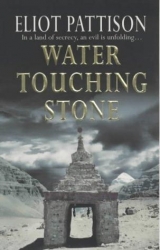

Текст книги "Water Touching Stone"

Автор книги: Eliot Pattison

Жанр:

Полицейские детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 32 (всего у книги 38 страниц)

Shan lay on his back, his head on his hands. He could hear the American's quiet breathing behind him. He reached and ran his fingertips along the stones, feeling a strange affinity for the builders of the karez. Other men had been here before him, worshipful men laboring in the dim light of oil lamps, tapping stones and supports into place, taking the measurements that assured gravity would move the water. Some paused to paint inscriptions in the tunnel, where no one would see them. No one but a small desperate group of castoffs, centuries later.

What would it be like when someone pulled his body out in a thousand years? Someone who would study his clothes and declare, How strange, this dried-up Han with an old Tibetan gau wore twenty-first-century textiles and had a tenth-century medallion in his pocket.

"Is it true," Deacon's voice came through the blackness, "that there are lamas who can speak with mountains?"

Shan smiled in the dark. "I think mountains might have much to say."

"A mountain is full of age," the American said very slowly, in English now. "And water and crystal and roots. I could learn from a mountain." He breathed silently for a few moments. The lack of oxygen was beginning to tell. "I used to walk in the mountains. I sat under huge trees and just absorbed everything. I stopped thinking, I just felt it. For hours."

"A meditation," Shan said.

"I guess. There are people in Tibet who do that for years, I hear. If I did that for years I would– I don't know. I wouldn't be me anymore. I'd be something better. Something more than just human."

"I've known people like that," Shan said softly.

"Then you're lucky. Me, I guess all I do is just hope that if I do real good– you know, acquire merit– that in the next life I can get to be a hermit in Tibet."

They were quiet again. Deacon lit another match and held it closer to the bricks, apparently studying the construction. There was no sound from the others. They could be lying in a cave-in, already dead. Perhaps that would be better than the torture of slow suffocation in the blackness. Shan felt something on his hand. Moisture. He wiped the sand from a bottom stone and laid his finger across it. After a moment the finger was damp. He pushed aside the sand and laid his cheek in the dampness on the rock. There was something of a miracle about it, he thought, something of great power in the dampness, something akin to the feeling he had known when he had touched the pilgrim's mummy, as if the dampness itself were a thousand years old.

Shan pushed his cheek down against the stone. He had been to a well outside an old gompa, where pilgrims came to drink. During the Chinese invasion, a khampa child had gone there, after being forced by the soldiers to shoot both her parents. She had cried for a week over the side of the well, and later the monks had covered the hole so the invaders would not fill it in. They opened it for visits by the faithful. Her tears were still in the water, the monks said solemnly, for once the tears had mixed in the well, no matter how many buckets came out, something of the tears remained.

He felt the moisture on his cheek and wondered how many tears had mingled with it. All those who had cried in the mountains beyond, for all the centuries, had something of their tears in these waters. He realized that though he had felt a great thirst earlier, the thirst was gone. A memory, a snippet of conversation with Malik came back to him. Is that how you know you are dead, Malik had asked, when you have no more thirst?

"If mountains could talk," Deacon asked through the darkness, "what do deserts have to say?"

"The same thing," Shan said, "only with sorrow."

"What do you mean?"

"Deserts are where the mountains go when they die."

There was silence again. His consciousness seemed to fade, as if he were falling asleep. He put his fingertip on his eye, unable to tell whether it was open or shut. He heard something. Music, and a falsetto voice. If bits of water could linger for centuries, he thought, maybe particles of sound could do the same, gathered into the karez by ancient winds. Maybe it was what the wind demons did, gathered up pieces of human lives and deposited them into quiet, shadowy places.

He smelled ginger and heard a voice that was unmistakably his father's. Not specific words at first, but tones, as if his father were humming, to comfort him. Then he heard his father speak, in a tongue he had never known. Khoshakhan, he was saying to Shan. Khoshakhan.

A trickle of sand fell into his mouth and Shan choked, coughing, awake again. "Back at the Stone Lake," he said wearily, "when it was an oasis, it would have been a good place for crickets."

