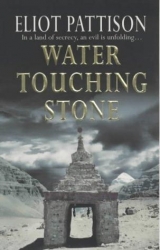

Текст книги "Water Touching Stone"

Автор книги: Eliot Pattison

Жанр:

Полицейские детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 16 (всего у книги 38 страниц)

"Him?" the Mao asked. "Been there all day. You think he's suffering? He's not suffering."

Shan extended the binoculars to Jakli. Was the man being punished? he wondered. Had he chosen to sit for hours in the sun and wind?

"It's nobody," the Mao said. "You couldn't recognize anyone from here anyway," he added and stepped away.

But Shan did recognize the man.

After ten feet the Mao turned. "You can't break them out," he called in a surly tone. "People get killed trying to break out," he warned and continued down the trail.

"I don't understand," Jakli said. "You know him?"

"You didn't know he spoke Tibetan, did you? You didn't know he used the cave."

She leaned forward with the binoculars, trying to see the man better.

"When he stood that day, did you see how tall he was?"

She lowered the glasses and searched his face, then drew in a sharp breath. "The waterkeeper," she gasped. Her lower lip went between her teeth and she raised the binoculars once again. "All those times," she whispered. "I could have asked for a blessing."

He looked at her, worried.

They walked back in silence and drove away.

As they climbed the long gravel-strewn slopes that led to the mountains, Jakli's mood lightened, and she spoke of familiar sights, pointing out where her clan had once camped, where she had once rescued a stranded lamb, where Lau had once shown her a nest of pikas. Once she stopped and pointed, almost breathless, toward movement on a hill in the distance. A small herd of wild horses. She climbed out and called something in the tongue of her clan, words lost in the wind. A horse prayer, she explained with a sheepish grin when she returned, to keep them from the Brigade.

They reached another road, which she eased onto warily, her eyes restlessly watching for approaching traffic, then slowly began climbing toward the snow-capped peaks as Shan continued to fade in and out of wakefulness. Once he awoke and the truck was stopped at the base of a huge grey cliff, with a meadow of asters on the opposite side of the road. Jakli was kneeling at the roadside, looking up at the tree-topped cliffs, holding a handful of flowers. He watched as she bowed her head and laid the flowers at the base of the cliff. When she returned he pretended to be still sleeping.

He faded back into slumber, and when he awoke it was late afternoon. They were driving in an unfamiliar landscape, amid mountains framed by a sky of deepening purple. He studied the ways the mountains folded into high mysterious valleys, the crags that spun upward as though they were giant hands pointing to heaven. He opened the window and tasted the chill rarefied air, fresh from icefields above. His memory did not know the terrain but his heart recognized it.

"How long have we been in Tibet?" he asked Jakli.

"The border isn't well defined here. Maybe five, ten miles ago."

"You must be exhausted. Let me drive."

"You don't know the way. Not much further."

They topped a high ridge and slowed to gaze on its fifty-mile view of the changtang plateau. In the far distance a large brown shape shifted and flowed across the grassland, a herd of wild animals. Antelopes perhaps, or even kiangs, the fleet mulelike creatures that still roamed the plateau. A few minutes later Jakli stopped the truck and stepped out into the wind. "I haven't been here in four years," she said. "There are no maps for it. Do you see it?"

"I've never been there," Shan said, and he turned to look toward the north. A pang of guilt swept through him. He had left the waterkeeper, and the zheli children, and Gendun.

"Senge Drak," Jakli explained. "It means lion rock. Shaped like a lion."

They studied the surrounding peaks, then climbed back inside, and Jakli eased the truck onto a narrow track that mounted the next ridge in a long, low ascent. At the top she stopped again and pointed. The mountain they were climbing unfolded to the south in a long U shape. They had reached the center of the ridge and were facing the opposite arm, a long bare ridge that ended in a huge cliff with the contours of a face. On top of the face were two outcroppings that might have been ears. Far below a small ridge jutted along the edge of the base, giving the appearance of a leg at rest.

In another hundred yards the track ended and Jakli parked the truck under a huge overhanging rock. Together they covered the truck with a dirty grey canvas she found in the cargo bay and began walking along the narrow goat path that traversed the steep slope. After a few steps she stopped and threw a pebble into the shadow of a second overhang. The pebble bounced back with a metallic clank. A second truck had been hidden at the head of the path.

