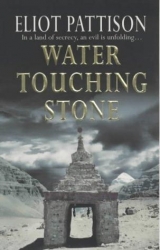

Текст книги "Water Touching Stone"

Автор книги: Eliot Pattison

Жанр:

Полицейские детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 37 (всего у книги 38 страниц)

Shan didn't understand at first. The words weren't spontaneous. They had been chewed over by Marco and he meant them.

"Come with me, Johnny," Marco said in English. "I'm leaving this forsaken land. You should too. I've got buckets of money in banks outside. We'll go to Alaska. Catch big fish. Build a cabin by the ocean."

Shan's mouth opened and closed again. He looked at Gendun and Lokesh, and explained to them in Tibetan, but they offered only small serene smiles and nodded.

"It isn't over," Shan said. "There's no time-"

As if Shan's words were a cue, Kaju shouted. Two riders on horseback had appeared from the desert, leading a heavily loaded packhorse and an empty saddle horse along the back of the dune they sat on. "The Americans," Kaju announced brightly, as if somehow the arrival of Deacon and his wife assured their success.

But Shan just looked at the sand by his feet. He realized that unconsciously he had hoped they would not come.

Deacon's wife seemed to overflow with energy and excitement. She had brought a large jar of peanut butter, which Kaju explained to Gendun and Lokesh, offering samples to them as they examined it with schoolboy curiosity. She spoke to Marco, to make sure the bags on the horse were not too big, then flattened an area of sand and laid a towel on it, then arranged things on it. One of the leather gloves used for baseball. A small green toy truck. A pack of chewing gum. And a red can, battered and dented from heavy travels, an unopened can of American soda. Then, with a puzzled glance from her husband, who just stood and stared down into the bowl, she untied a narrow wooden box from the top of the packhorse, digging a recess for it so that it was shaded. She pulled away the cloth that covered the top of the box and Shan saw that it was perforated with holes. Deacon's insect singers.

Marco took over like an officer instructing his troops, moving them all down into the shadow of the dune, on the opposite side from the bowl. No one was to go on top, in plain sight, except Kaju. He sent Jowa with Gendun and Lokesh even further, to a place two hundred yards to the north where a small outcropping provided some cover. If anyone came for the boy, the Eluosi announced, he and Sophie would grab the boy and take him into the soft desert sand where trucks could not follow.

Twenty minutes later, at the far end of the bowl, where it flattened and opened into the desert, three figures came into view, riding horses, less than a mile away. Lying flat at the crest of the dune with the binoculars Shan could see that it was two men in the garb of herders and between them, on a pony, a boy. Two large mastiffs ran on either side of the horses.

"Micah!" the American woman called out, and stood as though to run toward the distant figures.

"Warp– no!" her husband yelled, and pulled his wife back behind the dune.

In the same moment, over the dune on the opposite side of the wide, sandy bowl, a vehicle appeared. Not a red Brigade truck as Shan had expected but one of the sleek black utility vehicles of the boot squads. It inched to the top of the dune and stopped. A figure in a red nylon jacket climbed out of the driver's seat. Even without the binoculars Shan knew it was Ko Yonghong.

"The bastards," Marco spat at his side as the remaining doors opened. Two men in grey uniforms, carrying submachine guns, darted half a dozen paces in opposite directions to flank the vehicle, then each dropped to one knee, guns raised, as if prepared for combat. A third man, a barrel-chested figure who walked with a swagger, moved to Ko's side. Major Bao.

A gasp escaped from Kaju, standing halfway down the dune below Shan. The Tibetan stared in disbelief, glanced at Shan with an anguished expression, then looked back as one more figure emerged, a tall, thin, older man with an imperious bearing. Ko solicitiously handed him a pair of binoculars and the man studied the approaching riders, then patted Ko on the shoulder. Shan studied the stranger with his lenses. He had seen him before, in the photograph at Ko's office. "Rongqi," he heard Kaju gasp. It was the general himself, come to witness his ultimate triumph over the Tibetans.

"Dammit, No!" he heard Deacon's urgent whisper from behind, and he turned to see Lokesh and Gendun walking toward the end of the dune, as if to intercept the riders, waving them toward the outcropping as though it might hide them from the men in the truck. Shan felt a hand on his arm. Marco pointed silently toward the entrance to the oil camp, where another car had appeared, a Red Flag. It stopped and backed up, out of sight, then Prosecutor Xu appeared, alone, aiming a pair of binoculars toward the black truck.

