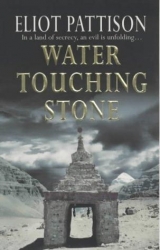

Текст книги "Water Touching Stone"

Автор книги: Eliot Pattison

Жанр:

Полицейские детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 38 страниц)

Eliot Pattison

Water Touching Stone

Chapter One

Everything in Tibet starts with the wind. It is the wind that offers up prayer flags to the heavens, the wind that brings cold and warmth and life-giving water to the land, the wind that gives movement to the mountains themselves as it sends the clouds careening down the ranges. As he looked out from his high ledge, Shan Tao Yun remembered a lama once suggesting to him that the human soul first became aware of itself in Tibet because the wind never stops pushing against its inhabitants, and it is in pushing back against the world that a soul is defined. After nearly four years in Tibet, Shan believed it. It was as though here, the highest of all lands, was where the planet, gasping and groaning, began its rotation, here was where it learned to move, here was where it was the most difficult for people to hold on.

There was an exercise for enlightenment Shan had learned from the lamas that was called scouring the wind. Extend your awareness into the air and float with it, become mindful of the world it carries and absorb its lessons. He and his companions had hours before darkness fell, before it was safe to travel again, and he sat cross-legged on his high perch and tried it now. Drying heather, Shan sensed. A hawk soaring high over the valley. The sweet, acrid scent of junipers, tinged with the coolness of snow. The distant chatter of ground squirrels on the rock-strewn slopes. And suddenly, before a spreading plume of dust in the north, a single desperate rider.

As Shan shielded his eyes to study the intruding figure, a sharp syllable of warning cracked through the air. He turned to see Jowa, his Tibetan guide, pointing to an old man in a broad-brimmed brown hat walking toward the edge of the ledge, staring up the valley.

"Lokesh!" Shan shouted and leapt to grab his old friend, who seemed not to notice when Shan grasped his arm. He was blinking and shaking his head, staring at the figure approaching from the far end of the valley.

"Is it real?" Lokesh asked in a tentative tone, as if uncertain of his senses. The day before, he had seen a giant turtle on the top of a hill, a sign of good luck. He had insisted that they take it an offering and apologized because it had turned back into a rock by the time they had reached it.

"It is of this world," Shan confirmed as he squinted toward the horizon.

"He's frightened," Jowa said behind them. "He keeps looking back." Shan turned and saw that the wiry Tibetan had found their battered pair of binoculars and was studying the figure through the lenses. "That horse is dead if he keeps it up." The Tibetan looked back to his companions and shook his head. "Someone is chasing him," he said in a worried tone as he handed Shan the glasses.

Shan saw that the rider was clad in a dark chuba, the heavy sheepskin robe worn by the dropka, the nomads who roamed the vast plateau of northwestern Tibet. Behind the dropka's horse the dust was so thick that Shan could see no sign of a pursuer. He scanned the landscape. Snowcapped peaks edged the clear cobalt sky for miles in three directions, towering over the rugged grass-covered hills that lined the opposite side of the valley. Neither the long plain below them, brown with autumn-dried grass, nor the narrow dirt track from which they had retreated at dawn, gave any sign of life other than the solitary rider.

Shan could see the man's arms now, flailing his reins against the horse's neck. He looked down at their battered old Jiefang cargo truck, hidden behind a large outcropping a hundred feet from the road, then handed back the binoculars and stepped into the shadow of the overhanging rock where they had taken shelter after their night's ride.

Ten feet away, where the shadow was darkest, Shan dropped to his knees. By the ashes of the small fire where they had roasted barley flour for their only hot meal of the day, a solitary stick of incense had been thrust into a tiny cairn of stones. A blanket of yak felt had been folded and laid on the ground, and on the blanket, sitting silently in the cross-legged lotus fashion, was a man in a maroon robe. He had close-cropped graying hair, and his thin face would have been called old by many, but Shan never thought of Gendun as old, just as he never thought of mountains as old.

The lama's eyes were mostly closed, in what for him passed as sleep. Gendun refused to rest during the night, while they traveled in the old truck, and he did not lie down in the daylight rest shifts taken by his three companions but only drifted off like this, after Lokesh had made sure he had eaten.

"Rinpoche," Shan whispered, using the form of address for a revered teacher. "We may have to leave," he said. "There is trouble."