Shan detected a subtle pattern of shadows on the face of the cliff as they approached it. Not all the shadows were just clefts in the rock, some were openings, portals that had been cut out of the cliff-face. The Lion Rock, Shan realized, was an ancient fortress, one of the dzong that once guarded Tibet. The dzong had been built into the formation, utilizing the lines of the towering rock to blend with the mountain, which commanded a view far out into the changtang and the pass through the Kunlun.

"It was so far away from the heart of Tibet that the government overlooked it," Jakli explained. "Or maybe the PLA just didn't think it worth bothering with. Couldn't be bombed from the air like most of the dzong. And it had been abandoned for centuries. No invaders would come from this direction. No meaningful armed resistance could be mounted from it. It doesn't stand in the way of anything."

They hiked to the end of the path as the remaining daylight quickly faded. Jakli paused to gaze at the last blush of crimson to the west, as if sending a silent prayer that way, then led Shan into a darker patch of shadow that was the entrance to the dzong. Following the dim light of butter lamps, placed at long intervals along an entry corridor, they arrived at a narrow door of heavy hand-hewn timber. As Jakli pushed it open, its iron hinges groaned loudly.

"Their alarm system," she said as she bent and led Shan through the door. Not just an alarm system, Shan saw, as he studied the door. It was so low that most of those entering would need to bow their heads, exposing their necks to a defender's blow, and so narrow that no more than one intruder could enter at a time. In an age when soldiers fought with swords and arrows, one or two defenders could hold off a small army at such an entrance. Jakli put a restraining hand on his arm after two steps. They would wait in the room.

The empty chamber was perhaps forty feet wide, the far side lit by a dozen butter lamps on a long table of hand-hewn timbers. To the right the wall sloped with the natural curve of the rock, as if the room had once been a natural cave that had been expanded. The wall beyond the table was hung with old carpets, which were slowly moving. From the draft that flickered the lamps Shan surmised that the carpets covered openings to the outside, the portals he had seen from the path.

He walked slowly along the hanging carpets. Some weren't just carpets, he discovered, they were thangkas depicting scenes of life in a monastery. The hangings by the portals were nearly threadbare, eroded by the wind. In one space a simple black felt blanket had been hung. Suddenly the hairs on Shan's neck moved. Someone was watching, from the other end of the room. Seeing nothing but shadow he lifted a lamp and ventured toward the darkness.

After five steps he froze. Two huge unblinking eyes stared back at him, level with his own. The serene head of the figure was slightly cocked, as if in inquiry, and one of its hands clutched a bell. It was a seated Buddha, carved so as to appear to be rising out of the living rock, so that although the head was nearly complete in circumference, at the bottom, where its legs were folded into the robe, the remarkable Buddha was little more than a bas-relief.

As he approached he saw that the rock on which the Buddha sat had been sculpted to simulate an altar, on which the figure seemed to be resting. On either side large niches were carved to receive offerings, their tops coated with the black soot of torma offerings, the butter figures that were burned on festival days.

Jakli stepped past him and placed a lamp in one of the niches. "The soldiers who built this place," she explained, "they were from the Tibetan empire period. Warrior monks. Sometimes they fought under the same lamas who led them in worship. We found an old writing about life at Senge Drak." She raised her hand to the head of the Buddha as she spoke, not touching it but following the gentle contours of its face with her fingers. "The monks were fabulous archers. They would not practice like others by shooting birds or deer or other living creatures, for they believed in the sanctity of life. So the archers would stand at the open portals and their teachers would drop paper birds into the wind for them to shoot."

"If all armies were like that," a familiar voice added, "war would be obsolete."

Shan turned. It was Lokesh, wearing his crooked grin. His eyes twinkled and he stepped forward to embrace Shan.

"But not every army shoots only paper birds," said another figure, emerging from the shadows as he spoke. Jowa. He seemed less happy to see Shan.

Lokesh winced, as though disappointed at Jowa for intruding.

"Are they here?" Jakli asked abruptly. "Did they come to celebrate while everyone pays the penalty down below?"

Jowa looked at her in confusion and seemed about to ask her a question when another figure emerged from the shadows. It was Fat Mao. Jakli bolted across the room, launching into a tirade in their Turkic tongue, raising her hands, not to strike him but to pound the air in front of the startled Uighur.

"Sui was a son of a bitch working for a bigger son of a bitch," Fat Mao said in Mandarin, and stepped closer to Shan and Jowa, as if he needed protection. Shan studied the Uighur. He seemed exhausted, and his clothes were soiled and torn in places. He had been traveling too. Perhaps fleeing. "He deserved to die. But I didn't kill him."

