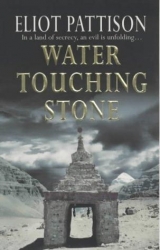

Текст книги "Water Touching Stone"

Автор книги: Eliot Pattison

Жанр:

Полицейские детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 27 (всего у книги 38 страниц)

Gendun looked out into the night. A shooting star burst across the horizon below them.

"He was a friend of mine," Lokesh said in his distant voice. "Once, when I was a small boy, he saved me in a snow avalanche. He pulled me in and held me behind a rock as the snow tumbled over a cliff." He smiled. "After that we walked and found high places where we recited the sutras." He reached out and placed his hand around the battered cup from the boy's bag. "He carried this cup, and we would drink with it from mountain springs. We played with dogs and looked for caves. Sometimes we found things left by hermits."

"Khitai?" Shan said in a helpless voice.

Lokesh nodded and sighed with a strange dreamy expression. "Once on the Dalai Lama's birthday we climbed a mountain and threw paper horses into the sky," he said, referring to the old custom of sending paper horses into the wind. When they were found by needy travelers they would turn into flesh and blood creatures. Lokesh drifted back to the brazier and dropped in several juniper splints, then saw the confusion on Shan's face. "He wasn't called Khitai then. He was Tsering," Lokesh spoke with a satisfied smile, as if he had explained everything. "Tsering Raluk."

"And before that," Gendun prodded.

Lokesh shrugged. "Before that he was born in Kham, with the name of Dorjing." He looked at Gendun, who nodded for him to continue. "Before that his incarnation name was Ragta, born in Amdo. Before that, my brain is in shadows. In a long ago time I remember there was a boy in Nepal."

Shan found his way to the table and dropped onto the bench. "I don't understand. Incarnations have no prelife memories. They have no direction over where they reemerge."

He looked at his two friends, who stared at him with wide smiles, like children sharing something wonderful.

"Ai, yi," Shan whispered in realization. "He is a tulku." He never felt more ignorant than when the truth slammed into him, never more blind than when at last he could see. It wasn't a boy they were after. It never had been. He walked back to the exposed portal, and stood where the wind, now quite chilling, hit him with its full strength. He closed his eyes, his mind racing, and let the wind do its work, peeling away the chaff. A tulku was a reincarnate lama, a soul so evolved it could direct its reincarnation, could even have memories of its past incarnations.

"There was a gompa in the mountains halfway between Mount Kailas and Shigatse, for many centuries one of the largest in Tibet," Gendun explained. "The first abbot was a tulku, the Yakde Lama, the leader of one of the old sects, one of the lost sects." Although traditionally Tibet had been led by the Yellow Hat, the Gelukpa sect, many other sects had existed in the country, most small and nearly extinct, some tiny but still vitally alive after all the centuries. "Or nearly lost. The last Yakde Lama had a dozen gompas, small ones, mostly built during the old empire period. He had always trained at Shigatse as a young boy," Gendun said, referring to the huge Tashilhunpo gompa that had once dominated Tibet's second largest town. Only a small number of the reincarnate lamas survived in Tibet. But they were the essence of the church, for many Tibetans the most important leaders, the ones they rallied to.

"We can't let them do what they did to the Panchen Lama," a voice said from behind them. Jowa stood there, still looking haggard. But his eyes had fire in them.

Shan nodded sadly. The Tenth Panchen Lama, the highest reincarnate lama next to the Dalai Lama, the traditional head of Tashilhunpo gompa, had at first chosen to cooperate with Beijing, hoping to avoid bloodshed, accepting assurances that Beijing would preserve his gompa and the Buddhist traditions of Tibet. After he had been taken to live in Beijing, the army had imprisoned the four thousand monks of his gompa. Following years of indoctrination, he had been deemed sufficiently subdued to return to Tibet, but at a festival in 1964 he had discarded his speech prepared by the Bureau of Religious Affairs and shouted out his support for Tibetan independence before an audience of thousands. For that one act of defiance he had been sent back to Beijing in chains. After his death, under highly suspicious circumstances, the Bureau of Religious Affairs announced that it had found his reincarnation in the son of two Party members and took the boy into its custody for special education. The Buddhists, with the help of the Dalai Lama in India, using ages old divination practices, had separately identified a Tibetan boy as the rightful Panchen Lama, but the boy had been abducted by the government and not seen for years.

