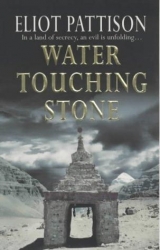

Текст книги "Water Touching Stone"

Автор книги: Eliot Pattison

Жанр:

Полицейские детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 38 (всего у книги 38 страниц)

Lokesh leaned toward Shan and explained that Gendun was going to take the waterkeeper to Senge Drak and then the waterkeeper would take Gendun to the hidden gompa.

Gendun was beaming at Shan when he looked up. "There's an old teacher at the Nest," he said with a tone of great satisfaction, "who knew my father."

"But, Rinpoche," Jowa said. "Who will go with the boy? The Yakde needs a teacher until he is ready to return."

Gendun put his hand on the waterkeeper's shoulder. "The gompa has been without their abbot for too many years."

"What is needed," the abbot of the Raven's Nest said in his raspy voice, "is someone younger and stronger. Someone trained as a monk but also trained in the ways of the world."

"The Americans spoke to me before they slept," Jowa said. "First they are going with the Eluosi, to help him buy land and build his cabin by the ocean. The boy will stay there. They can do their work there, they say, for a year or two at least. It would be a quiet place a Mao could come visit, when there are more samples to bring from the desert."

"It could be difficult to navigate from a gompa to the world, but perhaps more so to go from the world back to the life of a gompa," Gendun observed enigmatically.

Lokesh made a chuckling sound and Jowa cast him a puzzled glance.

"In the mornings," the waterkeeper said with a contented sigh, "the boy is always distracted until he eats. Just a bowl of porridge, then he studies his sutras." Jowa looked away, around the clearing, as if he expected to see another monk arriving at any moment. "But if he does well, a reward is following butterflies. One time we followed a butterfly for three hours. Someone young, with stronger legs than mine, could do it for six."

Lokesh chuckled again. Jowa looked to him, then to Shan.

The waterkeeper touched Jowa's leg. "He hates to wash his socks," the old abbot said. "Make him wash his socks."

Jowa froze and stared at the waterkeeper's fingers. "Rinpoche," he said in a whisper. "I am not-" He could not finish the sentence, but just stared at the lama's hand.

The waterkeeper leaned forward and put both hands on top of Jowa's, resting on the purba's legs. "I hear this Alaska is a wet place." He shook their hands, one on top of the other, hard, as if to make sure Jowa understood. "Dry him off sometimes."

The old lama and Jowa gazed at each other for a long time. "When he is ready," the abbot of the Raven's Nest said at last, "you must bring him back to us. There will be much work for him, in the new Tibet." He squeezed Jowa's hands again. "We will watch the oracle lake for signs."

As Jowa looked at Shan, the Tibetan's mouth slowly turned up in a grin, and Shan remembered a night that seemed long ago, standing under the moon in the Kunlun, when Jowa had spoken in despair about how the lamas would eventually disappear, about how there was no point in continuing without the lamas, and how he could never become a lama because of what the Chinese had made him. But there would be a new generation of lamas, a different breed, but lamas nonetheless, and Jowa would help nurture them.

The Yakde had risen and was standing at the fire. Fat Mao nodded at Gendun.

"We are going now," Gendun announced to Shan, and the Tibetans rose. The waterkeeper and the Yakde embraced, and the waterkeeper gestured for Jowa and embraced the Yakde's new teacher as well.

The lamas followed Fat Mao up the trail, and Shan walked the first hundred feet with them. There were no words to say. Fat Mao stepped to Shan's side, and with an awkward, sober expression, dropped something into his hand, then darted away. Gendun, then the waterkeeper, stood in front of Shan, each grinning brightly, and each in turn placed his palm over Shan's heart. Shan nodded gratefully and watched until they were out of sight, then looked into his hand. Fat Mao had given him a small, brightly colored stone, newly washed with water.

