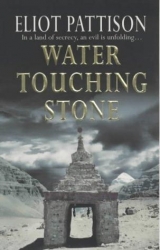

Текст книги "Water Touching Stone"

Автор книги: Eliot Pattison

Жанр:

Полицейские детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 22 (всего у книги 38 страниц)

"Three boys dead," Marco said gravely.

"Micah's out there," Abigail Deacon said, worry in her voice now.

"He's all right, Warp," her husband said reassuringly. "He's in the high mountains. Untouchable. Not long until the full moon, and we'll be together. A new performance."

Warp wrapped her arm around his leg. "You and your damned crickets," she said. "Micah's going to wind up with a bedroom full of insects when we go home."

"Good company. Smarter than fish," quipped Deacon. "Good joss."

His wife laughed, a soft infectious laugh. "My father kept crickets one summer," she said, "used them for fish bait." Deacon, who seemed to have heard the story before, lowered his hands over her face, and she playfully batted them away. "My mother hated them but she let him keep them so long as they were away from the house. One day he left a can of them in the bedroom, while he took a shower, and forgot them. A few days later he puts on his underwear and it falls to pieces. Every pair, full of holes eaten by the crickets. He never said anything. But he got rid of all the crickets that day."

"See?" Marco said with a laugh. "Good luck. Good luck for your mother."

They laughed. They all laughed, even Shan made a sound like a laugh. Marco told a story of how a pet squirrel had made a nest in his mother's only surviving dress from Russia, and they laughed again. Jakli explained how Nikki had once caught an albino mouse for her, and when he got to her camp it had given birth to five tiny pink mice in his pocket. Dr. Najan spoke of a pet pika that always chewed off the buttons of his mother's clothes and took them to his box as treasure.

As he listened a little lump grew in Shan's throat, and a stranger feeling in his heart. What was it? They were happy and he was happy for them. But there was something else. Something they were doing had reached a place inside, a hollow place, another of the chambers that had been unoccupied for so long he had forgotten how to open it. But once it had been full, once it had been overflowing. He recognized the place at last, in a pang of emotion. It was family, it was the way they spoke so openly and laughed so readily, the way Marco and the Americans and even Jakli were so familiar and confiding of the little things, the personal things. Long ago, Shan had shared it with his father and mother, but never with his wife, never with his son.

"How about you, Inspector?" Marco asked in a jovial tone. "Ever have a pet?"

It took a moment before he realized the Eluosi was speaking to him. Shan looked out over the dunes, mottled in evening shadow, like a rolling sea. It seemed like he spent a long time, exploring the forgotten chamber, but they all waited in silence.

"Not a pet," he heard himself say in a near whisper. "In the China of my boyhood you never had enough food to keep your own belly full. Pets never survived. But when I was young my father and I would go to the river and watch the world go by. In the fall farmers would bring ducks to market from far inland. They would clip the wings of the ducks, thousands of ducks, and herd them downriver like vast flocks of sheep, the shepherds in sampans wearing black shirts and straw hats. Once I cried because I realized all the ducks were going to be killed and eaten." He sighed and looked toward the stars. "My father said don't be sad, that for a duck, it was a grand adventure, to float hundreds of miles out into the world, that the ducks would have chosen the river even if they knew their fate. Then he looked all about, very serious, to be sure no one listened, and told me a big secret. That sometimes ducks escaped and made it all the way to the sea and became famous pirate ducks."

No one spoke. No one laughed. He glanced at Marco, who was just nodding toward the horizon, as if he knew all about pirate ducks.

"After that," Shan continued, "every time we went to the river we took paper and inkstones and brushes. We wrote poems sometimes, about the grandeur of the river and how the moon looked when it rose over the silver water. Sometimes I just wrote directions to the sea. Then we folded the paper into little boats and sailed them into the duck herds."

They watched the stars. After a few minutes Marco outlined with his finger the constellations and challenged the Americans to tell the English names. The Northern Bushel they instantly knew as the Big Dipper, and the White Tiger as Orion the Hunter. The game continued good-naturedly. The Porch Way was Cassiopeia, and the Azure Dragon, Sagittarius.

Lokesh wandered from the group and sat on the sand twenty feet away, facing the darkness. He seemed to be looking at something, or at least toward something. Shan considered the direction and noted the position of the small mountain they sat beside. His friend was looking toward the Well of Tears. Lokesh had heard lost souls there.