Gendun gave no sign of hearing him.

Shan looked toward Jowa, who was using the binoculars again to survey the landscape beyond the rider, then turned back to Gendun, noting for the first time that the lama had arranged his fingers in a mudra, one of the hand shapes used to focus meditation, a symbol of reverence to the Buddha. He studied the lama's fingers a moment. The wrists were crossed, the palms held outward, with the little fingers linked to form the shape of a chain. Shan paused and stared at the hands. It was an unusual mudra, one he had never seen Gendun make. The Spirit Subduer, it was called. It chilled Shan for a moment, then he sighed and rose with a slight bow of his head, stepping back to Jowa's side.

The young Tibetan was looking up the slope above them, as though searching for a way to climb over the mountain. They both knew that there was probably only one reason the rider was so scared. Shan looked once more at the truck. Their only hope was that it would not be seen. It would be a bad finish, to be stopped here, high on the remote plateau, short of their destination. Not simply because of the suffering they would face from the Public Security Bureau, but because they would have failed Gendun and the other lamas who had sent them.

Lokesh sighed. "I thought it would be longer," he said, and touched the beads that hung from his belt. "That woman," he said absently, "she still has to be settled in."

Settled in. The words brought back to Shan how different they all were, how differently they seemed to view the strange task that had been set for them. Gendun had been with the lamas who had summoned Shan from his meditation cell in their mountain hermitage, seated on cushions around an eight-foot mandala that had just been completed that afternoon. Four monks had worked for six months on the delicate wheel of life, composed of hundreds of intricate figures created of colored sands. Fragrant juniper had been burning in a brazier, and dozens of butter lamps lit the chamber. A low rumble like distant thunder rose from a chamber below them, the sound of a huge prayer wheel that required two strong monks to turn it. For a quarter hour they had gazed in silent reverence at the mandala, then Gendun, the senior lama and Shan's principal teacher, had spoken.

"You are needed in the north," he had announced to Shan. "A woman named Lau has been killed. A teacher. And a lama is missing." Nothing more. The lamas were shy of reality. They knew to be wary of facts. Gendun had told him the essential truth of the event; for the lamas everything else would be mere rumor. What they had meant was that this lama and the dead woman with a Chinese name were vital to them, and it was for Shan to discover the other truths surrounding the killing and translate them for the lamas' world.

He had not known how far they would travel, and when he had arrived as instructed at the hidden door that led to the outside world, he had assumed that it would be to the north end of the Lhadrung valley, to the settlement nearest the hermitage. Nor had he realized that Gendun was to accompany him. Even when Gendun appeared at the door, Shan had thought it was to bid him well or offer details of his destination. He had even assumed that the canvas bag of supplies the lama had brought was for Shan. But then he had seen Gendun's feet. The lama had removed the sandals he always wore under his robe and replaced them with heavy lace-up work boots.

They had walked until dawn, when they had met Lokesh at the ancient rope bridge that spanned the gorge separating the hermitage from the rest of the world. Lokesh and Shan had embraced as old friends, for such they had become during their time together in Lhadrung's gulag labor camp, then the three had walked another hour until a truck had stopped for them. Shan had thought it was just a coincidence, just a favor from the driver. But the driver had been Jowa, and after Gendun had examined the vehicle with wide eyes, having never been so close to a modern machine, the lama had blessed first the truck, then Jowa, and climbed inside. Jowa had eyed Shan resentfully, then started the engine and driven for twelve hours straight. That had been six days earlier.

Shan had been confused from the outset, waiting each day for the clarification from Gendun that never came. But Lokesh had never seemed to doubt their purpose. For Lokesh their job was to resettle the dead woman, meaning that they must address her soul and assure that it was balanced and ready for rebirth. For Lokesh, the woman had to settle into her death the way the living, after a momentous change, had to settle into life. Not her death, really, for to Lokesh and Gendun death was only the reverse side of birth. But a death not properly prepared for, such as a sudden violent death, could make rebirth difficult. When a monk in their prison had been suddenly killed by falling rocks, Lokesh had carried on a vigil for ten days, to help the unprepared spirit through the period when it would discover it needed to seek rebirth.

Shan gazed toward the valley floor again. The rider continued his breakneck speed, bent low now, as if studying the ground.

