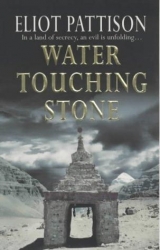

Текст книги "Water Touching Stone"

Автор книги: Eliot Pattison

Жанр:

Полицейские детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 11 (всего у книги 38 страниц)

"We were friends, Lau and me. She was the only one who ever sat in the front of the car with me. She used to bring me medicines, and she gave me special teas from herbs she found in the mountains." Wangtu pointed for Jakli to look back at the white horse, as if it might comfort her. "Things were happening to her. Fired from the Ag Council. The report to Public Security." Jakli turned away now, looking at the faces of the other prisoners. "That Tibetan," he continued, to her back. "I told her about that Tibetan."

Jakli spun about.

"Kaju. I didn't know his name then, but I told her, maybe three months ago, about the Tibetan Director Ko was bringing for the zheli. She didn't know. I told her I heard Ko talking in a car one day, I said to her I guess they think you're leaving."

Three months ago, Shan remembered, was when Lau had begun explaining where she wanted her body taken. "What did Lau say?" Shan asked.

"She just smiled at first and patted my arm. Then she said yes I guess they do, and she sighed and said she never should have gone to Urumqi. She always talked with me, but that day she was just quiet until the end of the trip."

"Gone to Urumqi?" Shan asked. "What did she mean?"

"I never knew," Wangtu shrugged. "Some trip to the capital."

"What else did she say?" Jakli asked.

"When she left that day she said maybe she shouldn't bring me teas anymore, that later people would say we were friends because of it. She said we could still be friends in our hearts but that she wouldn't want me hurt because of it. I said I don't care what they say, and she said you have to care, because this is China." Wangtu looked back at the white horse with a pained expression. "After that she always seemed to be in a hurry, no time to talk. I didn't drive her much afterward. Haven't seen her for a month." He shifted his gaze toward the horizon with a thoughtful expression. "Where she died, who was there?"

"That's what we want to find out." Jakli said.

"No. I mean, who did she go see? It's important. Lau, she had only certain people she trusted. She would only stay where one was close. She moved from one to the other, like from one oasis to another. Where she went, you should ask them there."

Shan and Jakli exchanged a glance. Lau had died in the place in the desert which Jakli seemed unwilling to speak about, the place where Bajys had his nightmare vision of dismembered humans.

"The prosecutor," Jakli said. "The prosector doesn't know," she reminded him.

"All I know," Wangtu said with a forced grin, "is that she didn't know how to swim." He cast a hopeful glance toward Jakli. "I wouldn't tell all this to anyone. But I did to you, Jakli."

Jakli looked at him in obvious discomfort. "I am getting married, Wangtu," she announced quickly, then leaned forward, kissed his cheek, and stepped away toward another prisoner she seemed to have recognized.

Married. Shan gazed after Jakli, feeling foolish for not having understood before. The hushed, excited conversations at Red Stone camp. The dress being whisked away by the older women. Malik's secret gift for Jakli and someone else, whose name the boy was reluctant to speak. Nikki, the name Akzu had mentioned when parting from her at the garage. Other women would have joyously shared the news. But Jakli's marriage was wrapped in secrecy. Shan understood, for he too had grown up in a world where you said the least about the things that were most important to you, for fear that they would be taken away.

Wangtu stood, crestfallen, as he watched Jakli begin talking with a short plump Han man. "You have to keep her out," he said, then repeated the words more urgently, as if Shan might not have heard.

"Out?" Shan asked. Shan looked at her again. What an odd time to be getting married, when the clans were being disbanded, and children were being killed. But Shan had learned years ago how difficult it was to translate the language of another's heart.

"Out of Glory Camp. Out of prison. Some of the guards hate her because she talks back to them, because she resists. She's not made for a cage. Like the Mongol boy." His disappointment seemed to have turned to worry. His mouth opened again but no words came out. He looked to Shan and then to the ground. "I would have done her time for her if I could," he said quietly. "She belongs in the mountains, on a horse." Then he drifted away, as if he had forgotten Shan stood there.

"Comrade Hu," Jakli said as she brought the short Han toward Shan. "Chairman of the Educational Committee for the school in Yoktian."

Hu touched his thick-rimmed glasses and gave a shallow smile. "Former Chairman, I guess," he said.