"Xu had a file on Americans," Shan said suddenly. He was reluctant to break the mood, but the words had to be spoken. Everyone seemed to freeze, and they all watched him intently now. "A list of visiting groups." He looked at Abigail Deacon. "She has your name."

She shrugged. "I was in a delegation. A group of professors, looking at the ruins of the Silk Road market towns. The Marco Polo tour, they called it."

"But only one name was circled on the list. Yours."

The American woman looked at him uncertainly, almost resentfully, as if Shan were accusing her.

"There could be a dozen reasons, Warp," her husband said. "Your flight connections were delayed."

"Sure," Dr. Najan confirmed. "They had to arrange a special car for you to catch up. That's when we first met, the day you caught up with us. Warp, she always wanted to do things not on the itinerary. Asked for a guide to take her to some of the old watch towers on the mountains. Asked for special food." He looked at Shan as if scolding him. "So they circle a name. Lots of reasons."

"Lots of reasons," Shan agreed woodenly. Good reasons. And bad reasons. He surveyed the team that lived in the little outpost. So far from the world, so absorbed in the grand mystery of their science, it would be easy to forget the bad reasons. The Public Security reasons. The Ministry of Justice reasons.

"The killer," Marco said. "He's hiding far away by now. With Sui murdered, he'll know the knobs will be angry as hornets."

"No," Shan said, and he pulled from his pocket the list of names that Jakli had retrieved from Lau's office. "He killed a third boy," he reminded them. "He has a plan." Shan handed the paper to Deacon, who produced a tiny flashlight. His wife held the paper as Deacon held the light and the others gathered around.

"Twenty-three names," Shan explained. "The zheli. The list is from the school records, the official roll of participants. Anyone could get it. You could print it from a government computer in Urumqi or Lhasa or Beijing if you wanted. Eleven girls. Twelve boys, nine left alive. First Suwan-" Shan pointed to the center of the list, then to two others. "Alta, and Kublai."

"But there's no logic, no way to know what the killer is thinking," Marco said.

"Wrong." Shan pulled a pencil from his pocket and reached for the paper, then handed pencil and paper to Jakli. "Eliminate the girls," he said.

She studied the paper and quickly drew lines through eleven names.

"Then Suwan," he said, and she put an X by the boy's name. "And the boy with the dropka parents who was killed-" Jakli made another mark. "And then Kublai." She made a third mark and returned the paper to the American woman.

The first X was on the center of the page. The next two were the top two names of boys.

"That's his great logic?" Marco asked skeptically, as if he thought little of Shan's discovery. "Just go down the list?"

"He targeted Suwan, and when Suwan proved not to have what he wanted he started from the top of the list."

Abigail Deacon gasped and grabbed her husband's leg tightly. "Micah!" she said in alarm, pointing to a name midway down the list. The fourth boy from the top. After Kublai came a boy named Batu, then Micah Karachuk.

"You can't run to him," Marco warned as he watched the Americans. "It may be what the knobs expect. They're watching everywhere. It must be why they haven't acted on Sui's murder, hoping you'll come out of hiding. You're too conspicuous. You'd be seen in the mountains, reported. Then Micah-" Marco shrugged. "Micah needs you to stay where you are."

Deacon nodded. "We made up the name," the American said in a near whisper as he stared at the list, then began to explain their decision to entrust their son to Lau. Soon after they had arrived in the desert it had become clear that their cavern at Sand Mountain was no place for a ten year old. He had met some of the zheli, had met Khitai, at a horse festival in the spring. Micah spoke Mandarin, as did most of the children, and was quickly picking up enough of the Turkic tongue to get by. He loved animals. The zheli was the perfect answer. He would be well protected, watched over by Lau and the nomads. "Besides," Deacon said, trying to lighten his wife's mood, "He's such a mischievous pup, the discipline of the sheep camps would be great for him. He loves it. Been with four different families so far."

"Lau knew this?" Shan asked.

"She suggested it. But kept it secret from the others. So Micah was just a Kazakh boy from a distant part of Xinjiang. Several of the children only spoke Mandarin, because they had been raised in government schools, so his not speaking the clan's tongue was not suspicious."

"So none of the children knew?" Shan asked.