"I heard about a speech in Lhasa," Lokesh said with pain in his voice. "The government said it had been too tolerant, that they won't allow any more incarnations of senior lamas to be recognized. That there will be no more Dalai Lama after the fourteenth dies."

Gendun sighed. "Khitai was found when he was three years old," he explained, "by elders of his sect." There were special procedures, Shan knew, used for the identification of reincarnate lamas, each different according to the traditions of the sect. "The boy identified things from the lama's prior incarnations. The oracle lake gave a sign in the shape of his initials. He bore the birthmark, on his left calf. It was decided immediately that he must be kept hidden until he could assume the full role of the Yakde."

A birthmark. The dead boys had all had their pant leg sliced open.

"Lau, a nun from his order, had already been sent to make a place for the reincarnation when he was identified, in the north, in the borderlands. Then when the time came, Bajys accompanied him, because he had been a novice and because he came from a dropka family and knew the ways of herders."

Lau's records, Shan recalled, had been in order for the past ten years. It had all been for the boy lama, her settling in Yoktian, her election to the Agricultural Council, her adoption of the zheli. Not a mere ploy, for he knew she had loved the zheli, but an elaborate way to create a hiding place while still remaining true. "But Lokesh said he played with-"

Gendun smiled at the old man. "As Lokesh said, they used to play together. The one called Khitai was in the boy age of the last incarnation then, and Lokesh knew him in the boy age, the last time. Khitai would recognize him and know a friend had arrived." Gendun looked out the portal. "Or, if the worst happened, we would collect his artifacts, his special possessions."

Shan remembered Lokesh with Khitai's possessions at the boy's grave, staring at them as if they spoke to him.

"If Beijing understood," Lokesh said in a pained voice, "it would try to seize them, to forestall the selection process."

A chill crept down Shan's spine. "But you didn't find everything," he said to Lokesh, "You didn't find the Jade Basket."

Lokesh sighed. "No. We have the silver cup that my friend the Ninth used to drink from the oracle lake at their oldest gompa. We have the pen case. But not the most important of all, his gau. We need the gau. It is very old. It has always belonged to the Yakde Lama."

"The killer has it now," Shan said in an agonized voice. "He found Khitai." He stared down into his hands. "So I will find the killer, and I will get the gau."

"You'll never beat the government," Jowa said.

Shan looked up at him. "Is that what you think, that it's all of them together?"

"Sure. That's the way they work. Always directed from Beijing."

"I don't know," Shan said. "Some things have changed."

Jowa frowned and slowly shook his head.

Lokesh stood and placed his hands over the brazier, breathing in the fragrant juniper smoke. "So we must go," he announced, with a strange determination in his voice.

"Yes," sighed Gendun, rising from the table. He swayed, unsteady on his feet. "Perhaps I will rest a few hours first."

Shan looked with new hope at his friends. "You can be back in Lhadrung in a few days."

Jowa nodded heavily. "I will get a truck."

The two Tibetans looked at Shan with obvious bemusement in their eyes. "Not Lhadrung," Gendun said. "Down there, in the world. That is where we are needed."

"No, Rinpoche," Shan said in sudden alarm. "Please."

"Khitai is dead," Gendun said calmly, "and there is a boy spirit, undeveloped, unprepared, still trying to understand what happened. He needs our help. No one read him the Bardo rites. He will be confused. Even for a tulku it can be difficult if he had not obtained full mindfulness in his last incarnation. We will help him. A spirit who is uncertain may look for familiar faces. We must try to help him into the next life. And you must find the Jade Basket."

"Please," Shan asked in a desperate, pleading voice and stood, stepping toward Gendun. "What could you do? Nothing. The knobs are down there. The Brigade is down there. The prosecutor is down there. I can only find the gau if you go to shelter."

"Shelter?" Gendun said slowly, as if unfamiliar with the word. "We can go to the grave of the boy. We can pray and meditate. Then we will follow the signs."

You investigate in your world, Gendun was saying, and we will investigate in ours.

"No," Shan pleaded, his voice heavy with dread. "The place of his grave is watched by the prosecutor. You have no protection. No papers. You could never survive."

Gendun offered a patient smile. "We have our faith. We have the Compassionate Buddha."

