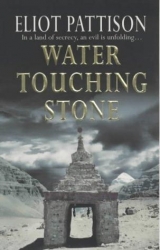

Текст книги "Water Touching Stone"

Автор книги: Eliot Pattison

Жанр:

Полицейские детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 14 (всего у книги 38 страниц)

Hoof lowered his arms and nodded slowly, then more vigorously, as though grateful for Marco's mercy.

Shan stared in confusion. Marco had just sentenced the man as surely as if he had been in a courtroom before armed guards.

At the corridor Osman spoke with Hoof's companion, who grimly nodded and escorted his friend out of the building. Shan stared at the empty doorway. It had been foolish, what the Tadjik had done, almost unbelievably foolish, as though perhaps he had had another motive they had not seen. He picked up the ball and tossed it from hand to hand, until he noticed that it had words imprinted in English. "Made in America," he said to Jakli, translating to Mandarin. He used the traditional Chinese words for America: Mei Guo, Beautiful Country.

"Beautiful ball for a beautiful country," a deep voice said from behind him, in English. Shan turned with a start to see a tall man in his mid-forties, with sandy-colored hair turning to grey. A pair of bright blue eyes stared at Shan from behind gold wire-rimmed glasses. The man raised an oversized leather glove in his left hand, punched his right fist into it, and opened the glove toward Shan. "That would be mine," he said, his eyes full of challenge.

Shan weighed the ball once more, remembering at last what it was, then tossed it into the glove. "Baseball," he said in English, in an awkward rhythm. The last time he had pronounced the word out loud had been with his father, over thirty years before. He returned the stranger's steady stare. "You're American," he added, as an observation, not a question.

"Dammit, Deacon," Marco muttered. "You don't know him."

"He's with Jakli," the man said. "That's good enough."

Meaning what? Shan wondered. That the American was usually hidden from strangers. But also that Jakli had a much closer connection to the two strange men than he had thought. Shan studied the man named Deacon. There had been another American hidden away, inside a burlap death shroud.

"Jacob Deacon," the American announced, extending his hand to Shan. "Just Deacon will do. You're a friend of Nikki's?"

Shan returned the handshake uncertainly, looking at Jakli.

"A friend of some Tibetan priests," Jakli said.

"Okay," Deacon said with a small smile. "I believe in Tibetan priests too." He looked at Marco. "How about you?"

The Eluosi frowned. "I've known priests and mullahs. And I've known commissars. Commissars are easier to deal with."

Deacon laughed and pounded Marco on the shoulder, then pulled a bottle of water from a carton behind the bar. He poured a glass for Shan, then one for himself. "The real thing. And it's free." Shan studied the man. Had he been listening from the rear corridor the entire time?

"When is Nikki coming?" The question burst from Jakli with a sudden energy that caused Shan to look back at her.

"Caravans are unpredictable." Marco shrugged. "Maybe he decided to hole up in Ladakh for a few days because of patrols." He placed one of his paw-like hands on top of Jakli's head for a moment, the way a father might touch a daughter. "He'll bring you something bright and shiny. Or maybe something soft and flimsy."

Jakli's face flushed and she good-naturedly batted Marco's hand away, then quickly grew serious again. "Shan needs to know about Auntie Lau. Two of the children have died now too." Osman cursed. Marco raised his head with a growling sound, suddenly very sober, as Jakli explained about Suwan and Alta. "Shan thinks it started with Lau. He needs to know who might want to kill her. What happened before she died."

"A good woman," Marco said solemnly. "A bad death."

"Why would someone do this to an innocent woman?" Shan ventured.

"Innocent?" Marco asked. "That's more than I know."

"You don't consider her innocent?"

"Of course not. Are you? I sure as hell am not. Osman's not. My camel's not. They've proven Jakli's not innocent, three times over." The words brought a bitter smile to Jakli's face. Marco looked over to Osman. "Ever meet an innocent person, old friend? I haven't. Hell, Osman's got a niece six months old, still at her mother's breast. She's not innocent. She's Kazakh."

"You're saying Lau was killed because she was Kazakh?" Shan asked.

"No. But maybe in the end that's what it was. What being Kazkah made her do. The bastards."

"What bastards?"

Marco poured the remains of the vodka into a glass. "Just bastards in general," he muttered.

Shan turned toward the rear corridor. The American was gone. He felt Marco's gaze.

"You'd be wise to be gone yourself," the Eluosi observed in a dangerous tone, wiping his mouth on his sleeve. "It's a bad place to be asking questions."