"Not supposed to. But you know ten-year-old boys. Last month, Lau told us Micah had bragged about his parents, then at a class he handed around a jar of American peanut butter. We didn't know he had taken one. Then when I went to see him, he surprised me with three of his friends. Made me promise to come to some classes just before we left Xinjiang, to talk about our discoveries."

Shan stared at Deacon a moment. The Americans were planning to leave soon. Had the boys' killer learned this, and been forced into desperate action?

"He's made some good friends, better friends than in America," the boy's mother added. "Especially Khitai. Micah asked if Khitai could come to our moon festival, to hear the singers." There was no fear in her voice now, which comforted Shan. She had decided her son was safe.

"Stone Lake," Deacon said. "The next two classes are at Stone Lake. Lau always took the children there in the fall."

"If he comes," Jakli said. "Warnings have been going out. Some of the children may stay hidden in the mountains."

"The people he's with now," Deacon said, looking at his wife, "they are as hidden as hidden can be. Not a clan, just two men, a woman and two children. No assigned lands. No contact with the Brigade. The other children don't know where they are. Not even Lau knew all their hiding places. They just stay high up, until winter, roaming just below the ice fields. Lau said we shouldn't expect Micah to see us or anyone else, except on the class days."

"But the others," Jakli said in a forlorn voice. She read the next few names on the list. "They are in danger. The killer could be stalking them. Tonight."

The color had faded from the sky. A cricket sang from the rocks above. Lokesh took another cup of tea and sat, as if listening to something in the darkness. Then, from the edge of the little circle Lokesh spoke, unexpectedly, still looking out into the desert sky. "They say the Jade Basket can vanish, when evil draws near."

"What do you mean, Lokesh?" Jakli asked.

But even if the old Tibetan had been speaking to them a moment earlier, which was far from certain, he was conversing only with the stars now.

Shan realized that Marco had gone, then turned toward the entrance and saw him standing above, on a tall boulder that gave him a perch to see far out into the desert. And he was looking, looking hard. It was for Nikki, Shan realized, his son who was on caravan, smuggling goods across the border. Nikki, who was going to change Jakli's life forever. Shan saw that Jakli had noticed too. She followed Marco's gaze for a moment toward the darkness, then quickly turned back to the others.

"My cousins and the Maos won't find them all. We have to be there to warn them," she declared urgently. "They're supposed to be at Stone Lake in five days. Kaju is going there." She looked back at Shan. They had no vehicle, he realized. They were stranded in the desert.

"That Tibetan?" Najan asked. "He's one of them. Works for Ko. For the Poverty Scheme. Who best to trap the zheli than their own teacher?"

The words seemed to create a stillness in the air, like the calm Shan had felt before the horrible sand storm.

"No," Jakli said slowly. "The Brigade is only conducting business," she said uncertainly. "It has to be the knobs. Or Xu."

"Either way," Deacon said heavily, "the other boys have to be protected. They're in greater danger than Micah."

"A boy named Batu," Shan said toward the night sky. "Next on the list."

Marco appeared, his eyes still watching the desert. He poured himself a mug of tea, drained most of it in one gulp, then threw the remainder into the sand. "It's a clear night. With the stars out, we can navigate. I leave for the Kunlun in three hours. Sophie and I, we'll take you as far as town. The Maos are there, they can get you a truck."

"Then I suggest we get some sleep," Jakli said. She walked over and put her hand on Lokesh's shoulder. The old Tibetan turned his head, still wearing his distant expression, then rose and silently let her lead him inside.

Shan did not feel like sleeping. He had slept for two days already. He helped the others remove the cooking implements to one of the cells that had been converted to a pantry, then wandered along the murals on the walls. Lokesh was right, Shan felt it too. Never had he been anywhere where he felt so connected to the ancient world. It wasn't a quality of history he felt, nothing like the distance created by museum displays. It was a direct, visceral quality of continuity, of the great chain of life. No, perhaps it was only the chain of truth he sensed. Or maybe even simpler, a realization that people always had done good things, and it was only good things, not people, that endured.

But Shan was not sure what good things were anymore, or at least how he connected to good things. He was adrift, without answers to save the boys who were dying. His friends seemed to have secrets they could not share. His enemies seemed everywhere, yet impossible to find. His government would like nothing better than to put him behind prison walls again.

He found an oil lamp and wandered outside, climbing up the narrow trail that led to the top of the rocks. He lay back on a flat rock and mingled with the stars for several minutes, then lit the little lamp and took out his note pad and pencil.