"Maybe not you," Jakli snapped, "but the other Maos. At the worst possible time. You're not warriors, you're just predators. Make a kill and run away. Let everyone else pay for it-" Her voice choked with emotion.

"It was not a Mao," Fat Mao insisted.

"You don't know that," Jakli shot back.

"I know it," the Uighur said. "If it happens in Yoktian County, I know it. Sui was being watched, whenever possible. But no one– no one of us– killed him. I know what you think. The knobs will think the same thing."

"Saving Red Stone clan. Finding Lau's killer, the killer of the children-" She stopped as if about to add to the list, but did not. "Impossible now."

Was that why? Shan wondered. Had someone killed Sui to distract the knobs from something, or, knowing how the knobs would react, to keep their little group from proceeding with their own investigation of Lau's disappearance?

Someone else stirred in the darkness. A short, slender figure appeared, carrying bowls on a wooden plank. "Jah," he announced in Tibetan. Tea. It was Bajys. Not the terrified, ranting Bajys, but another Bajys, or the beginning of another Bajys, for he still had the hollowness, the emptiness in his face that Shan had seen at Lau's cave. As Shan accepted the bowl from Bajys, he saw that the man's hand was steady, but there was a tremble in his eyes.

Jowa took a bowl and sat on the table, away from them, drawing a paper from his pocket to read, as if uninterested in further conversation.

Shan felt a tug at his sleeve. "The Maos must know something, if you were watching Sui," he said to Fat Mao. He turned and saw Lokesh beside him, pulling his sleeve, urging him toward the shadows.

"The first man to find the body was a Uighur truck driver," Fat Mao explained. "Driving alone with a load of wool for Kashgar. Sui's body was propped up against a rock at the side of the road."

"The killer made no attempt to hide it?"

"More like an attempt to make it conspicuous. The trucker saw him clearly in his headlights, thought he was sick or hurt, so he stopped. But Sui was shot through his heart. Twice. A quick death."

"You mean the body was arranged afterward."

"Exactly. In the sand beside the body a finger had written lung ma. No way Sui wrote it. He would have dropped like a stone."

"The knobs found him like that?"

"Not like that," Mao said. "The driver wasn't sure what to do, wasn't sure who Sui was."

"Sui was a knob. Everyone knows the uniform."

Fat Mao shook his head. "Sui wasn't in uniform." He looked from Shan to Jakli, letting the words sink in. "But Sui had a pistol in his belt. And then the next person on the road helped."

"Someone who knew Sui?" Shan asked. He turned toward the shadows. Lokesh had disappeared.

"Someone who was looking for Sui. Who erased the words in the sand. A Mao. He was going to hide the body, but there was no time because of traffic coming on the highway. All he could do was put Sui behind some rocks."

"You mean a Mao was following Sui?" Shan asked.

The Uighur nodded. "One of us had been watching Sui but lost him in Yoktian. Sui was to meet Prosecutor Xu at Glory Camp, so the follower drove in that direction."

Fat Mao stared at Jakli with a grim expression. Perhaps Xu had decided to meet Sui early, on the highway, to dispose of him for some reason.

"Sui's pistol," Shan asked, "what type?" The knob had died with his pistol in his belt, as though surprised by his killer.

"Not official. Small caliber, like a target gun."

"The size of the bullets used on Lau and Suwan, at the Red Stone camp," Shan sighed. Jakli sat down heavily at the table. "What happened? Why were you following Sui?"

"When the trucker understood who Sui was, he had no interest in staying. He drove away. After he spat on the body."

"Thank you," Shan murmured, "for that important detail."

Fat Mao shrugged. "We were watching because that's what we do, whenever we can. To warn people. To learn things." He pressed the heel of his hand against his temple. The Uighur's head was hurting, Shan realized. He wasn't used to the altitude.

"The Poverty Eradication Scheme," Jakli said. Her words brought a look of reproach from Fat Mao, but she did not stop. "Public Security is involved somehow. Sui came that day at the garage, when Ko was there for inventory."

"You mean Sui was working with the Brigade?" Shan asked.

The Uighur sat at the table, elbows on the table, and lowered his head into his hands.

"Probably," Jakli said. "Maybe just to make sure there's no dissension, make sure the clans get moved when they've been told to move, make sure no one evades the scheme."

"It was Sui who said the Brigade was going to collect all the wild horses," Shan reminded her.