"If you would talk with him," Jakli suggested, "maybe he wouldn't have to ask so many."

Marco sighed. He stepped behind the bar and retrieved three of the flat nan breads. He tossed one to each of them, then mounted a stool and chewed meditatively on the third as Osman collected glasses from the tables. "It was just before Nikki took the last caravan out," Marco said. "We had to pick up some men. Lau rode in that evening, all excited about something."

"Alone?" Shan asked.

"Alone. Her horse was so exhausted we were scared it would die. Osman stayed with it, rubbing it, walking it, making sure it was copied down before drinking."

"Who did she speak with?"

"No one. Everyone." Marco stared at his crust as he spoke, then looked up with a new sadness in his eyes. "They say she was a healer, but many didn't understand the most important thing she did, the most important healing." He paused to bite off a piece and chew. "There's a little brown mouse in the desert," he said in a contemplative tone. "It collects things, like a pack rat. But where the mouse lives is so harsh that it usually just collects thorns and sharp pieces of crystal and small dried dead things. Lau was like that, with people's troubles. People would tell her their nightmares, their painful memories, their fears, and they would feel better, like she had taken them away, collected them inside herself, so they could heal."

"You're saying people confessed things to her?"

Jakli nodded. "It's true. I keep wondering. What if someone told her something, a secret she wasn't supposed to know? What if they changed their mind later and decided she had to be silenced? People get drunk and talk. She had a way of getting people to talk."

"No," Marco disagreed. "You didn't see her that night. The way her legs were beaten. If you want to stop her from spreading your secret, you just shoot her. If you want to pry out someone else's secret, you beat her first."

Shan took a bite of his bread and looked up. "You mean, you saw her."

Marco stared at his piece of bread. "I mean I found her. Nikki and I. Nikki first, at the quiet place she liked to go to. Only she and Jakli were the ones who usually go." He glanced at Jakli. "Nikki missed you. I think he went there because it reminded him of you. But when he went inside he found her tied to the old statue. He came and got me, with tears in his eyes." The big Eluosi looked down into his hands. "His mother taught him that, that sometimes it is all right to cry." Marco raised his eyes to Jakli, who seemed to be fighting back her own tears.

"I used to see it a lot, when the Red Guard were roaming the land," Marco said with a bitter tone. "They would break bones in the feet with a hammer. If you do it just so, it makes the skin agonize to the touch. Then they hit the feet and shins with a stick. Doesn't take much force to create a lot of pain. Sometimes they just used chopsticks, snap the skin with chopsticks. Do one foot, start with the second if they still don't talk. Afterward, you would see them on the street. The knobs would laugh and call them drunken foot, because they couldn't walk in a straight line anymore. The ones that held out, they did both feet. No one did much walking after that. Her killer, I don't think he intended that she leave the room, no matter what she told him."

Jakli tore away with a sob and ran out the back passageway, followed a moment later by Osman.

"Maybe she didn't talk," Marco suggested. "She was a tough one." He poured them both some tea.

"She talked," Shan said, and told Marco about the bruise on her arm, the place where a syringe had been inserted.

Marco sighed heavily. "What's the point of beating her, then?" he asked into his glass.

Shan looked up into Marco's eyes and knew he didn't have to explain. The injection meant that the killer was someone experienced in interrogation technique. Those who were hardened to it sometimes developed appetites for watching people in pain.

Marco was silent a long time. "We would have seen a knob or a soldier," he said in a low, angry tone.

"Not if he was well trained. Or if he was disguised," Shan suggested, and related what Prosecutor Xu had said to him at Glory Camp, how she had mistaken him for a knob agent.

"God's breath," Marco said, and shifted in his seat to face the empty tables, as if trying to fix in his mind each of the faces of the men who had occupied them. "It's a bad time."

Shan watched the brooding Eluosi. A bad time just because of the treachery, he wondered, or bad timing for the treachery, because of something else?

"Why here?" Shan asked. "You were here. A few others. This settlement here, it's not a big place, not easy to hide in. I think the killer took a big risk, killing Lau here. But he had to, because suddenly it was urgent. He couldn't wait."

"Nothing's changed."

"Not yet," Shan said and saw Marco clench his jaw. "What if the secret she died for was your secret?"

Marco drained his tea in one long gulp and fixed Shan with a stare. "You should go home, Comrade Inspector. I will get the bastards."

"You sound as if you know who did it."

"Not yet. But it's what I do. I get bastards." He spoke in a stark, haunting tone, as if it were a threat against the entire world, including Shan. "My hobby," he said with a thin smile. "I remember. I watch. I make sure others don't forget."

