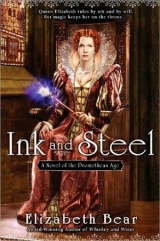

Текст книги "Ink and Steel"

Автор книги: Elizabeth Bear

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 11 (всего у книги 29 страниц)

And then the third voice. Precise, a little pinched. As pompous as his peascod doublets: the voice of Edward de Vere, the Earl of Oxford. Kit covered his face with his forearm, blocking the incessant drip. “Have your men see he stays under control, Master Poley. I’d not waste another playmaker. Though so long as he seems biddable, there should be no danger; lord Burghley relies on me to guide his production, and there have been no incidents such as those that provoked us to deal so harshly with Master Marley.” Kit almost lost his grip on the beam.

“Have you aught else to report? Anything of Thomas Walsingham?” Baines voice, the first part lost under the rumble of the thunder and the vsudden agony of Kit’s throat constricting. You broke it off, Kit. You were young. You learned. You never meant a thing to him. Edward.

“… Thomas Walsingham’s trust is secure. I’ve made evidence that Marley was involved with enemies of the Queen, and Thomas has accepted Master Poley’s judgement. With some tearing of the hair. I gather they were bosom friends.”

Kit straightened his arms against the beam overhead. Cold water dripped onto his forehead and ran down his arms as he let his head loll back. It mingled with slow heat leaking down his cheek, dripped burning against the back of his throat. He tasted salt and didn’t lower a hand to wipe it dry. ‘Edward,’ he mouthed. Oh, unhappy Marley. He’d blamed poor Thomas for his murder all unfairly, and it was fickle Edward all along.

Baines said, “Walsingham suspects nothing, my lord.”

“Excellent. What news from the Continent?”

A band of heavier rain swept the alley, and Kit couldn’t bear in any case to listen longer. The pang that wracked his belly was the final consideration: he couldn’t be sure if it was hunger, or the doom that would drive him back to Faerie, but he didn’t dare stay wedged under the stair. He slung a leg over the crossbrace and locked his ankles around the timber again, thinking, At least going down will be easier than coming up.

Except his hand slipped on slimy wood as he shifted his hip off the crossbrace, and he grabbed wildly for the timber and got a slick handful of rain-soaked bark that peeled free. He wasn’t sure how he remembered not to shout as he skidded two feet, asmear with whitewash and crumbs of wood, that splinter lodged so deeply now he thought he’d die of it, his eyepatch tearing loose a knot of hair as it went into the gulf underneath. His sword stayed blessedly fast in its scabbard, though, and for a long moment Kit hugged the timber and just breathed long, slow rattling breaths that hurt more coming out than going in.

Somehow he made it to the ground and stood against the timber, shaking more with his realization about Oxford than with the terror of the climb. He knew the length of such reports to the minute, and Poley and Baines would be emerging soon. What’s another betrayal? I already knew what he was. At least I’ve confirmation. Edward II stung him. Although perhaps more than I intended.And then a bright flare of hope, quickly doused. It wasn’t Tom. And so what if it wasn’t? The thought that must concern me is whether Edward is our only traitor.

Kit pulled himself away from the timber and bent to retrieve his cloak. He couldn’t find his eyepatch; the rainwater felt odd trickling over the drooping eyelid and the scar on his blind side. But at least with the cloak too sodden to wear, it was unlikely anyone would look past the whitewash daubing his form, the blood and mess and the long-healed wound to recognize a dead man’s profile. He needed Morgan. He needed to get another message to Francis, that his cousin was innocent and Oxford the man not to be trusted. We, We. Kit, there is no we any more. You serve a different Queen.He would have laughed if he’d dared: first the sinking horror of betrayal and then relief that left him giddy. Edward, not Thomas. Why is it so much better to be betrayed by one former lover than another? Because it is better to have a vile impression of someone once cared for reinforced, than to have one’s heart shown irreparably flawed.

