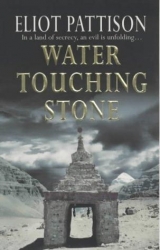

Текст книги "Water Touching Stone"

Автор книги: Eliot Pattison

Жанр:

Полицейские детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 15 (всего у книги 38 страниц)

A movement below broke the spell. A dark, hulking shape, barely lighter than the shadows it moved in, stole along the back of the domed building. It made no sound, and the animals in the pen ignored it, almost as if they could not see it. Ghosts roamed the Taklamakan. For centuries Karachuk had been a city inhabited only by ghosts, Jakli had said.

The phantom glided toward the rocks now, stopping every few seconds as if to listen or watch. Lau's killer had moved like this, unseen in the night. And Lau had not been killed by a ghost. It could be the killer again, he thought, or a thief. But who would risk the wrath of Marco?

The figure should have been close enough for Shan to hear its feet on the gravel at the base of the rock, but there was no sound except the crickets. The thing bent over on all fours and moved closer to the outcropping, only fifty feet from Shan now. Suddenly a brilliant light flashed from the shape, followed by a sound of glee, then the light disappeared and the grey thing hurried back toward the compound.

Shan launched himself from his perch and ran down the path, jumping onto the sand and darting to the shadows at the rear of Osman's inn just as the figure disappeared around a hut at the far side of the corral.

The horses trotted away from him as Shan approached. They had not been frightened by the figure who had gone before, only by Shan. The big camel, so silvery in the moonlight that it too seemed like an apparition, made a sound that started as a snort and ended in a low, throaty grumbling sound, as if first it were alarmed and then just angry at being disturbed.

The hut had no window. As he approached it Shan saw that its plank door was ajar, and he gently pushed it open a few inches. A thick rug had been hung over the inside frame, concealing a dim light from within. He slipped inside and saw to his surprise a wall of neatly trimmed boards that had been expertly fitted into the structure only three feet inside the entrance. A narrow plank door with a hasp for a lock hung open enough to leak the brilliant white light of an incandescent bulb along its edge.

Shan waited in silence for several minutes, then laid a finger against the wooden door. It swung inward a few inches, enough for him to see a table nailed together of rough planks, stacked with books.

"It's open," someone said in Mandarin.

Shan pushed the door and stepped inside. Deacon, the American, was standing at a workbench under a naked lightbulb, examining something under a large magnifying lens that was suspended by a swinging arm clamped to the table. Without turning around, he gestured toward a bottle on the table. "Help yourself to the vodka."

Shan silently surveyed the room. The electric line for the bulb ran to a wooden box in the corner, containing a series of heavy batteries. The books, in English, German, and Chinese, appeared to be textbooks on anthropology and archaeology. Another volume, thicker than the others and leaning open at the back of the table, seemed to be on a different topic. It was held open by a heavy spring clip to a diagram of a human skeleton.

"If you've grown particular, there's a clean glass on the shelf above the door," Deacon said, then glanced over his shoulder. He paused and raised an eyebrow, then returned to his work. "It's you," he said impassively. "Expected a Russian."

Shan did not immediately reply, for, an instant after Deacon had noticed him, his own eyes had found a shelf hung above the bench where Deacon worked. It held half a dozen small cages, all different but each one constructed of finely worked wood. They all glowed with the patina of great age. The largest, perhaps six inches long and four in height and depth, was made of thin slats of sandalwood. The smallest appeared to have been crafted out of a solid piece of fruitwood, hollowed out and carved into the shape of a temple.

The cruelest thing they had done to him in the gulag was to steal his memories. The pain from his repeated interrogations, from batons sometimes, and drugs, and electric prods, had dulled his memory, had made certain parts of his brain seem inaccessible. It was part of the Party's master plan, a cellmate had said, to cauterize the brain so it could not remember that once things had been better. But on seeing the cages something vague had jarred loose in the back of his mind.

At least three of the cages appeared occupied.

Deacon had followed Shan's gaze. "Marco laughs at me, but I tell him every proper town needs its own orchestra."

"You were outside," Shan said, then added with sudden realization, "you were gathering singers."

Deacon looked at the cages with a satisfied grin. "Got him, finally. Old Ironlegs, we call him. Makes a rasping sort of song, like his leg is made of metal." He turned to Shan. "You know crickets?" he asked in English.