In another hour the rest of the company was on the road, waiting for a truck that was taking Lokesh into Tibet. Lokesh was full of smiles and kept holding his bag tight against his chest. More than any of them, Lokesh was certain of where he was going and what he was doing. He was going to Mount Kailas, where he would complete a pilgrimage started a thousand years before to honor a dead mother and daughter. "It's going to be cold," Shan said awkwardly, and Lokesh just smiled. "There are dangerous places, I hear," Shan warned, "where you can lose your balance." Lokesh just kept smiling his crooked smile and embraced Shan, then moved onto the road as the Maos began calling him.

Sophie was grazing on the bank of the road, where Marco lay basking in the sun. As Shan sat, the Eluosi studied him as if measuring him for something. "I'll buy you a coat in Alaska. One of those big fur coats, for the winter that Russia sends there. And a fur cap. A ushanka. You'll look like a little bear. Johnny Bear." He smiled, the first smile Shan had seen since the terrible night on the parapet, and a new thought seemed to light Marco's eyes. "We'll build a sweat lodge in the winter. Take off your clothes and get heated like the desert. Then we run out and roll in the snow. Bare Johnny." Marco laughed a small laugh, then paused with a surprised expression, as if he had not expected to ever laugh again, and the laugh erupted once more, until he was holding his belly, and Shan laughed, and laughed some more, and marveled at it, a laugh of a kind he had not felt in years. And with it came a realization of why. Because to Shan Marco was not a teacher, not a prisoner, not a student, not a warrior. Marco was only a friend.

Shan watched as Jowa, his eyes burning with a brightness Shan had never before seen in them, threw a ball with Deacon and the boy lama. Sophie nuzzled his ear and Marco spoke again of the cabin he would build. A butterfly passed by and Shan turned to see Jowa pointing it out to the boy.

The sound of a struggling engine reached his ears and a moment later a decrepit vehicle came into view, a decades-old cargo truck. Its rear bay, covered with a soiled, torn canvas, was nearly filled with crates of chickens. Lokesh laughed as the Maos helped him on board, into a space between the crates.

Shan could not take his eyes off the old man, going alone into the inhospitable Himalayas. He realized suddenly that he was standing, and his hands were trembling. He felt his mouth open and shut, but no words came.

At his side he heard Marco sigh heavily and saw him rise to work on Sophie's saddle, where their bags were tied. "On the other hand," Marco boomed out, as if for dramatic effect, "it can rain for weeks in Alaska. Hard place, if you're used to looking at the sky." Something landed at Shan's feet. His bag.

Lokesh was settling into the truck. Chickens were squawking irritably and fluttering in their crates. The Maos were waving at the old Tibetan, fond smiles on their faces. The engine sputtered back to life in a cloud of smoke and with a groan the truck began to climb the mountain again.

Shan looked into the Eluosi's eyes. "It's a lot of chickens for one man," Marco said in a grave tone, and something seemed to catch in his throat. He grabbed Shan's hand and clasped it hard for a moment, then handed him his bag. Shan only nodded, then took a small step, and another, then began to run. As he jumped on the bumper of the moving truck, his shoulder swung back, pulled by the weight of his bag. Then, just as Shan was losing his balance, a thin hand, spotted with age, reached out and pulled him inside.

Author's Note

While the characters and most of the places in this book are fictional, the struggle of the Tibetan, Kazakh, and Uighur people to maintain their culture and identity is very real. Many elements of this story are distilled from actual events in that fifty-year struggle, and from the rich and fascinating heritage of the Silk Road. The sands of the Taklamakan desert do indeed sometimes part to reveal ruins of lost Silk Road cities and tombs, and dedicated archaeologists from many nations do indeed work among the ruins, and do find ancient mummies and textiles, despite the political storms which rage around their work. Genetic research in the region and even scholarly assessment of scraps of cloth have attracted such political controversy that the simplest quest for knowledge in those distant quarters can be an act of heroism. And sadly, in Tibet the government of modern China has repeatedly interjected itself in the identification of reincarnate lamas.

