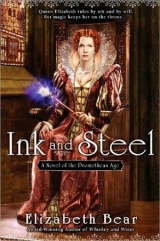

Текст книги "Ink and Steel"

Автор книги: Elizabeth Bear

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 17 (всего у книги 29 страниц)

“Aye,” Poley said, and sheathed his dagger again. “Nearly of an age with you and Kit Marley, as I recall.”

Will neither stood nor looked up as Poley moved toward the door; nor did he finish his ale. He sat for some time in silence, and then he picked that poor shaved shilling up with his fingertips and rolled it twice across their backs as Tarleton had shown him, almost a decade before and made it vanish into his sleeve.

“Well, he said under his breath, that was interesting. Bill.” The last louder, so the landlord looked up. “Will?”

“Is John the carriageman still in residence?”

“Not in at the moment, but he did say he’d be staying as long as you did.”

“Send me a tally,” Will said. He stood. “Let him know I’ll be a week or so here, and then back to Kent. “If he needs to attend his master I’ll find other transportation. I shall.”

“For home already? It’s barely noon.”

“For home,” Will said, and went.

Rome if thou take delight in impious war,

First conquer all the earth, then turn thy force

Against thy self: as yet thou wants not foes.

M. ANNAEUS LUCANUS, Pharsalia, First Book (translated Christopher Marlowe)

It begins in a confessional at nightfall. The subtle bitterness of myrrh, the richness of frankincense, the sweat of the penitent lingering in age-calmed wood. Kit bows his head, leans close to the grille. Above the frankincense, the perfumed soap of the Spanish priest on the other side. With the cloying scent came cloying fear, knotting his belly like hunger, although he is successful. Accepted. Soon, he will be going home.

Christ, not this one. Not this

Kit heard his own voice, latin, the words of ritual. He fixes his eyes before him. Tis a good ritual. Comforting.

“Bless me, Father, for I have sinned.”

“Indeed, my child, you have. But fear not. Your penitence will be adequate before Heaven.”

English, and a voice he knows. Blurs, a jumble of unclarity, of time slowed beyond time. The door of the confessional slides open, Kit blinking in the light as he moves to stand. Each heartbeat distinct as enormous hands close on his wrists, implacable as iron manacles, haul him up; he tries to kick

Kit: slender, not tall, barely bearded, without yet a grown man’s shoulders. He might break nine stone after a hearty supper. Richard Baines simply lifts him off his feet like an ill-tempered child, like a spitting virago, veins bulging in Baines muscle-ribboned forearms as the black robes fall back. Baines bounces him, once, and nausea fills Kit’s throat as his shoulder rips inside like twisted cloth snagging on thorns.

“There’s our cat, Fray Xalbador. Oh, don’t like that much, do you, puss? Got your claws now.” Baines shakes Kit; white flashes occlude Kit’s vision. Hands fumble his belt as the Spaniard claims his dagger.

“Where shall we have him, Fray?”

The priest’s accented voice. “The basement, I think. Tis pity my tools are not here.”

Baines answers, “Mine are.” Baines iron rings pinch Kit’s flesh. The skin at his wrist breaks; blood trickles. He fights, but the other Kit, who watched him, already knowing that Kit curled tight and hugged himself in resignation. Wake up. Wake up. Wake up.

“I’ll see him settled, wildcat!” another bounce, with a kind of a twist to it, and this time Kit screams as his shoulder pops with a sound like a drawn cork, “well, that should make him easier to manage.”

“Broken?”

“Just slipped, I think. Fetch the others, Fray Xalbador.”

This Kit chokes on pain, keening the agony as Baines twists his dislocated arm behind his back to make him march This Kit thinks “Others. This is the core. These are the names Sir Francis needs. ALL I have to do is talk my way out of this. ALL I have to do is live through this.”

That Kit wept for his own innocence. He blinked, and this Kit closes his eyes in pain and opens his eyes in pain, in a room prepared with a half-dozen torches, two braziers, and a fireplace for warmth. Dark, clean, the floor of rammed earth and the walls of mortared stone. Long tables against the walls, and Kit sees chalk, a small heap of candles, twine, and some things he can’t identify as Baines shoves him to his knees and twists his left arm behind him. He opens his mouth to argue, and Baines bends the arm higher. Not much, an inch.