Shan looked at the American in silence and slowly grinned. It seemed a wonderful question. "When I was young," he said, awed that the memory should have leapt out and found his tongue after being lost for so many years, "my father would take me to an old Taoist priest who had avoided all the suffering in the cities by fleeing to the mountains. He lived alone and spent most of his time weaving baskets and meditating on the Taoist scriptures. The only other thing I remember about him is that he collected singers. He taught me about them." How remarkable, Shan thought, to be in the desert, with a strange American, looking for a killer, and suddenly have one of the darkened doors of his memory opened.

Deacon smiled. "My first trip to China, I went to a market and saw a vendor selling insect singers. Had maybe fifteen species. A horse bell. A stove chicken, with the big antennae. Some of the black ones, ink bells they're called. And a weaving lady."

Somewhere deep inside Shan, something warmed as he heard the names, names he had first heard with his father, decades earlier. "I remember one called a cao zhong," he said. The words came unexpectedly, on a flood of recollection. "A beautiful one, loud but perfectly pitched. I don't know the English."

"A grass katydid," Deacon said. "God, I'd love to have a katydid. Too dry here." The American's eyes filled with pleasure as he gazed at his cages. "That street vendor, I sat with him for two hours as he explained how each had different songs, how their diet could affect their song, how the emperors used to have tiny furniture made for their favorite crickets. Next trip, I took my son Micah to see him again. All Micah did was grin, the biggest, most beautiful grin I ever saw on his face. We were hooked." Deacon looked with pride at his collection of cages. "The vendor told us they bring good fortune."

Shan nodded. "Because their song is so alive and bright. Living music, the old priest called it. Because you can't control them. If a cricket chooses to bring his living music to your home, then nature has indeed blessed you." Shan pried the door of his memory open further. "I remember one called a blue bell, and a painted mirror." He rushed the words out, as if scared of losing them again. "And a bamboo bell."

"With Ironlegs my chorus is complete. He's a watchman. Pang t'ou, they call it. Watchman's rattle. Full moon in ten days. My son and I will take them out into the dark at midnight and listen to their chorus. We'll watch for shooting stars. One of the old Kazakhs told my son that some crickets can do that, call in shooting stars."

"Your son?" Shan asked. "Your son is here?"

"Not here, but in Xinjiang."

For an agonizing moment Shan's mind raced. No. Deacon couldn't be old enough to be the father of the dead American at Glory Camp. "How old is he?"

"Ten." The American pushed the lens away and surveyed his cages again. "They'll attack each other if you don't keep them separate," he said, as if eager to shift the conversation from the boy called Micah.

"The old priest had a lot of antique cages, like yours, and some made of gourds," Shan recalled. "Others he made of bamboo splints or reeds."

"They're hard to find, the old cages. What happened to his?"

Shan smiled sadly as that part of the memory flooded over him. His father had left him with the old man one night, and they had stayed up until the crickets stopped singing in the early hours of the morning. "One of the few people who knew about him was a shepherd boy who brought rice cakes to him on festival days. But the boy joined the Red Guard and had a quota of reactionaries to arrest."

"Christ," Deacon muttered, as if he recognized the story.

"One day the boy came and told the old man that he would have to tell his platoon leader about him, that they would come the next day to take him away."

"Jesus. What did the old man do to the boy?"

"He thanked the boy for showing him respect," Shan said with a sigh. "That night, because the cages were from imperial China and he knew they would be crushed by the Guard, he freed all his singers. Then he waited until the moon rose and he burned all the cages. I know because my school class was required to go to the trial. The Guard was furious, because he refused to condemn the Taoists, and he only talked about that perfect moment, in a serene voice, about how the crickets had stayed and watched the fire and sung their most beautiful song ever as the cages burned. We were forced to leave, because the old man didn't follow the script." There had been another trial later, he recalled, when the Red Guard had begun to exhaust the supply of ready victims. They had arrested a vendor of crickets and put the insects on trial for contributing to the reactionary tradition. In the end they had roasted all the crickets on tiny spits and made the man eat them.

The laptop computer beeped and the screen went blank. Deacon took a step toward the workbench and closed the cover.

"I didn't know there was electricity," Shan said. "There wasn't any at Osman's."

"Only here. A portable solar rig. Charges the batteries enough for four or five hours' use."