Fat Mao raised his head. "Sui was following Director Ko," he announced.

"You mean, to Glory Camp?" Shan asked.

"I mean, to lots of places. For the past three weeks, at least. Like Ko was under suspicion by the Bureau." He pressed his hand to his temple again, then shifted on the bench and lay down upon it.

Shan looked about. Lokesh had not returned. Bajys had disappeared as well. He took a step into the shadows and discerned the outline of a doorway. He stepped through it into another tunnel, lit by small lamps. After thirty feet he stopped, confused by a new sensation. Not really a sensation, but a beginning of awareness, a glimmer of realization. He steadied himself with a hand on the rock wall, closed his eyes a moment, then suddenly opened them and began to run.

After a hundred feet, the corridor divided into two passages in front of a large wood pedestal holding a three-foot-high prayer wheel. Without hesitation Shan followed the left tunnel and came to a timbered door. The door was open far enough for him to see a square chamber of perhaps thirty feet to the side, softly lit by a ring of butter lamps in the center. It was a soft, silent room, lined entirely– floor, walls, and ceiling– with planks of fragrant wood. It was the kind of chamber built in temples to hold treasure. Shan stepped inside.

Lokesh was sitting near the lamps beside a man in a monk's robe, who was settled in the lotus position, his elbows on his knees, his fingers spread out to support his bowed head. Shan struggled to calm his racing heart. It was Gendun.

Shan joined the two Tibetans by the circle of light and sat silently, breathing in the scent of the old wood. He picked a flame and stared into it, seeking to focus himself, to cleanse his mind for Gendun. If what you selected was pure enough, absolute enough, you could immerse yourself in it; it could become your shield from distraction. Anything could work– a ball of mud, a drop of blood, a tiny heather flower– as long as it was pure.

"I met a hermit once," said a voice that drifted into his consciousness. "He claimed to have been reincarnated from a juniper tree. He said he could hear wood speak." The voice resonated in his heart and filled Shan with warmth. "He said we were all trees once in the past. I said I didn't think so, that I was still striving to become a cedar."

Shan blinked away from the flame and looked up to Gendun's broad smile.

The lama pressed his palms together over his heart in greeting, then stretched out his palms, forearms extended from his knees. It was his way of embracing Shan.

"Rinpoche," Shan said slowly. "We have come far from your mountain at Lhadrung."

"As long as I have a mountain to sit inside of," Gendun said, "there will be my home." His voice sounded like sand falling on a smooth rock.

Shan smiled. Gendun had meditated for so many years inside his rock hermitage that all those who knew him believed he could sense the life force of mountains.

"Have you been well?" he asked Shan.

"I have been confused."

Gendun smiled. "So have I, my friend." He fell silent again, but his smile did not fade as he looked from Shan to Lokesh.

"We thought those men took you that night," Shan said.

"The mountains here," Gendun said with a tone of wonder. "They have a different voice. Have you noticed? My eyes see them as a stranger, but in my heart I know them, from all those years ago."

Shan could only smile in reply. "Have you been here all these days, Rinpoche?" he asked after a moment.

"He left the truck when the Brigade stopped us," someone replied from behind him. Shan turned to see Jowa in the doorway.

"I came two days later," another voice said, and the youthful purba who had driven the truck away after they had met the Kazakhs appeared. The young Tibetan stepped past Jowa and into the room, his eyes wide as he looked at Gendun. "Just sitting right here, alone. He wouldn't leave."

Jowa lingered at the door, as if reluctant to approach the lama.

"How far, from where we stopped on the road?" Shan asked.

"Fifteen, maybe twenty miles." The young Tibetan shook his head. "But Senge Drak is secret," he said in a tone that suggested a question, as if asking Shan to explain it. "He had never been here. There were no trails from where he left the road."

Gendun gave no sign of having heard the conversation. He had already explained it to Shan. The mountains had their own voices.

Shan looked at Jowa, not the young Tibetan. Jowa looked not just tired, but uncomfortable, as if Gendun, one of the holy men he fought for, somehow intimidated the purba.

"We have told him about the second boy," Lokesh said in a suddenly somber tone.

Told him what? Shan wanted to blurt out. How would Lokesh have described Suwan's murder? Another young soul has gone beyond sorrow, perhaps.

But then Gendun spoke. "Have you come far?" he asked Shan.

Feels like far, Shan almost said, thinking of the grave at Red Stone, Lau's cave, the rice camp, and Karachuk. Feels like I've traveled a year in the last four days. "I met Auntie Lau," he offered.