Kit wheezes with pain and locks his tongue behind his teeth. And then there are men in the room, and he can’t beg if he wants to, because spiked iron fills his mouth. He did know the names of four of the other five. Easton, Carter, Saunders, Silver. The last one is a slender-hipped, broad-shouldered blond, barely a man in years, whom Kit would have eyed with some appreciation under other circumstances. Catesby, Fray Xalbador calls him, and Baines calls him Robin.

Easton, Carter, Saunders, Silver. Catesby. Richard Baines. Xalbador de Parma. Easton, Carter, Saunders, Silver I can remember that.

In the dream, the rough iron of the bridle already wears at his cheeks and nose. In the dream, the ruin of his right eye weeps blood and matter down his face. In the dream he kneels quietly at Baines feet, domesticated. ‘And rough jades mouths with stubborn bits are torn …’ History had been different, but dreams were what they were. Puke with that thing in your mouth, Kit, and you’ll die of it.

Kit strains to overhear the quiet discussion without attracting Baines attention. The Spaniard seems to be instructing the others with careful hand gestures. Kit presses at the gag in his mouth experimentally with his tongue, moans as fresh blood flows. Baines catches the iron straps around Kit’s skull in a free hand and gives it a little shake, playfully rattling the scold’s bridle, bruising Kit’s cheeks and tearing at his mouth. Baines reaches through the bars and smoothes Kit’s hair, leans down and whispers ‘Holla, ye pampered Jades of Asia, / What, can ye draw but twenty miles a day?’

Catesby, the splendid blond, turns from the rest and crosses to Baines, looking down at Kit with something like dismay. He’s a bit unprepossessing. Baines laughs, petting.

“He’s a poet. One of their sorcerer-playmakers, a darling of Walsingham’s. Already known around Cambridge for his filthy translations of Ovid, and London for a bloody travesty of a pagan play. Aren’t you, puss?” Another little shake, a caress, and more blood. This Kit nods, biding his time, a chip of tooth working into his gum.

“Good puss. Pick of the litter. It’s distasteful.”

“Twill break their black arts.” Baines jerks his head at Fray Xalbador. “Between me and he, you’ve two priests who say it. Desperate times.”

Catesby smiles bitterly, as that Kit thought but you weren’t there. It was only the five of them. Panic. I would remember if it had been six. I would remember. This is not how it happened. Catesby had been at Rheims, arriving just as Kit took his leave forever.Kit remembered the worn sword, the good clothes, the expansive grin. But Catesby had not, could not have been in that close basement room.

He still speaks. “It doesn’t sit well. But, to the glory of God and the Holy Mother Church.”

“To the glory of God,” Baines answers. Kit doesn’t think Catesby feels the lie in the big man’s words, but Kit does. Feels it in the way his hand tightens on Kit’s tattered arm.

Does Will know how much I left from that I told him?

Which will it be, the pentangle or the circle of Solomon?

Oh, God. No. Marley, I conjure thee, awake.

The braziers smoke as they make him ready, twisted rodstock heating in each one. It’s copies of the poker with which he’d threatened Will, not the irons de Parma actually used, and I fought. I fought and they had to drag me, he goes docile and willing to Baines command. It would be easier if they would bend him over the table, like Edward, so he can’t see their faces. But they want him on his back.

That Kit remembered how he had turned his head, cursing, pulling against the agony of Baines hands, and sunk his teeth in the base of the big man’s thumb. This Kit tries, but the weight of his head presses the bands of the bridle forward, drags the barbs on the bit across the soft ridges on the roof of his mouth in a mockery of a lover’s kiss. Still, that Kit remembered the taste of Baines blood with bitter triumph, and Baines mockery as he inserted the bit.

“Now, puss, if thou’rt going to bite we’ll have to muzzle thee sooner instead of later.”

“A fair idea,” the Spaniard had answered, “to stop his pagan poetry in his mouth. It’s why I had it with my mage-tools. That and in case we laid hands on a fay after all.”