A sound like a muffled laugh came from behind him. "We found a scroll last week," Deacon said. "An essay, on the proper diet to feed singing crickets. Ming dynasty. I'm going to show it to Micah. We'll mix up some of the recipes and see how they work."

"At the full moon."

"Yeah." The American paused before speaking again. "It's going to be hard."

"Hard?"

"When he hears about Khitai. The Maos told us what happened."

"You said they were friends?"

"Khitai was the best friend Micah made here. Lots of mischief together. We were excited about the news, that Micah would have a brother now. Warp was already expanding the house in her mind. Buying bicycles."

"I don't understand-" Shan began, then he realized Deacon was speaking of the future. He rolled over, pressed his back against the moisture, and extended his fingers into the darkness. There was nothing like being blind to make a man see. Marco had not known where Lau had planned to take the Yakde Lama. But Deacon did. "Khitai," he said. "I understand now. You were going to take him to America. You were going to take him after the full moon." It seemed odd now, talking about the future, as if they had become disconnected from it, as if they were speaking of other people's lives.

Deacon didn't answer.

"I know about it. The Panda. The medallions. I just didn't know how far he was going."

"Somebody told me once that no one should die with secrets. So I guess I can tell you mine and you can tell me yours." Deacon paused and breathed rapidly, as if speaking had become a great labor. "Micah and Khitai were hatching out ideas to be together long before the trouble started. Then a month ago Lau came to us all upset and explained about the boy, about who he was. Said things had changed, that she might have to find a new home, that she would have to get Khitai away. Maybe we could say he's our new adopted son from China. Warp acted like it was predestined, the perfect thing for us to be doing. Marco can get us out. Marco knows people outside, he has lots of money, in banks outside. He had papers made, good ones. U.S. passports he bought in Pakistan." Deacon sighed and seemed to sink back into his thoughts.

The silence of the grave. It was weighing on the American too, Shan knew. The silence seemed to shout. It seemed physical, as if pressing down, as if the tunnel were shrinking around them. He raised his fingers slowly, until they made contact with the top of the tunnel.

"I don't understand," Shan said.

"What?" the American asked. It seemed as though sound itself had slowed, as if ages passed between his words and the reply.

"I don't know. You. Why you and your wife came to Xinjiang. Why you would send your son to clansmen you don't really know."

Deacon was quiet so long Shan wondered if he had stopped breathing. "A splinter," he said. "It's all because of a splinter."

"A splinter?"

"We were in the Amazon jungle. It got infected, real bad. Warp was with me, and two Indian guides. We were doing an article on weaving techniques in one of the disappearing tribes. I was delirious off and on, I was going to die, I knew I was going to die. Fever. In and out of consciousness. She sat with me, wiped my brow, talked with me while the Indians looked for medicine in the jungle. I made a vow that if I lived it was going to be different. We were going to make a difference."

Slowly, sometimes pausing to draw in a deep breath of the depleted air, Deacon explained that he had spent much of his youth roaming the world, seeking adventure, spending most of what his father, an automobile dealer, had left him. "Kayaking for a month in Tasmania. Climbed four mountains in Alaska and Nepal. Bungee jumping in New Zealand. The Andes. A month in Peru. A month in Patagonia."

"Doing research?"

"Hell, no. At least, not often. After we got married, sometimes Warp would go on my adventures and pay her way by writing an article. I was just a thrill seeker. She settled us down for a while, said I had to grow up. Got jobs at the university, good jobs. Micah came. Then one day we're at a shopping center, a place where many stores are all together, in a cement maze. Had a big basket of toys, waiting in line. Suddenly I see she's crying, tears rolling down her cheeks. She says here we are, playing along. It's how everyone measures their lives, she said, when you have young children you go to the giant toy stores and buy expensive plastic things. They get older and you buy expensive electrical things at a different store. Then it's expensive clothes. If you're really successful, expensive shoes and expensive cars. It's called Western evolution, she says. You mark your existence, and your place in the herd, by what stores you shop at. I said it's just some toys, Warp. But when it came time to pay and she reached into her purse, her hands were shaking so much she couldn't hold her wallet. She couldn't move. Just cried and cried. Police came, then an ambulance. They put her in a place like a hospital for a week. Some fool heard about it and told Micah his mother had a breakdown in the toy store. He came to me– he was five– with all his toys in a big box and said he would give them up, never have toys again, if they would give his mama back. I went to the hospital and took her out, told them they were the goddamned crazy ones, not my wife. We agreed we would take every research project that came along, to get away from the world.