"Not necessarily," Jakli said reassuringly. "It's just Prosecutor Xu's way, to intimidate witnesses."

"I told her," Hu said. "I witnessed nothing. Lau was not on our official staff. We had no official responsibility for her. Once she received a small stipend but that stopped years ago. We just gave her an office, let her know our schedules so she could coordinate. Let her use our drivers sometimes."

"So you spoke to Xu already?"

"This morning. She told me to think about it, after I said I knew nothing. Good jobs are hard to find in Yoktian, she reminded me. She looked at my file and reminded me that I have a family. I told her there were no secrets about Lau. She was an open book. Maybe too open. That's all it was, she was too blunt with the wrong person. Some of the herders have tempers, some still have one foot in the age of the khans, when there were blood feuds." He looked over the prison grounds. "I offered to instruct classes while I was here," he declared, as if he suspected Shan might be a political officer.

Shan's attention drifted away. Comrade Hu, he had quickly decided, was not the type that Lau would have confided in.

He sensed that Wangtu was right, that Lau was someone with great intuition about people, who moved from one she trusted to another she trusted. But what did she leave with them? Secrets. Secrets are what you give to those you trust. She had gone to the place in the desert, to the place called Karachuk, not to die but to share a secret.

He noticed another man, sitting in the shadows against the wall of the mess hall, facing the open yard of the camp but casting occasional glances toward Shan and Jakli. He was nearly bald and had so little flesh on his face that the contours of his skull were unmistakable.

His eyes made momentary contact with Shan's, and as they did so his eyelids seemed to droop and his fingertips touched the ground, as though the man had grown sleepy.

"A waste of time," Jakli declared as she followed Shan's gaze. "Go ahead," she said with a shrug, "but you'll make no sense out of what he says."

Shan cast her a puzzled glance as she continued to speak with Hu.

"The Xibo," she said in an aside to Shan. "The waterkeeper."

"What's his name?"

"I don't know. He's always just the waterkeeper. He just mutters nonsense and drools. He speaks only the tongue of the clans and the old Xibo words."

Confirming that Jakli remained occupied with Hu, he stepped toward the bald man.

The waterkeeper gave no acknowledgment when Shan squatted in front of him. He just shuffled sideways, as if Shan had blocked his view. Shan matched his movement, then sat on the ground. The two men said nothing. Shan stared at the waterkeeper. The man stared over Shan's shoulder as if not noticing him, sucking something, perhaps the shell of a nut, or a pebble. A thin line of drool hung from the corner of his mouth.

Shan had spent his childhood in Manchuria. He had known Xibos, and the man in front of him was no Xibo. Nor was he in his fifties, as Jakli had indicated. He was older, perhaps much older, though only his rheumy eyes and the rough yellow ridges on his fingernails showed it. The man looked down at the dirt in front of him and made a grunting noise, an old man's noise. But Shan believed none of it. Not the absent, drooping eyes, not the drool, not the muttering.

It was the fingers he had noticed first, while still standing by Jakli. The fingers weren't just drooping down, they were carefully aligned, with the left hand flat in the lap, the right draped on the right knee, palms inward, fingers aimed down, thumb slightly apart. It was a mudra, the Earth Touching mudra, invoking the land deity, calling it to witness. And between the fingers of the right hand was a small dried flower.

There was a connection Jakli had apparently overlooked. The waterkeeper was hired by the Agricultural Council. And Lau had served for years on the council.

Shan began arranging his own fingers carefully, in a fashion he had learned in Lhadrung, with his hands cupped, pressed together, the fingertips touching, the thumbs pressing against each other.

The waterkeeper's eyes drifted, passing over Shan again as if he were not there. The last of the bags for the kitchens was unloaded, and the men began to bunch up near the stairs, watching the loudspeakers as if expecting new instructions.

Shan did not move. He fixed his eyes on those of the waterkeeper.

Finally the man's eyes found Shan's hands. His head made a quick, trembling motion as if his mind itself were blinking. With one glance Shan understood. The man saw what Shan had made, a mudra, the mudra of the Treasure Flask, the sign of the sacred receptacle. He saw what it was, and he saw that Shan knew he had seen.

The hoods over the waterkeeper's eyes slid away. His eyes did not move in their sockets, but his head rose slowly until he met Shan's gaze.