Solar cells and crickets. A computer in an ancient Silk Road hut. An American hiding in a Chinese desert, drinking vodka with a Russian renegade. Jakli had taken him to another world, or several other worlds, none of which seemed connected to Lau or Gendun or the dead boys.

Shan could see the back table now, where Deacon had been working. The lens had been over a piece of cloth, an old faded textile with a crosshatch pattern of threads colored in shades of brown, yellow, and red. Deacon stepped forward, blocking his view of the table.

"Why are you here, Mr. Deacon?" Shan asked.

"Deacon. Just Deacon. I told you. Collecting crickets."

"I mean here, in Karachuk. In the Taklamakan. In Xinjiang."

Deacon smiled thinly and looked up at his crickets. "Maybe because of that grin on my boy's face. Hard to come by, back home." He looked at Shan. "Or maybe for the same reason as Marco, and Osman, and Jakli, and Nikki."

"You mean to hide?"

The American shook his head solemnly. "To the contrary. We came here to stop hiding. Here is where no one can hide."

"We?" Shan asked. "You and your son?"

Deacon frowned. "My wife and I."

"I thought that hiding was the point of Karachuk. Smugglers. Outcasts. They come here to hide."

"Then you don't get it. I've been everywhere, on every continent, even the Antarctic. This is the only place I know on earth where you're totally responsible for yourself. No police. No soldiers. No goddamned government to tell you what to think or to make it easy for people not to think. You have to be somebody here. You have to trust and be trusted."

Shan stepped closer to Deacon's worktable. Deacon moved to block him. "You have to trust," Shan said, repeating the American's words.

Deacon frowned. "You didn't say what happened to that old priest with the crickets."

Shan looked at the cages once more. "They beat him at the end of the trial. Then they forced other priests to beat him. He died and they burned his body, all on the same day they took him from the mountain." Shan sighed and looked at the cricket cages again. "My father got some ashes from where the fire was and he took me back there, to where the priest had lived. We made a secret shrine for the ashes. When we left at dusk the crickets were singing for him."

The American stood still and let Shan push past.

It was indeed an ancient textile Deacon had been studying, a piece of thickly woven reddish-brown fabric. The cloth was wrapped around something cylindrical, covered at one end with a bit of canvas. To the right was a small binocular microscope.

"Textbooks say you can only dye white wool, wool without natural pigment," Deacon said over his shoulder. "But in the Taklamakan they never read those books. This is wool from a brown sheep, with most of its threads colored with a red-purple dye through some process we don't understand yet." Deacon pointed to the crosshatch pattern. "Here, they wove with strands of undyed white wool and white wool dyed red."

Shan looked at him in confusion. Surely the American hadn't come halfway around the world to secretly study cloth.

Voices suddenly broke through the silence outside. Multiple voices, a commotion of running and shouting. Someone called for Marco. Deacon looked back at his door but seemed reluctant to leave Shan alone.

Someone shouted the American's name. The door swung open, but no one was behind it. As Deacon stepped toward the opening, Shan quickly pulled away the canvas at the end of the textile.

He stared in disbelief, fighting a sudden nausea. The fabric had been a pants leg. Extending from it was a human foot, small and shriveled, but unmistakably a foot.

"Shit," the American muttered, his eyes moving from Shan to the door.

Somebody shouted again and Marco's huge frame filled the doorway. He gestured for them to come out and retreated far enough for Shan to see Akzu behind him, looking so exhausted he could barely stand. Jakli ran up, holding a blanket around her shoulders.

"Someone killed a Public Security officer," Akzu gasped. "Lieutenant Sui. The knobs will be crawling all over the county in a few more hours. They will declare martial law." The Kazakh pronounced the words like a death sentence, then turned to Shan and the American as though further explanation were required. "Arrests will made, lots of arrests. Soldiers will sweep everywhere. Everyone must flee. They're going to take our families."

Chapter Eight

In the early morning light the stone sentinels of Karachuk seemed to have crouched, as though coiled for battle, sensing an approaching enemy. Indeed, the news brought by Akzu seemed to have transformed most of the town's inhabitants. The bright clothing Shan had seen the day before had been replaced by shades of brown and grey that blended with the desert. Long knives had appeared on many belts and, to Shan's great discomfort, rifles were slung on the shoulders of some of the Kazakhs.

He found Akzu and Osman at the corral, speaking in hushed, hurried tones.