Shan looked at his companions with grim frustration.

"Perhaps," Shan said to Jowa, "it is one of your friends." Jowa had been a monk once himself. But the Bureau of Religious Affairs had refused to give him a license to continue as a monk, and a hard shell had grown around the monk inside him. Jowa wasn't worried about resettling a soul. A teacher had been killed and a lama was missing, things that the Chinese did to Tibetans. Jowa had simply understood that they were being sent against an enemy. Shan studied him now as Jowa unconsciously rubbed the deep scar that ran from his left eye to the base of his jaw. Shan had known many such men during his years in Tibet. He knew the familiar hardness of the eyes and the way such men turned their heads when encountering a Chinese on the street. He knew the scars made by the Public Security troops, the knobs, who were fond of wielding whips of barbed wire against public protesters. The hard labor brigade from which Shan had been released four months earlier had been heavily populated by men like Jowa.

It had taken less than a day on the road from Lhadrung, however, for Shan to understand that the essential truth about Jowa was something else. As the former monk had stealthfully exchanged passwords with the horsemen who had taken them away from the Lhasa highway, Shan had realized that Jowa was a purba, a member of the secret Tibetan resistance, named for the ceremonial dagger of Buddhist ritual. He had replaced his monastic vow with another vow, a pledge to use up the rest of this incarnation in fighting to preserve Tibet.

"No, not one of us," Jowa replied curtly. "Not like that," he added enigmatically. "If it's soldiers I will go to the truck," he said in a low, urgent tone. "I will lead them away on a chase to the south. Gendun and Lokesh cannot move fast enough. Just climb higher and hide."

"No," Shan said, watching the rider. "We stay together."

Lokesh sat near the edge of the ledge and stretched, as if the approaching threat somehow relaxed him. He pulled his mala, his rosary, from his belt, and his fingers began reflexively to work the beads. "The two of you have strength," the old man said. "Gendun needs you, both of you. I will stay with the truck. I will tell the soldiers I am a smuggler and surrender."

"No," Shan repeated. "We stay together." As much as he needed Jowa for his wisdom of the real world, the world of knob checkpoints and army patrols, he needed Lokesh for his wisdom of the other world, the world the lamas lived in, for while they had to traverse Jowa's world to get to the place of death, once they arrived Shan knew he would be seeking answers in the lamas' world. Lokesh would have been a lama himself except that long ago, before the Chinese had invaded, he had been taken from his monastery as a novice to serve in the government of the Dalai Lama.

Shan watched Jowa remove the canvas bag that hung over his shoulder and his thick woolen vest, then wrap his hand around the pommel of the short blade that hung at his waist. Jowa would not speak about the priest within him, but at their campfires he sometimes spoke proudly about his bloodline that traced back to the khampas, the nomadic clans that tended herds in eastern Tibet, a people known for centuries as fearless warriors. Jowa no longer watched the rider but the cloud of dust behind him. Soldiers would have machine guns, but, like thousands of Tibetans before him, Jowa would rush them with only his blade if that was what it took to remain true.

"But the road," Shan said suddenly. "Why is he staying on the road?"

Jowa stepped to his side and slowly nodded his head. "You're right," he replied in a puzzled tone. "If someone chased one of the nomads, first thing he'd do, he'd get off the road." As he spoke, he swept his hand toward the wilderness that lay beyond the rough dirt track. They were in the wild, windblown changtang, the vast empty plateau that ranged for hundreds of miles across central and western Tibet, a land where the dropka had hidden themselves for centuries.

Lokesh cocked his head, then looked toward the opposite end of the valley, to the south. "He's not running from someone. He is running to someone."

They watched as the rider sped past the outcropping that hid their truck, reappeared, then abruptly reined in his horse. As the horse spun about in a slow circle, the dropka studied the road.

"I thought you hid the tire tracks," Shan said to Jowa.

"I did, for Chinese eyes."

The rider dismounted and led his mount toward the outcropping. Moments later he stood by their empty truck. After tying his horse to the bumper, he warily circled the vehicle, then climbed to the edge of the open cargo bay, his hand on one of the metal ribs designed to support a canvas cover over the bay. He stepped inside and lifted the lids of the barrels that stood there, then jumped out and studied the slope above him. Most of the slope was covered with loose scree, fragments of rock broken from the ledge above. Winding through it was the solitary goat path which they had climbed after leaving the truck at dawn.

