how art thou fishified! Now is he for the numbers

that Petrarch flowed in: Laura to his lady was but a

kitchen-wench; marry, she had a better love to

be-rhyme her; Dido a dowdy; Cleopatra a gipsy;

Helen and Hero hildings and harlots; This be a gray

eye or so, but not to the purpose.

WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE, Romeo and Juliet

Will knew something had happened, that Kit’s rendition of “Greensleeves” had somehow been a challenge, the smack of a gauntlet against an unprepared face. Knew it more when the music that resumed after Kit left the small stage was wordless, and Morgan excused herself, smiling, and went to climb the dais beside the Queen and the Prince. Who shortly thereafter removed themselves from the hall. Will, rested from the afternoon’s nap, mingled joyously with musicians and poets, with the Faerie players that Kit had recruited for his masques and plays, until at last Kit found him and tugged his sleeve toward the stair.

“It looks desperate to be the last one at the party,” Kit said. “Unless you were planning on leaving with the brunette.”

Will glanced back at her. She smiled coquettishly behind a fan of painted mauve silk, and he waved and turned away. “The fangs are a bit disconcerting.”

“She’s Leannan Sidhe. You’d never be the same.” Kit lit a candle at the base of the spiral stair, and Will climbed in silence beside him.

“Leannan Sidhe?” He tried to mimic Kit’s pronunciation.

Kit hesitated, his hand still warm on Will’s arm as they made their way upthe stairs. “Blood drinkers. A man can’t be too careful, in Faerie.” Will watched Kit open the door. “Black Annie,” he said. “Only men, not children. She’s got a special affection for poets.”

Kit ushered Will inside, latched the door, and found cups and a bottle in the cupboard, upon which he left the candle. “Tis said her love gives inspiration.”

“And have you availed yourself of this inspiration?”

Will took the cup Kit offered him and held it under his nose. The scent made his eyes tear. “Brandywine?”

“Better. Tis called uisge. Be careful.”

As Will sipped, and coughed, and Kit laughed at him. “No, dying young once was enough. But I wanted to talk to you about your play.”

The fire of the liquor sliding down Will’s throat did nothing to calm the tension in his shoulders. He told himself, any ripples shivering across the tawny fluid in his cup were just the effects of his palsy, and set it down before he could spill it. “You disliked it.”

“I could not adore it more,” Kit said, refilling his cup. He leaned against the great carved post of the bed, curtains rumpling against his cloak. As if irritated, he unfastened the clasp and leaned forward enough to free himself of the tattered finery, tossing it to the bed. The single candle cast gentle shadows across his face; he drank and continued talking into Will’s silence.

“You’ve cast me again, haven’t you? As you like your Rosalind. Your Ganymede.” Will laughed. “You caught me out. The first to notice it enough to warrant a mention.”

“How could they miss? Ganymede, Leander, dead shepherds. A crack about a great reckoning in a little room and another about incompetent historians? You should not take such risks.”

“Not a risk if no one notices.” Kit laughed, staring down into his cup. “Kit in skirts, I should be offended, I suppose, but she’s a delightful girl. Although to call her Ganymede were an ungentle jest”

“Ungentle? I thought to reference your Dido… ”. And not painted boys un trussing in doorways? I suppose that’s all right.”

“I beg your pardon,” Will picked up his cup and gulped more liquor, liking the second swallow better. “I intended no offense.”

“Naive, Will.” Kit dismissed it with a tilt of his hand. “She’s a marvelous character. Any man with the wit to choose a resolute wench would die for such a maid.” And then hastily, as if afeared: “Is that how thou seest me, Will?”

“How I … Damn.” How does he always manage to weasel me into the honesty I don’t want to give?The liquor gave Will courage, and he wondered if Kit had intended it so. “Perhaps how I would see thee, if I could.”

That beautiful, ruined face turned toward him, and Kit set down his cup on a relief-carved trunk and closed the distance a few hesitant steps. His forehead shone pale, candlelight burnishing a thin gloss of sweat. Will swallowed.