Shan looked at Gendun, the reclusive monk who led a fragile existence in the cave hermitage of Lhadrung, who had never been in a truck until two weeks earlier, who did not know guns and helicopters and the electric cattle prods favored by knob interrogators. He stepped to the brazier beside Lokesh. "I promise you. If you return to the safety of Lhadrung, I will find the killer. I will bring back the Jade Basket, if I have to go to Beijing to do it. Get rest tonight and then go back to the fragrant room until Jowa arranges a truck. You can go home."

"Get rest tonight," Lokesh agreed with a nod. "Home would be good," he added in a contemplative tone. Gendun took Shan's hand and squeezed it, then the two Tibetans let Shan lead them to pallets in the nearest meditation cell.

But when morning came Jowa sat at the table, his face desolate. Bajys was running up and down the tunnels desperately calling out their names, his woeful voice echoing into the chamber. But they were not to be found. Gendun and Lokesh had left in the night. They had gone down to the world.

Chapter Fifteen

Shan sat on the sentinel stone in a wind heavy with the scent of snow, letting it churn about him. Not just Gendun was lost this time but Lokesh too, wandering out into a world gone mad. He had left Jowa staring out of one of the portals with a blank expression. Bajys was walking about short of breath, as though constantly sobbing. Go back to the cell, Shan had told himself, sit with the ancient bow until you find a target again. But his mind had been too clouded, and he had climbed to the ancient sentinel post as the tide of sunlight swept over the vast open plain, sometimes watching for a glimpse of two figures in the distance, sometimes looking to the fast moving clouds for answers.

A snow squall burst upon him, suddenly engulfing him in a fury of whiteness. He did not move, ignoring the cold, ignoring the particles that bit into his face. Perhaps it wasn't a storm, he told himself, perhaps he was looking inside his mind. It was all that he felt now. Confusion. A swirl of conflicting thoughts. Adrift between worlds. The coldness of death. Even if Khitai were the Tenth Yakde, why did he have to be killed so urgently? Why would the knobs let one of their officers be killed without reprisals? What was the nameless American doing at Glory Camp? Why had Sui wanted to arrest Lokesh, but only once he was away from Director Ko? Had they discovered the old waterkeeper? Was the serene teacher of the boy lama being tortured at this very moment? A patch of sky appeared through the snow, then as suddenly as the squall had started, it stopped. And in the next moment he realized that he had at least one more piece of the puzzle and that he must act on it. He had been looking for clues in the world of Lau and the zheli boys. Now he had to look for clues in the world of the Yakde Lama.

When he went below Bajys had Jowa's coat on the table, brushing it with a tuft of horsehair, his hands trembling as he worked. Jowa sat nearby, staring at a map.

"There were gompas," Shan said to Bajys. "Gendun said there were still gompas of the Yakde. He said they grew out of the empire period, when there were armies that moved through this area. Meaning, maybe there were gompas established along the old empire routes here. How far is the nearest?"

Bajys just shook his head.

"If Khitai had lived," Shan pressed, "if you had known Lau was dead and had to take Khitai somewhere, where would you have gone?"

Bajys kept brushing. "Secret places," he said, looking over his shoulder toward the portals as if someone was hovering outside to overhear. "Lau knew them," he said, then glanced at Shan apologetically. "She was never going to die," he added in hollow tone.

Jowa looked at Bajys with a strange, expectant expression, as if at any moment to speak to him, to offer the words that might finally bring the tormented man's soul into balance. Or maybe just to embrace him, to comfort him and assure him that he had done no wrong.

"You mean, unregistered places," Shan suggested. No gompa was permitted to function unless licensed by the Bureau of Religious Affairs.

"I know about the Yakde gompas. I've read about them," Jowa said with a meaningful glance toward Shan. The purbas kept an ever-expanding chronicle of the atrocities committed by the Chinese, with copies maintained by purbas all over Tibet. "They were always in the remote places," Jowa said. "Out of touch with everything. Out of touch for years, sometimes. Places where no one would live, places where you would think no man could live. They were dying out, even when Religious Affairs started looking for them. Some were closed, their monks imprisoned. But some were too remote, too tiny for the government to worry about. The air force made bombing practice on three or four, didn't bother with the rest. Word was that in some of them disease swept through and killed all the monks."

"But Bajys," Shan said, putting his hand on the nervous man, guiding him gently onto the bench beside him. "They must have told you. A place to take Khitai in case of trouble, in emergency. A dropka, like you, could find places in the mountains."

Bayjs pressed his hand against his forehead, as if it hurt. "Lau. I was to go to Lau."