"I have been to your cave, Rinpoche," Shan whispered in Tibetan. "I am going to help you. I am going to help the children."

The waterkeeper did not reply, but after a moment took Shan's hands and squeezed them slowly, but hard. "Even if you find the one, you can't take it back." The words came so suddenly, in Tibetan, and in such a low, whispered voice that Shan almost thought it was only in his head. But the man's moist eyes grew wider, and his mouth moved again. "You can only take it forward," he said hoarsely, and his eyes shifted toward the mountains, towards the Kunlun and Tibet.

The memory of Bajys's words flooded over him. That was the one I loved, he had said of Khitai, as if there were many Khitais. That was the one I was to keep safe. Bajys hadn't understood, or if he had understood, hadn't cared, that Khitai was still alive. What had broken Bajys, what had sent him fleeing, whimpering, raving, toward Lau was a broken trust. Someone had discovered a momentous secret, Bajys' secret, and because the secret was known, Bajys's world was ending. Now the teacher, the old lama who was the waterkeeper, was speaking in the same riddles. Maybe Bajys had not been speaking of a boy after all, but of an object. You can't take it back. You can only take it forward.

Suddenly the truck engine roared to life. The old man rose, his eyes assuming their drowsy, half-wit glaze again. He stumbled over his own feet as he headed toward the mess hall. The prisoners at the door laughed at him.

An instant later the loudspeakers crackled to life again. The men gathered around the mess hall and straightened their tunics, then started moving into the throng of prisoners that began filling the yard. It was their turn to be blessed by the political priests.

Moments later Fat Mao eased the truck past the inner wire. But as they tried to leave Glory Camp they found the main gate secured with a chain and padlock, no guard in sight. They waited nervously for ten minutes, then Fat Mao inched their truck toward the administration building. A figure emerged, not a guard but a Chinese clerk in a white shirt frayed at the cuffs.

"You were told what to do," the man said in shrill voice. "The rest of the cargo is unloaded tomorrow."

"So we will be here tomorrow," Fat Mao said. "At dawn if you wish."

A sneer rose on the clerk's face and he unfolded a slip of a paper from his pocket. "We are authorized to receive one shipment a week," he squeaked. "You are authorized to be paid for one shipment a week. The full cargo was accepted by signature at the kitchen." He waved the paper near Fat Mao's face. "You think you'll come back tomorrow and be paid for two shipments? Not a chance."

"Don't be ridiculous. We only get paid for shipments we deliver."

"Exactly," the clerk said with a victorious wave of his hand. "And you propose to deliver only a half-loaded truck tomorrow." He raised his nose and seemed to point it at Fat Mao. "There are campaigns against corruption."

Shan watched the Uighur's jaw tighten as he tried to control his anger. "Then we will unload the bags on the dock. Tomorrow you can move them inside."

"Your payment is for delivery inside the warehouse. Cheating on labor is another form of corruption," the clerk snapped back.

"So open the warehouse."

"The warehouse is closed by order of Major Bao of Public Security. You have been permitted to use the repair bay tonight." He pointed to a tall structure beyond the office that was nothing more than a high roof supported by four posts, with a workbench at one end. "But I warn you," he added in his shrill voice, "we have a complete inventory of all tools."

"We are supposed to be back with our families tonight," Fat Mao protested. "Our people expect us in Yoktian."

"We all must make sacrifices. That is the essence of Glory Camp," the clerk said happily, as if grateful for the chance to offer political advice, then spun about and marched toward the office building.

Fat Mao stared venomously at the clerk, and then, with a glance toward Jakli, put the truck into gear and drove toward the repair bay. "Campaigns against corruption," he muttered. "How about a campaign against stupidity?"

Shan remembered the knob guard. "He mentioned Major Bao," he said to the Uighur. The Brigade ran the camp, the prosecutor kept it filled, but the knobs apparently used it at their convenience.

Fat Mao grimaced. "Head of Public Security in Yoktian. Lieutenant Sui's boss. The two people you never want to cross in this county are Major Bao and Prosecutor Xu."

The Uighur and the Kazakh men rearranged sacks of rice in the cargo bay into makeshift beds and immediately laid down to sleep. Shan stepped toward Jakli, who stood by one of the posts supporting the roof, staring toward the prisoner yard.