Kit’s careful, measured voice coiled his limbs like the tendrils of a fog, cat-amused. “And were I a woman, a maid, what wouldst will of me?”

Will grinned and stepped back, far enough that he could breathe again. The closer Kit came, the vaster grew the tightness in Will’s throat. He tossed back what was in his glass; it seemed easier to swallow, and a pleasant looseness imbued his muscles.

“Wouldst measure thy will gainst mine? I’d say a maid at thine age hadn’t been striving for another state.”

“I’d be inclined to agree. Dost wish more drink?”

“Wine, an thou hast it.” His throat was dry; wine would comfort it.

“By all means, put me to use.” Kit busied himself at the sideboard; Will watched how his curls snagged and slid on the velvet across his shoulders. He would have made a lovely girl. To use? Pouring and fetching?

Kit checked as if Will had flicked his nose for overcuriosity. “Pity mine impertinence. Tis queer to see oneself given a woman’s body. And, in my situation, a rare pleasure to be remembered.”

Bitterness on that last word, and Will flinched from it as Kit returned his cup.

Will drank, and Kit drank too. The silence lasted until they’d drained the wine. Will set his cup on the window ledge with a soft click and twisted his heavy new earring in his ear before he spoke. The words that came were not the words he’d intended.

“Kit, why would any man permit …” He swallowed, stuffed his traitor right hand into the pocket of the borrowed sunflower doublet. “Isn’t it agonizing?”

Kit cleared his throat, looking away, dispossessing himself of his cup as well. “Rather thou shouldst say, exquisite.”

“I find it difficult to comprehend.”

“I,” Kit paused, still looking down, face suddenly pale around a flush that marked consumptive circles on his cheeks, bright enough to show by candlelight, “could show thee.”

“Ah.” Will’s mouth that had been so dry was full of juice now. He swallowed it.

“Thou…”

Kit was trembling. Like a leaf, like a girl, like a rose petal twisting in the breeze, about to be lifted from the stem.

“Do not I possess mine own body, to pray God as I wish, to speak as I wish, to love with as I wish?”

Which was heresy again, and sedition, and half a dozen other things. To which Will had no answer.

Kit smelled of sweet wine and herbs, and that fiery taint of uisge. Soft boots silent on red-and-gold carpet, in one endless moment, he came the few short steps to Will diffidently, like a man wooing a maid. Gaze on gaze, as if watching for the instant when Will might startle, he raised spread fingers and slid them up Will’s cheeks, brushed his ears, combed his curls with them. Then took Will’s face tenderly between his hands and, tugging him down, nibbled Will’s lips until they parted. “William, my love.” A kiss at first as hesitant as a maiden’s, but then deepening as Will softened into it; and yet unlike kissing a maid, for all Kit’s lush mouth and pouting lip, because that mouth and tongue were knowing. There was the aggression of it, the light control exerted by Kit’s hands in his hair, the yielding lips fronting a seeking tongue, the brush of beard against beard, the hardness of a man’s muscled body in his arms. Literally in his arms; Will blinked to realize he’d pulled Kit close, dust-colored curls between his fingers, leaning into the forbidden, erotic kiss that drained blood from a suddenly light head to warm and throb in his loins.

A swarm of moths beat hungry wings toward the candle flaring in his breast, he jerked free. A string of saliva stretched between their mouths, glistening. “Pity,” Kit said, and broke it with a fingertip, stepping away. “More wine before we sleep?”

“No,” Will said. “I think I’ve had too much already. Art ready, for sleep?”

“Aye,” Kit answered, unbuttoning his doublet’s collar. “To sleep.”

“Will lay in darkness, listening to Kit’s slow breathing, hugging his nightshirt close to his sides. How can he sleep like that, as if nothing transpired? Sleep is what you should be doing as well,he reminded himself, and closed his eyes resolutely on the faintly moonlit swells and valleys of the canopy overhead.