Bao's attention was fixed on the riders. He raised his hand and seemed to snap out a command. The two knob soldiers sprang back to the truck.

"No!" Kaju moaned. He stumbled forward, his face twisted with pain. His eyes moved from the riders to the truck and then drifted back into the center of the bowl, where the single shrub grew between him and the truck. He stared at it curiously for a moment, then he began tearing at the neck of his shirt. He pulled a chain from his neck, a chain holding a large silver gau.

Raising the gau over his head, he leapt forward, bounding down the side of the dune, calling out, shouting Ko's name, then shouting for Major Bao, running hard toward the center of the bowl as if trying to meet the truck there. The men at the black truck stared at him for a moment, then jumped into the vehicle, the soldiers leaping on the sideboards, guns still at the ready, as Ko drove over the crest of the dune.

As he ran Kaju kept gesturing with an emphatic energy, as if he urgently needed them, dangling the gau as if they should recognize it. As if it were the Jade Basket. His pace slackened as he approached the bush, stopping for a moment thirty feet away from it, then starting again with a much slower movement, still waving the truck toward him.

Suddenly Shan understood. "No!" he gasped and began to rise. But a beefy hand settled over his shoulder. Marco pushed him down.

"You don't understand-" Shan protested. "He remembers the shrub. He saw the roots before! Deacon!" he called out desperately. The American would know.

Kaju had arrived at the bush and stopped, in the center of the bowl, still waving desperately as the truck sped forward. For a moment he turned, and looked back, as though seeking Shan, then he lowered himself into the lotus position, the gau now clutched at his chest, his head raised not toward the truck but toward the sky.

Deacon appeared at Shan's side. "Jesus!" he bellowed. "No! The cistern!"

The truck lurched to a stop beside the Tibetan and the soldiers jumped off. As the doors opened the truck began to sink and the soldiers shouted frantically at the men inside, one stumbling toward the door where the general had climbed in. Then the soldiers themselves began to drop as if being consumed by the sand itself.

It seemed to happen not in slow motion, but in fast motion, in a blurring sequence, as the desert opened up and swallowed the vehicle into the depths of the ancient cistern, then the sand of the bowl and the adjacent dunes swept inward in a great violent surge. A deep crater appeared for an instant where the huge cistern had been built centuries before, and Shan thought he saw arms and legs swimming in the sand and rock rubble. Then the desert filled the crater, the dunes shifting and sliding with a dreadful hissing and swirling as the tons of sand moved in.

Then, abruptly, there was stillness.

Deacon stood beside him. Shan had not had time to rise from his knees. At the road Xu stood staring, the binoculars at her side, then slowly she disappeared from view, walking backward, still facing the empty bowl. A moment later Shan heard the engine of the car as she drove away.

They walked silently, in shock, toward the shallow depression that marked where the cistern had been.

"We have to dig!" Abigail Deacon shouted repeatedly as she leapt down the dune and began scooping the sand with her hands.

"It's forty feet at least, Warp," her husband said quietly, as he and Shan reached her. "Thousands of tons of sand. Not a chance."

They stood, paralyzed, for a moment as the American woman, still kneeling, pounded the sand forlornly. The desert had claimed more dead. The karez had become a tomb after all. Ko who worshipped money. Rongqi who worshipped power. Bao who worshipped force. And one Tibetan who, however wasted in life, had been steadfast in his death.

A horse whinnied and they looked up to see the riders standing beside their horses now, with Lokesh and Gendun. They did not advance, but stood two hundred yards away, as if frightened.

"Micah!" the American woman called out, and jumped up to move toward the figures. Deacon started after her but stopped and looked back uncertainly as Shan called his name. Shamed by his weakness, Shan handed the American the gau he had taken from Malik, the gau from the grave at the lama field. The American's face went stiff, and his arm drooped when he reached for it, as if it had lost its strength. Shan pushed the gau into Deacon's hand and stepped away. He remembered the stab of pain in his heart when he had opened it the first time, the only time, the day after Malik had given it to him. For inside there had been no Jade Basket, no secret prayer. There had only been the shriveled remains of a small brown cricket.

