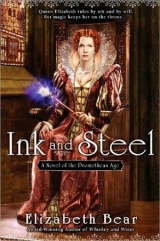

Текст книги "Ink and Steel"

Автор книги: Elizabeth Bear

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 14 (всего у книги 29 страниц)

Will wished suddenly he had not given his wine away, remembering Kit’s voice on another occasion, in the dark kitchen of Francis Langley’s house.

“Still, an Inquisitor. I’m tempted to count it some species of honor.”

“Oh. It bodes not well.” Kit shoved the cup back at Will with still some wine in it. “You must see to it that Francis gives Thomas Walsingham the name. Or better, see to it yourself. I’m sure your status is enough, these days, that he would grant you an interview if you sent him a note.”

“You sense a move against the Queen?”

“I can see no reason otherwise de Parma would be in England. You’ll want to pour wine, if you’ve finished that.”

“More wine?” But Will stood, and collected Kit’s cup as well, and again filtered the dregs through cheesecloth to produce something potable.

“Here.”

“Sit,” and Will sat. “What is it?”

“The reason Elizabeth protects Oxford. And what will make your task all the harder, though Essex has o’erplayed his hand.”

Will studied Kit’s face, its deadly earnest placidity except for a sort of valley worn between the eyes. “I listen.”

“You know Edward de Vere was raised as William Cecil, Baron Burghley’s ward after the sixteenth Earl of Oxford died. At the Queen’s request.”

“I do.”

“This does not leave this room.”

“I understand.” Kit drank off his wine at a draft, and plucked the dagger from the tabletop to clean his nails.

“Oxford is Elizabeth’s bastard son.”

Mortimer:

Madam, whither walks your majesty so fast?

Isabella:

Unto the forest, gentle Mortimer,

To live in grief and baleful discontent;

For now my lord the King regards me not,

But dotes upon the love of Gaveston.

He clapshis cheeks and hangs about his neck,

Smiles in his face, and whispers in hisears;

And, when I come, he frowns, as who should say,

“go whither thou wilt, seeing I have Gaveston.”

CHRISTOPHER MARLOWE, Edward II

Kit tugged his hood higher. “Latch the door after I leave.”

Will folded his arms. “I fail to see what errand could be of so much import that you must risk yourself in the street.”

“Some things,” Kit said, “a man must simply do. I’ll return by dawn. I swear it.”

“I’ll be at the Mermaid if you want me, then,” Will said, shaking his head in stagy frustration.

Kit walked through London with a feeling in his breast like freedom, his left hand easy on the hilt of a silver rapier forged as hard and resilient as steel. Carts clattered in the twilight, whorish girls and boys called from doorways, and men and women hustled home from market or out to taverns for their dinners. A commonplace scene, London in the sunset, and one at odds with the determination that coiled in Kit. He kept his eyes downcast and let his hair fall in front of his face, concealing as best he could his eyepatch.

A sunny day for staging a vengeance tragedy, Marley. Tis not vengeance,he told himself. Tis preclusion.

Two hours walking and half the Faerie gold in his purse bought him the location of Richard Baines home: a house rather than a lodging, on Addle Street. He’d done well for himself. Kit skulked through an alley almost too narrow for his shoulders to pass without scraping the wall on either side. The house had a little garden: he hoisted himself to peer over the wall, but every window was darkened. Damn. At the Sergeant, do you suppose?A bell tolled nine of the clock, and he let himself drop on the outside of the wall.

Wherever Baines is, Fray Xalbador will not be far behind.

Kit stroked the hilt of his sword again, thinking perhaps he should try his hand at finding Oxford, instead. A dead man may accomplish many things a live one might balk at. But he wanted Baines blood, that was the truth, and wanted the false Inquisitor’s more. He could scale the wall and lie in wait, since it seemed not even a servant was at home. Or he could go in search, aimlessly pacing. His feet decided for him. He walked through the much-thinned crowds, amused at how little apprehension he felt at strolling London’s streets in the darkness. Dead men lay their burdens down. But it was a lie, and he knew it. With an intelligencer’s assessment of risk and reward, Kit knew that Fray Xalbador was worth Kit’s own lifeblood to put an end to. More than worth. Might as well trade Faerie gold for a good English sovereign. But as much as Kit would have liked to hunt Robert Poley to his death at the Groaning Sergeant, Kit knew his life wasn’t worth Poley’s. His secret wasn’t even worth Poley’s life. Surprised at a familiar voice, Kit stopped, looked up, stepped away from the square of light cast by an open door. A slow baritone, with something of the luff and fill of thoughtful sails behind it.