"I never expected this. I'm sorry," she said. "Jowa spoke to me at Lau's cabin. He told me they were working on a way out for you, out of China, that there are people at the United Nations who would take care of you once you crossed the border. I wasn't thinking. That kind of opportunity never comes for most of us. We never should have asked you to take this kind of risk."

"It's just kind words they speak to me sometimes," Shan said. "Just their way of giving me hope. It will be years. Most likely, it will never happen." He stared toward the mess hall where he had last seen the waterkeeper, then toward the barracks with the wire windows, the special holding cells. He had forgotten to ask the waterkeeper a question. Did he know Gendun? "And no one forced me here," he added, trying to force a smile.

Jakli shifted her gaze back toward the prisoner yard. Not the yard, Shan saw after a moment, but the wire, or the rope corral adjoining the wire. "There used to be more horses," she said in a sad tone. "They take horses in trains to the east from Kashgar now. There are factories there that do nothing but kill horses. They put the meat in cans. So the government can boast about how well the people are fed. Now they want all the herds, even the wild ones."

Jowa had been right, Shan thought. The Poverty Scheme was a liquidation program. In the name of liquidating inefficient assets, the government was liquidating the entire nomad way of life. A private, politically correct scheme for achieving the final stage of what Beijing had started decades earlier.

"Why a white horse?" Shan asked.

"White horses are for gifts."

"Wedding gifts, you mean?" Shan asked, turning to look her in the eyes.

"Not only weddings. Namegiving days. Special festivals," she said shifting her gaze back toward the horse. "But especially weddings," she added with a shy but determined smile that said she would say no more about the topic.

"And Wangtu talked about Lau reading names from the five twenty-ninth and-"

"And 1997," Jakli finished. "Political demonstrations. The five twenty-ninth means the May 29 uprising in 1962. Kazakhs and Uighurs fought against the government, in Yining. Many were killed. The government never reported the deaths. But we know the names. We honor the names, by reading them out loud at clan gatherings. Then in 1997 there was more fighting. The PLA was called in. Machine guns were used. Bombs went off in Urumqi."

"Was Lau a dissident?"

"Someone who reads the names of heroes to children, is that a dissident?"

"You know what I mean. Was she marked for criticizing the government somehow?"

"No." It seemed to take a great act of willpower for Jakli to turn away from the horse. She pulled a piece of paper from her pocket. "Otherwise, we wouldn't be here. There would be no murder to investigate. There might have been an announcement about a political correction. Maybe a lie about her being transferred. But just no more Lau." She pulled a folded, tattered envelope out of her pocket, then stepped to the cab of the truck and climbed up, as if to read its contents.

Shan realized that if he climbed the remaining sacks of the cargo bay into the deep shadow cast by the roof of the repair bay, he would have a clear view of the administrative compound without being visible from the outside. He nestled onto the sacks at the top and did what he did best. He watched.

The warehouse, apparently usually open, was locked for some reason. There were no windows on the three sides he had observed thus far and only the single set of doors at the loading bay. The compound was quiet. The afternoon classes were in session. The only sign of life came from the boiler building, where several men hauled coal from the pile, and the small shed, where the solitary knob guard stood, occasionally pacing around the structure, sometimes raising and sighting along his weapon toward the horizon. The administration building remained quiet, although the sound of music drifted out of an open window. It was a military march, from a badly scratched recording, played again and again.

He drifted into sleep. When he woke, a new car was parked by the administration building– a Red Flag limousine. The music from the administration building had stopped, but there was no sign of activity from the new arrival. Inside the inner wire a few prisoners drifted around the mess hall. A class sat outside now, around the pole in the center of the prisoner compound that held the red flag of the People's Republic. The door of the warehouse remained closed. The workers at the coal pile still fed the boiler. But the guard at the shed had brought a chair to the front of the structure. He was slumped in it as though asleep, his weapon hanging from the back of the chair.

Slowly, his eyes shifting from the guard to the administration building and back again, Shan climbed down from his perch. Jakli had joined Fat Mao and her cousins and was sleeping, the tattered envelope held between her palms as though she had been praying over it.

He walked toward the warehouse, fighting the urge to run, watching the door by the empty limousine and, in the opposite direction, the solitary sleeping guard. It was indeed locked, but as he pressed the latch he thought he heard a voice.

"Who is it?" Shan whispered, first in Tibetan, then in Mandarin.