The American woman kept stumbling in the soft sand, calling her son's name even as she fell. Deacon stood a moment staring at Shan, then at the short, slender figure with the two herders, his face growing dim, as if a veil were descending over it. Then he made a gasping sound as though he were back in the suffocating karez and stepped forward, calling his wife in a voice no one could hear at first, then louder, until as she stumbled to her knees again he caught up with her.

There was no need to explain, Shan saw, for Jacob Deacon understood. The American had been glimpsing another of the nightmares that had shadowed Shan since the nadam. Two mischevious boys had fooled their foster parents, their shadow clan guardians, because one had wanted to move to the lower pastures to be with the horses, while the other had been trying to reach the high Kunlun, the land of the lama field. Khitai had already played the same innocent game by trading places with Suwan at the Red Stone camp. Only for a few days, Khitai and Micah would have said, for everyone would meet at Stone Lake on the full moon. Malik had been certain Khitai died at the lama field but Malik had seen only a battered boy with dark hair already in his shroud, in possession of Khitai's belongings, at the place he expected Khitai to be.

"Micah!" the American woman called again, when her husband pulled her up from the sand. "Our boy!" she cried to her husband, as if Deacon did not understand. But Deacon held her from the back, his arms locked around her, as she faced the riders, keeping her there as Shan and Marco passed by, their pace slower and slower as they approached. The two herders, holding the horses, looked at the Americans with wild, confused expressions.

When they reached the horses Lokesh was sitting on the sand with a slim Tibetan boy, chanting a mantra with him, pointing out the possessions that he had recovered for him at the lama field. Tears ran down the old Tibetan's cheeks.

Gendun stood, his eyes wide and sad, looking from Shan to Khitai and back to the Americans. "Thank you, friend Shan," he said, his voice cracking. "For raising our Yakde Lama from the dead."

Chapter Twenty-Two

No one discussed staying at Stone Lake. But stay they did, for hours, Shan staring in silence at the shallow depression that marked the tomb, Deacon and his wife alone with their grief, Marco introducing the boy lama to Sophie and offering him a ride. Fat Mao came to find Marco and left after speaking with Jowa, taking the Americans to the grave at the lama field. By midday people began to appear, Kazakhs and Uighurs mostly, some on horses, some walking down the road from the highway. They gathered around the depression in the sand with puzzled expressions. Shan heard someone point out the holy man in the robe, and many nodded, as if Gendun's presence explained everything. They raised a small cairn at the site of the collapsed cistern, using rubble from the oil camp buildings and stones from the old ruins. Shan and Jowa removed the prayer flags from the building frame where Kaju had erected them and fastened them to the cairn.

The boy lama seemed to avoid Shan at first, then finally came and sat beside him as he contemplated the bowl of sand that had become Kaju's grave. The boy appeared about to speak, and Shan leaned forward as if to say something himself, but neither of their tongues found words. They sat silently, for an hour, then the boy moved in front of Shan and slowly lifted Shan's hand. He spread Shan's fingers to make an open palm, and then placed the palm over his heart.

When the boy raised his hand Shan reached inside his shirt and pulled out his gau. "I met one of the old ones at Sand Mountain," he said to the boy as he opened the gau. "Before he returned to the sand he gave me this," Shan explained as he pulled out the feather. He stared at it, cupped in his hand. "I gave him a new one, to take back." Shan looked up to see the boy lama staring reverently at the feather, and he extended his hand toward the boy. "I want you to take it now."

The boy did not take the feather at first, but pulled his own gau from his neck, opening the finely worked silver filigree lid to reveal a similar filigree worked in jade. He lifted the top of the Jade Basket and Shan dropped the feather into it.

The Yakde stared at the feather, his eyes filled with emotion. "Micah loved owls," he said softly. "When we were together we would stay up and listen for owls. He had learned from his shadow clan how to call to them. One night he grew very still and said there was one old owl calling for him now, that it felt like the owl was trying to call him somewhere." The boy shook his head slowly, then gently lifted the box close to his face to study the feather. "It will become one of the treasures," he said.

He meant, Shan realized after a moment, that it would become a permanent part of the Yakde Lama's chain of existence, one of the treasures that would become an indicator for future incarnations of the Yakde.

By late afternoon the Maos returned with two trucks, and spoke again in hushed tones to Jowa. They helped Shan and the Tibetans into a truck, then loaded Sophie into the other. Shan jumped out at the last minute and climbed in with Sophie and Marco. They looked at each other without speaking, stroking Sophie as the truck lurched down the road.