“Chapman,” he murmured. And indeed, his wandering footsteps, no doubt primed by Will’s words on where to find him, had led him into Cheapside and onto Bread Street. As he looked up he saw George Chapman’s portly girth silhouetted against the open door of the Mermaid. Laughter followed Chapman’s unheard bon mot. Kit drew into the shadows, hoping Chapman didn’t think him a cutpurse or lurcher lying in wait. He need not have feared: Chapman never saw him, but set out whistling down the street, swinging a stout stick and holding a half-shuttered lantern.

Kit glanced longingly at the sharp-cut panel of lamplight on the cobbles, and swore. He could hear Will’s laughter now, too, and someone else, Tom Nashe? a voice cut clean by the closing door. He turned on his heel and followed Chapman. At least I can see him safe home. Arrant fool, walking through London alone after curfew.

But Chapman moved east, and Kit followed at a little more distance, now curious more than worried as his old friend let that stick tap lightly on the cut stone kerb.

Dark houses loomed: a crack of stars were visible only directly overhead, and only a few lights gleamed through the slits in shutters, stars of a different sort. The rats grew bolder after dark, and twice Kit heard the squealing of their private wars.

Chapman was walking to Westminster Palace, a goodly night’s jaunt. The lantern was a godsend: its light both steered Kit and blinded Chapman, so Kit need fear neither recognition nor the loss of his quarry in the dark. He fell back a little as they passed Blackfriars: there were carriages in thestreets, parties of walkers, and groups of armed men to keep the Queen speace. King’s Street was quieter, once they passed through the gates, and there was little traffic beyond Charing Cross.

Kit turned once at a footstep behind him, wary of a sense of being watched, but he saw only a few figures. Another lantern-decked carriage rattled over the cobbles, forcing one pedestrian against the wall. Probably just Morgan watching me through her damned Glass. Matched bays drew the coach a two-in-hand and the gelding on the near side had one white sock on a hind foot, which flashed in the lantern light along with the footman’s livery.

Oh, that’s just too much of a coincidence.Kit stepped up his pace, eyes trained forward. But of course it wasn’t a coincidence at all. He had been following Chapman. And Chapman had been en route from supper and conversation with his friends and fellow playmakers to meet his patron. His patron, who had been Kit’s patron as well. And friend. And more. Thomas Walsingham.

The June night was warm, the air humid enough that it felt as if Kit walked through veils of silk that clung and slipped. He followed the slowing carriage as he had followed Morgan, one footstep and then another. But this was thoughtful rather than blind obedience. The meaning comes in the silences. Momentum comes from the instant before the foot leaves the ground.

The white-footed gelding stamped as his mate jostled him, tugging the rein as the coachman drew them in. Kit heard the creak of leather, the rattle of iron-shod rims on stone. Someone hallooed Chapman; a lantern flickered. Kit laid one hand on the wall and watched from the shadows, as if turned to stone.

Or salt,he thought, as the coach door opened. I could wish that. A pillar of salt, to melt in the endless London rain and flow down the Thames to the ocean. Like a river of tears. Oh, stop it, Marley. That’s not even an original image.And still he could have wept at the contrast between what he felt, now, suddenly, that had been so long stepped upon and the desperate, thoughtless, compliant passion that had marked his loves in Faerie. Loves? How couldst even thou have mistaken that for love, Kit Marley?More to be ashamed, for he knew what love was. It was the thing that held him now, a breathless kind of clarity that kept him in the shadows, waiting for one last glimpse of the man whose life and home he had shared before.

The footman moved to assist a tall, ginger-haired woman in a flat-fronted French gown down the iron step. Kit’s breath lay like pooled lead in his chest as she lifted her skirts and set her pattened feet upon the cobbles with a clack. Audrey Walsingham. She stepped away, gliding toward Chapman, who leaned on his cudgel as if it were a cane and swept a thoroughly creditable bow. The carriage door stayed open, the footman at attention. Kit heard Chapman’s murmur, Mistress Walsingham’s tinkling laugh as he steadied her toward the palace.