"Where was Sui killed?" Shan asked. "Usually these things happen in the cities. Surely they wouldn't suspect the herdsmen."

"On the Kashgar highway," Akzu sighed, "twenty miles outside of Yoktian. No one lives there but Kazakh and Uighur herders. You know what the knobs will do. Sweep the camps for political undesirables. Curfews will be imposed. Four years ago when an army sergeant died martial law was declared for six months. Suspects were sent directly to the coal mines, their families to Glory Camp. The fools who did it have no idea of the suffering they will cause."

"What fools?" Shan asked. "You know who did it?"

Akzu was gazing toward the mountains. "Malik is still out there. He brought a boy back to us, then left again. Now my sons have gone too, to gather those of the zheli who can still be found." He turned to Shan as if just hearing his question and shrugged. "The Maos. It's what they do. That's who did it four years ago. The hotheads. The ones who think change can come overnight."

"Think?" a loud voice interjected over Shan's shoulder. "They don't think. They're just arrogant predators, as bad as the knobs sometimes. An easy kill comes along, bang. They just satisfy their appetite and move on." Marco didn't seem frightened like the others. He only seemed angry. "The whelps! How dare they do this to us!"

Surely the murder would mean added pressure from Public Security. But Marco's rage seemed more focused, as if the incident meant interference with a particular plan.

The Eluosi's fury choked off as he looked in the direction of the outcropping. His oxlike breathing dominated the silence. Shan followed his gaze toward the highest point. Jakli was sitting there, arms around her raised knees, watching the western horizon.

"Mother of God," Marco said, his voice suddenly soft and pained.

"She fears for her– for your son?" Shan asked awkwardly.

"Not that," Marco muttered. "Nikki is fine. Nikki is invincible." He kicked the wall of the building. A piece of the old mud stucco fell away.

"Something else," Osman explained. "If the knobs mobilize, they will check all undesirables. She is supposed to be at her factory job in town. A violation of probation, not to be there. Her friends cover for her, because her friends know it is for Auntie Lau. Everyone loved Auntie Lau. Normally the knobs won't bother to check there. But now, with Sui dead, they are bound to look everywhere. No one can cover when the knobs come looking for her. If they arrest her," he said, turning to speak toward the distant mountains, "she won't be at the horse festival. She won't be getting married. They'll take her to one of the coal mines. I was at a coal prison once, delivering food with some Maos. Hammers and chisels is all they get. No gloves. No mining machines. Never enough food. I saw prisoners whose hands were nothing but bone and skin, like skeletons." He looked back at Jakli. "So young," he said in a near whisper, "so full of life. A few months in a coal mine and she'll be old and empty."

The silver camel in the corral made a snickering sound. Shan moved to the corner of the building just as Osman led two horses behind the nearest hut, one saddled, the other bearing a heavy load of crates with canvas lashed around them. Where was he going? To warn his family? To make a suicidal dash across the border? He studied the others, nearly all mounted now. They looked more like a raiding party than a band of refugees.

A gust from the east blew a sound toward him. He turned and saw that Jakli was standing now, waving at someone. It was a mounted man, trotting briskly toward the north of the compound, toward the heart of the endless desert. Shan caught movement out of the corner of his eye. Osman appeared, nodding toward Marco. Shan swung his head back toward the rider. It was Deacon. The American was trotting alone into the desert, leading the pack horse.

Shan quickly walked to the hut the American had been using. Two men were in front of it, shoveling sand against a barrier of sunbleached planks that had been set against the entrance, which itself was now blocked by a heavy beam, arranged to look like it had dropped from the roof. The hut was being transformed back into a ruin.

Shan paced around the building. It had no other opening, except a small chink in the wall at ground level where, he surmised, the conduit for the solar panels had run to the batteries. As he stared at the hole one of the men threw a shovelful of sand to cover it. No, Shan almost protested, there are singers inside. Old Ironlegs had to be fed. But in the same instant he knew somehow that Deacon had taken the crickets with him. In the few minutes Shan had spent with him he had sensed that there were few things more important to Deacon than the date he had with his son, Micah, the rendezvous to sit with their singers under the full moon.

But was the other thing still inside? The appendage, the human leg. What had the American been doing with it? Dissecting it? Gloating over it? Whose leg had it been? Shan realized that perhaps it had not been as old as it first appeared. This was the desert, where things became desiccated almost overnight. Perhaps it had been someone who had died recently. Perhaps Deacon was doing his own detective work. Only then did he remember Bajys' words about his desperate search at Karachuk. About how he had found pieces of people, like in the paintings of demons.

