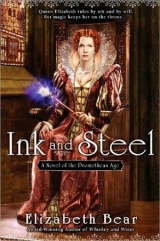

Текст книги "Ink and Steel"

Автор книги: Elizabeth Bear

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 12 (всего у книги 29 страниц)

When Kit stood to give his poem on Cairbre’s signal he chose something that spoke of the pastoral delights of summertime and never a chance of sorrow. But when he returned to his rooms after dinner, he worried an iron nail loosefrom his old riding boots, and slipped it into the sleeve pocket of his doublet, and felt just a little better for it.

‘Sweet Romeo: I apologize for the vagaries of my correspondence. My new masters it seems do not approve entirely that I maintain my friendships from service taken before but in this cause I am defiant. That I am your true friend do not doubt. I thank you for the word of little Mary & her nestling, that they are well. I will watch over you as my ability permits, & your letters (& those of FW) relating the situation in London fall most welcomely into my grateful hands. There is some change in my circumstances, not serious of yet but prone to developments, in which case you might say I am at mine old works again, & there are revelations that may suspend correspondence. These circumstances include the following: that I have been unfair in my judgement of TW, & rather those charges should have been levied at that abominable bastard in the peascod doublet he no doubt imagines conceals his paunch, you will know of whom I refer. Also, it is with sorrow that I must relate that he who I have considered your greatest ally (again you will know) is gravely ill. I have not managed a visit, or more than a word & a note, but I believe that the poison administered these four years since is at work again, & I do not think my dear friend will last through the winter in the lack of Doctor Lopez’s care. This places you in graver danger than I can express. It is imperative that Peascod-doublet not learn we know of his duplicity. Her Majesty, as you know, though it were sedition to speak it, grows in melancholy with the passing of each old friend & each treasured counselor. I cannot imagine that to lose mine old master will lie easy on her, for all their difficulties after the death of Mary Queen of Scots, & you must know it will make her more open to Essex & his machinations: the patron they have sought for you, Southampton, is useful as a link to Essex. There are rumors but I am sure the conclusion lies within your powers. FW s illness means also we must find another path of correspondence. Will you have a looking glass placed in your chambers? Steel-backed is best for these purposes though flawed at reflecting, & less dear than silver. I pine without your company.’

‘Post script: Amusing to put the speech on Queen Mab in the poor lad’s mouth, then have him stabbed under his friend’s arm. I wish Tricky Tom Watson were alive to see: he so would laugh. It reminds me of the time Will Bradley would have had my head if Tom hadn’t got his blade between us, as I am sure youintended it to. Poor William should have known better than to start a quarrel with a poet; we travel, like starveling dogs, in packs. It saddens me to think now that all three of us who fought that night are dead. Your loyalty warms me in a colder world than my words or yours could express, but you must have caution in these things, for all it flatters me to be remembered.’

‘Dearest Mercutio, London continues much of the same. Recusants and moneylenders pilloried in the north square, RB after me to pen more plays though I have given him four this year already. And I have spoken with FW, who is yes gravely ill and failing. He says he also had word from you that his cousin is genuine, and the peer you dub Peascod-doublet more truly the villain. I should tell you that TW spoke with me concerning you and I and the craft of playmending sometime back. I gave him nothing then. In the light of new intelligence, is it your estimation that he may be trusted? I asked RB to consider that slanders leveled against your name may source themselves in EDV. He thinks rather they come from Gloriana, though why she might wish your name blackened I know not. MP and her son are well indeed, and under my care. A story is making the rounds at the Mermaid that a half-dozen sober Londoners witnessed the blood-soaked ghost of Kit Marley on a Cheapside street in the rain this summer, prophesying doom on those who murdered him. The better versions of the story have lightning dancing around the ghost’s shoulders like a cloak, a naked sword in its hand, and a whining Robert Poley cringing at its feet.

Of course, no one believes it. Where would you find six sober Londoners all at once? There are a few stories the sober Londoners tell of EDV as well. I asked RB of the Spanish choirboy he’s rumored to have imported, and RB assured me it was basest slander. The choirboy was Italian. Horatio something. I suppose that’s one way to stick it to the Papists. Your true Romeo.’

Orlando:

My fair Rosalind, I come within an hour of my promise.

Rosalind:

Break an hour’s promise in love! He that will

divide a minute into a thousand parts, and break but

a part of the thousandth part of a minute in the

affairs of love, it may be said of him that Cupid

hath clapped him o the shoulder, but I’ll warrant

him heart-whole.

WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE, As You like It

Will stepped down from a hired coach weary, bruised to the bone, sorely afflicted with chilblains, and nibbled by fleas. He’d fallen uneasily half asleep with his fingers protruding from under a carriage robe clutched to his chin. He worked them now, trying to bring sensation to cold-chapped skin. The coachman liberated his luggage and slid it down beside the wheels; the ground was too frozen for the trunk to be damaged by mud. The tired bay snorted. Will skirted the horse nervously, and caught one end handle on the trunk to drag it toward the cottage with its close-thatched roof. He closed his eyes, smelling kindled fire and baking bread, and stopped himself a half gesture before he rapped on his own front door. Instead he breathed deep, then pulled the latch-cord and shouldered the green-painted portal open, letting his trunk bump over the threshold.

“Annie?” She straightened and turned to him, aproned and dressed in good gray woolen, leather shoes on her stockinged feet against the winter chill of the rush-strewn floor, her befloured hands spread wide. Will. She stepped closer. Will kicked the door shut and bumped it with his heel to make certain of the latch. Leaving his trunk half blocking the threshold, he met her halfway between the door and the table and caught her wrists, holding her whitened hands back when he kissed her mouth. She giggled like a girl. He wiped flour off his cheek when he stepped away.

“I’ve a rental house for you to look at.”

“Annie, let a man get his boots off,” he protested, and she laughed again. “I’m famous, wife. Romeo and Juliet. Dost care?”

“I’ll read your plays,” she said stolidly, turning to wash her hands, when they bring you home again. He came and poured the water for her so she would not beflour the ewer, and watched her hands tumble over each other like courting birds.

“The bread smells wonderful.”

“Wonderful enough to wake the children, do you suppose?” She glanced at him sideways, drying her hands on her apron. “Still slugabed?” He smiled, looking up at the loft. “Did you tell them I was coming?”

“I …” She stopped. “I didn’t want to disappoint them.”

“Ah.” The sour taste was no more than a night spent in the Davenant’s Inn before resuming his coach seat to finish this journey.

He nudged his trunk out of the doorway, pushing up a thin ridge of rush stems. Annie’s eyes were on him, kinder than he had any right to.

“Do you think I can get Hamnet down here over my shoulder before he wakes, the way I used to?”

“He’s bigger than you remember Will! Be careful… ”.

But he was already halfway up the ladder, and turned to press a silencing finger to his lips. “At least let me try.”

Annie laced her fingers behind her backside, half turned her head, and smiled and sighed as if they were a single gesture. But she held her tongue, and Will resumed his climb. Soft morning sunlight from a casement under the eave filled the loft, the air cold enough that Will’s breath steamed in coils. Will cat-footed to bedsteads ranged side by side along the left-hand wall; the wider held a pair of sweetly snoring lumps and the narrower only one. He paused, a few steps away from the children, and breathed their rich, sleeping scent. It made him lightheaded, as if he were breathing in the pale gold winter sunshine, filled up until he inflated, buoyed, floating forward to unearth his son from quilts and comforters and the featherbed covering the rustling straw-filled tick.

Hamnet slept with his thumb in his mouth, knees drawn up, hips tucked forward, body turned fully at the waist so that his opposite shoulder was in contact with the featherbed. Golden eyelashes fluttered against the boy’s rosy cheeks as Will moved to block the square of sunlight dappling his face, dust motes flitting between them like atomies.

Will crouched, dislodging Hamnet’s thumb gently, and with both hands picked up his sleeping son. He flopped the boy’s slack warm arms around his neck and cradled him close. He squatted on the edge of the girls bed, then, and leaned Hamnet’s still-towheaded curls against his shoulder as he tugged the coverlet down. Susanna lay with her arms widespread as if embracing the morning, Judith’s brown head resting on the soft part of her shoulder. The younger girl coiled around a pillow possessively, her braid snaking across her sister’s breast.

Susanna’s eyes flicked open when the light brushed her face, but Judith cuddled closer to her pillow and mumbled. And then Susanna’s hazel eyes went wide, and as Will saw her draw breath to shriek in delight he put his finger to his lips. She choked on it, clapped her hand over her mouth, and giggled. Will pointed to the ladder and to Judith, and Susanna nodded and reached to shake her sister awake.

He actually got Hamnet halfway down to Anne’s stifled laughter before the boy squirmed awake and blinked sleepily through the tangled blond curls. And then Hamnet did squeal, and cling, while the girls laughed over the edge of the loft.