There seemed to be a reply, a low sound, but whether it was a word or simply a moan he could not tell.

He could not risk attracting attention. Shan quickly stepped away from the doors and moved around the edge of the building, hoping to find a window in the far end. There was none. He turned to face the boiler house and beyond it, the cemetery. The shed was quiet, the administration building still, the gate unmanned. He set a course toward the shed with the Public Security guard. Thirty feet away, close enough to hear deep snoring from the knob in the chair, he veered toward the boiler house.

A small column of greasy smoke rose from the chimney, drifting toward the mountains. Half a dozen men labored at the mound of coal adjacent to the structure, loading oversized wheelbarrows that they pushed through the open front of the buildng and dumped at the boiler, where another man shoveled the coal into the fire.

The six men were different from the other prisoners. They did not wear the coarse grey uniforms of the men inside the wire, and though their clothes were stained with coal dust, the colors of their shirts and vests were still bright enough to mark them as recent arrivals. Perhaps, Shan considered, they were more of Xu's special detainees. But they seemed somehow different. Wangtu and the others had been given light duties. These men had the hardest labor in the camp, as if they were destined for the harshest fate. But the faces of the men seemed to say otherwise. There was no surrender, none of the bitter resignation to surrendering a piece of their lives to the political officers. They were rough men, thick with muscle, none of them Han. They did not seem to take their labor seriously, as though they could be relieved, or even freed, at any moment. But they expected no relief from Shan. Three of the men glared at him and looked away. The others continued their work while silently frowning at him. Then he remembered the computer data that Fat Mao had shown them. There were other reservations at Glory Camp, for the Brigade, and for the special knob boot squads whose job it was to fight reactionaries and insurgents.

Shan moved into the shadow under the roof and looked back. Nothing had changed. The limousine was still at the office. The knob was still asleep. He studied the building. It contained only machinery, the boiler and the small old turbine generator it powered. There was a workbench with mechanic's tools by the generator. No one else was in the structure except the man at the open boiler door. He stopped, silhouetted by the intense fire, and leaned on his shovel as soon as he noticed Shan.

As Shan nodded awkwardly and ventured a step closer, the man wiped the soot from his brow. Shan froze in confusion. The man's skin was white. The stranger pushed back his filthy cap, revealing a swath of long blond hair. A flicker of interest passed over his face as Shan approached, and with a heavy Western-style hiking boot the man kicked the boiler door shut, muting the roar of the furnace.

"Hello, your excellency," the Westerner said in a mocking tone. He spoke in English, with an American accent. "Did you bring me some tea and cakes?"

As Shan took another step forward a hand closed around his upper arm, a rough painful grasp that pulled him backward so hard he almost fell. Shan turned to look into the face of the beefy Public Security guard, who had clearly awakened in a surly mood. His weapon hung forward from his shoulder, his fingers resting near the trigger.

"No damned access!" the knob snarled. "No one! No time!" he barked, then roughly pulled Shan toward the sunlight.

"Yo!" the tall Westerner shouted in farewell, with a mock salute. "Let's do lunch sometime!"

Shan let himself be led toward the center of the yard, craning his neck to watch the American as the man made an exaggerated shrug of disappointment toward the men at the coal pile, who laughed, then lowered his cap and resumed shoveling the coal.

As Shan turned back to the guard his face tightened in fear. He had not simply been stopped in his investigation of the men working at the boiler, he had been exposed. He was being escorted by a knob. Knobs did not take you where you wanted to go. They took you where Public Security wanted you.

But as they proceeded across the empty yard the guard's resolve seemed to dissipate. His steps became shorter, and he released Shan's arm. He looked at the shed where he had been posted, then glanced back at the administration building and turned uncertainly toward Shan. Suddenly his head snapped back toward the office building. A figure had appeared on the steps of the building, a woman in a black suit. Prosecutor Xu Li.

The guard looked from the woman back to Shan, then spoke nervously. "No one is to go near the boiler house crew, that's all," he said, then brushed the shoulders of Shan's threadbare jacket with a sheepish, deferential look, and jogged back toward his shed.

The woman stared at Shan in expectation. She was waiting for him. She did not need to summon him with a guard holding a submachine gun. Her severe stare was weapon enough.