He picked his way out into the steadier traffic of the street, too weary and pained to keep to the shadows though passersby were offering his bloody, whitewashed, rain-streaked visage curious stares and wide berths. There was a rain barrel up on bricks a half block further on, and he thought he might wash his face. Kit kept his eye on his shoes, cautious of the slick cobbles. He wouldn’t have looked up at all if a hurrying figure hadn’t drawn back a startled step and gasped.

“M Marley? God’s blood.”

Kit looked into the eyes of a narrow little man with a narrow little face. He was well dressed and well wrapped against the rain, and he skittered back three steps and bared his teeth like a trapped rat as Kit advanced, reaching across his body for the rapier.

“Nicholas Skeres,” Kit muttered between the draggled locks of his hair. He tasted lime and blood and soot, and spit them out upon the road. “Thou murdering bastard. I’ll see thee hang.”

Skeres eyes widened so the white showed in a ring. He gave a scream like a startled girl and shuffled backward, tripped on a stone, and sat down hard in the slops.

“Kit, stay thy hand.””

“As thou didst stay Ingrim s?” Another step forward, the naked blade in Kit’s hand pointed at Skeres left eye, only a few short steps distant. The damage is done. You’re recognized. You may as well get the pleasure of his blood

Passersby were halting, drawing back, staring and muttering.

“Tis Master Marley’s ghost.” A woman’s shocked voice: one he knew not, but he’d been well enough known. The murdered playmaker. From some window open to the rain, a drift of music followed. Kit turned his head to regard the semicircle ranged on his blind side.

A half-dozen men and women huddled in the rain, frozen with fear or fascination. He ran a cold eye over them and they drew back. He was all over whitewash and blood, and he knew what they must see: a tattered figure smeared with the lime of the grave, the blood of his fatal wound rolling from the socket of his missing eye, leveling a naked blade at a sobbing killer.

It was too much for a player’s imagination. And a few reports of a dramatic revenant wouldn’t risk the sort of intelligent questions that a dead man returning from the grave to slaughter his own murderer might. Skeres claiming a visit from Kit’s ghost could be drunken fancy. Or Hell a ghost, for all that. Kit had been careless and greedy, and he wouldn’t have Will or Francis or a true innocent like Burghley’s changeling cousin Bull caught in the net of that carelessness. Kit smiled through the blood and tilted his head to look his prey in the eye.

You’ll die screaming, Nick Skeres, he whispered. The man flinched down into the gutter, a fresh reek of urine hanging on the rain-wet air, and Kit whirled on the ball of his foot. Silent in his nail-less boots, carrying his naked blade, he ran into the storm and made himself gone.

Pedro:

I shall see thee ere I die, look pale with love.

Benedick:

With anger, with sickness, or with hunger, my lord,

not with love: prove that ever ILoose more blood

with love then I will get again with drinking, pick

out mineeyes with a Ballad-maker’s pen, and hang me

up at the door of a brothel housefor the sign of

blind Cupid.

WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE, Much Ado About Nothing”

“Thou didst send for me, and I am here.”

Annie lay on his bed, her shoes lined side by side beneath it, her hair unpinned and spread like a river on his pillow, spilling over the hand and arm she propped her head upon. “I stink with travel, Will. Wouldst call up water?”

Will, fussing with the lamp, smiled. Her terseness had the welcome sound of home.

“I’m glad thou didst come.” He stepped out the door and down the stairs, found the landlord’s ten-year-old boy, Jack, dozing in the common room.

“Warm water for my wife.” Will dropped half a silver penny on Jack’s lap. “And see if there’s any of the pig left.” He’s only a little older than Hamnet.

Jack vanished into the kitchen so fast he blurred. Will clumped back up the stairs, dizzy with the effects of a long day’s work in the heat. “Water is imminent. And thy supper, too, if thou likst. How are Hamnet and the girls?”

“Growing. Susanna’s tall as a willow. They’re with thy sister Joan. Come home, Will.”