Will propped his feet on the bench before the fire while Susanna showed Judith how to sew the braids of ivy into swags to hang over the windows and the door, and Hamnet stole fallen leaves with which to tease Anne’s calico cat. The cat, fat with winter mousing, purred and flattened her whiskers smugly, but she couldn’t be bothered to extend a claw after the leaves.

Will, watching, covered his mouth and smiled into his sleeve. Still weary with the brutal coach ride, he must have dozed before the fire, because a knock on the door startled him awake.

“That will be your brother Edmund,” Anne said, crossing in a sweep of skirts. “He’s come to take Hamnet to fetch the Yule log”

“Uncle Edmund!” The boy bounced up even as Will dropped his feet on the floor. His youngest brother a mere twice seven years shook snow off his cloak and hefted an axe. “Ready to go out and slog through the snow with the men, puppy Will!”

“Ted.” Will stood, a broad grin stretching his cheeks. “You’ve grown.”

“You re home.” Edmund looked him up and down. He was already almost Will’s height, and his shoulders half filled the doorway.

“Well, get your boots on, then.” Hamnet bounced on his toes. Will looked at Annie. Annie didn’t quite nod, that would have been too much like permission but she smiled.

“Bring more ivy if you find it, or bay,” she said. “Christmas eve supper shall be at your father’s house; the girls and I will meet you. I promised to help cook.”

The sun turned the western horizon to flame-colored taffeta while the three of them, Hamnet, Edmund, and Will, leaned into the traces and sledged an enormous log through ankle-deep snow. Or, in fairness, Will and Edmund sledged. Hamnet ran rings around them, the winter sunlight glimmering on his hair, now a hare, now a hound, now ‘Uncle Edmund, look!’ a lumbering bear.

Edmund looked, and laughed, and Will looked at Edmund and understood, with a moment of bitterness he didn’t deserve, who was raising his son. Will covered the hurt with a player’s smile, and caught Edmund’s eye before he ducked under the traces to chase his bear-cub down the lane, growling like a hound. They floundered through a snowdrift and into a deserted pasturage, Will half a step behind the boy.

“Run, bear cub! The hounds are on you!”

Hamnet turned at bay against a hurdle, and Will drew up.

“I’m Sackerson, the boy growled. The strongest bear in Britain! I’ll eat up any hound that comes after me!”

Will laughed and crouched down, hands spread, watching his boy coil to leap at him. That Hamnet would trust Will to catch him cracked his grin to show his teeth in more than mockery of a hunting dog’s snarl.

“Hounds are smarter than bears.” He gasped as something took him, as if the snowy grass under his feet were yanked like a carpet, and he found himself flat on his back with Hamnet crouched over him, small fists clenched on the neck of his jerkin, roaring triumphantly.

“Lad,” Will coughed. “Off!” Hamnet jumped back, and suddenly Edmund’s hands were on him, the Yule log abandoned in the lane, a worried brother brushing snow from his collar and hair, pulling him to his feet. “What happened?”

“Fell”, Will said, and shoved his right hand into the slit in his jerkin and the pocket beneath so Edmund wouldn’t see it shake. He wouldn’t say more in front of Hamnet, but Edmund’s lips pursed and he kept a hand on Will’s elbow until they were back in the lane, and did the lion’s share of the drawing.

Another half-hour’s labor brought them through the festive streets of Stratford to the front door of Will’s childhood home. Edmund pushed the door open to the parlor where the great bed stood, halloing unnecessarily as the whole family: Joan; her husband, Will; Gilbert; Richard and guests turned with applause.

The rich smell of brawn roasting and bread baking, of mince pie and fruit pie and plum porridge, was almost as sustaining as food itself. There would be no cold pottage in the Shakespeare house tonight.

In the hall, where the hearth roared in readiness for their burden, some of the guests were playing at snapdragon, picking raisins from a bowl of flaming brandy. Will saw one man dressed in almost Puritan severity quench scorched fingers in his mouth.

Will dropped the traces and kicked snow from his boots against the threshold before stepping over onto rushes scattering the blue limestone floor. He and Edmund dragged the log in with Hamnet’s interference. Then Will left it to his brother’s labor, turning away from the precipitous stair on the left and into the hall, with its walls hung in holly and painted cloth. He could hear Hamnet and Edmund untying the Yule log, and he realized suddenly that they’d forgotten the ivy or bay and then his father’s arms were around him, John Shakespeare stumping forward on a bentwood cane and wrapping his oldest son in palsied arms, leaning as much as embracing, clinging to his boy gone to London and mouthing words about Will come home, in velvet and silk taffeta like a fine gentleman. His father’s words were slurred, one running into the other, and Will knew from the stern, proud look on his mother Mary’s face that he was not to remark on it. The cousins close and distant huddled in a room hot with their bodies and the leaping flames of the hearth, among them men and women Will had never seen.