For those readers who wish to learn more, many excellent sources are available, and deserve recommendation. Perhaps the most comprehensive works describing the Tibetan experience are John Avedon's In Exile from the Land of the Snows, and The Dragon in the Land of the Snows by Tsering Shakya. The many excellent first hand accounts by or about Tibetan survivors include A Strange Liberation: Tibetan Lives in Chinese Hands, by David Patt, Ama Adhe: The Voice that Remembers, by Adhe Tapontsang and Joy Blakeslee, Palden Gyatso's Autobiography of a Tibetan Monk, and In the Presence of my Enemies, by Sumner Carnahan. The details of the most public of Beijing's interventions in the selection of Tibetan reincarnations are set forth in Isabel Hilton's important work The Search for the Panchen Lama.

The fascinating horse-based culture of the Kazakh people is well described in Kazakh Traditions of China, by Awelkhan Hali, Zenxiang Li, and Karl W. Luckert, and China's Last Nomads, by Linda Benson and Ingvar Svanberg. Elizabeth Wayland Barber captures the remarkable archaeological discoveries being made in the Taklamakan in her The Mummies of Urumchi, which are explored even more comprehensively in The Tarim Mummies by J.P. Mallory and Victor H. Mair. Lastly, for any readers inclined to learn more about the world of cricket singers, Lisa Gail Ryan's Insect Musicians and Cricket Champions provides a lyrical introduction.

Glossary of Foreign Language Terms

Terms that are used only once and defined in adjoining text are not included in this glossary.

Aksai Chin. A border region located where the Kunlun Mountains meet the Karakorum range, in the far southeast of Xinjiang, on Tibet's far northwestern border. Ownership of Aksai Chin is disputed between India and China, although it is occupied by the Chinese.

ani. Tibetan. A Buddhist nun.

ashamai. Turkic. A special soft saddle traditionally presented to Kazakh children when they reach the age of five, the age at which they typically stopped riding with their parents and began riding alone.

bumpa. Tibetan. A treasure vase, or ceremonial water pot, used in Buddhist ritual.

besik zhyry. Turkic. A cradle song.

changtang. Tibetan. The vast high plateau which dominates north central Tibet.

chuba. Tibetan. A heavy cloak-like coat made from sheepskin or sometimes thick woolen cloth.

dombra. Turkic. A two stringed lute-like instrument.

dopa. Turkic. A round brimless cap often worn by devout Muslims.

dorje. Tibetan. From the Sanskrit "vajre," a scepter-shaped ritual instrument that symbolizes the power of compassion, said to be "unbreakable as diamond" and as "powerful as a thunderbolt."

dorje bell. Tibetan. A bell with a dorje handle.

dropka. Tibetan. A nomad of the changtang, literally "a dweller of the black tent."

Eluosi. Mandarin. A Russian, used to describe the Russian emigres who live in Xinjiang.

gau. Tibetan. A "portable shrine," typically a small hinged metal box carried around the neck into which a prayer has been inserted.

gompa. Tibetan. A monastery, literally a "place of meditation."

jinni. Turkic. A type of evil spirit.

karaburan. Turkic. A sand storm, specifically used for the "black hurricanes" that plague the Taklamakan desert.

karez. Turkic. The underground water system, consisting of tunnels, cisterns, and access shafts, which uses gravity to transport water from mountain springs to distant farms and communities. Some elements of the karez system in Xinjiang date back two thousand years.

khampa. Tibetan. A native of the Kham region of what was traditionally eastern Tibet.

khata. Tibetan. A prayer scarf, traditionally of white silk or cotton, often offered to a lama at the end of a ritual.

Kharoshthi. A language of Aramaic origin dating to the fifth century B.C., which was commonly used on the early Silk Road.

khez khuwar. Turkic. A Kazakh riding game, traditionally played between girls on one side and boys on the other.

khoshakhan. Turkic. A calming call made to lambs.

kumiss. Turkic. Fermented mare's milk, often carried in a leather drinking skin.