"Did she ever speak of another place? Maybe she went there herself sometimes. Maybe the waterkeeper went there."

"A diamond lake," Bajys said. "All I know is she went there for strength once, to a place with a diamond lake."

Jowa's head shot up. "There's a lake, a shrine lake, an oracle lake, a few miles from here. I saw it once from a distance, with an old hunter. He said it froze much later than others, that deities must live in it because it always shined like a diamond."

***

They walked in silence for hours, through the high barren landscape, wary of any sound, dashing for cover even at a sudden roar of wind, fearful that it could be a plane or helicopter. Their paths were the trails of wild goats, their landmarks distant peaks that Jowa frequently stopped to study, as if he were mentally triangulating their postion. The purba led them around a valley where a small herd of antelope ran, then passed over a saddle of rock and began climbing a long ridge, always climbing, jogging along the bare places without cover, stopping twice to add rocks to the cairns built at high points as offerings to the mountain deities. A raven flew over them for an hour, watching them closely, circling back, roosting from time to time as if waiting for them. Bajys, whom Shan always kept in front of him, stopped often to stare at the creature, as if somehow he recognized it.

They went higher, over another pass, then up a steep trail of switchbacks. Shan found himself gasping for oxygen for the first time since acclimating to the Tibetan altitude years earlier. They found a stream of blue glacier melt and drank long. Jowa remained squatting by the stream. "I was wondering," he said to Shan, "did you tell Lokesh where the waterkeeper is?"

Shan rose and looked at the purba. "He listened while I spoke about it," he recounted slowly, then saw the concern in Jowa's eyes and understood. Gendun and Lokesh might try to find the waterkeeper, a link to the lost boy. Shan closed his eyes and fought the image in his mind's eye. If the lama decided Glory Camp was where he needed to be, he would walk right up to the wire, walk right up to the knobs and Prosecutor Xu.

Before they left Bajys had collected a dozen stones and built a small cairn, a tribute to the deity who lived in the mountain they climbed. It was to gain merit, Shan realized, part of atoning for losing Khitai. Bajys started down the path as he finished, but Jowa and Shan lingered, each adding several stones himself, sharing, Shan knew, the same silent fear of Lokesh and Gendun being captured at Glory Camp.

The further they climbed, the greater became Shan's sense of entering a different world. Bajys seemed to sense it too. He hung back, trying to let Shan pass him, to let him linger behind, but Shan pushed him on. A snow squall passed over them, obscuring Jowa but leaving his tracks outlined in white for them to follow.

"If Jowa is wrong," Bajys said as Shan caught up with him, sounding suddenly very confident, "we will die in the cold that dwells this high." They had a single blanket for the three of them, only a small pouch of cold tsampa to eat, and nowhere was there sign of fuel for a fire.

Abruptly the sky cleared into a deep, brilliant cobalt.

Looking below, Shan saw that the snow had not stopped but that they had simply climbed above the storm.

They walked for another hour, over another ridge, then found Jowa waiting for them at the top of a small ledge that overlooked an extraordinary valley. They stood at the northern head of a mile-long expanse of gravel and dried grass that dropped between two long, massive rock walls with such perfect symmetry that they gave the impression of two monoliths that had once towered at the north end of the valley but that had been pushed over to shield the valley. Between them at the far end was a lake, still and clear, a piece of sky fallen to earth. The walls dropped at nearly identical angles toward the lake, each lined near its top with a tier of snow so perfectly straight that it seemed a baker had frosted them. Surprisingly, despite the cold and altitude, a few gnarled junipers grew at the edge of the water. And at the end of the valley, there was nothing but air. The world simply fell away past the strip of land that defined the end of the valley. In the far distance mountains could be seen, hugged by mist, but between the far peaks and the valley was only sky. Shan remembered stepping above the snow squall. It was as if they had arrived in a land that floated in the clouds.

"I thought this would be the place," Jowa said, with worry in his eyes. They would have no time to return to the shelter of Senge Drak before nightfall.

Shan moved to his side and looked down the face of the ledge they stood on. Three hundred feet below, past a series of ledges that jutted out like giant steps from the cliff face, there was a row of rocks. No, he saw, not a row, but a wall of rocks.

The silence was broken by a sudden hollow tapping sound from nearby, so loud it made him jump. A raven called as if in reply, and Shan looked up to see the large black bird land on a rock thirty feet away. Somehow he knew that it was the same bird that had followed them.