"Where will you leave her?" Shan asked. "When you go across the ocean."

Marco's face still had no cheer but it seemed to have found a certain peacefulness. "Leave her?" The Eluosi grunted. "Sophie never leaves me. She goes, she always goes."

"To Alaska? They don't have camels in Alaska."

"They will now," Marco declared in a loud voice. "We'll take her on a big ship, one where we can walk with her on the deck. You and me."

It was such an impossible thing that Shan wanted to laugh. But it was an impossibly wonderful thing. He was young enough to start a new life. Jakli had given him the medallion because she too wanted him to go. Tibet, the lamas always told him, was the starting point for his new incarnation, but no one could know where it would lead. He had missed the trip to Nepal and the new life in England, but now another path was unfolding.

They were close to Yoktian, Shan saw, and suddenly they were passing a familiar set of hills on the edge of the town. At the top of a hill was a boxy black car. Shan pounded on the window for the truck to stop, then jogged up the hill, past the empty Red Flag.

He spotted her in the middle of the cemetery, slowly sweeping a grave with a ragged broom, dust on her clothes. She could have been a groundskeeper or a mourner.

Xu showed no surprise at seeing him and continued sweeping around the grave before speaking. "Glory Camp is dead," she said, huddling over the broom. "Can't use it after the accident, not for weeks at least, probably not until spring." All the prisoners sentenced to six months or more were being transferred to other facilities, she explained, all the others released.

"And those taken by Bao?" Shan asked.

Those too, the prosecutor confirmed without looking up, then she walked to a bag by a grave ten feet away. She pulled out a videotape and tossed it toward Shan's feet.

"I told Loshi to get it, to make them get it back for her. I told her she was fired if she didn't get it, because she had tampered with an official file, that she'd never have a chance for a transfer back east. I was going to bury it." She kicked it closer to him, then, as if impatient with his indecision over touching it, smashed it with her foot. An end of the loose tape broke free of the cassette and the wind grabbed it, unwinding it with such force that it broke when it reached the end. The tape slithered across the graves like a snake, then blew out into the desert.

"They've all been reported missing by their offices," Xu said stiffly. "Someone said they saw Bao pick up Ko and the general at the Brigade compound, in one of the boot squad trucks, but no one saw them afterward. This afternoon the knobs from Kashgar took a look at the Brigade offices. Found a storeroom of contraband. Smuggled goods. Someone said maybe they caused the accident at Glory Camp, to cover up evidence." Nikki's goods, Shan thought. The goods they had stolen from Nikki when they seized his caravan would condemn them.

"People could be convinced that they fled," he suggested. "That they were corrupt and ran in fear of being discovered."

She sighed. "There're campaigns for that too," she said with a slow nod, holding the broom tightly, as if it were all that kept her from blowing away. "Must have fled to America. Everyone knew Ko liked American cars." She appeared much older than her years. She had bags under her eyes, as if she had not slept. "The Poverty Scheme won't stop," she said with a tone of apology.

"I know."

"But those horses, they're too much trouble. We're not going to round up the horses again." She bent with the broom and swept some more.

"There was a hatmaker," Shan said to her back, and found he had trouble swallowing, "who loved those horses."

Xu halted and slowly turned. "Apparently," she said with a frown. "I read the reports. She went north, to a coal mine prison."

"Maybe a mistake was made," Shan suggested. "Maybe she was helping you in your corruption investigation, helping prove that Bao killed Sui over money. You still have Sui's body to explain and the morgue can testify that Bao falsified records." It would be a solution. Not perfect, but he had never known justice to be perfect. Sui could become a posthumous hero, killed by those he was investigating for corruption.

"Just a hatmaker," she said in a near whisper, with her distant look. "What does a hatmaker know about mining coal?" She frowned again, then sighed. "I couldn't just have her freed. Everyone knew she was breaching probation. It would be a transfer to a lao jiao camp. For a few months."

Shan nodded, and she grimaced, then nodded back as if to seal an agreement.

She fell silent, then continued sweeping. He watched her work. She seemed to have grown smaller. "If I had a letter from the Chairman," he said after a moment, "a letter about killing monks, I think I know what I would do with it."

She stopped and looked back at him.

"I would write a reply on the bottom of it," he explained. "Maybe I would say it was wrong what I did, and wrong for you, Comrade Chairman, to pretend it was good to kill monks. Maybe some night I would go alone out to the place where the Tibetan died today and I would light a fire of fragrant wood. Then I would burn the letter to send it to the Chairman, and watch the ashes fly away to the heavens."