With a quick glance he saw that no one was stirring at the repair shed. Would he at least be given a chance to say goodbye to Jakli, to get a message to Lokesh? No, he realized, he could do nothing that might implicate Jakli and the others. His mind raced. He would have to say he tricked Jakli and Fat Mao, that they knew nothing about him.

He put his hand on his chest, over the gau around his neck, then took a deep breath and with small steady steps went to surrender to Prosecutor Xu. He let his prisoner's instincts take over, as a way of fighting the cold fist of fear in his belly. Would they take him back to Tibet? Would they send him to the special interrogation place he had visited in the desert? Or would they decide he wasn't worth the trouble and dispose of him right there. At least, a detached voice called out from somewhere in his mind, you'd get a real grave.

As he approached her he studied the woman's spare, stern face. Surprisingly it didn't show the contempt of a jailer for a prisoner. It didn't show suspicion. It only showed impatience.

He was almost at the stairs when she spun about and stepped inside, leaving the door open for him. He followed her.

The interior was like a thousand other government offices Shan had seen. Most of the space was devoted to one large open chamber with two rows of metal desks, the majority of which were unoccupied. A young woman of Kazakh or Uighur blood, her hair bound into two small pigtails, looked up from a computer terminal, then quickly, nervously, averted her eyes. Someone called out a whispered warning, and Shan saw two other office workers scurry away from their desks, toward another woman who motioned them into a back room. As if they had detected volcanic signs in Xu and were expecting an eruption.

Xu Li waited for him at the door of a meeting room, pointing to a chair at a large metal table.

He sat. She stepped to a thermos and poured two mugs of tea, placed one on the table barely within Shan's reach, then sat opposite him.

"I know what you're doing here," she said brusquely.

It was over, before it had really started. Children were still dying. Gendun was lost. The waterkeeper lama was imprisoned. And Shan would never have his chance to help them, nor his chance to leave China. He locked his hands around the steaming mug. There were tricks prisoners played, to endure. Many of them had to do with simply getting through the next moment, not thinking about the suffering to come, only dealing with the present suffering. Had his hands instinctively begun playing the old game, he wondered, fixing on the searing heat from the mug, focusing on one sense in order to evade as long as possible the flood of pain to come? The monks in his gulag barracks had taught him that such concentration was not the best answer, that he shouldn't seek concentration but mindfulness, to steer his mind to a place interrogators didn't occupy. But he had no time to prepare, and if such concentration was the only crutch he could find, he would use it. His eyes lost their focus as he stared into the mug, absently considering how it would be years before he had real tea again if he were being returned to the gulag. Sometimes, when there was hot water, he would put a weed in it and call it tea.

"My name is Xu Li," the woman announced. "From the Ministry of Justice. I am the prosecutor for this county."

Jade Bitch. Shan almost said the words out loud. There was another trick he had learned for interrogations, not from the monks but from the khampa warriors who had shared his gulag barracks. Preempt the fear. Preempt the pain. If they were going to threaten something awful, imagine something even more terrible. If they were going to hurt you, then try to inflict greater pain on yourself. He raised the mug to his mouth and swallowed half the scalding liquid, raising a long stab of pain from his tongue to his belly. He lowered the mug and stared at the prosecutor without expression.

The action seemed to unsettle the woman. She raised her own mug, then put it down quickly as the heat singed her tongue. She frowned. "I know you are from Beijing. I don't know your real name." Her voice was smooth and supremely confident, a voice long accustomed to being in complete authority. "I don't want to know your name."

It seemed impossible. How could she have known his background already? Had he been so careless? Had everything since he arrived in Xinjiang been an elaborate trap?

"Nobody asked me if I approved of what you are doing. No one is going to. It's all Beijing, I can smell Beijing all over it," she added, as if it explained much.

Shan looked around the room. There was a chalkboard on one wall, with a number scrawled near the top. Nine hundred forty-eight, no doubt the number of citizens undergoing reconditioning at Glory Camp. There was a faded poster with a collage of bright young Chinese faces, with the caption Destroy the Four Olds. It had been one of the more enduring campaigns started by the Red Guard many years earlier, part of the insanity that had swept his father away. Destroy old culture, old ideology, old customs, old habits. It had been a particularly intense spasm of pain inflicted on the Tibetans, Muslims, and other minorities. Old books, traditional clothes, and religious artifacts had been consigned to bonfires. Entire fires had consisted of nothing but braids of hair worn in the old fashion.