Disorientation, time out of joint. Baines, laughing at the wound on his hand as the Inquisitor fetched the bridle. “Jesu Christi, she even fights like a wench.”

They come one by one into the circle and de Parma seals them one by one within. They take turns, every expression etched on Kit like the scars on his breast, his belly, his thigh. Catesby dispassionate, Silver mocking, Easton with closed eyes and a bitten lip except in the dream, it’s Edward de Vere who rapes him, and sweet Tom Walsingham, and over them falls the shadow of vast, bright wings. He feels the power they filter through him, the cool edgy blade of a magery so different from his own visceral poetry that he has no name for it. As different as blood-tempered, cross-hilted steel is to a crown wrought of raw reddish gold and fistfuls of the gaudy jewels of Asia. And through it all, Richard Baines, hands as sure as irons pressing him to the table, a soft voice in his ear encouraging him, making a mockery of comfort, calling him kitten and puss as it bids him be brave, good puss, it will all be over soon. And he cannot even scream.

God, enough.

God didn’t seem to be listening. Again.

Consummatum est

When they release him he rolls to the floor and lies there, drools blood as fast as it fills his mouth, mumbles through the agony, amazed his tongue will shape words at all. His knees curve to his belly. His chin curves to his chest. The bloody earth of the floor clings to his bloody flank.

“You’re for the Queen’s destruction,” he rasps. The priest nods, unafraid of him. Unsurprising: Kit couldn’t stand if the roof were on fire. “We are.”

“Let me help.”

“You hate her so much? I’m not inclined to trust you right now, poet. But you’ve earned a quick garroting; I’m not an unreasonable man.”

“Was not…” He spits again, smearing at his bloody mouth with a bloodier hand. “Was not Job tested in his faith?” The priest watches, unimpressed. Kit rolls prone, whimpering as his left arm touches the floor. He shoves himself upright with his right, drags forward, more on his belly than his knees. He slumps down on the chill earth and kisses the man’s boot with his broken mouth.

“I beg you. Let me help.” It isn’t enough, and he knows it. He closes his eyes. Both of them.

“If we have a chance to complete the wreaking in London,” Baines says, over the sound of the well-pump he works to wash his hands, “it would help to use the same vessel. Even more if he were willing, of course. Although mayhap our little catamite liked it, considering his tastes. Did you like it, puss?” He crouches beside Kit almost congenially, and tousles the poet’s blood-mattedhair with clean, wet fingers. A look passes between Baines and de Parma that Kit does not understand, does not wish to understand.

De Parma turns away. “Then let him live.”

This Kit covers his face with the hand he can move, curling like an inchworm at the touch, and that Kit finally managed to wake, whimpering, clinging to a pillow wet with sweat and red with the blood from his bitten tongue.

“God in Hell,” he said under his breath, checking guiltily through the darkness to be sure Murchaud still slept.

Kit rolled against the Prince-consort and buried his face in Murchaud’s hair until his gorge settled and his heartbeat slowed.

A nightmare. Nothing but Queen Mab running her chariot over your neck. He’d lived. And three weeks later he had stood in front of Sir Francis Walsingham, his arm still useless in a sling, and reported that the Queen’s enemies were resorting to sorcery and had fully infiltrated Essex’s service. And that he, Kit, had engineered a connection to one of them and the guise of a double agent. He’d worked shoulder to shoulder with Baines, ostensibly as a turncoat on the Walsinghams like Baines himself until 1592, in Flushing, where he had somehow slipped and given away the game and Baines had nearly gotten him hanged for counterfeiting. The only thing that had kept him sane those five years was the knowledge that one day he would look Richard Baines in the eye as a hangman slipped a noose around his neck. And the determination that nothing, nothing that had happened at Rheims would change Kit Marley. And what a fabulous lie that was, sweet Christofer. Because he had walked away from his chance at Baines in London, so terrified of the man he couldn’t have looked him in the eye if it meant his salvation.

Murchaud smelled of clean sweat and violets. Kit lay against him in the darkness and tried without success to chase the reek of frankincense from his lungs.