Dear Father, he started. I have found a place from a different world, where I made a thousand-year-old friend. He should have been using an inkstone and brush and was shamed that he had only his pad and a stub of a pencil. Now I am supposed to provide everyone's answer, he wrote, but instead it feels like each person's tragedies and sorrows, now and in the future, cast a shadow and I attract the sorrows of all I meet, until I stand in the one place where all the shadows intersect, the darkest place of all.

I travel, but I have no destination. I have no family. I have no home to long for. I can only long for the longing. This is not what I expected my life to be, Father, when you and I wrote poems to the ducks.

Come closer, Father. Help me watch the stars.

He read it twice, then signed it. Xiao Shan. Little Shan, the way his father would have called him.

He would have liked to have bamboo splints and juniper, to make the kind of small fragrant fire that attracted spirits. But he had none. So he picked a few dried stems from the wiry bushes on top of the rock and arranged them in a small dense pile. He took a sheet of blank paper and folded it into an envelope, wrote his father's name on it, and set the letter on the twigs. It was a meager offering. He should have had rice paper, he should have spent an hour just practicing the rhythm of the ideograms before inscribing them in the bold flowing strokes his father had taught him. Forgive me, father, for these my shortcomings, he said in his heart, and lit the fire with the little lamp.

The ashes floated upward, toward the heavens. For a fleeting moment they drifted across the Northern Bushel, then they were gone.

After a long time Shan wandered back inside. The tunnels were silent. Even the camels were sleeping. With his little lamp held in front of him, he found the cell with the ancient pilgrim and sat beside him, gently pulling open the blanket that covered him so that Shan could see his hands and the worn spots at his knees that were the signs of a pilgrim. More than ever the man seemed to be asleep. Sometimes, when the light flickered, it seemed his mouth moved. He had been exposed in the karaburan that had almost killed Shan, the one that had made it impossible for Shan to leave for a new life. The scientists would take their samples from the pilgrim and he would be returned to the desert, perhaps to be exposed by another storm in a thousand years. A messenger. Or still a pilgrim, Gendun would have said, brought back to visit important places of virtue, to stir mindfulness in others, across time.

"My name is Shan Tao Yun," he said quietly to the silent figure. "I was born in Liaoning Province, near the sea, more than four decades ago." The words just came out, suddenly, without conscious effort. "When I was very small we made sweet rice cakes on festival days and took them to the temple. But sometimes I ate one when my parents weren't looking. They never found out." He spoke on, of memories that he thought he had lost until that instant, of his forgotten cousins and the way his mother sang opera songs to goats when they had been sent to a work camp. He smiled as he spoke, because the ancient man had come back and unlocked more doors in chambers he had forgotten how to visit.

The man's hands were held together, as if in prayer. Shan realized there was something between them, pressed together in the palms, with a protruding end barely visible. A stalk of something. A piece of grass, maybe. Shan leaned over with the lamp. As he did so he touched the arm and the top palm lifted fractionally. With a choke in his breath, Shan recognized it. A feather. A feather had been placed in the man's palms, a thousand years before.

He settled back, his heart racing. Then, with a slow, reverent motion he reached out and pulled it from the pilgrim's clasp far enough to see it in the lamplight. It was an owl feather, desiccated, its shaft bare for a quarter of its length, but still almost identical to the one in his gau, the one Gendun had given him before they had parted. He stared at it, overcome with wonder. Time passed, and still he stared. Not at the feather. At the man's face. At his long delicate fingers. The man had not been a shepherd. He had been an artist, or a teacher perhaps.

Finally, with utter confidence in the rightness of what he was doing, he lifted the feather from his gau, then carefully extracted the feather from the pilgrim's palms and inserted his own in its place. He placed the pilgrim's feather, the thousand-year-old feather, into his gau, then gently closed the man's hands, unprepared for the wave of emotion that swept over him. His own hands trembled. When they calmed he saw that they had come to rest on those of the pilgrim.

He pushed the rosary down the man's wrist, to be close to the fingers. Then, without knowing why, he cried.