He left the door unlatched and plumped down on the boards beside the bed in the flickering lamplight, the window thrown open despite the stench and sound of the streets. “Thou knowst I can’t.” He reached up without looking, caught her skirts, and tugged until her legs slid over the edge of the bed and her feet dropped into his lap. “I’m good at this, Annie. And …” The door swung open at John’s tap. Will moved Anne’s legs aside and rose to relieve the boy of his bucket and the cold pork and bread. Will latched the door and set the food on the table, shoulders aching as he hefted the bucket.

Anne peeled her stocking down, her leg raised in the air, her skirts in disarray and a wanton gleam in her eye. “Wash my feet for me, Will.” Her bare foot ran up his calf, tickling the back of his knee.

“Annie.” He set the bucket down and sat on the bed beside her, a careful six inches away. “Dost want thy supper?”

“Tis not supper I’m hungry for.” She curled against his back, pressing her soft bosom against his shoulder, her hair across his shoulder like a veil. She smelled of dust and travel, of sweat and great distances, and of sachet lavender.

“I won’t risk thy life for another babe, Annie.”

“Tis not a babe I crave, sweet William. I’m too old to catch.”

“Oh, Annie.” He turned and put his hands through her hair, and closed her eyes with a kiss. “Not so old as that, I warrant. They say a love match never comes out well, but after all I went to winning thee, Wife, would I risk thee? Another birth like the twins would finish thee, and thou wert younger then.”

“It wasn’t so bad.”

“There was blood through the ticking, Anne.”

“There’s someone else.” Flatly, a dead inflection that squeezed his heart like a fist.

“A player’s dalliances. No one who matters. A husband’s prerogative, in the absence of his wife.”

She tugged her skirts out from under his leg and squatted beside the bucket, unlacing her bodice and pushing aside her smock as if the bitterness in her voice were the tones of idle conversation. He watched her wash her arms and neck, the shadows under the well-nursed softness of her breasts. The lamplight streaked her hair with an unfair quantity of gray.

“I’m well provided for. Where does the money come from, Will?”

“I’m in favor at the court. And living over a tavern.” He looked around the Spartan room, seeing it through her eyes. “I’m not here often,” he said at last. “I should see to better lodging.”

“Thou canst write plays in Stratford. Thou canst see thy children grow. I’ll content myself with stable-hands.

He turned to her, startled, and saw her rock back on her heels and smile. “If a husband may seek comfort elsewhere, Husband Mouse.”

“Thou wouldst not.” She sighed and stood, her hands linked palm to palm before her thighs. “If thou’lt not risk me, should I risk myself? I die of idleness, Will.”

“Three children and a cottage are not enough housewifery for thee?”

She kilted her skirts up, standing first on one leg and then the other to wash the grime from her feet. Will watched her toes flex, the arch of each foot grip the floor. “I’ll clean my hair tomorrow,” she decided, and stepped around the bucket, leaving footprints like jewels on the boards. Her hands on her hips again, challenging, and the curve of her clever neck. Not so different than she’d been when they’d conspired to marry over family objections, all those years ago.

He coughed into his hand. “If thou wilt not tumble me,” she said as she came to him, “wilt at least come to thy bed and comfort me with thine arms?” He blew out the lamp and did as she asked, and pretended not to hear her weep.

Until the small hours, when the noise from the street below grew slighter and she moved against him, mumbling into the dark. “I want a business, Will. If thou hast playmaking, then give me something other than stitchery and child-chasing to fill the hours.”

“What wouldst thou?” He felt her smile against his shoulder, and knew he was lost.

My lord husband. I could make thee a wealthy man. A long pause, and shimmering wryness. I want to buy land.

Which she could do only in his name and person.

“With the income I send?”

“And mine own portion.” Her held breath stilled against his cheek, he considered.

“Annie,” he said, and still heard no hiss of breath through her lips. “Send me what needst my mark,” he said.

“Mean old biddy. Stripling,” she answered, and kissed his cheek above the beard, and he was sorry that was all.

Can kingly lions fawn on creeping Ants?