Will nibbled his thumbnail, stopped quickly at the subtle reminder of the pressure of lips on lips. He turned on his side, careful not to shift the coverlet, and buried his face in a tightly clutched pillow as if the greater darkness could silence the voice in his heart.

What if I had shown him those poems? He knows. He must know. Or was he just being Kit? He shocked all Faerie with that song of old Harry’s. Did he want to shock me too? Did I want him to know?

Kit never stirred. Will cursed him his complacency, the even rhythm of his breath, the relaxation in his shoulders under the whiteness of his nightshirt when Will turned to look at him in the moonlight. Wondered what would happen if he, Will, put out his right hand and took Kit by the shoulder and turned him to the center of the bed, and stole another kiss. It would be more than a kiss now, and that, thou knowest.He sighed, and rolled back to his own side of the bed. O let my books be then the eloquence, And dumb presagers of my speaking breast. And what if I told him that? Would he kiss me like that again? What else would he do? Would I want him to?

An unanswerable question, for all Will would have known the answer short hours before. The night passed in discomfort, until the last grayness before the first gold of morning, when Kit’s muttered whimpers and bedding-snarled struggles drew Will upright.

“Kit?” No answer, but a low, tangled moan. Kit’s hand reached out, as if to grasp something, or ward it away, and Will impulsively caught his wrist with both hands. “Kit.”

Who blinked, and drew the hand back, self-consciously, rubbing at his scar. Who looked strange in the half-light, divested of the eyepatch.

Will still hadn’t quite accepted; Will wanted to reach out and touch that long whitescar, the drooping eyelid, the bland, pallid orb underneath. He tucked his hands below the covers.

“Dream,” Kit said softly, turning aside as if Will’s gaze discomfited him. “Damn me to Hell, Robert said they were supposed to get better after I made the cloak”

“What sort of a dream?” Will drew back among the pillows, propped against thebedpost. “Nightmares?”

“Robert said they were prophecy, and indeed I had one of you in Baines clutches. Twas what drove me to your rescue. But stitching that cloak was meant to bring their power under control. Prophetic dreams are all very handy, I’m sure, but if I cannot sleep at night, any night, I’ll be of no use to anyone.”

“You slept a little,” Will said.

“I had …” Kit stopped, his hands fretting the bedclothes. “Just drifted off a moment ago.”

“Oh.” Wariness, and then a cold sort of delight. Not so cool as he pretends, Master Shakespeare. It will not behoove you to be cruel.

“The cloak,” Will said; anything to break the fraught, gray silence. “What if you spread it over the bed? There’s herbs that keep dreams off if placed under your pillow. Perhaps it holds the same sort of virtue.”

Kit lifted his chin and slid his legs out of the bed. He’d pulled the cloak off its foot the night before and folded it neatly over the back of thechair; now he shook it open and laid it over the coverlet. The fabrics dark and bright, rich and plain, were hypnotic; Will reached out and stroked a rose-colored trapezoid of brocade. “Why a patchwork?”

“Kit smiled. Morgan and Cairbre say it signifies all the hearts a bard has pleased with his music; it represents protection, for the good will of all those listeners and lovers interlinks to a garment that keeps ill magic and ill fate away like ill weather. A very old kind of sympathy.”

“So not a fool’s motley, then?”

“They both represent something sacrosanct.” Kit clambered back into bed, making a show of pushing his pillow around, and lay down with his back to Will again. “A tatterdemalion sort of magic, but there you are.”

“Which patch is from your Prince?”

“He hasn’t given one.” A hesitation. “The green-figured velvet embroidered with the unicorn, though. That was from Morgan, and oddly formal for a thing that’s meant to be made of scraps and ragged leavings.”

“As if the Bard, in exchanging pleasure and truth with many, isn’t entitled to a single whole life of his own.”

“Rest easy, Kit,” Will said, because he could not think what else to say. “I’ll wake you again, if need be.”