Chapter Twelve

They rode urgently through the night, the three camels in single file as Sophie and Marco led the way toward Yoktian. Marco invited Shan to ride double behind him, and though the Eluosi was silent for the first two hours, he began speaking to Shan of camels and the beauty of the high lonely places he called his home. Just before dawn, as they crossed the Kashgar highway and Sophie settled into a trot for the final miles to Yoktian, Marco began singing loudly: old songs, Russian songs, songs he said were for drinking on long winter nights.

The sun was an hour over the horizon when they arrived at a series of low sheds by the river, a large complex of holding pens for livestock shaded by a row of tall poplar trees in the golden plumage of autumn. The pens near them were all empty, but five or six at the far end, a hundred yards away, were full of horses. The Kazakh herds were being collected. Marco tied the camels in the shadows of the first shed, then led Shan up a small knoll. They were on the outskirts of the town, less than two hundred feet from the main road leading to the town square.

Half an hour later, Shan, Jakli, and Lokesh approached the low mud-brick buildings of the hat factory. Workers were on benches, milling at the gate, and as they stepped into the compound, someone called Jakli's name. Akzu sat on a nearby bench, smoking with one of his sons. Their hands were stained purple.

"You're making hats?" Jakli blurted out.

"Of course. Wonderful hats," he said with a nod to Shan and Lokesh. "The best hats. Always wanted to make hats, niece," he said dryly, looking at his stained hands. "Thank you for the opportunity."

"But why-" Jakli began, but did not finish her sentence. She had realized, Shan knew, that they were to cover for her.

"No sense in taking undue risk, not so close to nadam. The manager here is a Kazakh. He said he won't cover up for anyone if he's asked, but as long as production is above quota not many questions get asked," Akzu explained, standing and stretching. "As long as the boot squads don't come." He looked at a woman who appeared on the steps of the main building, holding a clipboard. "There's worker attendance forms inside the door, niece. Go sign a few."

"But the zheli-" Jakli began.

Akzu held up a hand to cut her off and looked about before answering in a low voice. "The clan still searches for them. And for Malik. We can't find Malik. He was seen galloping down a highway yesterday, as if in pursuit of someone." He looked toward the southern horizon. "I go back into the mountains tonight. One of your cousins will stay here until nadam."

As Akzu spoke a low moan came from a nearby bench. An old man with a long drooping moustache sat and stared at a piece of paper in his hand.

"Been that way for hours," Akzu said. "He came here to ask the manager to explain where his sheep were. He thought it must be some kind of map or directions to a pasture."

"His sheep?" Shan asked.

"It's a share certificate in the Brigade company," Akzu explained in a bitter tone. "He surrendered his sheep to the Brigade, and all they gave him was a piece of paper. Sixty years with his herd and just a piece of paper."

As Jakli took a step toward the man as though to comfort him, Akzu pulled her arm and led her to the gate of the compound. Her eyes never left the mournful old herder.

Ten minutes later Shan and Jakli were at the school compound. There was a ragged broom leaning against the crumbling concrete gatepost. Lokesh picked it up.

"Cleanliness is an overlooked virtue," he said with a twinkle in his eye. Shan nodded and smiled. Lokesh meant he would wait, and watch, at the gate.

Shan and Jakli stood in the shadow of the empty entryway, checking for signs of knobs. Seeing none, they quickly moved down the empty corridor to Lau's office. They searched Lau's office again, looking for more information on the zheli. In her desk. In the computer. Under her desk drawers. Nothing. A number of the photographs had been pulled from the wall since their last visit, some ripped away, their remnants hanging loose. Someone else had come back to the office, searching. Looking for what? The photo of the Dalai Lama that Jakli had removed on their last visit? Jakli went outside, toward the class buildings, hoping to find children who might have word on the missing zheli. As she departed Shan saw that the light was on in the opposite office.

He stepped to the door, which was open a few inches, and looked at the little hand-lettered sign again. Religion is the Opiate of the Masses. He looked back. The sign would have been in front of Lau whenever she walked out her office. There were voices inside. As he pushed on the door, it swung open to reveal the short plump man he had met at the rice camp, Committee Chairman Hu, wearing a bulky, brown cardigan sweater. He was sitting sideways on his desk, facing the rear of his office as he spoke enthusiastically to a tall lean man who leaned against the rear window casement. Kaju Drogme.

They stopped speaking and looked at Shan as he took a step inside. The Han was holding something, explaining it to Kaju– a thin, sleek, grey box, curved at the front corners, with earphones hooked to its rear. The man raised his eyebrows toward Shan but his gleaming expression did not change.