O absence! what a torment wouldst thou prove …

WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE, Sonnet 39

October, 1597

I should have burned this letter. I should write no more. I know now I’m writing not to thee, but to myself. Still I imagine I might see thee again. But I am a poet, & poets are liars, as Ben Jonson—you would have hated Ben, sweet Kit—reminded me over supper at the Mermaid yesterday. Still, I’ve managed to hold my peace a year. Perhaps I am learning independence after all. That was what sent thee back to Faerie so hastily, wasn’t it, my friend? The worry that Tom & I wouldn’t stand alone. Thou wert probably right. There is the usual news, fair & foul. Mary & Robin are well. Robin tall as a weed, & Mary we’ve found work as a seamstress with the lord Chamberlain’s Men. We’re the lord Chamberlain’s Men again, George Carey lord Hunsdon has taken his father’s old place in the wake of Cobham’s death, God rest his eternal soul, merrily, & in a place where entertainments are shown daily, much may it chafe him. Oh, Kit, the litany of the dead grows long. The gossip might as well grow on trees. Gabriel Spencer, who I mentioned when I wrote you last, killed a man in a duel before Christmas. And he and Ben Jonson were arrested in July. Ben says Spencer’s a secret Catholic, not that that means overmuch, but it doesn’t ease my suspicions that he’s Promethean. James Burbage died in February; Richard & his brother Cuthbert head the company now. We had to tour last summer, & next summer again likely. There’s lease trouble with the Theatre: we shall have to relocate & though they have purchased the indoor theatre at Blackfriars (the one that was used by Chapman’s boy company, from whence so many of our apprentices on the common stage did come) a lawsuit by the neighbors there keeps us from using it. I suspect Baines. Or Oxford, more likely. Not that there’s a blade’s width between them. Annie bought me only the second-biggest house in Stratford, after all: she’s moved the whole family therein. My father was awarded arms in London last fall. Life seems to go on most merrily, & yet I find nothing in it to put my teeth in. Perhaps because I have lost one or two. Ned Alleyn has left playing, for good he says, & truly he has everything a man could want from it. I think he finds the modern masques & satires as wearying as I do, & misses thy pen & thy wit, sweet Christofer. Truly, he & thee were a match. Half the new satires have no play behind them but a series of jibes. Or perhaps I am old & out of fashion. Although my plays do very well. I include my Midsummer Night’s Dream, a foul copy, forgive me on the thought it might amuse thy mistress a little. Thou shalt judge if it is fit for her eyes. Thou wilt however be amused to know Ned’s still wearing that cross and since mine encounter with the Devil claiming he appeared at Faustus (I had heard the story but never credited it) September last, I’m inclined to wear one of mine own. The other news is not so cheerful. Thou wilt however laugh, I can see thee laughing to know that Her Majesty clouted Essex alongside the head recently when Essex turned his back on her. She created your old patron, the lord Admiral, Earl of Nottingham after Cadiz, & Essex was outraged that he, the Queen’s favorite, should be passed over. Burghley says he nearly drew his sword on the Queen, & the lord Admiral, now Nottingham pinned him to the floor before he could clear the scabbard, thus saving Essex’s life. Pity. My Richard II has been pirated, & I recognize the draft of the manuscript I circulated through mine old patron Southampton & his friends. I shall not make that mistake again. Sleeping, waking, heart beating or cold in earth, tis all the same. I’ve no taste for anything of late but putting words on paper. Kemp claims I must have taken a pox, I have so little will for sport. Mary’s a relief. The plays go well. I write better when I’m unhappy. There’s comfort in that of a sort. I fear I am growing old. Four & a half years ago I was young, Kit. The age most men are when they marry. My career ahead of me, London bright, Gloriana strong. Thou wert alive, & we were rivals and chambermates. The poetry we were going to write, each of us outdoing the other!

Now I am famous & a gentleman with a fine house. Edmund my brother is with us in London now: he said he could not bear to stay in Stratford. He’s a hired man with another company not with the Chamberlain’s, he said he wished to make his own way & I cannot grudge it &

Well. I’ll leave this on the mantel tonight, again, and again you will not take it. Nay, enough. More later, perhaps. As the spirit moves me.

The place on the Mermaid’s weathered door where a hand might rest to make it open was refined smooth and fair, the wood so oiled with the grease of men’s palms that it retained a fine polish although its sea-blue paint was worn into the grain.