Leave, Kit thought, and came a half step closer to the carriage lights. Long legs in silk hose, a well-turned calf strong from time spent on horseback. The hair was dark by lamplight as he grasped the rail and stood, settling his doublet with a shrug of muscled shoulders, but Kit knew it would gleam with copper highlights in the sun. The footman stood aside as Thomas Walsingham descended, swinging the door shut with a casual gesture that brought Kit’s heart into his throat. He stepped forward again, and halted his motion in midair. What art thou imagining thou mightst do here, Marley? Apologize for thinking Tom conspired with thy killers? Explain that Frazier and Poley lied, and thou thyself never practiced against the Queen? Throw thyself at his feet and kiss the stones between his shoes? Beg him to take thee home to Chislehurst and swive until thou bleedst, stay from Faerie and die in his arms like a selkie kept from the sea, while the lovely Audrey cossets and possets thee?

It had a certain appeal, like Dido leaping into the flames, like Cleopatra up to her elbows in a basket writhing with asps. Kit set his foot in the print he had lifted it from, and stayed in the shadows, his right hand closing on the collar of his doublet as to tug it open and cool his throat. Such a small motion to so betray him.

Tom must have caught the gesture from the corner of his eye. He turned like a splendid stallion, nostrils flaring, six inches of steel flashing in the carriage light as his right hand gripped and half drew his sword. Who goes? A low voice, not loud enough to turn the heads of Chapman and Audrey, but enough to bring the footman around to flank his master. Kit smiled in recognition of the caution. Yes, Tom. Get the lady in the gates along with her escort. You stay and handle the trouble, and she none the wiser. Besides, the palace is close enough to rouse to a cry of murder in the street. But that could be embarrassing if it were a false alarm, couldn’t it?

He glanced over his shoulder as Tom and his man came a few steps closer. The coachman kept a tight rein on the stamping bays, but he turned to look, and Kit knew there was a loaded pistol in a box behind his seat. The way was deserted on either side, except for the figure who had dodged the carriage some distance away and hurrying forward with running footsteps and Chapman and Audrey, who would be out of casual earshot by now. A cross street lay a few steps away: Kit could turn, fly, and be gone before Tom glimpsed his face

An excellent plan.

“What is thy name, villain?”

If I had ever been able to walk from that voice.

“Not a villain.” Kit took two short steps forward, to the edge of the lanternlight, and tugged his hood back with his thumbs. The gesture revealed his sword, and showed his hands well away from it, and Tom’s grip on his own hilt slackened. And then Walsingham’s jaw dropped, and the knuckles grew white again.

“Rather a gentleman, Tom.” By his expression, the footman didn’t know Kit. One small mercy. Tom’s jaw worked, but no sound emerged. Kit couldn’t spare a glance for the figure now running toward them. “Tom, you must know. Frazier lied to you. I never did what he said.”

“How do you know what he said?” Kit jerked his chin at the candlelit windows of the palace. Tom’s face grew so pale Kit could see by lantern light. And Will Shakespeare drew up ten feet away, wobbling with the force of his stop, his arms widespread for balance as if he had suddenly realized he was about to run between two armed men.

“Master Walsingham,” he said softly. Tom shot him a level, almost mocking look. Kit knew it, and breathed a little easier. “The playmaker Shakespeare. I take it you knew about this?”

“Will nodded.” Tom took his hand off his sword and turned to the footman. “Jenkins, see that Master Chapman and my wife understand that I will be delayed. Perhaps as much as an hour.”

“Sir.”

Audible relief filled the man’s voice as he took himself away from matters he did not understand and vanished in pursuit of his mistress.

“Now,” Tom said. “Into the carriage, for lack of a tavern. Pity, for I am very much in need of a drink, but I can’t stand talking in the street with a player and a dead man.”

Kit tried not to notice how Tom’s eyes lingered on his face. He turned his head to hide the scarred side, but could not stop a shiver when Tom took his elbow and almost lifted him into the coach. Will slipped on the step, but Tom steadied him too, and Will shrugged and smiled his apology. Kit flinched at the misstep. He prodded the ache in his chest, and knew.

Murchaud was right. I can’t stay here.They took their seats and Tom rapped on the coach roof. Wheels rattled on the cobblestones, the carriage swaying on its straps.

“Where are we going?” Will asked. “There and back again,” Tom answered. “Twice, if we need more time.”

Kit laughed. “You haven’t changed.”

“You have. Ingrim told me the Queen ordered your death. Through Burghley. Poley showed him a writ, and had him burn it.”

“Would Ingrim know a forgery?” Kit rubbed his eyepatch.

Tom shrugged, leaning forward to speak over the creak and clatter of thecoach.

“He should. There’s testimony, too.”

“Do you believe it?”