"Do you like her so far?" Gendun asked with twinkling eyes.

"I think she honored all the worlds she lived in."

As Gendun nodded he slowly opened and shut his eyes.

"And I met an old waterkeeper."

Gendun nodded again and made a tiny flicker with his eyebrow. Shan recognized his question. "He is still in this life," Shan said. "In prison, but not suffering." His eyes moved from Gendun to the flame of the nearest lamp. "I am going to get him released."

Some things are not real until they are said out loud. Gendun looked at him, but not as intensely as Shan looked at himself. The words, though unexpected, though unintentional, rang like a bell. It took only a moment for Shan to realize, as some unconscious part of him already had, that in the miasma of people and events he had encountered since arriving in Xinjiang the only certainty was that the waterkeeper, the old lama with whom he had spent no more than two minutes, had to be freed from prison. And Shan was the only one who could do it, for only Shan understood.

The bell in his mind rang again. It grew louder. Not a bell, he realized, but the delicate tingling of tsingha, the small circular brass chimes used in Tibetan temples.

Bajys appeared at the door, smiling shyly while he rang the tsingha twice more, as if just for the pleasure of doing so. "There is food," he announced and turned back down the tunnel.

They followed the sound of the chimes down the hall to another large room cut into the living rock, nearly as large as the entry chamber, with similar portals opening to the sky. Shan realized they were on the opposite side of the cliff face now, the other side of the lion's head. The room was brightly lit with kerosene lanterns and butter lamps, and beside a timber table a brazier burned, fueled by large chips of yak dung. Fat Mao and Jakli were already at the table with another Tibetan, a large man with a heavily scarred face, who greeted Jowa and the young purba with a familiar nod. Shan looked back at Fat Mao. He had traveled hard that day, ever since Sui had died. But doubtlessly he had other, easier, places to hide. He had rushed to Senge Drak to see the purbas.

Bajys waited until Gendun was seated at the center of the table, then retrieved a pot of barley porridge from the brazier. No one offered introductions.

As they ate, the three purbas and Fat Mao spoke in hushed tones about the death of Sui, and Shan explained the killing to Gendun.

"I am sorry a government man had to die. We must be hopeful for his soul," the lama said quietly.

Fat Mao reacted to the lama's words with an exaggerated wince. His gaze moved along the faces of the purbas as he shook his head, as though to express his frustration that they should have Gendun among them. "We should just be hopeful for all those who are going to suffer now. The innocents. The families. The old people. Hope they hide well. Hope the monster eats its fill quickly and moves on."

"The pain will come," Jowa agreed. "Which is why we are going home. When the jackal comes to eat the turtle, the turtle must go inside its shell. We must protect ourselves. We must protect Rinpoche."

The lama tilted his head toward Jowa. "I don't understand your word. Protect?"

"We can do more good alive, and free, in Lhadrung," Jowa said. "The danger will pass. If you wish to return when it is safe here again I promise I will bring you. In a month, maybe two."

Jakli pushed her bowl to the center of the table. "Somebody in the purbas or the Maos knows what happened to this knob Sui," she declared sharply. "There are only a few who would ever touch such a man. People move to the other side of the street when they see such a man approaching. They avert their eyes. Men like Sui are like the dragons that roamed the land in the lost ages, inflicting random terror. The people don't seek out dragons. There were only special soldiers, sanctified by priests, who fought dragons." She glanced at Shan. "Warrior monks. Only they dealt with dragons. And if in killing one dragon they provoked a whole nest of dragons they still stood between the dragons and the people."

A sneer rose on Fat Mao's face. "And who is fool enough to stand before these dragons? These are Beijing dragons. Cut off a head and two heads grow back."

"There is no magic weapon," Shan said in the silence that followed. "There is only the truth. Whoever killed Sui must accept responsibility for the action."

"You mean, go to the nest of dragons and be eaten," Fat Mao shot back.

"If that is what is necessary to protect the innocent."

Jowa stood with a sour expression and gestured for the other two purbas to join him. "We're leaving. All of us. My job is to keep us safe. All of us. That means all of us go back to Lhadrung. We're not going to die for someone else's fight. I fight for Tibet. I fight for Tibetans."

Gendun's eyes settled on Jowa. "It is only the chance of birth that made you Tibetan in this life," he said in a tentative tone, as if puzzled by the purba's words. "You may be Chinese in your next. You may have been Kazakh in your previous."