"Then months later I lay dying in the Amazon. I said to her, I married the wisest person in the world. You were right that day in the toy store, I told her. Nobody's accountable. People sit back and let bad things happen. Forests get leveled. Cultures get destroyed, traditions get cast aside because they're not Internet compatible. Children get raised to think watching television is required for survival and get all their culture from advertising. We pledged to each other if we got out of there we would make it different for us and Micah. We would be accountable, and we would find a place where we could make a difference."

"And here you are," Shan said distantly. "In an ancient tunnel under an ancient town, just waiting-"

"No regrets," the American shot back, as if he did not want Shan to continue. "Our government and the Chinese government doesn't want us here. Screw them. This is where it is, this is where we make the difference." Make a difference. Oddly Shan recalled, Prosecutor Xu had used the same words just the day before to explain why she was in Yoktian. "These people, Beijing thinks they're broken. They're not. They're just waiting. All we do is what you do. Help them find the truths."

"But your son." Shan tried to pretend that he was simply lying on a rock under the open sky, talking in the night.

"Two hundred years ago in America ten-year-old boys were out hunting food for their families. They were learning how to survive, how to build barns and cabins, how to ride, how to heal a sick horse, how to shear a sheep. That's what our boy is learning, essential things. The first things, Warp calls them. Hell, I couldn't even teach him some of them. But the old Kazakhs and Tibetans, they know. We trust them like family. After the first two weeks, Micah said he wanted to switch families, that his shadow clan didn't have any horses and he wanted to be with horses, like the Kazakhs, like his mother's ancestors. But we said stay up there, learn about the sheep for now. Lau said she would make sure he didn't switch among the zheli families. He's safer with them than anywhere."

Deacon's voice drifted off. But Shan knew what he was thinking. Thank god the boy had not come to Stone Lake, to die with his father.

Shan was under one of the support beams. In the darkness he traced the contours of its carving with his fingers. A dragon head. A flower. He broke the silence a few minutes later. "What kind of New Zealand animal is a bungee?" he asked somberly, wondering whether, after a lifetime of questions, he only had a handful left. "And why would you jump over it?"

The sound that came out of the American was a rasping, wheezing noise that Shan knew was intended to be a laugh.

"Okay," Deacon said after he explained. "How about you? A secret."

Shan thought a moment. "I was a bad father."

"Come on. What man isn't? Every man with a child is a good father and a bad father, all in the timing."

"I was a disloyal worker."

"I hope so. You worked for the People's Republic, for chrissake. Not good enough."

"In my heart," Shan said at last. "There is constant pain. Because I am Chinese and China has forsaken me."

His consciousness seemed to flutter, and he wondered if perhaps he had passed out. He said Deacon's name, and the man made a small moaning sound. He inched forward, wide awake now, and touched the first of the rotten beams. He called to the American. "If we could ignite the fallen beam we could use it as a torch, see our way forward."

"And burn up what oxygen is left," Deacon said in a hoarse voice. "And if we move the wrong way, even in the light, it could collapse."

"Maybe," Shan suggested, "that would be better than slow death over the next few hours."

He could hear Deacon venturing forward. As the American approached, Shan found his hand in the dark and placed it on the beam. He produced one of his matches, lit it, and held it under the end of the beam. The wood smoldered but did not ignite.

"Not hot enough," Deacon said in a voice devoid of confidence. "Make a pile of the rotten chips, start them first."

They tried it and failed. Deacon had three matches left, Shan had four, and they laid all the American's matches on the pile and lit one of Shan's. The pile sputtered, flared, dimmed, and burned out. Silently Shan pulled papers from his pockets, his notes, his evidence, and crumpled them into a pile and lit them. They flared into a small but steady orange flame. He fed it more chips while Deacon held the beam over the flame. In two minutes they had a torch and were moving down the fragile tunnel.

A beam sagged as Deacon passed, then broke behind him. They crawled like snakes over a pile of rubble that rose to half the height of the tunnel. Shan moved at a snail's pace, knowing that his next movement could be his last. Their progress was agonizingly slow. The wall shifted once, and buried Deacon's arm. Slowly the American dug himself out, then gestured Shan on. Twice the torch dimmed, as if about to extinguish, but Shan thrust it forward as far as he could reach until it found oxygen and revived.