“Bring it in, bring it in,” John Shakespeare said. “The feast is upon us.”

Mary waited for her husband to step back before she came forward and looked up at Will. Her eyes were blue: she had the aristocratic cheekbones and the high brow she’d willed to all her children, the living and the dead. Will saw her noticing the snow and the earth staining his cloak and the knees of his breeches, but she met his eyes and held out a tankard of mulled cider, and only smiled. “Welcome home, Will.”

“Mother,” he said, and took the wine, searching the crowd for Annie and Susanna.

“Judith would be with the younger children. God bless you.” Her kiss was roses and homecoming, and he let it drive the memory of balance lost and a lurch into a snowdrift away.

“How is Father?” An undertone, mumbled around his cider.

“Not much worse,” she said, and shrugged. “And you?”

“My plays have been performed before the Queen,” he answered, as he had imagined himself answering, and accepted her gasp and smile and delighted outcry as his due.

Annie found him before he finished the cider, and drew him through a low timbered archway into the crowded hall by a warm arm around his waist.

“The brawn is almost ready,” she said.

He breathed deep: cloves and crackling and the rich aroma of roasting pork.

“Annie,” he said. “Something happened today.”

“Not to Hamnet?” She crouched by the fire in the big bricked hearth, tucking her skirts in close as she ladled dripping over the roast. She wore neither bumroll nor farthingale, but a broad country skirt under her apron, and Will bit his tongue at the way those skirts draped between her haunches.

Three children, and still I fell,” he said. “I think.”

“Fell?” She set the battered copper ladle aside and stood, turned, frowning. She took his wrists and drew his hands forward, glowering down at them: broad knuckles, long fingers, the last digit of the middle finger on the right one calloused on the inner edge and warped sideways from the pressure of the quill. The right one trembled.

“Oh, Will.”

“Years yet,” he said. “I swear I’ll come home to you.”

“Broken and old so I can nurse thee through thy dotage? What good will you be to me then?” Her voice low, the bitterness hidden under the commonplace tone of wife to husband. “Pray it pass.”

“Hamnet by, Annie, hush you.”

“There’s a priest here tonight,” she said suddenly, interrupting. “For Christ’s birth. After the neighbors leave, there will be a midnight Mass.”

A priest. She meant a Catholic priest. A Catholic Mass. A hanging affair. Will swallowed dryness. “Annie, you must not tell me such things.”

“Will You were raised to it.”

He knew. He met her pale eyes and shook his head, tasting salt and sour like a reminder.

“Anne. Wife. I’m a Queen’s Man now. Do you know what that is?”

She shook her head. “No.”

He drew a stool out from the table and sat, gesturing her to the bench.

“Hast ever seen a Tyburn hanging, Annie?” She blanched.

“No. Not seen, perhaps. But heard.”

“It is as well.” If I have my will, he thought, you never shall see one. Especially mine.“

“I’ll take Judith and Hamnet home after supper,” he said. “You and Susanna may stay.” She did not argue.

Fourscore is but a girl’s age, love is sweet:

My’veins are withered, and my sinews dry,

Why do I think of love now I should die?

CHRISTOPHER MARLOWE, Dido, Queen of Carthage

In the ten days or fortnight it took for Kit to sort out the social order of the low tables, he learned many things that had escaped his notice when he sat by Murchaud’s side. The talk was freer, although his Kit’s presence was greeted with sidelong glances at first. But when Murchaud left court, and Morgan was not seen, and Kit traded his green and violet and silver for the black velvet he truthfully preferred, the conversation flowed more free. Especially as he was seen in the company of the Mebd’s Bard and her Puck, or sitting alone.

He couldn’t bear the silence of his rooms, and spent long hours walking in the beech wood or along the strand, practicing music poorly with Cairbre or reading in the library. Kit had Latin, Greek, fair French, and slight German, yet he found them inadequate to the books and scrolls and stories there.