For such outrageous passions cloy my soul,

As with the wings of rancor and disdain,

Full often am I soaring up to heaven,

To plaint me to the gods against them both:

CHRISTOPHER MARLOWE, Edward II

Kit awakened for the second time almost rested, and he wasn’t entirely certain whether it was the mingled silken and harsh fabrics of the cloak bunched in his fists that made the difference, or Will’s arm around his shoulders, bridging the careful four inches that separated their bodies. The rhythm of Will’s breathing told him the other poet was not sleeping. “Was I dreaming again?”

“Complexly, I gather, from thy conversations.” Will drew back as Kit turned to face him, and Kit frowned.

Aye, Marley. And your own damned fault it is. What wert thou thinking? More to the point, what wert thou thinking with?

“Conversations? What did I say?” Kit sat upright, reaching for his eyepatch.

At least I didn’t wake up screaming this time; the cloak must have its uses.Will blushed, and as Kit asked, he remembered a flurry of wild white wings like Icarus, doves? Swans? If it’s swans, does it mean Elizabeth? There seems to be a symbolism running through these dreams of mine, rather than a literal thread. And there had been blood, and pentagrams.

“Thou didst call on Christ to save thee. Begged someone to finish something, or make it done. And then Consummatum est.”

Kit stood and pulled his nightshirt over his head, stumbling across the carpet to the wash-basin. He all but felt Will avert his eyes. “I remember now. If I could only remember what it is that was done…”.

“Yes. Kit.”

Kit turned back, preserving some semblance of modesty with the nightshirt in his hand, amused at Will’s reaction to his nudity. Unkind, Christofer. I am what I am.

“What is that mark on thy side? Oh, there’s another.”

“Five,” Kit answered, remembering how they had burned as if writ anew on his flesh, in the dream. “One on my breast. One to each side, just below the ribs on my belly. One gracing each thigh, like the points of a star.”

“The circle of Solomon or the pentangle?”

“I imagine the circle would have required more men. And then, circles are for keeping something out; pentagrams for keeping something in. Stopping my voice in my throat, like the bridle. And when my Edward proved to them they had failed to break me, they killed me. God in heaven, I hope I never know what Oxford was thinking when we Lacrima Christi. When we were together.”

“How much did he know? ALL of it?”

“Not an accident, then. Rheims,” Kit said, and waited. “Did you think I was kidding about the irons, Will?”

When Will said nothing more, he turned away again and went to wash himself in the icy water before finding a clean shirt and leaving the basin to Will.

“Tis nigh on afternoon. Not surprising; we scarcely slept till morning. Have you plans for the evening?”

“Will we be expected at dinner?”

“Dinner is cold shoulder. The court prefers to gather for supper, and for sport and entertainments after. Thou’rt still nine days wonder enough that thou shouldst appear. I certainly will.”

Kit’s clothing seemed to have expanded overnight, some brighter colors among the blacks and greens Morgan favored on him: clothes narrower in the shoulder and longer in the arm.

“Your wardrobe has arrived.”

“Does it involve a clean shirt?

Aye, a selection.” Kit stepped aside so Will could pick through the pile.

“Wilt explore Faerie?”

“Is it safe?”

“No.” Kit said. “But I’m only writing a play on Orfeo gone to Faerie now, or perhaps tis Orpheus gone to Hell. I could accompany you.”

“If it’s not an inconvenience. Is there a difference, between Faerie and Hell?”

“When I’ve seen Hell, I’ll tell thee.” A light knock interrupted. “A moment!” Kit caught his cloak up from the bed and hesitated.

“Will, is this thine?” Something gleamed in the middle of the coverlet, as if it had been slipped beneath Kit’s cloak. A quill he guessed it a swan’s quill, by the strength and color the tip cut to a nib but with the vanes of the feather unstripped.

“I think not,” Will said, hunching to twist his hose smooth at the back of his knee. “A pen?”

“Indeed.” Some unidentifiable thrill ran through Kit as he held it, a sensation like beating wings, and with it came undefinable sorrow and joy. He set it on the table near the bed but was unable to resist one last, soft touch. “I wonder how it found its way onto the coverlet. Who’s there?” Tucking his shirt hastily into his untied breeches as a second round of knocking commenced, he hastened to the door and unlatched it.