Suddenly Deacon called out in a loud whisper, "The wall!"

On either side was solid stone, huge cut pieces, with long slabs of stone overhead.

"A building foundation!" Deacon croaked excitedly. "It would have access, a tap to the karez."

They moved faster. Then, twenty feet later, Shan froze. A spirit hovered fifteen feet ahead of him, a shape that glowed and shimmered. Deacon saw it and cursed. Shan crawled closer and his heart leapt. It was light, a small shaft of sunlight. But it came through a tiny crack in the stone, only a quarter-inch wide.

The tunnel curved as they proceeded, then suddenly Shan saw a fire with a face in it, a sight that frightened him so much he dropped the torch.

Then the face spoke, with a woman's voice. "Shan!" it called, and they saw it was Jakli, with a torch held below her face.

In five minutes they were out, gasping great lungfuls of fresh air as Akzu and Kaju pulled them through a two-foot opening in the tunnel ceiling, into painful, brilliant sunlight. They were at a ruin in the side of the dune at the northern end of the bowl.

"The flashlight was almost out," Kaju explained, extending a water bottle. "We couldn't use it to go back. Then it took so long to find wood for a torch."

They drank in great gulps as Jakli and the boys explained to Akzu their ordeal in the darkness and the miraculous appearance of Deacon and Shan.

But Shan wasn't celebrating. He was exploring for papers he hadn't burned, the ones that he hadn't reached in the tunnel. The small folded paper of abbreviations from the dead American was still there. He refolded it and stuffed it into his shirt pocket. The only other paper was the map he had drawn of Karachuk. He turned the map over. It had been in the trash, used by the Tadjik to wrap the baseball he had stolen. It had been nothing, he had thought then, just blottings from a pen, strange lines in different degrees of shading.

Deacon approached him and handed him the bottle. "I was thinking, Shan," he said, squatting by his side. "You should come. Next week. Under the moon, with my son and me. I want you to. I was gone down there. You saved my life."

But Shan only half listened. He was watching Jakli, who now stared at him with anguish in her eyes. She stepped away from Akzu and approached him. "Bao didn't leave because of what Akzu told him," she said. "He left because there was a report on his radio that two old Tibetans had been seen on the highway."

Shan felt his head sag. He stared absently at the paper in his hands, fighting a wave of despair, until suddenly the American grabbed the top of the paper and pulled it toward him.

"Where the hell-" Deacon exclaimed and bent to examine the line of tiny print at the top of the page.

"That Tadjik had it," Shan said, "the one at Karachuk. Do you know what it is?"

"Of course. Genetic mapping sequences. A copy of our lab results. What's the point?"

Shan thought a moment and looked up with alarm in his eyes. "That Tadjik was much smarter than I thought. He wasn't trying to steal your white ball. The ball was cover, a distraction in case he was caught. He was trying to steal this, to take it to someone."

"Jesus." Deacon sat down heavily on the sand and pointed to the print at the top of the paper. "A lab registration number, for our lab in the United States. Big secret, until we publish. This lab code gets out, everything gets shut down. The knobs will know who we are. Washington and Beijing will be all over us." Deacon gulped down the remainder of the water and tightened the straps on his backpack.

Shan had one match left. He used it to burn the paper, then watched the American with a pang of guilt as he jogged off to his horse. He hadn't told the American the worst of the news, that his son, the last of the hidden zheli, was now undoubtedly the next target of the killers.

Perhaps, he thought absently, there would have been advantages to being buried in the desert. Now, finally, he had to decide. Others were going to be taken, to be killed or imprisoned. He couldn't stop it all. He could try to save Gendun and Lokesh or he could try to stop the zheli killing. But he couldn't do both.

Chapter Nineteen

It seemed like days had passed inside the karez, but it was only early afternoon by the time they reached the highway. Akzu embraced Jakli repeatedly as they departed, making her promise with each hug to be at the nadam early, until she began to smile, then softly laugh. Her aunts had secretly made a wedding dress, he told her, so she had to come early but act surprised. Before the Kazakh left, Shan asked Jakli if she knew the way to the camp where Marco had sent the Tadjik thief. She consulted her uncle briefly. Wild Bear Mountain, Marco had said, near the ford of Fragile Water Creek. They did not know the camp but they knew where to find a guide who would know.