Jowa grabbed his arm, and Shan turned to follow his gaze toward Bajys, who had dropped to his knees by a flat rock that was immersed in the shadows. Bajys wore a look of wonder, the way Lokesh sometimes looked when his eyes saw between worlds. Shan took a hesitant step forward.

It was a rock, only a rock, or rather a large roundish boulder on top of a flat rock. But the rock had a smile on it.

They heard the hollow tapping again, louder, and it made Bajys crouch down, as if cowering. Shan drew closer, and the smile in the rock grew larger. Bajys wasn't cowering, he realized. The dropka was bowing.

A grey arm extended out of the boulder, holding the bottom of a short wooden staff, and as the base of the staff hit the rock they heard the tapping sound again. The raven spoke and hopped closer.

Shan knelt, then Jowa knelt, and as they watched, the boulder seemed to inch forward, its smile growing still bigger.

"Ai yi!" Bajys gasped.

The darkness above the smile stirred and two eyes appeared.

It was a man, an ancient man wrapped in a grey sheepskin cloak and a conical cap of the same material, shaped to cover the back of his neck and to hang low over his eyes, so that they were obscured when his head was bent. The eyes studied each of the three men in turn, sparkling with energy. The man tapped his staff again.

"After the snow my stick always rings," he said with amazement in his eyes, and he tapped it again for sheer pleasure. His voice was hoarse and slow, as if long out of practice. His skin was grey parchment, his fingers long and gnarled, as though made of jointed pebbles.

Shan looked at Bajys and Jowa. The Tibetans seemed overpowered by the old man.

The man's head drifted up and his eyes fluttered closed for a moment. "When the wind stops," he whispered, "listen to the water. You can hear it shimmering."

"We are looking for the gompa," Shan said with a quiver in his voice.

The man's head cocked to one side, and he laughed, a deep laugh that ended with a series of wheezing sounds. Then he abruptly rose, as if he had been pulled up by some unseen force. He stepped between Shan and Jowa and stopped, looking at the raven. The bird cocked its head at the man, turned toward the lake, and disappeared, not flying but jumping over the side of the ledge.

The man laughed again, stepped into a patch of shadow, and, incredibly, began to shrink.

Bajys gasped, then rose and stepped forward as if he might help the stranger. But the man had disappeared into the rock.

"A sorcerer," Bajys gasped.

"No," Shan said with slow realization. "Stairs."

They moved into the shadows and found a narrow set of steps, carved into the living rock and worn hollow in the center from centuries of use. Bajys darted forward and disappeared down into the shadows. Jowa and Shan exchanged an uneasy glance and followed.

It wasn't a cave they entered, as Shan had expected, but a dimly lit room of stone and mortar walls built against the cliff face. The light of a single butter lamp lit the room, below a long thangka of a brilliant blue Buddha. The Primordial Buddha, it was called– the Buddha of Pure Awareness. A brazier, laced with cobwebs, stood near the base of the rock steps. The wall opposite the rock face and the wall at the far end of the room each had a single heavy wooden door. Shan tried the nearest one. It opened slowly, with a groan of its iron hinges, into a chamber lit by a window that looked out over the valley.

From two wooden pegs driven into the mortar a rod was suspended, holding the remnants of an old jute sack over the stone window casement. There were cushions along the wall. On one cushion sat a small bow, like that he had used at Senge Drak. Though obscured with dust Shan could see that several cushions were made of silk, richly embroidered with shapes of conches, fish, lotus flowers, and other sacred symbols. It had the feel of a small dukhang, a monastic assembly hall, where lessons might have been given.

He stood silently as Jowa walked along the walls, feeling the reverence that permeated the chamber. "I think you have found it," Shan suggested. "One of the Yakde's gompas."

A small bronze Buddha, no more than eight inches high, had been placed on a stool near the window, facing the valley, as if to let him see the water that looked like sky. Or perhaps, Shan thought, so he could keep watch.

Jowa stood by the little Buddha. It, too, was covered with dust. He took the tail of his shirt and wiped clean not the Buddha but the stool around it, the way a monk would clean an altar without disturbing its sacred objects. When he was done he looked up at the door and back to Shan, both men realizing in the same moment that Bajys had not joined them.