“When Her Majesty more or less forbade anyone to examine your death, and pardoned your killers, what else could I do? Tell me you re no agent of Spain, or the Romans. Or James of Scotland. Tell me where you’ve been. The Continent? It has been kind to thee. Thou hast not aged a day. Tell me thou art loyal, in thine own voice, Kit, and I’ll believe it.”

“I was loyal to the Queen, and the Queen gave me my life,” he answered. “And then she returned to me mine oath. And now I am a free man. Beholden to another. But faithful in my dealings with England, I vow.”

Tom glanced at Will, who had withdrawn into a corner. He watched without speaking, making himself small.

“And how does Master Shakespeare come into the ciphering?”

“I followed Kit,” he said, folding his arms over each other as if he were cold. Kit felt him shiver, where their shoulders brushed. “He trailed Chapman from the Mermaid.”

A searing glance told Kit that he would have some explaining to do for his carelessness.

“I had stepped outside to catch George and remind him of somewhat,” and Tom smiled, and Kit knew he was deciding to let his actual question go unanswered.

Kit cleared his throat. “Tom, I can trust you?”

“As a brother,” he said, and squeezed Kit’s leg above the knee. Kit watched his face, and saw no flicker of deception.

“Very well,” Kit said. “This will take longer than a coach ride. How much has Sir Francis told you?”

In the half-light of the swinging lanterns, Tom’s face grew grim.

“Not enough, apparently.”

Kit nodded. “He’s dying, Tom. For certain. And Burghley too.” He lowered his voice. “And Her Majesty grows tired.”

“Her Majesty has reason.”

“They are old,” Kit said, knowing that the words carried every trace of treason that his enemies could have wished. The coach’s jolting seemed ready to drive his spine through his skull, but he kept on, though Tom sat back as if to increase the distance between them.

“There’s a reason your Ingrim put a knife in mine eye. Duped by Skeres and Poley, or conspiring with them, there’s time enough for that later. There’s a reason Oxford and Essex move against the Queen. The old Queen must have an heir.”

Will’s elbow banged against the side of the coach. “They are old. And we are young. Comparatively speaking.”

“Fellows!” Tom’s shock was evident.

“Listen.”

And somehow, Tom did. Kit drew a breath, but Will cut him short, surprising Kit with the depth of his understanding.

“When Burghley and Sir Francis are gone, their successors can be thee and me, Master Walsingham. And Robert Cecil, and Thomas Carey’s son George. Or they can be our enemies. Men like Poley and his masters. Baines. And the Spaniard.”

“What of the Queen?” And the Tom stopped himself before he said the unfavored word, succession.

Kit shrugged. “In any case, you must step into Sir Francis shoes. And quickly.”

Tom turned his face into the light. It illuminated his silhouette, limning lips and nose and brow in gold.

“He’s barely now begun to warm to me again, Kit. We did not speak o’er much after your murder.”

“Mend it soon,” Will said. “Or not at all.”

“That bad?”

“We must sire our own conspiracy.”

Kit could see Tom tasting the word. “Conspiracy.” He realized with shock that threads of silver wound Tom’s hair.

“Kit, and what of thee?” Kit closed his eyes on pain, knowing the answer. Knowing what it had to be, as soon as Will had effortlessly picked up the thread of his thought, and explained it. Known from the way Will had tailed him so deftly that Kit, Kit had barely even known he was watched, and how Tom had put Audrey and Chapman out of harm’s way without taking time to think.

“I am dead in this world.” Everything I could do, they can do better. Sweet Christ, I love these men. Better to remember them young and fierce, than like Sir Francis.

“Tom, your man Frazier was duped?” Tom’s lips twitched. He nodded once, his eyes focused on Kit’s scar.

“I am commanded elsewhere, Kit said.” You’ll outlive it. Outlive all your loves and hates, and when your mortal span is past …“Thou wilt not see me again. Nor shalt thou, Will, I warrant. But I leave my Queen in capable hands.”

“Kit,”– Two voices as one, and the tone of them warmed him even as he shook his head.

“I am commanded elsewhere,” he repeated. “And so tonight I shall give you everything I know.”

Kit laid the palm of his right hand on Will’s mirror and pressed forward against a sensation as if jellied mercury flowed to admit him. He glanced over his shoulder at Will and at Tom Walsingham standing beside him, fixing the two men’s faces in his memory. They had kissed and clipped him as brothers, and that embrace was a sort of hollowness resting on his skin. Dead men must trust the living to get on with their business, I suppose.