CHRISTOPHER MARLOWE, Edward II

“Sweet Kit.” Murchaud shook his head, black curls uncoiling across the silver-shot gray silk taffeta of his doublet. He reclined beside the fire, an octavo volume propped on his knee. Kit looked up from the papers spread on his worktable and smiled through the candlelight, wary at Murchaud’s tone.

“You must not weary yourself on the affairs of mortals, my love. It will bring sorrow.”

Kit blotted his quill and laid it across the pen rest. Methodically, he sanded black words, setting the letter aside unfolded when he stood. “A command, Your Highness?”

Murchaud set his book aside and stretched on the divan, gesturing Kit closer, but Kit stood his ground.

“Nay, my lord.”

“Kit.”

“Nay, my lord.” He scraped a bootheel across the flags and frowned, turning to look into the flames of the cross-bricked hearth.

“Where has Morgan been?”

“What mean you?”

“I mean,” Kit said, watching ash crumble at the edges of a cave among the embers that glowed cherry red as a dragon’s eye, “she has not summoned me in … How long has it been?” He shrugged, running his tongue across the cleft in his upper lip and then frowning as he nibbled his mustache. “—some time.”

Kit heard the Elf-knight stand, his almost-silent footsteps as he closed the distance on Kit’s blind side.

“She has a cottage where she flees the court. It lies behind yonder beech wood. I will see that she knows of your sorrow. There’s worse to come.”

“What mean you?” The hesitation was long enough for Kit’s gut to clench.

“I’m leaving in five days. The Mebd sends me on diplomacy.”

“Where?”

“I cannot say. But it will be hard for you; Morgan must keep her distance now, and you must seem alone while I am gone. It must seem she has tired of you. You’ve played this game before. She said she warned you.”

Kit looked up. “That I might be needed for skills beyond poetry. Am I naught but a Queen’s toy, Murchaud?”

The Elf-knight smiled. “Is that so terrible a thing to be? You courted Papists for your former Mistress. There are factions in Faerie that are not so fond of your new one, or the Queen. You’ll be attractive to them.”

“The ugliness of the intelligencer’s lot,” Kit said. “Win a man’s trust. Become his friend. Whisper words of love in his ear as you slip in the knife. Catholicism is as excellent a religion as any, I suppose, so I have no reason to prefer Protestants to Catholics. Nor this Fae to that Fae, Murchaud.”

“No,” Murchaud answered, a gentle hand on his elbow. “But thou didst serve a Queen those Papists would have seen murdered, didst not?”

Kit turned back to the fire. “I did.”

Murchaud bent close amid a scent of new-mown grass. “And now you serve another, whose enemies are also manifold. Shall you serve her less well?”

“That other service, for all its blackness, I chose.” Kit sighed and nodded, and Murchaud draped an arm around his shoulders. The Prince’s tone grew intimate.

“You mourn your other life? You miss smoky, brutal London and its pox-riddled stews, its painted Ganymedes, and its starving pickpockets, soon to be hanged?”

“Should I not?”

“Ah, Kit.” Warmth, yes, and pity. “You’ll outlive it. Outlive all your loves and hates. Tis easier to lose it now, all of a piece, than by shreds and tatters.”

“… outlive it?” He turned and looked, despite himself, and caught Murchaud’s expression as the Elf-knight reached to steady him. “Outlive the mortal world?”

“Faerie does not move as the iron world, and you’ll not age here. How long did you think you had lingered here?” Earnest eyes, and dark brows drawn together.

“Hast been a year and more in England, two, three summers here.” Kit swallowed. His voice trailed off at the smile in Murchaud’s eyes. “How long?”

“We mark by the tithe,” Murchaud answered. “The teind we pay to Hell for their protection. Every seven year we draw lots, or a criminal may be chosen to go, or a changeling stolen or, rarely, someone will volunteer. Which last pays the debt not for seven years, but for seven times seven.” He shook his head. “Tribute to our overlords.”