Morgan stepped inside and regarded Kit with amusement. “So you rise to greet the nightingale, and not the lark?” And then, over his shoulder: “Good day, Master Shakespeare.”

“Your Highness.” Will came forward, fastening his buttons one-handed. “A fine reception last night.”

“I thank you. There’s dancing tonight,” she offered, brushing past Kit to lay a hand on Will. “I wished to speak with thee. Kit, Cairbre wishes your attendance when you are decent.”

Kit swung his cloak up. “Will, wouldst care to accompany me?” I am not leaving him alone with Morgan le Fey.

“I shall send him along when I’ve finished with him,” she promised. “Don’t worry. It shan’t be long.”

Kit looked from one to the other: Will had a certain bemused curiosity on his face, and Morgan’s tone was one step shy of command. He sighed and finished dressing. “Very well.” He bowed over Morgan’s hand. “Treat kindly with my friend, my Queen.” Knowing she would hear everything he put into the title, both promises and obligations.

“I shall be sure to,” she answered, and there was nothing for it but to excuse himself and go.

For all that beauty that doth cover thee,

Is but the seemly raiment of my heart,

Which in thy breast doth live, as thine in me:

How can I then be elder than thou art?

WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE, from Sonnet 22

”Now, Master Shakespeare,” Morgan said, after the door drifted reluctantly closed behind Kit, “this illness thou’rt concealing so effectively. We’re going to discuss it.”

Will blinked and sat down on the edge of Kit’s bed. “Not such effective concealment if you noticed it in the span of a few hours acquaintance.”

“I am she who notices such things,” she said, dark eyes sparkling. She settled on the floor, her gown puddling around her, and drew her knees to her breast. “What afflicts thee, other than the tremors and the shortened stride?”

“Lack of balance,” Will answered, amazed at how easily the words came. Do not trust what the Faeries offer,he reminded himself. “Easy exhaustion. My throat aches, as do my breast and back, and I have no appetite. Of late I notice the palsy in my left hand too.”

“The next stage of the illness,” Morgan said, resting her chin on her crossed arms and her knees, “is likely a more shuffling step and a nodding palsy, and a paralysis of the face. If it follows the course I’ve seen. Thou’rt no more likely to suffer dementia than any man, for what comfort it offers.”

“Likely,” Will answered. “My father is well aged and still in his right mind, though ill for years. I have my hopes.”

“Thou shouldst.” She rose, uncoiling, posed for a moment like a caryatid, and as she came toward him he saw her feet were bare upon the carpets. The loose gown caressed the heavy curve of her hips and breasts such that it left Will’s throat aching more than his illness could excuse. “I’ve aught for thee: a tincture of hellebore and arnica, and powdered root of aconite.”

“Monkshood?” Will thought of nodding blue flowers. “All poisons, Your Highness.”

“Aye,” she said. He would have stood when she came before him, but her long-fingered hand on his shoulder pressed him down. “Herbs of great virtue are often dangerous.” She smoothed her fingers under the line of his jaw, where his blood fluttered close to the skin, and felt of it for a moment, unhurried.

She smelled of something sharply bitter and over it a musky, resinous scent: warmed amber, he thought. The frustrations of the night flooded back at her touch, and he prayed she thought the shiver that ran through him was illnes sand not the raw, physical reaction that it was. Always a weakness for older women.He bit down on a chuckle. Much older.

She nodded and stepped away, her hand lingering for a moment. “I’ve brought a salve imbued with amber oil and camphor as well, to anoint the sore places. Some say it helps.” A facile shrug, and then she dug in her pockets for a tin box, a stoppered bottle no bigger than an ink horn, and a casket of carven stone. “We can try poison nut if none of these avail. Thou needst be cautious of the dosage: there is no remedy for monkshood or arnica poisoning, and neither is a pleasant death.”