“I’ll write,” Will said.

“I don’t think I shall reply.” Kit looked away before Will’s expression could change. “Tom, give my love to your wife.”

He pushed through the mirror. He emerged in the corridor between the curtains that flanked the Darkling Glass, tendrils of crystal loathe to resign their grips.

No sooner had his boot touched the tiles than he bowed his head, startled, and dropped a knee, his silver scabbard-tip clinking and skipping. The Mebd stood over him: he had almost stepped into her arms. A scent of roses and lilacs like a breeze from a June garden surrounded him; he lifted the embroidered hem of her robe to his lips, heavy cloth draping his fingers.

“Your Majesty.”

“Sweet Sir Kit.” He heard the smile in her voice and clenched his teeth in anticipation of a hammer blow of emotion. Her hand touched his shoulder and he almost fell forward, realizing as he put a hasty hand to the floor that he had been braced against a raw spasm of desire. It never came.

“Mayst rise.” He did as she bid, keeping his eyes on the woven net of wheat-gold braids that lay across her shoulders, pearls knotted at the interstices. She tilted his chin up with flowerlike fingers, forcing him to meet her eyes.

“Needst not fear our games this night, Sir Poet.” She released him and stepped back, her fingers curling in summoning as she walked on. “We’ve been most wicked to thee, my husband, my sister, and me.”

“I’ve known wickeder.”

The pressure of violet eyes in her passionless oval face was almost enough to force him against the wall.

“Thou dost wonder at thy place in our court.”

“I do.”

She smiled, and reached into her sleeve. “When our royal sister Elizabeth dies, things will change.”

“Your Highness?” He stepped back as she drew out a long fluid scarf of transparent silk and twined it between her fingers. It shifted color in the light, shimmers of violet, green, and gold chasing its surface.

“And there will be a war. If not that day, soon after.”

“I am a poet, Your Highness. Not a soldier.”

She smiled at him, and reaching out, wound the scarf around his throat three times, letting the silk brush his face, softer than petals.

“For thy cloak, she said. Give me a song.”

“What sort of a song?”

“An old song.” She started forward again, and he paced her, reciting the oldest song he knew

‘… Young oxen newly yoked are beaten more,

Than oxen which have drawn the plow before.

And rough jades mouths with stubborn bits are torn,

But managed horses heads are lightly borne,

Unwilling lovers, love doth more torment,

Then such as in their bondage feel content.

Lo! I confess, I am thy captive I,

And hold my conquered hands for thee to tie.’

“No,” the Mebd whispered, interrupting him with a hand on his wrist and seeming for a moment a woman given to softness rather than a cold and mocking Queen. “Not that. An English song, for thou art an Englishman.”

“Thomas the Rhymer?” he suggested waggishly, wondering if she would let him press the advantage. A gamble, but they that never gamble have no wit.

“Perhaps not that either. It’s no mere seven years thou wilt serve.” But she smiled, an honest smile, and tilted her head so her braids moved in disarray over her neck.

“I know it.” He nibbled his mustache. “I’ve made my farewells, Your Highness. I’m ready to set it behind me.”

“Thou shalt find it easier. And Morgan has released thee from what bondage she held thee in.”

He blushed. “It influenced my decision.”

“Of course.”

“Free, and myself,” he said. “But never free to leave.”

“No.” Her sorrow was not for him. Never that. They walked on in silence. She led him through tall, many-paned glass doors and into a garden that smelled as she did of lilacs and roses.

“Mortals can be enchanted,” she said, gravel rustling beneath her slippers and turning under the brush of her train, “but they cannot truly be bound the way the Fae can be bound by their names, by iron. Every knot in my hair is a life I possess, Sir Kit, a Faerie entangled to my will forevermore. I could not bind thee so. Nor canst thou be released by the gift of a suit of clothes, or a new pair of shoes. So thy folk require more careful handling. Tis better to let them grieve at their own rate, and leave at their own rate, too.”

She smiled, and recited a scrap of song of her own. “‘Ellum do grieve, Oak he do hate, Willow do walk if yew travels late.’ Dost know that one? No Ah, well. Thou wilt learn it, no doubt. Do you toss like an elm, or break like an oak, Sir Kit?” She stopped and bent to smell a rose.

“This war that you expect, Your Highness.”

“Aye?”

“How will it be fought?”

“Oh,” her smile was lovely. Even through vision unclouded by fey magic and glamourie.

“With song, Sir Poet. With song.”