Kit shivered. Murchaud hadn’t answered the question. Kit tried to think back, to count summers and winters, flowerings and fallings. He looked down at his right hand, turned it to examine the tendons strung across the back, the calluses ridging his palm. How long? He had no answer. “When’s the tithe, then?”

“Hallow’s eve. Always.” Murchaud shook his head.

“Hallows eve here or in the mortal world?”

“Time here is an illusion,” Murchaud answered. “In the mortal world: Hallow’s eve, fifteen ninety-eight.”

“Four years hence.”

“Not so very long. Do not pine so for your lost life, Sir Kit. Set it aside, and do what you can to make yourself a stronger place in this court.”

“You suggest I could be sent, if the Mebd does not value me? Although your mother claimed my service? Kit Marley in Hell it has a certain symmetry.”

“The Mebd values you,” Murchaud said. “But she trusts her sister, my mother, not at all. Wert wise to make as many friends in court here as thou couldst, and let thine old friends glide past. The river of time will bear them to their end more quickly than you imagine.”

“I,” Kit swallowed. “Soon enough, then, I shall be beyond that. Had I no loyalty, what would I be worth to you?”

“So be it,” Murchaud said. “Bloody thyself on the bars of thy cage, but know thou canst not straddle the flood between that world and this forever.”

“I did not choose this world.”

“No. This world chose you. Live in it, or it will cut you deep, my love. You cannot go home again.”

“Have I leave to help my friends?”

“I will not forbid it,” Murchaud answered. “But by the love you bear me, pay more mind to courting your Queen.”

Kit nodded, watching the flames. He didn’t tell me how long I’ve been here. How much time could I have lost?The answer brought cold sinking in his belly. In a Faerie Court, Marley? You could lose your whole life in a night.He frowned, and didn’t think of the letter to Walsingham on his desk, with its icy, alien words about Edward de Vere. “As you wish.” He turned his back on the fire and walked to the cupboard, taking his time in selecting his clothes.

“Where are you going?” Kit looked up, fingers stilling on the ruched sleeve of a padded doublet. He turned over his shoulder, enough to see Murchaud clearly. “I must dress if I am to dine with the Queen.”

“Sit at the low table,” Murchaud told him. “We shall pretend at a falling out. I cannot come to you tonight. Or any night until I return from my travel.”

“How long?” But then the Elf-knight kissed him, long hands cradling Kit’s face as if he cupped a rose in his palms, and Kit forgot to pursue the question, after. If after had any meaning here, at all.

Morgan’s rooms, on the third level of the palace, opened onto the gallery over the glass-roofed Great Hall. Murchaud’s were a level lower, in a side hall near the Mebd’s chambers. But Kit’s chamber was in the east wing, and to come to the main level he descended a spiral stair rather than the Great Stair, as he had on his first night. From there, he passed through a corridor to the atrium in all its tapestried magnificence. He drew up before towering ebony doors. Knights in armor, as unmoving as suits on stands, guarded the portal on either side. He ignored them for a moment and studied the dark, coffered carving: intricate spirals and knotworks, fancifully interleaved. And what is it you’ve been seeking these past seasons? A melancholy existence in exile? How … romantic.

Murchaud had threaded the stem of a pansy through the pearl-sewn embroidery on Kit’s doublet; its golden-eyed, plum-colored face nodded against the mallard’s-head green of the velvet, the color Murchaud had insisted he wear.

‘No knight should do battle without a favor from his lover. Green and violet are the Mebd’s colors,’ he had said. ‘If ever you learned to court it in the mortal realm, use that now, and know you walk a line even finer than mine own.’

Kit licked his lips into a smile for the bravado of it and stepped forward. The doors swung open smoothly, and he entered the great, galleried hall with its thousand torches burning with a golden, unholy light.

The room was silent but for the faint, plucked twang of an untuned string: the bard Cairbre straightened over his lute and looked up at the swing of the door. He was alone in the Great Hall. Kit was early. So much for bravado. He laughed at himself and walked between the parallel trestles stretching the length of the hall. No fires burned at the hearths, and the high table sat on its dais swathed in silk that picked up the damasked colors of the marble tiles under Kit’s boots.