Shan considered Marco. A forgotten man of a forgotten people, without legal travel papers, without hope of ever getting legal papers. Not unlike Shan. Maybe that was all that Shan was about too, about getting the bastards, whomever they were. He recalled what Marco had done to Hoof. He had gotten the bastard.

Marco suddenly appeared very tired. He stretched and lifted his heavy frame from the stool, then moved to the center of the room and collapsed into the overstuffed chair. He shut his eyes and quickly drifted into the deep slow breathing of slumber.

Shan sat silently, trying to make sense of Lau's killing, trying to keep at bay the question that lingered constantly at the edge of his consciousness, the question of Gendun and his safety. From the basket he retrieved the paper that had been wrapped around the ball, flattened it, and sketched on its clean back a rough map of Karachuk, to have a context for the location of Lau's killing, to fix the spot when Jakli finally showed it to him. Lau had not died in this room, or in the nearby huts. He remembered Bajys' words. He had gone to the place of sands to find her, to the lhakang there, the sanctuary place, which, Shan knew, must be the quiet place Marco referred to, the place where Lau's body had been found. But he had been too late. He hadn't found her in Karachuk. He had only found pieces of bodies. She had died tied to a statue in the quiet place, Marco had said. Shan sat on the floor by the bar, in the cross-legged lotus style, contemplating his map, then finally rose and moved out the rear corridor.

The passage led down a curving hall to a small plank door that opened to the east, at the back of the makeshift community, onto a sandy swath, across which stood the rock outcropping that defined the eastern boundary of the ancient city. The sun was low in the sky. A cool breeze was blowing. There was no sign of life, except in the corral, where the horses had been joined by half a dozen camels, including one huge silver creature that seemed to study Shan as he moved.

Shan climbed halfway up the rock, stopping when he was just above the domed building. He sat and leaned against the warm rock, drained mentally and physically. Someone had tortured a woman here, a healer and a teacher. She had been killed for a secret, but in order to find her, her killer had penetrated another secret, the secret of Karachuk. Because she had not been just a healer and a teacher. Lau had lived in many worlds, it seemed, just as Shan had traveled through many worlds to arrive here, at this ghost city in the desert where the gentle Lau had met her violent end.

He pulled out the paper he had taken from the dead American and studied the strange combination of letters. FBP the first line said. Could it be a code for numbers, with F meaning six, for the sixth letter of the English alphabet? He quickly calculated that FBP would mean six, two, and sixteen. Meaning what? An address? A phone extension? Or were the letters geographic abbreviations? FBP could mean Frankfurt, Beijing, and Paris, or a thousand similar combinations. He sighed and took comfort from the knowledge that the paper wasn't for him, not part of the mystery he was meant to solve.

His eyes fluttered with drowsiness. For a moment he saw Karachuk the way it had been, smelled the spices brought by the caravans, heard the creaking of well ropes, the laughter of youths dead all these centuries. It was still an oasis after so many years, it still attracted refugees from a harsh world outside. Perhaps the very fact that its current inhabitants were outcasts from politics and technology meant that they were much like the original citizens of the town. A dog barked from somewhere, whether from his dreams of the past or from the present he could not tell. The wind blew a sheet of sand around the shoulders of one of the stone sentinels on the distant wall, making it appear as though it were wearing a cape that flapped in the wind.

A small sad smile rose on Shan's face as he looked out over the ruins and contemplated not the mystery of Lau's death, but the mystery of life. He closed his eyes and let the timelessness of the place seep through him. A fragrance of spice wafted through his imagined caravan city, like the ginger he always smelled in those rare, perfect moments when he was able to conjure up a vision of his father. But when he opened his eyes to a dusk sky streaked with vermillion, the smell was so pungent that he stood to look for its source. It wasn't spice, he realized after a moment, but incense, and he followed the trail of the scent toward the top of the rocks.

The outcropping was wider than he had thought, easily a hundred feet across at the top, and in a shadow near the center he discovered steps that descended into a cleft in the rock. He followed the carved steps, worn smooth and hollow by centuries of use, and as he descended he heard a woman crying.