Kunlun. The high, long mountain range that defines the northern border of the Tibetan plateau, extending from the Pamir and Karakorum ranges on the Pakistan border for several hundred miles to the east.

lama. Tibetan. The Tibetan translation of the Sanskrit "guru," traditionally used for a fully ordained senior monk who has become a master teacher.

lao jiao. Mandarin. Literally "reeducation through labor," referring to a less severe incarceration facility where prisoners receive intense political education.

lao gai. Mandarin. Literally "reform through labor," referring to a prison labor camp.

lung ma. Mandarin. Traditionally, a "horse dragon," a mythical beast, part horse, part dragon, that brought justice to the common people.

lha gyal lo. Tibetan. A traditional Tibetan phrase of celebration or rejoicing, literally, "Victory to the gods."

mala. Tibetan. A Buddhist rosary, typically consisting of 108 beads.

mani stone. Tibetan. A stone inscribed, by paint or carving, with a Buddhist prayer, typically invoking the mantra Om Mani Padme Hum.

mani wall. Tibetan. A wall made of mani stones. Traditionally pilgrims visiting a shrine would add a mani stone to such a wall to acquire merit.

Mei Guo. Mandarin. America, literally, "Beautiful Country."

mudra. Tibetan. A symbolic gesture made by arranging the hands and fingers in prescribed patterns to represent a specific prayer, offering, or state of mind.

nadam. Turkic. Traditionally, a Kazakh horse festival, where Kazakh clans gather for several days to engage in horse racing, and other athletic competitions.

nan. Turkic. Flat bread, traditionally baked on a stone.

nei lou. Mandarin. State secret; literally for government use only.

pecha. Tibetan. A traditional Tibetan book of scripture, typically unbound in long, narrow loose leaves which are wrapped in cloth, often tied with carved wooden end pieces.

purba. Tibetan. Literally "nail" or "spike," a small dagger with a triangular blade used in Buddhist ritual.

Rinpoche. Tibetan. A term of respect in addressing a revered teacher, literally "blessed" or "jewel."

Sekset Ata. Turkic. The deity who protects goats.

sundet. Turkic. In Kazakh tradition a boy is circumcised between the ages of five and seven, in a ceremony called sundet toi. Often a pony is presented to the boy by his family at this time. Later in life this is referred to as the boy's sundet horse.

synshy. Turkic. A "knower of horses," or "horse speaker," who is thought to have special abilities to communicate with a horse and discern its personality, attributes, and illnesses.

Taklamakan. Turkic. A vast desert in south central Xinjiang, between the Tian Shan mountains in the north and the Kunlun range in the south, known for its extreme temperatures and treacherous shifting sands.

tamzing. Mandarin. A "struggle session," typically a public criticism of an individual in which humiliation and verbal and/or physical abuse is utilized to achieve political education.

tsampa. Tibetan. Roasted barley flour, a staple food of Tibet.

tsingha. Tibetan. Small cymbal-like chimes used in Buddhist ritual.

thangka. Tibetan. A painting on cloth, typically of a religious nature and often considered sacred.

torma. Tibetan. A ritual offering made primarily of butter and barley flour, shaped and dyed in many shapes and sizes in homage to Buddhist deities.

Urumqi. Mandarin. The capital of Xinjiang.

Xinjiang. Mandarin. The Xinjiang Autonomous Region, the name given by the People's Republic of China to the huge region bounded to the northeast by Mongolia, on the east by the Chinese provinces of Gansu and Qinghia, on the south by Tibet, and on the west by Kazahkstan, Kirghizstan, Tajikstan, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India.

zheli. Turkic. The rope stretched between pegs or trees to tether young animals.

Zhylkhyshy Ata. Turkic. The deity who protects horses, also called Khambar Ata.