“Good even, Master Harper.”

“And to you, Sir Christofer.” The bard made as if to stand, reaching out to set his instrument aside, and Kit gestured him back onto his stool. “Come out of your self-exile after all?”

“There’s only so long a man can take to his bed.”

Cairbre’s eyes flickered to his breast: the blossom?– and the bard frowned. “As you say. Will you grace us with a poem tonight?”

It wasn’t a question Kit knew how to answer. He folded his right arm over his left and shrugged, silent until Cairbre took pity and tilted his chin to indicate the little stage, its assortment of harpsichord, gitar, lute, and archaic-looking instruments that Kit barely recognized. “Do you play?”

“Viola a little, though I am sadly out of practice.”

“Every gentleman should know an instrument.” Cairbre did stand then, his patch-worked cloak of multicolored tatters falling about him as he bent to pull a cased instrument from a cloth-draped stand. The bells on his epaulets rang sweetly as he laid it on the stool.

“I have a viola here.” He chuckled, and indicated Kit’s boutonniere with a flick of his fingers. “To match the one at your breast.”

Kit laughed. “I’d only embarrass myself.”

“Nonsense.” Cairbre’s calloused thumbs stroked the clasps on the leather case, expertly flicking them open.

“After the masque you gave us for Beltane Masques.”

“Silly things. What’s that to do with music?”

Cairbre shrugged broad shoulders, tucking a strand of hair behind an ear, pointed like a leaf. His merry eyes fixed on Kit’s face, and he smiled through a tidy black beard.

“What has anything to do with music? We fools and poets must hang together, ah, Master Puck! Speak of the Devil.”

Kit turned. Robin Goodfellow ducked under the high table and hopped down from the dais, twirling a bauble in time to the bobbing of his ears.

“Devils for dinner? Not tonight, but mayhap on another. Do you like yours roasted, or baked?”

“My devils, or my soul?”

“Why, Sit Kit,” the Puck said. “Do you have a soul? I’d think you half fey already, and as soul-less as any of us.”

“Soulless?” Kit glanced over his shoulder at Cairbre, who opened the case and slowly folded back the layers of velvet and silk swaddling the viola.

“Soulless, aye,” he answered, unconcerned. “As all Fae are. Tis the source of our power: Heaven has no hold over us, and Hell only the power we grant it. Our immortality is of the flesh. While your sort,” a dismissive gesture,” bloody yourselves over who has the right to interpret the will of that one, and worry at his will, choosing those who govern you.” A curt gesture of his chin upward; Fae, he couldn’t say the Name.

If Heaven has no hold on you, why do you fear God’s name?

Instead, Kit said: “And who governs you?”

“Those that can. Go ahead and pick it up, Sir Christofer.” Cairbre stepped away from the case, swinging his tattered cloak over his arm.

Kit stroked the cherry-dark neck. “I’m really not …” But his fingers slipped around the wood and lifted the beautiful instrument from its crimson bed. The varnish glowed in the torchlight, a rich auburn, a master would have despaired of capturing in oils. “I’ve never touched something like that,” he breathed, as if it were alive in his hands and might spread wings and spiral up into the vast galleried chamber, lost.

“It should be in tune.”

Kit looked from Cairbre to Robin whose ears waggled in amusement and raised an eyebrow, but he took the rosined bow when Cairbre held it out, inhaling the dusty-sweet pine scent until he fought a sneeze. He closed his eye, settled the viola, raised the bow and fluffed the third note.

“I warned you. Lessons,” Cairbre decided, and took the bow away. “Come. You’ll give us a poem tonight, won’t you?”

“Yes, Kit answered. I’ll give you a poem.”

He expected they’d wait for Murchaud’s departure, whoever they might be, but perhaps not too much longer. But that first night, as he sat sharing a trencher with Robin Goodfellow below the cloth of estate, he was bemused by the strangeness that filled him. In another setting he might have called the feeling fey: back to what I was, when I was little more than a boy and full of myself and my secrets.