Shan saw that all of the huts in the hollow had been reduced to apparent ruins by the addition of sand and ancient planks to blend in with the rest of Karachuk. As he watched the evacuation sadness flooded through him again. He had been mistaken, of course, to think he had arrived in another world. This was the same world, the world of knobs and bloodstained Buddhas.

He felt a sense of loss, a sense of defeat, as he absorbed the news of Sui's murder. It meant he would be unable to travel anywhere, that everyone, including the murderer, would drop into holes, doing their best to disappear for what could be weeks, even months.

Marco was with the silver camel at Osman's door when Shan rounded the corner of the building. Shan had not really studied the animal before, but as he looked at her he realized she was unlike any of the creatures he had yet seen in Xinjiang. Her eyes were bright with intelligence, her hair lustrous. Her head was bent to one side as she looked back at him, as though cocked in curiosity. To his surprise he saw that her left ear was pierced with a small, elegant silver ring.

Shan stepped forward as Marco hoisted a simple wood-frame saddle between the animal's humps. The camel bent her head still further, then pushed her nose into Shan's hands and licked them.

Marco stared at her uncertainly. "Sophie! You harlot!" he barked and scratched the camel between the ears. "She doesn't do that," he said with a puzzled expression. "Only for family. For me and Nikki. And Jakli," he added.

"She's handsome."

Marco hugged the camel. "She's beautiful. Like a beautiful woman. The Emir of Bukhara," he said, referring to the ruler of one of the ancient walled cities of central Asia, "had a stable of two hundred racing camels until the Bolsheviks laid siege to his city. For three years the Emir fought from the city walls. The Bolsheviks built a damned railroad right up to the walls while he watched helplessly. Had to feed most of his camels to his troops. But when the Bolshevik troop trains began arriving, he made the bastards promise safe conduct for the surviving twenty camels and their grooms before his surrender. He refused to let the invaders in until he saw the camels were free. Sophie came from one of those survivors."

Shan dared to put his hand on the camel's neck. Sophie pushed against him as though asking for him to rub it. He did so. "I thought Karachuk was safe."

Osman carried out two large pannier baskets stuffed with smaller boxes and bundles wrapped in cloth. "The safest of places," Marco agreed. "Next to my home. Which is why we won't risk it. Knobs never venture this far onto the sand. But when this kind of trouble hits they call in helicopters. They see us down here and-" He shrugged and looked at Osman. "Then no more week-long chess games, right, old friend?" He stepped to a smaller camel standing behind Sophie and helped Osman tie the baskets to her pack frame.

Jakli appeared behind Sophie, looking worn and fretful. She was carrying Shan's drawstring bag.

"You need to go home, Chinese," Marco said.

"I have no home."

"All right, Back to Tibet."

"I am not finished."

"Sure you are. The knobs are finishing it." Marco seemed to see the determination in Shan's eyes. "The hornet's nest has opened up. You don't want to push another stick up it."

"I cannot stop unless asked by those who sent me here," Shan said quietly.

Marco shook his head. "They don't know this land. You don't know this land." He looked past Sophie's neck toward the desert. "It's the way it has always been. Like a tide on the great sea, the beast comes. People build a good life around a herd, an oasis, a small valley in the mountains. Every few years it is swept away. They know it. They come to expect it. Long ago, when Karachuk was fertile, sometimes locusts came and ate everything green for a thousand miles. Sometimes, before the desert finally consumed everything forever, it was a giant sandstorm, a karaburan, the kind that can blow for days and destroys anything softer than a stone. Sometimes it's an army. The Mongols invaded. The Chinese invaded. The Persians invaded. They say the Romans invaded once. If you believe all the stories, even an army of tigers invaded, ridden by monkeys." He looked back at his knots, gave them a final tug and unwound Sophie's reins from her neck.

"Monkeys on tigers, knobs on tanks, it's all the same. If you want to live and keep those important to you alive, you fade away. Become invisible. Go underground. Go to the high mountains. Just get out of the path of the beast."

Shan well knew the beast Marco referred to. He had been swallowed into its belly for over three years. "The beast doesn't always have to win," he said stubbornly. Jakli was near him now, looking anxious to be gone.