"Sometimes the soldiers have Tibetan scouts," Jowa reminded Shan.

He touched Shan on the shoulder, motioning him into the deep shadow of the overhanging rock.

The dropka began climbing the path at a fast trot. Shan fought the temptation to pull Gendun to his feet, to scale the ridge and disappear with him. The others could explain themselves, they had identity papers. But no one could explain Shan or Gendun. Gendun, who had lived so hidden from the rest of the world that Shan had been the first Chinese he ever met, had no official identity. Shan, on the other hand, had suffered from too much official scrutiny. A former government investigator who had been exiled to slave labor in Tibet, his release from the gulag had been unofficial. If captured outside Lhadrung, he would be considered an escapee. Jowa pushed Shan against the rock in the darkest part of the shadow, beside Gendun, and waited in front of them, his hand on his blade again.

The man reached the ledge where they hid, took a few steps in the opposite direction, then turned and came straight toward them. When he reached the rock, he stepped toward the shadow and shielded his eyes to peer inside. "Are you there?" he called loudly, in a voice edged with fear. The man was of slight build, wearing a dirty fleece hat over a mop of black hair and a faded red shirt under his chuba. He twisted his head and squinted, as though still uncertain of what lurked within. Predators made lairs in such places, and so did the demons that lurked in mountains. He looked back toward the northern reach of the road, as if searching for something, then pressed his palms together in supplication and stepped into the darkness.

"We say prayers for you," he called out, still in his loud, frightened voice, then halted with a sigh of relief as Lokesh took a step forward. His mouth moved into a crooked shape that Shan thought at first was a smile, then he saw that the man was choking off a sob. "For your safe journey."

Lokesh was the most emotional Tibetan Shan had ever met, and he wore his emotions like other people wore clothes, in plain view, never trying to obscure them. In the prison barracks Shan had shared with Lokesh, one of the lamas had said Lokesh carried embers inside him, embers that flared up unexpectedly, fanned by a rush of emotion or sudden realization. When the embers flared, snippets of sound, in croaks and groans and even squeals, escaped him. The sound he made now was a long high-pitched moan, as if he had seen something in the man that scared him. As the sound came out he shook his hand in front of his chest, as though to deny something.

Jowa stepped beside Lokesh. "What do you want?" he demanded loudly, not bothering to hide his suspicion of the man. No one was to have known about their journey.

The man looked at the purba uncertainly, then took another step toward them. But as he did so Lokesh shifted to the side and the dropka was suddenly face to face with Shan, who stood in front of Gendun, hiding him from the man's view.

"Chinese!" he gasped in alarm.

"What do you want?" Jowa repeated, then stepped out into the sunlight, looking warily up and down the valley.

The herder followed Shan and Lokesh out of the shadows, then circled Shan once and looked back at Jowa. "You bring a Chinese to help our people?" he asked accusingly.

Lokesh put his hand on Shan's shoulder. "Shan Tao Yun was in prison," he said brightly, as if it were Shan's crowning achievement.

The anger in the man's eyes faded into despair. "Someone was coming, they said." His voice was nearly a whisper. "Someone to save us."

"But that's what our Shan does," Lokesh blurted out. "He saves people."

The man shrugged, not trying to conceal his disappointment. He looked up the valley, his right hand grasping a string of plastic beads hanging from his red waist sash. "It used to be, when trouble came," he said in a distant voice, as if no longer speaking to the three men, "we knew how to find a priest." He picked out a brilliant white cloud on the horizon and decided to address it. "We had a real priest once," he said to the cloud, "but the Chinese took him."

His expression was one Shan had seen on many faces since arriving in Tibet, a sad confusion about what outsiders had done to their world, a helplessness for which the proud, independent Tibetan spirit was ill-prepared. Shan followed the man's eyes as they turned back up the valley.

Someone was emerging from the dust cloud, a rider on a horse that appeared to be near collapse. The animal moved at a wobbling, uneven pace, as if dizzy with fatigue.

"When I was young," the man said, turning to Lokesh now, with a new, urgent tone, "there was a shaman who could take the life force of one to save another. Old people would do it sometimes, to save a sick child." He looked back forlornly at the approaching rider. "I would give mine, give it gladly, to save him. Can you do that?" he asked, stepping closer to study Lokesh's face. "You have the eyes of a priest."