Will found the spot and pushed, holding it wide to let little Mary slip through before him. A few ragged voices greeted them, rising from an enclave of players in the corner by the fire, half under the gallery. The October afternoon was gone chilly as the sun slipped behind a layer of overcast unlikely to bring desperately needed rain. Mary headed for the publican as Burbage waved Will to a cluster of benches maintained by the other Wills, Sly and Kemp, along with the amiable, red-goateed playmender John Fletcher, whose unbuttoned red doublet made him look like a fashion-conscious demon, and Kit’s old collaborator Thomas Nashe with his ridiculous curls.

Will limped close enough to speak in a normal tone.

“Wills. Jack, Tom, Richard.” They embraced and kissed him before he sat, which eased Will’s sore heart. He hadn’t the spleen to be angry when they treated him like Italian glass; it was, he knew, a measure of their love.

“A spare crowd tonight. Tom, you’re neither in the country nor in jail.” It had been a play called The Isle of Dogs that had seen Nashe flee London before he could be locked away on suspicion of sedition; Will glanced around the Mermaid for its second author, Ben Jonson. These satirists sailed very close to the wind. Admirable but the wind changed frequently.

“Not jailed, and drinking to it. Chapman claims he’s close to ending his revisions on Master Marley’s Hero, and he’ll be along when tis finished.” Fletcher’s eyes sparkled above his freckled cheeks, a comment on the likeliness of that.

Nashe snorted into his wine. “Kit’s four years dead. I think he would have had the poem finished in a month at most”

“Chapman has to be sure he’s eradicated all the bawdy bits. It takes a while to find them all, it being Kit’s work,” Will replied, dropping into a chair as laughter rose around him. He waited for the pause, and filled it to an approving roar, “and for George, longer than most. Where’s the bricklayer, Tom?]

Nashe tapped a pipe out on the edge of the table and twisted a knife in its clay bowl. “Ben? Still jailed.”

“No one stood his bail?”

Burbage, stretching until his shoulders cracked. “Henslowe loaned him four pound to eat on.”

“Four pound? At what rate?” Will raised an eyebrow.

Fletcher laughed. “Better than borrowing from Poley.”

“Aye, at least with Henslowe you’ll see the money and not a pile of lute strings you re supposed to sell to recoup.”

Mary came to the table balancing two mugs of thick ale, and Nashe let whatever else he might have been about to say about Robert Poley’s moneylending practices die in his throat. Mary perched on Burbage’s knee and kept one mug for herself, sliding the other neatly to Will. He cupped it, too cheerfully tired to think of fighting to swallow. The mug was cool from the cellar.

“I’ll stand Ben’s bail. How bad can it be?”

“Fifteen pound.” Nashe drained his wine.

“Significant. I’ll go tomorrow. I want him to owe me a favor.”

“You’ll have him teach you satire?” Will Sly was sly enough, on the rare occasions when he troubled himself to add to the conversation.

Will snorted. “Something like that. Richard, especially for you I come with fair news to tide us through a cold winter.”

Burbage’s head came up. “The playhouses. Yes, my merry men.”

“Hah!” That from Burbage, who slammed his fist on the trestle and kissed Mary hard enough to spill her ale.

Every man in the room looked or jumped, but Will followed the motion of one fellow in the corner, who started to his feet as if expecting a brawl, feeling for his swordhilt; Will’s cousin, the Earl of Essex’s friend, the golden-haired recusant Robert Catesby.

Will blinked: he knew both of the men at Catesby’s table. One was Gabriel Spencer, who had also been jailed for Isle of Dogs as one of the principal players, and whom Will would have expected to be sitting with the players: he raised his mug to Will as Will turned. The second, in a plain brown jerkin, was the Catholic recusant Francis Tresham. Interesting. If Sir Francis Walsingham was alive. There was not a chance that Will would inform Burghley and Robert Cecil of the same. There was comfortably Protestant and conforming in the name of the Queen, and then there were the Cecils and their mad-dog desire to see every Catholic whipped from England, and every priest hung.