Will held out his hands: they trembled less as she laid each gift in his cupped palms. “Thank you, Your Highness. You will show me how?” She nodded and went to the fireside, leaning against the edge of the hearth, watching him with a sort of birdlike brightness. He stilled his face to hide the longing in it.

“None of this is a cure, gentle Shakespeare.”

“I understand.” Curiously, he examined the bottle; it was carven from the tine of a stag’s horn, and the stopper was finished with a knotty gray pearl. He laid it on the bed beside him, along with the other trinkets. Your Highness.”

“Ask it, William. I have little time for reticence, as Sir Christofer will no doubt inform thee.”

“Why am I permitted my freedom and vouchsafed your aid, and that of the Mebd, when my friend Kit is so obviously bound here against his will, and indurance?”

“A good question, she said, and went to find glasses on the sideboard. “Thou shouldst not too much drink ale or wine with those herbs; a little will not hurt, but be sparing. But I can offer thee a drink of lemons and ginger.”

“A good question that will go unanswered,” he said with some amusement, smiling as she placed the cup in his hands. It steamed, and the metal warmed his palms: more casual witchcraft.

“Nay,” she said. “I’ll answer thee.” She sipped her own drink, and Will only held his for a moment and watched her face and the way her hair moved against her cheek, showing bands of silver among the black.

She said, “Because thou art of more use to Faerie in the mortal realm than thou art here, and Sir Christofer has that in him which we need, and can bargain with, and can use as a weapon. And thus we keep him here.”

“Has that in him, his magic? His poetry?”

“No, though we have our ways of making profit on that.”

“Does he know this?”

“He knows we have uses for him. He knows what some of them entail: his poetry, his plays. We use him as your own Gloriana did and there is more to it, of course.”

“And you have not told him.”

“Because,” she said, pressing the back of her hand to her eye, “he is not ready to know. Thy Kit Marley is a deeply broken thing, gentle William, and I do not think he could bear the knowledge of what use he has been put to.”

Will’s hands tightened on the cup. He lifted it to his mouth and tasted the sweetness of honey, the sharpness of ginger, infused with a silvery aftertaste. Her candor left him nauseated: the ginger helped. “What use is that, Your Highness?”

“No,” she said, after a considering stare. “I do not believe thou couldst keep it from him long, even an thou understood why it must be kept. Suffice it to say he is safer with us, and kept distracted with small tasks.”

“He’s not a man for small tasks, Your Highness.”

This smile sparkled, parting her lips for a low, sugared laugh. “Perhaps not,” she answered, setting her cup on the mantel and strolling toward the door. She opened it and paused within its frame, turning back for a parting smile. “But then, neither art thou, I consider.”

Will paused in the doorway to the conservatory, blinking in the light as its occupants turned to face him, and then blinking again to bring the splendor of the enormous room into focus. Music surrounded him, an eldritch sort of a reel on two flutes and viola; he gazed about in wonder as he paused atop the broad, time-hollowed marble steps. Some vining plant a type of fig, he realized, for the fruit that hung in purple-black profusion along its stem ascended a trellis, contorted branches a latticework against the crystal of the ceiling. A wisteria’s waterfall blossoms dangled among the fig’s glossy leaves, and all about the glass-domed marble space were fountains and benches and statuary, a profusion of half-private niches and mossy grottoes.

A small group of people both nearly human and quite outlandish gathered by the splashing fountains: Kit and the bard Cairbre in their gaily colored patchworks, and beside them the snake-tailed Amaranth. There was a foppishly dressed gallant with a stag’s head on his shoulders, shiny above the ears where he must have shed his antlers, and Robin Goodfellow perched on the head of a statue, reed flute raised to pursed lips and his ears waggling in time.

Will did feel better for Morgan’s herbwifery, he realized; the ache across his shoulders ebbed, and his hands shook less as he took the banister to descend, hushing his footsteps so as not to disturb the musicians. Kit caught his eye over the restless motion of the bow, offering a smile that brought with it a frisson that Will could almost convince himself was aversion. Or should that word be fascination, Will?