Xu stared at the ground by Shan's feet. "It wasn't Kaju's fault," she said in her distant voice. Then she raised her broom and swept again. "There's a little suitcase," she said after a moment. "We found it in Rongqi's room, like it was packed to take back to Urumqi." She gestured toward the bench on the hill above the cemetery, and said no more.

When he said goodbye, she only nodded without looking up. He stopped on top of the hill and looked at her small, bent figure among the neglected graves, the empty desert beyond, slowly moving along the long, desolate landscape.

He found the suitcase beside the bench and opened it. It was a sleek, black leather case with an Italian label, and inside were Rongqi's trophies, the proof he had required for payment of his bounties. Four small, dusty, tattered shoes.

***

The Maos drove south, through Yoktian, onto the main road into the Kunlun. Marco talked with Sophie about the long trip they were to make, then talked with Shan about how they might cook all the fish they would catch. They stopped unexpectedly, behind the first truck, which was pulled to the side of the road. Jowa and Fat Mao were talking to a group of mounted Uighurs. Some of the prisoners from Glory Camp had passed the riders on the way home, they reported. There would be celebrations in the hill camps that night as Uighur families were reunited. Kazakh prisoners, Fat Mao added, were rushing to join the clans now dispersed by the Poverty Scheme. The Maos would see that they found their families.

An old man from the rice camp had been walking up the road into the mountains, one of the riders added. He had been offered a ride in a truck but declined, the man explained with a laugh, because he said he had to watch a butterfly.

Jowa darted to the rider's side. "Where?" he asked urgently.

The Uighur shook his head with a grin, then stood in his saddle and pointed. On a ridge half a mile away a tiny figure could be seen, walking hurriedly through the high brown grass.

"Crazy old-" the Uighur began, but broke off, open-mouthed. Jowa was gone, leaping through the grass running toward the distant figure. In the back of the truck, Lokesh began to laugh. Fat Mao called out that he would send one of the trucks back before dusk.

In the late afternoon they arrived at a small cabin a hundred yards from the road, surrounded by a grove of poplars. It was a surprisingly busy place, with the cheerful noise of boys. Half the Red Stone clan had already passed through, Fat Mao explained, and would be at the silo sanctuary by nightfall, where they would meet Marco and the remainder of the clan the next day. Six of the zheli boys, Jengzi, the Tibetan, and the five surviving Kazakh boys, had been left at the cabin with Akzu and the others. The boys were listening attentively to Malik, who was trying to arrange a game of baseball.

Fat Mao looked at Jengzi. "I know of two dropka at the silo," he said to Shan. "They buried a boy named Alta."

Shan smiled, remembering the forlorn words of the herder the day the man had found them hiding in the rocks. All they had wanted was to have a son and live in peace. They needed a son, and Jengzi needed parents.

Shan surveyed the clearing by the cabin and its jubilant population. The stout woman from town was there as well, cooking a giant pot of stew and baking stacks of nan bread, assisted by Akzu's wife. The Yakde Lama was watching from the trees, his eyes clouded, staring at the opposite side of the clearing. Shan followed his gaze toward a path through the trees. He quietly followed it past the small stream that ran by the cabin to a ledge with a long, high view to the desert. He was about to step onto it when he saw the Americans sitting there, holding each other, Micah's mother still weeping. He backed away without speaking.

At the meal, before the food was served, the two women who had cooked it made an announcement. They had decided that the surviving zheli boys would go with the Red Stone, as well as the stout woman who helped the Maos. The woman looked at Shan as the news was told, and nodded, as though she were apologizing again for what she had done to him in town. He smiled back, remembering what she had said, that she had lost her two sons to Chinese. Akzu stepped close to the fire, his face drawn, as if he were in pain. He had been that way, Shan suspected, since Jakli had been taken. His wife had not consulted him, Shan saw from the surprise on the headman's face.

The leathery old Kazakh looked from boy to boy and shook his head. "It's too dangerous, to go out with us," Akzu said, looking at his wife now. "And much hardship after that. I have buried enough children. They can go to the Chinese school. At least they'll be alive."

"With so many new sons," his wife replied in a strong, proud voice, "Red Stone can become a clan again."