Burbage clapped Will on the shoulder, drawing his attention to the table. “Oh, yes, bail Ben for that. I’ll stand half the fee. I’ll buy that Bankside property.”

“Buy?”

“No more landlords.” Burbage spat into the rushes. Kemp muttered assent.

“What about the timbers?”

Burbage shrugged. “Tis small carpentry, but great labor. We’ll pull the Theatre down.”

“And cart it over the Bridge?”

“Float. Or wait for the ice to set and skid it over.”

“Won’t your landlord have something to say on that?” Nashe asked, hunched over peppery warmed wine. He was lucky to be free of the Marshalsea. Kit and Tom Watson had spent time in Newgate themselves, an experience Will envied not.

“We’ll do it at Christmas,” Burbage said. “Betimes, I know an inn yard or two would be glad of us.

The Mermaid’s blue door rattled a little on its hinges when it opened. Will turned to see who had come in, and understand why Burbage’s voice had stopped so abruptly that it still seemed to hang in the air around them.

Sir Thomas Walsingham stood for a moment framed against the door, resplendent in a ruff starched pale yellow to compliment the canary slashes on his doublet of sanguine figured satin. A touch of gold at the buttons, the hilt of his sword, the clasp that held his cloak askew, and the pin in his hat. He’d come from court, quite obviously, and quite obviously in a hurry; his horse’s sweat stained the knees of his breeches and the insides of his hose, and his clothes were quite unsuited to riding.

“Master Shakespeare, he said from the door. If you would be so kind.”

Will stood, pushing his still-brimming tankard at Mary, and followed Walsingham out into the hubbub of the autumn afternoon. “You look like you’ve had a hard ride, Sir Thomas.”

“A fast one, in any case. And have I stopped being Tom in private through some offense, or…”

“A public thoroughfare is hardly private.”

Tom dismissed it with a tip of his well-gloved hand. “Robert Cecil sent me. After a fashion.”

“On what case?”

“Have you any progress on the Inquisitor?”

“God’s blood, man.” Will looked up as Tom’s eyebrows rose. “I forget myself, Sir Thomas.”

“I like that in a friend. You were about to say you had been on tour.”

“Aye.”

“But the playhouses are opening.”

“Aye. Oh!”

“Yes. And Cecil wants his results half yesterday.” Oh, that Walsingham smile. As if Tom looked right through you, and weighed what he saw, and was amused. A softer voice, almost too quiet to be heard over the street: “Any word of Kit?”

“No. You?”

“No.” Tom swallowed. “He always was marvelously good at making a threat stick. Will, bring Poley’s head at least to Cecil if you can, preferably Baines or de Parma. His father’s health is failing, I think,” and Will sighed, following Tom’s smooth stride over the cobbles almost without a limp. “And tis down to me and you, and Dick.”

“I’d thought of recruiting Ben Jonson. If anything happens to me, you’ll need a poet. Things are not good, Sir Thomas.”

“Nay, not good at all. No one can remember such a drought. Jonson’s rumored a recusant, isn’t he?”

“And he seems to spend most of his time in jail.” Will shrugged. “But he has talent.”

“Cecil won’t hear of it.”

“Then Cecil won’t hear of it.”

Tom coughed, and smiled. “He wants you at Westminster tonight. Privily.”

“You re a most discreet messenger. In your court suit.”

“A more usual one follows. I thought you deserved warning.”

“By Sir Thomas Walsingham.”

“William Shakespeare, Gentleman. How does it feel?”

“Like ashes rubbed between my hands,” Will said bitterly. “I’ve never written better in my life.”

The way forked. The two men glanced at one another, and turned back in the direction they had come, annoying a goodwife with a basket full of greens.

“Is there more?” Will asked.

Tom shook his head, and they continued in silence to the Mermaid’s door.

“I’d offer you my horse, but it would be a little obvious.”

“I don’t ride,” Will answered. “I’ll just slip inside and await the messenger.”

“And do try to look surprised.” Tom stopped and laughed at the expression on Will’s face. “Very well, Master Player, I shan’t teach you tricks that were old when you were a new dog too. Have a care tonight. He’s a very devil, Robert Cecil.”

“I think,” Will said, “it goes with the name.”