He paused outside the circle until Kit, Cairbre, and the Puck lowered their instruments, then joined the polite applause. Kit, that smile still intact, handed his viola and the bow to Amaranth, who settled it under her chin amidst much inconvenienced hissing from her hair.

“Well played,” Will said. Kit shrugged it off. He laid a hand on Will’s shoulder and drew him gently aside, where the sound of the fountain and the flurry of music would cover their speech. “I’ve not much to do but practice and play the Prince’s favorite. How went your interview with my mistress?”

“She is most gracious,” Will answered. “And most mysterious.”

“I hope you have been careful what she has asked of you,” Kit.

“As careful as a man may be, where he owes his life.”

“Aye, there’s the rub.”

“Tis not the rub that concerns us so much as the result.” Will chuckled, dabbling his hands in the fountain. He leaned back, rested against the edge, remembering the paleness of Kit’s scars. The man’s entitled to nightmares,he thought. He’s also entitled to the truth of what Morgan said of him: as well she knows I won’t be used against my friend.

“She hinted at things that troubled me, my friend.”

“Sorcery and subtlety.” Kit snorted, turning to sit on the marble edge, shoulder to shoulder with Will and on his left. “Did she tell you it was she who ensorceled me, when first I came to Faerie?”

“No. And yet she released you?”

“After a fashion. Or I won my way free. I am still bound here, though.”

Will raised his left hand to brush his earring.

Kit nodded. “I envy you that, a bit. It seems I can be gone from Faerie three days, perhaps four, before my body begins to fail. An unkind sentence. I comfort myself that at least I left no family, save that in Canterbury.”

What dost thou then think I am, Kit? And the Toms, and Mary and Robin, and Ned Alleyn?But he nodded, and bumped Kit’s shoulder with his own. “She also hinted and wisely said she would not say more, as I might run direct to thee with the tidings,” a deprecating laugh, “that thou wert bound, somehow, still. She suggested that there was a power in thee, something trapped and broken.” He moved to see Kit’s profile. Kit had put his blind side to Will, Will realized with a rush of affection.

“She has a gift for manipulation,” Kit said. “But she does not understand, always, mortal men.”

“I see.”

“What did she say, exactly?”

Will drew a breath, watching Amaranth rise up on the tower of her tail, her scales catching the light that rippled from the fountains until it seemed she shone.

“She said that I was free to go because of being more use in the mortal world than here, and that you have that in you which she needs, and might bargain with, and may find to be a weapon. And that you were too deeply wounded to be told this secret, because it would damage you further to know.”

“I see,” Kit said. “Tis so satisfying to have the trust and good faith of one’s patrons.”

Will held back a laugh at Kit’s dry, weary tone. “Wilt beard her on this?”

“Morgan le Fey? Might as easily draw the claws from a lion’s paw as secrets from that one. She’s fair as thorn in bloom, and twice as daggery. No. I’ll pursue where I can.” Kit folded his arms across his chest, the angle of his chin telling Will that he watched the Puck cavorting about the shoulders of Hercules. He sighed. “Sweet William. How did we ever get from there to here?”

Will shrugged. “Where? London? Where is here, then?”

“Sorcery, intrigue, intelligencing, Faerie.”

“Poetry.”

“Poetry is how we got here? Who would have thought poetry so dangerous?” Kit kicked one heel up, resting it against the base of the statue. “My father made shoes. Yours made gloves. There’s a certain symmetry there, and to ending up here.”

“The Cobbler’s Boy, the Glover’s lad, and the Queen of Faerie. I hope this isn’t an ending.”

“I was hoping for happily ever after in wealth and contentment.”

“It should be a ballad.”

If I know Cairbre, it will be. A facile comment, but Will thought there was more behind it. Kit hummed a familiar melody, and sang under the rise and fall of the flutes and the viola: ‘ALL hail the mighty Queen of Heaven!’