The lamia Amaranth found him puzzling over books in strange languages, and with her dapple-scaled tail coiled between chair legs and occasionally, unsettlingly, brushing his calf, she set about to teach him the backward writings of Hebrews (which informed Kit of the names of three of the five symbols Baines and his friends had burned into his flesh: mem, he, and lamel) and Mohammadans, and the brush-sketched characters of far Cathay. Although her smile was cool and she would not answer questions about herself, Kit thought she courted him. He permitted it, expecting her purpose to be revealed hesitantly, but before too long. Wrong again: her silence and amusement remained, counterpointed by her flickering tongue.

And so he continued, restless and although often in company alone. His thoughts were clearer now that he had a goal, but the passive means of accomplishing it and his lack of success as bait flustered him. More unsettling, it wasn’t any easier to keep track of the days when he was focused on it. He went so far as to carve notches in a candle, and stopped when he began to realize that the number of notches changed. As his head cleared further, though, the craving in his belly grew. He had to talk to Morgan. Jilted lover or no.

Of course, a jilted lover might be expected to wish to speak to her. If not too often. And I am tired of being treated as a pet.

He frowned, thinking that he would not trust himself with matters of import, as mooncalf as he had been.

Hell, I can ask her about love-in-idleness, too. And why Amaranth said she was cruel.

Kit dressed as Will would have it like a cobbler’s son: a shirt of cambric, a leather jerkin, and brown wool breeches. He slipped the iron bootnail from the pocket of the doublet he had been wearing and was about to drop it into a lacquer box on the stand beside his bed when he hesitated. He could almost fancy the sound of a cobbler’s hammer, familiar from childhood, and smiled for a moment at the memory of his father with a mouth full of tacks just like this one. It might have been the scent of leather, or the way the light caught on the worn surface of the nail, but he suddenly couldn’t bear to set it aside. He slipped it into his purse and let it clink against coins he’d had no occasion to spend.

Here is the palace, and the court. But there is no Faerie city. No tradesman, no farmlands, no ports for ships trading the wide and wandering sea …How strange.And then Kit smiled, because there was a lyric in it.

He stomped into his boots, and left his cloak and his sword behind. Should anyone ask, he was only going for a ramble. How far to Morgan’s cottage, he could not estimate. Murchaud had said through the beech wood, but Kit’s explorations had not found a farther edge. They had taught him that the wood changed from day to day; on one the brook might bend beside an enormous gray boulder like a menhir, caked with moss and lichen; on another it would run straight and tossing over rocks through the spraddled roots of a rogue oak, rough-barked and errant among the smooth-boled beeches, vast enough to build an Ark. Then again, there might be no brook at all, and the wood might sweep up the flanks of rolling hills, spacious and silent and lit like a green cathedral.

Kit followed a graveled trail through the palace’s sprawling gardens. It became a sort of bridle path at the verge of the wood. He paused there for a moment to settle the leather bottle of water on his hip and get his bearings. Then Morgan’s house,he thought, and set his foot upon the path.

Today it was late summer under the trees, the day bright and serene, shade and a light breeze welcome in the morning’s heat. He regretted the jerkin, but knew he’d want it if the sun set while he was in the wood. He didn’t object to sleeping rough and hungry for a night, but he wasn’t overfond of shivering in a pile of leaves until morning. The trail tended east, gladdening Kit’s heart, and it passed over the brook; there was a brook today, brown water dappled by sunshine on a well-maintained footbridge. Kit was wise enough to step off the trail and leave prints down the muddy bank, crouching on gravel to cup water to his mouth. He drank deep to spare what he carried, smiling at the hop and splash of infant frogs the same bronze as the silt.

“Hurm,” croaked the troll under the bridge as Kit hopped to the first of four rocks on the way to the far bank. “Harm.”

“Good morning, Master Troll.” Kit’s hand would have dropped to his swordhilt if he had been wearing one.

“Good morning, Sir Poet.”

“You know me. I know your eyepatch,” the troll answered. “I know your errand.” Its eyes blinked like cloud-filtered moons from the gloom under the bridge sarch. Kit saw a knobbed and swollen nose, slimy skin reflecting the yellow glow of those eyes, and the splayed fingers of one weird hand balancing the thing’s crouch. He couldn’t make out enough of its body to get an idea of its size.

The space under the bridge was darker than it ought to be and there was no silhouette cast against the light on the other side, so he saw only splinters of warty hide, the hump of a shoulder illuminated in the thin bands of sunlight that fell between planks.

“Mine errand?”

“Always on the Queen’s business, aye. One Queen or another.”

Kit didn’t like his footing on the stone, which rocked under his boots. He stepped into the stream, calf-deep, a cold gout of water soaking his leg to the thigh.