Chapter Seven

The gap between the rocks quickly closed up to form a passageway– not a cave, but a structure created long ago by building a roof over the cleft and squaring the walls with plaster. The first thirty feet were deep in shadow. Wary of falling into a concealed crevasse, Shan was about to retreat when the passage curved and he saw the small pool of light cast by a flickering oil lamp. The flame illuminated a dim image on the wall, the head of a bull with angry eyes, wearing a necklace of skulls. A Buddhist image, the shape of Yamantaka, king of the dead. Shan followed the path lit by another lamp ten feet away, then another, studying with reverent awe the paintings of wild animals and landscapes that came into view on the walls. After the fourth lamp, past a patch of naked rock where the plaster had crumbled away, the paintings changed. There was a gentle-looking deer, an image that had grown familiar to Shan in his visits to gompas, the symbol of Buddha's home in India, followed by scenes from the life of Buddha.

The winding tunnel opened into a broad chamber, which he realized had been a bowl in the outcropping that was covered by a roof. A dozen lamps set in wall niches illuminated what had once been a magnificent painting on the walls, a long continuous scene of a journey through an ancient land. To his left were sheep under willow trees, which grew along a road that linked the scene together. The road passed through low wooded mountains, and horses appeared, ridden by archers. The painting faded into the shadows at the back of the chamber, then emerged on Shan's right with scenes of camel caravans moving on sand toward snow-capped mountains.

Beyond a heavy table near the center of the room were several crude benches and sitting cushions arranged on an old carpet. Jakli sat on one of the cushions, staring at a lamp in her hands. She did not seem to notice as he stepped to the table. On it lay six long rectangular sandalwood boxes, plainly but expertly crafted with delicately fitted joints. Pechas, they were called, the Tibetan books that consisted of unbound pages of silk or parchment stacked inside a wooden case. One was open, and several of its pages were arranged in front of it as if it were being read. Behind the books was a bronze statue of Buddha, a foot high, and beside the large figure were several smaller figures of Buddha in gold, none more than three inches high. Below the table was a wooden box covered with dust-caked cloth. Shan pulled up a corner of the cloth. Inside was a jumble of spindles and cylinders, pieces of the prayer wheels used by Tibetan Buddhists.

He sat beside Jakli. "This was the place, wasn't it?"

She was weeping. No longer with the wracking sobs he had heard outside, not even with great emotion, but as she gazed silently into the lamp, he saw two tears roll down her cheeks. She looked up without embarrassment and nodded toward a pallet near the wall, in the darkest shadows of the chamber. He lifted a lamp and stepped toward the pallet. It was drawn up against a large object, covered with a cloth. He pulled on a corner of the cloth and it slowly slid away, revealing a three-foot-high Buddha carved of stone. The plaster just above the Buddha's left shoulder showed fracture lines extending from a single small hole. Down the left side of the statue a rust-colored stain ran to the floor.

"She started bringing me here years ago, whenever we happened to be at Karachuk together."

"She read the Buddhist books with you?"

"Sometimes. But mostly we sat and talked. It was just a quiet place." She looked about the room with a fond but melancholy expression. "For some people, once they knew about this place, this is where they would always go." Shan understood. He felt the reverence of the chamber. It was a place where he would go. Jakli looked back at the flame. "Sometimes she taught me things about healing. Sometimes, after she had gone to her council meetings, she told me about the silly things people do in towns. Ever since she learned my mother was Tibetan, she helped me keep her memory alive."

"Did you want to become a Buddhist?"

Jakli's eyes had drifted back to the stain on the statue. "Lau would never put a name on it. It was so I could worship my inner god, is what she would say." She held the lamp up, as though to better see Shan's eyes. "It is not a bad thing, to be a Buddhist."

"No, it is not," Shan said with a sad smile and followed her eyes toward his hand. It was wrapped around the gau that hung from his neck.

"Are you one, then?" she asked in a puzzled tone.

Shan thought a moment. "When I was young my father took me to the old Taoist temples. Then they were destroyed. When I was older," he said with a sigh, remembering the secret altars made of sticks in his prison barracks, the rosaries of seeds and fingernails and the prayer wheels made of tin cans, "I was taught by Buddhist lamas. But I keep the Taoist verses alive inside me, for their wisdom, and for my father." He looked at the mural on the wall. And I keep the Buddhist verses in my heart, he almost said, because they brought me back to life after I had died. "I guess I am like you," he said. "A little bit of a lot of things." He looked at the small Buddha. Once, in a prison barracks, he had seen an altar consisting only of a series of curved lines scratched on the wall, representing the outline of a seated Buddha.