Puck sat at Kit’s right, on his blind side, and saw he ate, though his appetite forsook him in Murchaud’s absence. Halfway through the meal, Kit realized the little elf had deserted his own place at the high table to stay with him. Kit imagined he looked strange as a swan among magpies beside the lesser Fae.

The Daoine Sidhe the Tuatha de Danaan as they were called claimed descent of the Old Gods of hill and dale, of moor and copse and ocean. A Church scholar might have said the blood in their veins was that of demons, not deities. Kit had long past given up his illusions that God kept his house in a church. Their sea-changing eyes and leaf-tipped ears marked them as something other than human, and their wincing aversion to the Name of the Divine might be evidence. But then, what god would abide the Name of his supplanter?

But they did, in broad, look human. The elder, stranger Fae did not. Though they sometimes dined at the Mebd stable, served delicacies by brownies and sprites, and though many of them served in her palace, they were not Tuatha de Danaan, not Daoine Sidhe. And they were as strange now as ever they had been on Kit’s first lonely walk into the throne room that lurked behind the second closed pair of doors.

Across the table rested a lovely maid-in-waiting whose forked tongue brushed the scent from each morsel she tasted before she lifted it to her mouth. On his left, a creature more wizened than even Robin crouched on the edge of the table and ate between his knees.

Kit stifled a chuckle, thinking what his own mother would have said about boots on the table, and turned to murmur something in Robin’s ear. A polite hiss from the scaly young lady across the table interrupted.

“Sir Christofer?” Thread-fine snakes writhed like windblown curls about her temples. Her eyes were as flat and reflective as steel, the pupils horizontal bars.

“Mistress Amaranth.”

It might have been a smile. Her lips were red and full, a cupid’s bow disturbing behind the glitter of scales like powdered gold rubbed on her skin. Her hand darted with a swiftness that should not have surprised him, brushing the flower on his doublet before he could jerk back.

“Does it not shame you to wear the love-in-idleness?”

“There is more here than I understand.” Remembering Cairbre’s comment, and how Morgan and Murchaud had both adorned him with the blossoms. “Love-in-idleness?”

“Heartsease,” she said, while Puck pretended not to hear. “The pansy or viola.”

He pulled his bread apart in tidbits, setting the balance of it beside the trencher while he buttered a morsel, covering his confusion with concentration on the knife. It seemed dry as paste; he would never have choked it down without wine.

“It pleases my lady, Mistress Amaranth.”

The lamia’s hair hissed again. He thought it was a chuckle.

“Then she is cruel, is she? I am not surprised at that.”

“Not so cruel as that.”

“Cruel enough,” she said, gesturing for a footman to lay a bloody slice of roast upon her plate.

“Kind as any woman,” he answered.

Amaranth’s cold eyes widened; the Puck snorted. Kit toasted Amaranth, wondering what moved him to defend Morgan for all her late absence from the hall, and his bed. But his gaze traveled past the serpent, up to the dais and to Murchaud sitting near Cairbre, at what would have been the Mebd’s right hand if the Mebd were there. Even across that distance, the look Murchaud returned pressed Kit back as physically as a thumb in the notch of his collarbone. He reached for his wine, feeling as if he choked.

And now I truly am alone. Until he returns. Or until Morgan claims me. In deep deception, and in the hands of the enemy.

He held the Elf-knight’s withering glance until it seemed the whole room must have noticed. Until conversation flagged around him and Amaranth herself turned to follow the course of his one-eyed stare, then leaned aside as if she would not break the strung tension. Murchaud looked down first, turning to laugh nastily at some comment whispered by the Mebd’s advisor, stag-horned old Peaseblossom. Kit watched a moment longer, then dropped his eye to his dinner and haggled off a bit of roast as if he could bear to put it in his mouth.

“What’s love-in-idleness?” Kit murmured, bringing his lips close to Puck’s twitching ear.

“What you wear on your bosom,” the Puck answered dryly. “That thing on your sleeve is your heart.”