They stepped back into the first chamber, then opened the second door. It opened silently into a dim passage. They followed it past half a dozen meditation cells and then descended another set of ancient stone stairs. The mountain, Shan realized, as he studied the steps and stone of the passage, did indeed descend in a series of huge stairlike ledges. What he had seen from the top had been the rock slab roofs of the structures built on those ledges.

A door at the bottom of the second set of stairs opened into a long passage, much warmer, its air hinting of incense and butter and the slightly acrid smell that came from braziers fueled by dried chips of animal dung. They passed more cells and opened a heavy timber door with ornate iron work, stepping into a large room that was brightly lit by two windows, one sealed with a frame of panes made of blown glass, uneven and bubbled, the other covered with a piece of transparent plastic sheeting that rattled in the wind.

There were half a dozen men in the room, all in faded maroon robes, seated in a circle around a large smoldering brazier. Several held the long rectangular leaves that came from pecha texts, and they appeared to have been reading to one another. One of them, now shorn of his cap and cloak, was the ancient man with the parchment complexion from above. Bajys, to Shan's surprise, was serving the monks tea, as if he were hosting them, as if he were a novice of the gompa, a familiar of the household.

Carpets, threadbare in spots, were laid on the floor, overlapping so that none of the stone floor was exposed. The walls were panelled in fragrant wood.

As Shan stepped forward, the men stared at him with wide-eyed expressions of curiosity. A bald man several years older than Shan but clearly the youngest of the group glanced at the back wall where clothing hung on pegs. The slight movement of his eyes confirmed Shan's suspicion that the monks were unlicensed. When Chinese came, the monks put on the clothes of peasants.

Jowa exchanged a glance with Shan. He had seen it too. The last gompa Shan had visited had a banner over its gate that read Buddhism Must Resonate with Chinese Socialism. It had been raised by the Democratic Management Committee of the gompa, the body appointed by the Bureau of Religious Affairs to supervise the gompa's affairs. Committee members, carefully screened by political officers before being appointed by the government, were responsible, among other things, for assuring that all monks signed certificates promising not to take part in political activity.

The tension in the room broke as Bajys stepped forward with tea for Shan and Jowa, and they silently sat with the monks in their circle. This gompa had no Democratic Management Committee, no political certificates, no licenses for its monks. If discovered by the government its residents would be arrested and sentenced to hard labor. Some monks, like Jowa, walked away from their gompas instead of signing political certificates and applying for Beijing's permission. Shan knew many who had signed, strong, devoted teachers who argued that a piece of Chinese paper made no difference, and others who insisted that no one could ever be the same after signing, that the act was like a dark stone cast into the waters of their serenity, rippling outward, changing forever the face of their inner god.

As he surveyed the circle of monks a realization warmed his heart. Although these monks had been warned about Chinese and wearing robes, he knew by looking in their faces that they had no first-hand experience with licenses or government bureaucrats who pressed monks to report what their companions prayed for. Only the youngest of the monks had hesitated and looked at the peasant clothing. The monks in the circle were like the untamed, feral animals of the changtang, untouched and pure. A species near extinction.

The monks sat quietly, smiling radiantly at their visitors. "Welcome to Raven's Nest gompa," the bald monk said.

Jowa, to Shan's surprise, spoke first. "We are sorry for the intrusion," he said. "We came about the Yakde Lama."

To a man, the monks nodded and kept smiling.

"He lived here," the bald monk said. "He's coming back."

Jowa threw a triumphant glance toward Shan, then looked back at the bald monk. "The boy Khitai? He lived here?"

The monks looked at each other in confusion.

"The Yakde," the bald monk said with a shrug, as if not understanding Jowa's questions. "He would sit and meditate in the middle of herds of wild antelope," the man said in a bright tone. "He wrote a teaching on it. We have it, in his own writing. That was the Second. The Fourth remembered and came to borrow it, and he took it to Lhasa to show the Dalai Lama."

The Second Yakde, Shan quickly calculated, would have lived at least three centuries earlier.

Jowa did not press. He did something truly remarkable. He looked at the bald man and smiled– a serene smile, a monk's smile.

"The Ninth," Shan said after a few moments. "Did the Ninth come here?"

"Once," the monk said. "He spent some months here and wrote a teaching about what we do here. The Souls of Changtang Mountains, he called it."

Shan's mind raced. He should ask about Lau, about the waterkeeper. But his heart had another question. "Did the Yakde go south, beyond Lhasa?" he heard himself ask. "To a place called Lhadrung?"