"I thought a dust demon had taken you," Akzu said in a distant voice before departing. "They do that sometimes." He had listened in seeming disbelief when they had explained their passage through the tunnels, and now looked at the sand on their clothes, their skin, their hair and nodded solemnly, as though confirming his suspicion. "Sometimes, they bring you back just as sudden," the old Kazakh observed. "You wouldn't remember," he added solemnly.

Kaju studied the landscape with an unsettled expression, as if looking for other escape routes. He would have to come back in five days, for the next class. He had promised the American, for that was the appointed time for Deacon's son to return to his parents.

Jakli seemed to sense Shan's thoughts as they drove west, away from the desert. "He's out there, with Sophie," she reassured him. "Marco will find your friends. There is no one better for the task. He will take them to safety. They're probably on the way to his cabin now, singing Russian love songs with him."

Half an hour later Jakli eased to a stop at a crossroads jammed with people. Near the intersection was a shack with a wire fence behind it, holding a flock of goats. They stopped and walked to the gathering. More than two dozen people crowded the intersection, some carrying stones, others sitting in reverence before a growing cairn of rocks. Some were listening to a man who sat atop a broad log that served as a corner fencepost, speaking with great animation. A man on a horse rode up and asked where the holy place was. The man on the post pointed to the rocks and the other man dismounted, untied the wing of a large bird from behind his saddle, and walked to the rocks to fasten it to the cairn.

It was a shrine. For the miracle that had happened. The people were kneeling now. The rocks were arranged in a narrow pyramid nearly eight feet high. A rope was tied to a stick at the top, staked to the ground fifteen feet away, and a fragment of cloth was attached to it with Tibetan words. A prayer flag. Shan watched in confusion. Buddhists, down from the mountains, were putting on prayer flags. The Kazakhs and Uighurs were putting on feathers, pieces of fur, and the wing of a bird.

Shan walked through the excited throng, asking questions. The two Tibetan holy men had come through the day before, in the late afternoon, resting their donkeys at the crossroads. Others came with them, nine or ten others, old women, small children, a herder with a bad leg, some on horses or donkeys, some walking. Like a pilgrimage in the old days, a woman with grey hair said.

One of the holy men, the one in the Buddhist robe, had spoken with each of the followers, even the children. The other man, whose eyes twinkled when he spoke, had also listened to them, not to their words, but to their bodies, finding the words spoken by arms and legs and stomachs that no one else could hear. He had given herbs to some and advice for exercise of limbs to others. A dropka woman galloped up with a baby, asking the thin one with the red robe to give it a name. Once, Shan recalled, Tibetans had always asked lamas for the names of their children. Then the robed one had assigned journeys of atonement. This woman was to go see her brother whom she had not spoken with in ten years because he had given her a lame horse, that woman was to go a mountain lake and drink its waters, then build a shelter that wild animals might use in the winter. The lame man was sent to meditate where young colts slept. "A synshy," the man who had just ridden in said knowingly. "The man in the robe was a horsespeaker." Several in the crowd nodded knowingly.

But that had not been the miracle, the man on the post said. The miracle had come later, when the knobs arrived. Shan's head snapped up. A chill crept into his stomach. Only three young knobs, in a small truck. They seemed to have been searching for the holy men, and two stood guard with guns while the third, a woman knob, talked excitedly on the radio.

The people had gotten angry and told the knobs that they should be looking for the killers of children, not old men. The knobs had gotten out hand chains then, and somebody had thrown a rock at one of the knobs. They had pulled out their weapons and one shot a gun in the air, several shots, on automatic. The man with the robe– Gendun– covered his ears then, and when the gun stopped he lowered his hands and asked if the man was finished. You make it very hard to talk, Gendun had said, most earnestly, and the Chinese man who fired the gun had looked confused, then apologized.