"I was never sure. I worried about betraying one of them, my mother or my father," Jakli said in a distant voice. "But coming here– it was Marco who showed me Karachuk, when Nikki and I were children. We would sit on the rock and watch for ghosts. We weren't scared. For centuries Karachuk was inhabited only by ghosts. In the old Karachuk it was different. Look-" She rose and carried her lamp to the fresco on the far side of the table, near the desert caravan scene. It showed a domed building that appeared to be a mosque, with men in the red robes of Buddhist clergy standing in front of it, apparently conversing with mullahs. "Here, the Buddhists and the Muslims learned to live together, to share their wisdom."

He turned back to Jakli and saw her staring at the pallet where Lau had died. "I told her so many things," Jakli said, another tear escaping down her cheek. "What if Lau died because of my secrets?"

"Are your secrets so dangerous?" Shan asked in surprise.

"Maybe."

Shan remembered Marco's words at the bar. They've proven that Jakli's not innocent, three times over.

"Because of the things you went to rice camp for?" he asked quietly, looking at the fractured plaster above the statue. There had been no exit wound from the bullet that killed Lau. Her killer had fired another bullet over her head, into the plaster. To secure her, perhaps to make her sit still while he tied her to the Buddha.

Jakli shrugged. "You know how it is. Chinese pest control. All it takes is a few strong words to be sent behind the lao jiao wire."

"Three times," he said. Three bowls, he thought, remembering Wangtu's words.

"First time, I told a Chinese teacher that she was wrong to say Kazakhs and Uighurs were descended from Chinese. She took me to the headmaster. He hit me with a bamboo stick and I apologized. But when I left, there was a rally outside by the Muslim students. The headmaster said it was my fault, that I had organized a political protest. Eleven months in Glory Camp, memorizing the Chairman's verses. They never let me back into school after that."

"But that was only the first."

Jakli's eyes settled on the oil flame again. "At a collective meeting the Chinese birth inspectors announced a new campaign of enforcement. I stood up and asked them what right they had. We produce plenty of food to feed our families. There's plenty of land. I said they limit the number of babies and keep all the good doctors for the Han. Many more of our children die. It's just slow genocide, I said."

"You said that?" Shan asked in disbelief. "Genocide?"

"That was twelve more months, at a camp in the desert. Everything was full of sand there. It was the truth, what I said."

"I know," Shan said somberly. "But I never heard anyone say it in public."

"Then there was a campaign against smugglers. A tent at our clan's camp was found with boxes of Western medicines and portable tape players. You know, with the little headphones. They had no evidence, didn't know whose tent it was. I told them it was my tent."

"But you weren't smuggling."

"No. But the tent was my uncle's, and the goods were from Nikki. I couldn't let either of them get arrested. My uncle, he has to watch over the clan. And Nikki, they would be tough on him. He would be like a caged tiger if they put him behind wire. For me, all they could charge was concealing evidence. So I got ten more months in reeducation."

"But after three terms, it's hard labor," Shan said soberly. "The gulag." He remembered Akzu's warning when she had first appeared at the trailhead. It's too dangerous for you, he had said to his niece.

Jakli nodded slowly and pushed back a loose strand of hair. "But that won't happen now. Nikki will protect me."

"Nikki. He is Marco's son."

Jakli nodded again and turned her face to Shan's, suddenly smiling through her damp eyes. The strand of hair fell back, and she curled it around her finger with the shy expression of a young girl. "We're going to be married– at the nadam, the horse festival."

Shan looked away self-consciously. He did not know what to say. Marriage, and all it implied, was so distant to him it seemed like some vague concept he had read about in an old book. He looked back silently for a long moment. "But he is away."

"On the other side of the border. One last trip."

Shan nodded. The son of Marco the smuggler was a smuggler himself. "And Lau knew about your marriage."

Jakli nodded, still fingering her hair. "She was filled with joy when I told her. Nikki was always one of her favorites," she added, and her eyes drifted back to the flame.

Jakli was going to marry a young Eluosi, the tiger for whom she had gone to jail. He studied her. The longer she sat looking at the flame, the more frightened she appeared to be.

Shan looked about the chamber again. Lau had been there alone in the flickering light when Nikki had found her body. "Who was here that night, at Karachuk?" he asked, staring at the stained Buddha. He walked slowly along the wall, feeling one moment warmed by the simple beauty of the ancient painting, the next chilled by the thought of the violent death Lau had met there. She moved from one person she trusted to another, Wangtu had said, as though from one oasis to another.

Jakli sighed. "Marco was here, Nikki, and Osman. Others, drinking at the inn. When we took her body to the cave we asked all the obvious questions. For hours we talked about it. No strangers were here. No one even saw a strange horse or camel. A vehicle would have been heard. Osman said it was the ghosts. Everyone laughed, but he wasn't joking."