"Why did you come?" Jowa asked again, but this time the harshness had left his voice.

The man reached inside his shirt and produced a yak-hair cord from which hung a silver gau, one of the small boxes used to carry a prayer close to the heart. He clamped both hands around the gau and looked back up the valley, not at the rider now but at the far ranges capped with snow. "They took my father to prison and he died. They put my mother in a town but gave her no food coupons to live on, and she starved to death." He spoke slowly, his eyes drifting from the mountains to the ground at his feet. "They said no medical help would be given to our children unless we took them to their clinic. So I take my daughter with a fever but they said the medicine was for sick Chinese children first, and she died. Then we found a boy and he had no one and we had no one, so we called him our son." A tear rolled down his cheek.

"We only wanted to live in peace with our son," he said, his voice barely audible above the wind. "But our old priest, he used to say it was a sin, to want something too much." He looked back toward the second rider, his face long and barren. "They said you were coming, to save the children."

A chill crept down Shan's spine as he heard the words. He looked at Lokesh, who seemed even more shaken by the man's announcement. The color was draining from the old man's face.

"We are going because of a woman named Lau," Shan replied softly.

"No," the dropka said with an unsettling certainty. "It is because of the children, to keep all the children from dying."

On the road below them, a hundred yards before the outcropping, the second horse staggered forward, then stopped. Its rider, wrapped in a heavy felt blanket, slumped in the saddle, then slowly fell to the ground.

The herder let out a sound that wasn't just a moan, nor just a cry of fear. It was a sound of raw, animal agony.

Shan began to run.

He ran in the shortest line toward the fallen rider, darting to where the path met the ledge, then leaping and stumbling down the loose scree of the slope, twice falling painfully on his knees among the rocks, then finally landing on all fours in the coarse grass where the valley floor began. As he rose he glanced over his shoulder. No one followed.

The exhausted horse stood quivering, its nose, edged with a froth of blood, nearly touching the ground beside a mound of black yak-hair felt. Shan slowly lifted an edge of the blanket and saw dozens of hair braids, a bead woven into the end of each. It was an old style for devout women, one hundred eight braids, one hundred eight beads, the number of beads in a mala. The woman was breathing shallowly. Her face was stained with dirt and tears. Her eyes, like those of the horse, were so overcome with exhaustion that they seemed not to notice Shan. Inside the blanket she had used as a cloak was another blanket, around a long bundle that lay across her legs.

He looked back. Jowa and Lokesh were slowly working their way down the path, Jowa leading the herdsman by hand, Lokesh thirty paces behind leading Gendun, as though both men were blind.

Shan raised the second blanket and froze. It was a boy, his face so battered and bruised that one eye was swollen shut. He slowly pulled the blanket away and gasped. Blood was everywhere, saturating the boy's shirt and pants, soaking the inside of the heavy felt.

He tried to lift the boy with the blanket, to take the weight from the woman, but the blanket was twisted in the reins. He tried to pull the reins away and found they were connected to the woman, tied around her forearm above her wrist, because her hand was useless. The wrist was an ugly purple color, and the hand hung at an unnatural angle.

As Shan lifted the boy out of the blanket and laid him on the dried grass, the boy's mouth contorted, but he made no sound. The boy, no more than ten years old, had been savagely mauled and slashed across the shoulder, through his shirt. He was conscious, and though he had to be in great pain, he lay still and silent, his one good eye watching as Shan examined him. The eye showed no fear, no anger, no pain. It was only sad– and confused, like the look on the herdsman's face.

The boy had fought back. His hands were cut deeply in the palms, wounds that could only have been made if the boy had grabbed at the thing that had slashed him. His shirt had been ripped open at the neck, the buttons torn away. Shan clenched his jaw so tightly it hurt. The boy had been stabbed lower on his body, a blow that had penetrated the ribs and left a long open gout of tissue that oozed dark blood. His pants too had been ripped in the fight, a long tear below the left knee. He was missing a shoe.

Shan looked back at the solitary, unblinking eye that stared at him from the ruin of the boy's face, but found no words to say. He gazed at his hands. They were covered with the boy's blood. Overcome for a moment with helplessness, he just watched the blood drip from his fingertips onto the blades of brown grass.