“How may I assist you, Master Troll?” From the sound, Kit would say that the troll sucked snaggled teeth as it thought that over.

“Well. Tis a troll bridge, in it? So logic says you have to pay the troll.”

“I went around.”

“That you did, that you did.” The troll coughed, an unpleasant fishy sound. “But you drank my water, and you scared my frogs”

Kit sighed. He was in no mood to haggle, and losing light. “A piece of silver?”

“And what does a troll need with silver, Sir Poet?”

“What does a poet need with a bridge?”

“Useful things, bridges.” The troll brightened. “You can pay me with a song.”

“A song. Mine own?”

“What use is a poet, else?”

“Do you intend to keep it, if I give it you?”

“Keep and pass along,” the troll answered, lowering its glowing eyes and curving its hand as if it studied the cracked yellow pegs of its fingernails. “As anyone might a song. If anyone would listen to a troll sing. But if you mean, will I take it from you no, that’s a price worth more than a fording. And everything in Faerie has a price.”

“I’m learning that.” Kit turned in the water to put his blind side to the bank, which was only marginally less discomforting than facing it to the troll. He might not hear the rustle of leaves over the splash of the brook, if anyone snuck close.

“A love song, or a lament? Or something warlike, I know a few of those.

The troll sighed, and Kit saw his shadowed outline settle on its haunches.

“Harm, hurm. A love song,” he said in a dreaming voice. “There’s little enough of love under bridges.”

“But plenty of frogs.” Kit winced as the words left his mouth. Too clever by half, Master Marley. Or Sir Christofer. Whoever you are today.

“Ah, yes,” the troll answered. “A surfeit of frogs. Froggy frogs, froggyfrogs.” He followed it up with a froggy-sounding laugh; Kit glimpsed something like the white swell of a pouched throat. “Sing me a song, toad and prince.”

“I know the song for you.” Kit drew a breath and steadied it, and didn’t sing so much as chant: ‘Come live with me and be my love’

It was a simple song on the surface, an uncomplicated pastoral, but political on the bottom of it. Who was, after all, the famous shepherd who sheared his flock so close as to dine off golden plates? Reciting it made Kit feel he was getting away with heresy.

The troll listened in silence, his hands with their old-man’s knuckles and old-man’s claws twined one about the other, and he chirruped once or twice in amphibian emotion. A few moments followed with only the wind in the trees and the water over the rocks, and then the troll said, “A right sunlit song.” A sound like ripping cloth followed.

Kit stepped back, feeling his way over slick stones. “You re welcome.”

“No fear, no fear,” croaked the troll. He thrust a hand out from under the bridge, something brightly dripping knotted in the gnarl of it. “For your cloak. For the song.”

Kit hesitated, but the troll stayed motionless, although its yellow-green mottles pinked in the sun. “For my cloak?”

“Can’t be a bard without a cloak,” the troll said, and shook the bit of cloth. “Take it. Take it for your song.”

Kit picked his way forward, following a sand bar scattered with stones. He stopped as far back as he could, and made an arch of his body to reach toward the troll. His hands closed on wet brocade, and the troll jerked its scalded hand out of the sun.

“Hurm, harm. On your way then, bardling. I’ll see you again ere your cloak is complete. And I say that knowing: trolls have the curse of prophecy.” It withdrew under its bridge.

Kit scrambled to the far bank, turned back, and bowed in wet boots once he attained its height. “Rest ye merry, Master Troll.” There was no answer, but he fancied he heard a muted chant taken up in a croaking voice before he was quite out of sight of the bridge.

“Come live with me and be my love, hurm, And we will all the pleasures prove, harm, That valleys, groves, hills, and fields, hurm…”

Three or ten hours later, he was forced to admit he was lost. Or, if not lost for he had never left the bridle trail, or what-you-may-call-it, and thought he glimpsed the spires of the palace once or twice, when the trees grew thin at the top of a rise at the very least he was sorely misplaced. He sat on a mossy trunk and drank water and inhaled the clean musty scent of the forest. The troll’s scrap he spread on his knee to finish drying, and he considered it as he considered his options. With the water wrung out, the brocade was as satiny red as rose petals, woven of some fiber Kit couldn’t identify.

He rested his chin on his hand and scratched idly under his eyepatch, watching the light. What filtered through the widely spaced pewter boles of the beech trees was growing golden, although the breeze was still balmy. He didn’t think he’d find Morgan’s cabin before sunset, and if he slept here, he’d have the fallen trunk and the hollow under it to break the wind. A hungry night, but … crunch …