"A horse could have come," Shan suggested. "It could have been left on the far side of the wall and not have been noticed. Or the killer could have left the horse on the far side of the rock, and climbed over without going inside the old city."

She nodded slowly. "Lau came on her horse. You heard Marco. Her horse was all lathered, she had been riding hard across the desert."

"Because she was rushing to see someone?" He stopped by the table and looked into the box of religious artifacts again. Something glinted in the light. He reached down the side of the box and pulled out a long cylindrical object, capped by a needle. A disposable syringe.

"No one," Jakli said in a faint voice. She was looking at him with a stark, frightened expression. She had seen the syringe. "No one knew she was here."

"The killer knew." Lau was running from someone, Shan thought. And came to Karachuk for sanctuary. He looked back at the statue. In the dim light it looked like the Buddha had been shot and had bled its heart onto the floor.

He stared at the syringe in his hands, then abruptly let go of it, as if it could strike him of its own will. It dropped into the shadows and he stood staring at his empty hand. He paced around the chamber, studying the old painting again, somehow sensing something of Lau. An old monk had told him that sometimes when people died in great pain little pieces of their soul broke away and wandered aimlessly about. "Do you know now why she wrote that letter to the prosecutor?" he asked.

"She didn't mean it," Jakli said.

"No. She did mean it. I think I understand. It was her gift, like trying to protect Wangtu by not giving him any more teas. She was worried about you. Three bowls of lao jiao. Ready to be married. She wanted to be sure you were protected, safely held in probation, so you couldn't get arrested again. It would have caused her pain, but she did it for you. She would have sacrificed much, even your feelings toward her, if it meant you would be safe." Despite what Lau had done, Jakli was defying her probation, as if she didn't care, as if she were out of the prosecutor's reach, or would be soon. He looked at Jakli. She was biting her lower lip, tears on her cheeks again, staring at the lamp. He sighed and slipped away.

All traces of the sun were gone as Shan stepped out of the cave, but the sky was brilliant with trembling stars and a rising two-thirds moon. A chill wind blew, the kind some monks called a soul-minding wind from the way it made the spirit wary and instantly alert. From across the desert came the howl of a night animal and, much closer, the chirp of a cricket.

He found his former perch overlooking Karachuk and turned up his collar against the cold. There was no activity, no sign of life, except a few glimmers through the thin cloth that hung in half a dozen windows. His fingers absently ran through the white sand by his leg. He longed to return to the dreamlike state he had felt when he first sat on the rocks, but the vision of Lau dying in the Buddha's arms had burned too deeply. His fingers made random shapes in the cool moonlit sand. Then he stopped, wiped the sand smooth, and made a two-part ideogram. The top was a small cross mark whose ends swept into right-facing curves, with a long tail to the left. It symbolized a high barren plateau and implied emptiness. The bottom half had two Y-shaped figures standing on a curved line, showing two humans standing back to back on a mound. The ideogram meant openness and was the sign his father always used for Chapter Eleven of the Tao te Ching. Using what is not, it was called:

Thirty spokes converge on a hub

What is not there makes the wheel useful

Clay is shaped to form a pot

What is not there makes the pot useful

Doors and windows are cut to shape a room

What is not there makes the room useful

He mouthed the words silently, then heard the last lines in his mind so crisply it was as if one of the Taoist priests of his childhood were reading beside him:

Take advantage of what is there

By making use of what is not.

What was not there, he knew, was the motive, for the motive was the connection that had driven Lau to Karachuk, where smugglers hid, where the American waited– the connection that had taken the killer from Lau to the boy Suwan at the Red Stone clan, then to the boy Alta in the high Kunlun. And on to where? Back to Karachuk? If the motive was simply to find secret Buddhists, the killer might be seeking the waterkeeper. If the motive was to find and kill particular children, then the zheli was the trail, the chain that guided the killer, a chain the killer destroyed as he followed it. Unfinished business, Akzu had said. The clans of one or more of the zheli might have been targeted years earlier, and the killer might have reappeared, as though awakening from a long hibernation, to stalk the last survivors. Kazakhs and Uighur clans had fought soldiers years earlier and been destroyed or dispersed in punishment. But they had inflicted significant losses on the army, and perhaps somewhere had kindled a lust for revenge that had smoldered for decades. Lau may have been alive during those terrible years, but not the zheli. What kind of bloodlust burned so deep it drove the killer even to the offspring of his enemy?