Marco stared soberly at Shan. "That," he said after a moment, "depends on how you define winning." He turned and nuzzled his face into the thick hair on Sophie's forehead, as if consulting the animal. "Look, Comrade Inspector," he said, lifting his head, "Jakli says you have no papers at all. Let her take you back to shelter. Wait a week or two at least. Go to Red Stone clan. Count the sheep."

Shan did not move, did not take his eyes off Marco. "Red Stone has enough troubles of their own."

The Eluosi frowned and shifted his gaze to Jakli. He stroked his beard and glanced at Osman, as though remembering the innkeeper's warning about the coal mine prisons. "You have to hide, girl. Come with me. Don't get taken now, not so close to the festival."

Jakli smiled and, standing on her toes, kissed Marco on his cheek. "I'm staying with Shan," she declared brightly. "I made a promise to Lau."

But you also made a promise to Nikki, Shan almost said, then he looked into her eyes and realized it wasn't simply defiance he saw there. She had made a vow not just to Lau but to herself. She had to find justice for Lau before she was married.

Marco stepped back, rubbing his hand on his cheek where she had kissed him. The boisterous Eluosi seemed at a loss for words. "Damn it," he muttered, "then take him to Senge Drak," he said to Jakli. "Shan's their problem, not ours."

"Senge Drak?" Shan asked, looking to Jakli.

"In the Kunlun," Marco said, and paused with a meaningful look at Jakli. "Whoever killed Sui could be there," he said to her in a quizzical tone, as if the thought had just occurred to him. He turned back to Shan. "You want to stop the beast? Then take Sui's killer to the knobs."

The whinny of a horse interrupted Marco. They turned to see the remaining men of the compound mounted and moving in single file up the path that Shan and Jakli had taken the day before. The riders at the top of the column had stopped and were waving.

As if understanding the distant gesture, Sophie knelt in the sand for Marco to mount. The instant he was in the saddle she leapt forward at a trot. An energetic laugh escaped the Eluosi. "May the god of all creatures watch over you, Chinese," he called out. "Since I cannot." In a few seconds he was at the head of the column.

A strange emotion surged through Shan as he watched the line of riders and pack animals file out of the compound. It was a sight out of the past, out of the Silk Road, out of Karachuk as she was meant to be. A caravan of adventurers heading toward dangers known and unknown.

Jakli steered in a new direction as she drove the truck away from the ruined city, straight south, toward the high peaks that were the walls of Tibet. Toward the edge of beyond. Shan watched the barren landscape, fading in and out of wakefulness as the truck rocked along another river bed. After an hour Jakli stopped in a grove of willows and poplars by the Kashgar highway and asked him to climb out to confirm that no other vehicles were in sight. He waved her across, and they followed another stream bed for a mile until, with a lurch of speed, Jakli shot over the bank and onto a track just wide enough to accommodate the truck.

Shan studied the map on the seat. "It's not far to Glory Camp," he observed.

"Too risky for that again," Jakli said, shaking her head. "Not with knobs watching. Not after what Xu did with you."

"There were sheep on the hills over the camp," he said, and explained what he wanted to do.

Jakli sighed and stopped to study the map again. Half an hour later they had parked in a clump of trees and were climbing over a low ridge that ran along the east side of the rice camp. Halfway up, Jakli stopped him with a hand on his shoulder, then whistled sharply. Thirty seconds later a huge dog appeared above them, followed by a man whose face showed no sign of welcome. They approached the man, who acknowledged them with a conspicuous frown, then bent over the dog and ordered it away with a low command.

The shepherd pulled a pair of high-powered binoculars from his neck and handed them to Jakli, then spun about and led them up the trail. As they passed under a large poplar tree near the crest of the ridge, the man muttered a word of the Turkic tongue, and the same word was called back from above. Shan looked up to see a second man perched with another set of binoculars. They weren't shepherds. They were Maos.

Jakli handed the glasses to Shan as Glory Camp came into view and motioned him into the shadows of a large shrub. Nothing unusual was happening yet, Shan heard the man report to Jakli as he surveyed the compound. No more truckloads of detainees. The prisoners were in class. The grounds were empty. The building with the holding cells appeared quiet.

"Nothing," the man repeated impatiently to Shan's back.

But there was something. At the flagpole in the center of the compound, a compound, a grey shape that could have been mistaken for a rock. He pointed at it.