Then Gendun had stood in front of the knob who had been hit by the stone and told the people not to hurt the young soldiers. He had spoken to Lokesh and Lokesh took the chains and fastened a pair on Gendun, then Gendun had fastened a pair on Lokesh. The lama had then asked the knobs to sit for a moment with them, to share some food. Two of the knobs had done so, and Gendun said a prayer while a herder handed out pieces of nan bread. Gendun had asked the knobs their names and he said the knob woman had a strong face and would make a good wife for a herder. People had laughed.

But even that was not the miracle, the man on the post said dramatically. The miracle came next, when a limousine arrived and the Jade Bitch appeared. People had shuddered, some had run away. The prosecutor had stood silently, looking at the Tibetans and the knobs. Then Gendun had walked in his chains to stand in front of her, smiling. She had stared, a long time, as if in a trance. Then she had spoken on her radio and told the knobs to leave, to release the two men and leave. The woman knob had argued, and the protector had shouted at her. Before the knobs left the prosecutor made the knobs give her the chains used on the two men. People had thought she was going to take them away herself, to her prison camp at the foot of the mountains. But the Jade Bitch had walked to the two men, dropped the chains at their feet, and driven away. That was the miracle.

The chains, where she had dropped them, were under the cairn.

Shan looked in silence at the cairn, then at Jakli.

"She just doesn't want to share them with the knobs," Jakli said. "She wants them all to herself, without the knobs knowing."

"I don't know," Shan said, staring again at the cairn. "Sometimes miracles do happen." He walked away to find a rock for the cairn, then asked the man on the post what had happened afterward. Night had come, he said, and they had built a fire and talked under the stars. But when the sun rose the holy men were gone.

Shan gazed toward the desert. It would be night again in a few hours, and cold.

"They don't even have a compass," Jakli said with a tormented voice.

"No. They do," Shan assured her. "Just not the kind you or I could read."

"Marco and Sophie are at the Well by now," Jakli said, but her voice showed no certainty. "Sophie could find them. Sophie could smell them. Marco probably went to Karachuk. Maybe Osman is helping now. And Nikki," she added softly.

But thirty minutes later as they drove into the next village, Marco and Sophie were in the middle of the street, surrounded by Public Security troops.

Jakli eased the truck behind a building and they looked around the corner. The village was under the control of the knobs. They had erected a security checkpoint in the square and were checking the papers of everyone in the village and all those traveling down the highway. A queue of over a hundred people stood in front of a table where three officers examined papers and stamped the hands of those who had been cleared. Two knob soldiers with automatic rifles stood at the door of a blunt-nosed grey bus with heavy wire on the windows. Half a dozen forlorn faces looked out of the wire. Beside the bus was a grey troop truck, and two hundred feet beyond that a red utility truck sat with two men in the front seat. The Brigade was watching. Watching not the crowd, but the knobs.

Jakli desperately searched the faces of those in the line. She looked back at Shan anxiously, then searched again and sighed with audible relief as she noticed a teenage girl walking by. Jakli pulled the girl around the corner and spoke in low, urgent tones. She raised the girl's hand and studied the image placed there by the knobs. A circle of five stars in red ink. She released the girl's hand and spoke a moment more, then the girl walked briskly away and Jakli pulled Shan into the line.

Jakli asked the man ahead of them what the Eluosi with the beautiful camel had done. It was Marco Myagov, the man said in an admiring tone, with his silver racer. Marco, he explained, had done nothing except to refuse to leave his camel while he waited in line, so an officer had ordered him to wait until everyone else was done. As the man spoke the camel gave a small snort. She was looking directly at Jakli and Shan, cocking her head as if about to speak to them. Marco followed her gaze, gave a small frown as he recognized them, and looked quickly away.

Shan watched the officers at the table as they worked. They looked at faces first, then papers. Woman and children were passed through with a quick glance at papers and a nod. Shan saw a Han man go through with the same treatment. An old man got through without a second look, and another. The knobs were looking for someone in particular. Not a Han. A man, but not an old man. Shan's only hope was that they found him soon, or Shan would be on the bus, as one more illegal caught in the sweep.

There was a sudden commotion at the front of the line. One of the officers was standing, telling a man to take his hat off. He pulled the man to the side and questioned him while the other two officers carefully examined the man's papers.

"Who is it?" Shan asked quietly.

Jakli spoke to the man in front again. "He doesn't know. Some Tadjik. It's good. We need the time."

For what, Shan thought. Another miracle?