Lokesh appeared at Shan's side, carrying one of the drawstring sacks that contained their supplies. Producing a plastic water bottle from the bag, the old Tibetan held the water to the boy's lips and began to utter a low, singsong chant in syllables unfamiliar to Shan. Before he had been plucked from his gompa, his monastery, to serve the Dalai Lama, Lokesh had intended to take up medicine. He had apprenticed himself to a lama healer before being called to Lhasa, then continued his training during his decades in prison by ministering to prisoners, learning from the old healers who were sometimes thrown behind wire for encouraging citizens to cling to the traditional ways.

The old Tibetan nodded to the woman as he chanted, and gradually the words seemed to bring her back to awareness. When her eyes found their focus and she returned his gaze with a pained smile, Lokesh leaned toward Shan. "Her wrist is broken," he said in his quiet monk's voice. "She needs tea."

As Lokesh sat with the boy, Jowa settled Gendun into the grass by the truck, then brought a soot-covered pot and a piece of canvas stuffed with yak dung for a fire. When the pot was on the low blue flames, Lokesh looked up expectantly and Jowa motioned for Shan to help with the larger blanket. They untangled it from the woman, and Shan, following Jowa's example, secured the blanket with his feet so that, with both men holding the top corners of the long rectangle of felt, they created a windbreak. Lokesh needed still air for his diagnosis. As soon as the blanket was up he stopped his healing mantra and raised the boy's left hand in his own. He spread the three center fingers of his long boney hand along the wrist and closed his eyes, listening for more than a minute, then lowering the arm and repeating the process with the right arm as he tried to locate the twelve pulses on which diagnosis was based in Tibetan medicine. He finished by clasping the boy's earlobe with his fingers, closing his eyes again, and slowly nodding his head.

The boy just watched, without blinking, without speaking, without giving voice to the pain that surely wracked his body. The herdsman knelt silently beside him, his hands still tightly grasping his gau, tears rolling down his dark, leathery cheeks.

Lokesh finished and stared at the boy with a desolate expression. As if the motion were an afterthought, he slowly, stiffly raised the torn fabric of the boy's pants leg and looked at the skin underneath. The swing of the blade that had apparently slashed the fabric had not touched the skin.

"We can't stay in the open," Jowa warned, with nervous glances along the road.

"We could all have been killed," the dropka said in a hollow voice. "It was death on legs."

"You saw it?" Shan asked.

"I was bringing sheep down from the pasture. She was making camp. When I got to camp the dogs were barking on a ledge below. I followed the sound, with a torch. One of the dogs was dead, its brains scattered across a rock. Then I found the two of them. I thought they were dead too."

The woman's eyes opened as Jowa held a mug of tea in front of her. She raised her right hand with a grimace of pain. Jowa held the mug as she drank.

"Tujaychay," the woman said in a hoarse voice. Thank you. She took the mug with her good hand and drained its contents.

"The boy was bringing water from a spring down by the road," she said, her voice now stronger than her husband's. "He was late. I heard the sheep coming down the mountain. I needed to begin the cooking. Then the dogs started, the way they shout at a wolf." Jowa began fashioning a sling for her arm out of the canvas. "I ran. I saw it first from a ledge above, as it was attacking Alta. It was standing on its two rear legs. It had the skin of a leopard. I ran faster. I tripped and hit my head. I ran again. It turned as I came. Its front legs had paws like a man's hands, and one held a man's knife. But it dropped the knife and picked up a shiny stick, like a man's arm. It picked up the stick in both paws and hit me as I raised my hand. I fell and my hand hurt like it was in a fire. I crawled to the boy and covered him with my body. The thing came at us, waving the stick, but lightning called it back."

"Lightning?"

"In the north. A single lightning bolt. A message. It is the way that demons speak to each other," the woman said in a voice full of fear. "The thing looked at the lightning bolt and began backing away. Then I remember only blackness. When I awoke I thought we had both died and gone to one of the dark hells, but my husband was there and said it was just that the sun was gone."

"You saw its face?" asked Shan.

The woman's eyes were locked on the boy she had called Alta. She shook her head. "The thing had no face."

The announcement brought a low moan from Lokesh. Shan turned. The old Tibetan was holding the boy's wrist but gazing forlornly up the road, as if expecting the faceless demon to appear at any moment.