"It is enough, just to watch out for this life," Jowa said sharply, but as the words left his mouth regret was already in his eyes, as if he had forgotten whom he was addressing. "Rinpoche," he added in a low, awkward voice. His hand went to the dagger at his belt, not in a threatening way, but self-consciously, as if to hide the weapon.

Gendun frowned. A fresh silence descended on the room. The lama stood and filled everyone's tea mug. He moved to Jowa, who still stood, and slowly lifted the purba's hand and placed it, palm open, over his own heart. Shan had seen it before, among the more orthodox Buddhists. It was how some lamas conveyed truth to a student.

"We do not struggle for Tibet or Xinjiang or for any other lines on a map. We do not struggle for Tibetans or for Kazakhs. We struggle for those who love the god within and for those who can learn to do so." Gendun withdrew his hand and looked into Jowa's determined eyes, then into Shan's and Jakli's. He moved across the room and stood near one of the portals, where the covering had been tied back, and faced the open sky, the wind rustling his robe.

"If I had killed a man like Sui," Jowa said to Gendun's back, a pleading tone in his voice, "I would not hide. I would give them my head proudly. But it was not me, and so I will not offer my head." He looked toward the floor. Despair passed over his face, then his eyes grew hard again. "We have to return to Lhadrung. There are other fights to wage. Fights we have a chance of winning." His eyes shifted toward Shan, then he looked back at Gendun and hesitantly pulled a paper from his pocket, the one he had been reading earlier.

"And you," Jowa said to Shan, with an expression that seemed to mix resentment and pride, "you have been rescued. You have an appointment at the Nepal border." He sighed loudly and waved the paper toward Shan. "A UN inspection team got permission for a quick tour of gompas south of Lhasa. We have a way to get you across with them when they leave, and they will take you from there." He unfolded the paper and extended it toward Shan.

"You won," Jowa continued, a trace of bitterness in his voice. "A chance in a million. But we have only eight days to get you there. Barely enough time to make it." He looked about the room, surveying the faces of the Maos and Jakli, then back to Shan. "No need to worry about other people's business now."

Shan gazed at his companions. Jakli was smiling brightly at him. Lokesh was nodding. "It is everything you need," the old Tibetan said. Gendun just smiled at him.

"Our truck is at the head of the path," Jowa explained. "There are barrels in the back, and blankets, like before. Everyone goes, including Bajys. When the moon rises we will all go to the truck and sleep there tonight, and we will begin before dawn." He drained his cup of tea and looked at Shan as he laid the paper on the table. "If we see any dragons on the path we will be sure to wake you," he added in a taunting voice. Jowa's companions joined in his laughter and followed him out of the room.

Gendun wandered into the shadows of the corridor, followed a moment later by Bajys. Shan poured more tea for Jakli and Lokesh.

"I had a teacher once," Lokesh said after a moment. "He didn't believe that the human incarnation was particularly important in the chain of existence. He said humans come and go, they throw off faces all the time, that the whole purpose of humans was to keep virtue alive, to be a vessel for virtue. He said that if you lived enough lives that way, you became virtue, and then you had a chance at true enlightenment."

Jakli, Shan, and Fat Mao sat in silence, considering his words. Certainly Lokesh was right about one thing, Shan thought. Humans were throwing off faces all the time. Somehow life seemed even cheaper in Yoktian county than in the gulag. Jakli picked up the paper and read it, then pushed it toward Shan, with wide, excited eyes. He scanned it quickly. It was true. Someone had put a new life together for him. He was to be reincarnated once more. There was a community of Chinese exiles in England who would welcome him. He was to live with a professor of Chinese history in Cambridge until he was settled. Eight days. It would take six days of hard travel to arrive at the appointed place near Nepal.

A low rumbling sound rose from the corridor. Shan recognized it immediately. The prayer wheel.

"Bajys," Lokesh explained. "That first night we came he was still incoherent, and he barely had the strength to walk. But then he saw the wheel and began turning it. He was crying at first, then laughing, and he kept turning it all night long." The old Tibetan's eyes were wide and bright, as though he were describing a miracle.

They listened to the rumble for several minutes without speaking. Maybe all would be right, if Bajys just kept turning the prayer wheel. Some of the old lamas might have said that Shan's work was indeed finished, because he had found someone to turn the wheel that had not spoken for centuries.

Finally Lokesh rose. "I must prepare Rinpoche's blankets for the truck," he said and left through the rear doorway.