Akzu stared grimly and shook his head again. "Woman," he began, then broke off as two figures appeared from the path by the stream, a woman and a boy. Shan saw in Akzu's face the same confusion he himself felt as he stared at them. They were strangers, but somehow familiar. The boy, smiling brilliantly, led the woman forward until they were a few feet in front of Akzu. The woman stepped behind the boy and began to gently stroke his head, with the serene affection of a mother.

Akzu gasped and looked at his wife, then turned away a moment and wiped his eye. As he did so Shan recognized the two figures. It was Batu, a clean, happy Batu in fresh, bright clothes, and the crazy woman who had thrown stones at Shan. But she was crazy no longer. Her hair was washed and neatly braided, her dress free of the debris that had clung to it, and her eyes were no longer wild, but filled with hope and love for her new son. Malik, staring in disbelief, dropped the ball in his hand. The woman stepped forward to retrieve it, and tossed it to Batu, who caught it and laughed. It was a simple thing, a small sound of joy, but somehow it resonated through the clearing, drawing the attention of everyone there. Because, Shan realized, it was just a boy sound, a sound not of a tormented youth who had been running from killers but the sound of a child, and perhaps of an entire clan, learning about joy again.

The clearing was silent. Every eye fixed on the headman as he solemnly looked into the faces of each of the orphan boys. "It's going to take a lot of new saddles," Akzu declared at last, and his wife rushed forward to embrace him.

After the meal, when the sun had been down two hours and most of the camp was asleep, Shan went back to the ledge. Deacon was there alone, under the full moon. Not quite alone, for he had his singers with him, arrayed in a semicircle in front of him. Shan did not join him at first but returned to the cabin to speak to the Yakde Lama, then ventured back to the ledge.

The American did not speak when Shan arrived but moved to the side to make room for him.

The moon was so brilliant they could see the glow of the desert miles away. One or two of the crickets sang, uncertain chirps, as if frightened perhaps.

"There was a compass there," Shan said quietly. "A black metal compass." He reached into his pocket and handed it to the American.

Deacon took so long to reply that Shan thought he had not heard. "I gave it to him. He was brave and independent, but that day he first left with the zheli he asked where we would be. I told him and said we would always be there waiting for him." Deacon's voice cracked and he stopped speaking for several long moments. "I said, Take my compass, and I showed him on a map where Sand Mountain would be. So if he ever wanted to talk to us or shout out goodnight he would know which direction to face."

Shan closed his eyes and fought away the image of the terrified boy as Ko came for him with the bat and knife, pulling out the compass to know which way his parents were, which way to go to find safety.

They were silent again, for a long time. More crickets sounded. "Ironlegs won't talk," Deacon said absently. "Never has, since that night I caught him." The moon rose higher and brighter. From somewhere an owl called. And then, behind them, a twig broke. The Yakde Lama stepped into the moonlight, looking down, wearing a sad, shy smile.

"There is someone I want you to meet," Shan said.

"I know Khitai," Deacon replied in a hoarse voice.

The boy took a step closer.

"There is someone I want you to meet," Shan said again.

The boy took another step forward.

"You said you were going to buy a bicycle for him," Shan said.

The American made a choking sound and then a sob wracked his broad shoulders. He put his arms out, the boy ran forward into them, and the American finally cried. In long groaning sobs he cried, and the boy clung to him and cried too. Until finally they began to quiet. Because all the crickets were singing.

***

He was awakened by a light touch on his shoulder, just as the sun was rising. "Is it true," Gendun asked in almost a whisper, "that the Yakde still wishes to go to America?" Shan only nodded, and Gendun rose and moved back to a small group sitting by the trees. Shan threw his blanket off and rose. The camp was still quiet except for two Maos at the fire who had been on guard all night. He walked to the trees. Gendun, Lokesh and an old, nearly bald Tibetan were listening to Jowa as he drew with his finger in the earth, a map of how to go from Senge Drak to the Raven's Nest. Shan looked back to the stranger and froze.

It was the waterkeeper. The old lama seemed to sense Shan's stare. He looked up and nodded warmly, then patted the earth between himself and Lokesh, inviting Shan to sit. As Shan returned the waterkeeper's smile he remembered the lama's last words to him. There has to be a crack or nothing can get in, he had said at the clinic. In the end, that was all Shan had been able to do, to help open the cracks, first in Kaju, and then in the hard brittle shell around Prosecutor Xu.