Shan nodded at Hu. "Just looking at her office again," Shan said to the Committee Chairman.

Not only did Hu not seem surprised, he appeared to welcome the comment, as if it were an invitation. "A suicide, I told them," he said with an oddly bright tone. "Obviously it was a suicide. Disgraced from the loss of her council position. Facing retirement, with no prospects, no family."

Shan stepped closer to the man. The box was a music player of some kind. On the lid he saw a stylized logo for a Japanese company. A plastic bag with an instruction manual lay on the man's desk.

"Just the day before she did it, Comrade Ko came in and told her she would be welcome to move to Urumqi. Said there was a retirement complex, a high-rise building just for retired citizens. A number of heroes from the Revolution live there, they give speeches about the liberation battles every week. Said he was going to Urumqi and that he wanted her to go with him to see it. At Brigade expense." Hu shook his head, looking back and forth from Kaju to Shan. "But Lau wouldn't have it. Acted like Director Ko had kicked her. She sat down, out of breath. Too old-fashioned, she was. No flexibility." He lowered his voice and leaned toward Shan. "She had allowed herself to become isolated, cut off from the socialist fabric. A latent reactionary," he said in a knowing tone. "Go, I said, don't you recognize the offer? They are offering rehabilitation. I told them at the camp, wrote it all down for them."

Hu had become much more talkative now that he was out of the rice camp. He had a story now, and he had his job back. When Shan met him at Glory Camp he had said he had nothing to report about Lau. But Prosecutor Xu had kept him behind the wire, to think about things.

"You found a way to get out of Glory Camp," Shan observed. "Not really a place for a man like you."

Hu nodded energetically. "It was getting unbearable. Like an insane asylum with the patients taking over."

"What do you mean?"

"It was those men, the crazy ones who disrupted the camp."

"Disrupted?" Shan asked.

"One of the damned fools without thumbs. Or not him, really– he just translated."

Shan looked from Kaju to Hu in confusion.

"The senile old Xibo could make that man without thumbs understand him. Anyway, at three o'clock one morning they were all found sitting in a circle on the floor, the whole barracks, with the thumbless one and the Xibo sitting in front of them, chanting the political slogans they had been taught that day. When their officer stormed in and demanded an explanation, the old Xibo explained through the other. He said he was unfamiliar with the particular path to enlightenment being taught at the camp but that it was important to strive for perfection in its practice, since enlightenment must be the goal. Everyone in the barracks was different after that, obedient and polite, smiling like fools all the time. The officer was furious but the prisoners were doing nothing wrong. The guards kept the Xibo separated from the others after that, let him wander around alone. Mostly he sat at the bed of some Mongol boy who couldn't walk."

Shan sighed. He remembered the waterkeeper sitting alone at the flagpole. Maybe at least it might improve the chances for rescuing the waterkeeper, if the old man were able to freely move about the camp. He had vowed to himself that as soon as he knew all the boys were safe, he would return to Glory Camp and find a way out for the old Tibetan. Shan saw that Kaju was staring at the teacher with a puzzled expression.

"You mean there is a lama at the camp?" Kaju asked.

Hu laughed. "Not a damned lama. Just a crazy Xibo."

Kaju leaned forward and seemed about to correct the man, then shrugged and looked into his hands.

"What did you mean," Shan asked Hu, "that Ko was offering Lau rehabilitation?"

"People misunderstand Ko. He has the best of intentions. Comrade Director Ko was saying in his way that she was being forgiven for all the unauthorized teaching, for the misappropriations. Take the retirement flat, I told her. They'll have elevators there. Television."

"What kind of misappropriations?" Shan asked. Kaju still leaned against the window, gazing uncertainly at the Han teacher.

"Using Ministry of Education cars without permission. She took Ministry paper and pencils out of the school. Food from the school kitchen. Not to mention teaching unapproved curriculum or encouraging religious practices."

"Chairman Mao," Shan declared stiffly, "taught us to be vigilant. He warned us about religion."

"Exactly!" Hu agreed, and turned with a victorious smile toward Kaju.

"A good citizen like you would try to stop it, to do what you could," Shan suggested.

Hu nodded gravely. "I tried to warn her first. I've been teaching thirty-five years now. I went to university in Urumqi. It's not how things are done, I told her. She was never trained for teaching. What she did, it was never done that way."