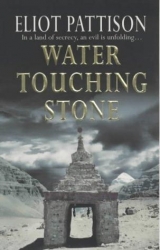

Текст книги "Water Touching Stone"

Автор книги: Eliot Pattison

Жанр:

Полицейские детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 17 (всего у книги 38 страниц)

Shan found Gendun in the room of fragrant wood.

"It is right that you come back with us," the lama said. "This was all a mistake. We didn't understand. We will go to Lhadrung together. We can watch the moon from the truck, like before, and you can go to your new life."

"I have only just begun here," Shan said woodenly. It was happening too fast.

The lama shook his head. "Even without the letter Jowa gave you, you should have gone back south. The thing that dwells below, it's like a cloud that covers a beautiful moon. I have no words for it, except death. But that is too simple a word. If you were lost, Shan, without your soul in balance…" He studied his clasped hands a moment, then looked up with wide eyes. "It would be worse than losing Lau."

"Because she was prepared?" Shan asked.

Gendun nodded.

"Not just prepared," Shan suggested. "She expected it. She expected to die for her secrets." Gendun turned his head toward Shan as if about to correct him. Shan exchanged a long silent look with the lama. "Not her secrets, really," Shan said. "Her faith. She was Tibetan, but not just Tibetan. I think she had religious training. I need to know for certain, Rinpoche."

"It seems you already know, my son."

Shan nodded slowly. "She was an ani, a Tibetan nun."

Shan heard a sound behind him, a small murmur of approval. Lokesh was there, and came forward to sit with them.

Gendun offered a sad smile. "Once she was a nun, but her convent was destroyed."

"I have known many monks who lost their gompas to Chinese bombs," Shan observed. "Some said, Without my gompa, I am no longer a monk. Others said being a monk had nothing to do with a building. An old monk in my prison said it best. I carry my gompa on my back. It's all about serving the inner god, he said, and no bombs can destroy the god within. I think Lau found a way to serve her inner god in Yoktian."

Gendun didn't just look at Shan. He seemed to be watching him, as if something important was happening to Shan.

"She lived a Kazakh life these past years and was buried in Kazakh clothing," Shan continued slowly, "But she asked to be laid to rest near the teaching room of the old lama who posed as the waterkeeper. She taught Jakli the old Tibetan ways. She helped the lama with his secret teaching."

There was another sound at the door and movement behind him. He did not turn as the figure sat beside him. He knew it was Jakli.

"We used to meet on festival days," Lokesh said in a faraway tone. "The monks from our gompa and those nuns. Lau came from a small sect, from a tiny gompa built near a glacier north of Shigatse. We would unfurl a giant thangka down the hillside– a hundred feet long, it was. There would be archery contests and acrobats who climbed to the top of huge poles to bring back prayers tacked to the top. The nuns would sing to us, and we would serve special tsampa we made with cardamom spice." As he extended his long bony hand, spotted with age, toward the lights, Jakli reached out and clasped it between her own, as if to thank Lokesh. Or perhaps comfort him. "Later," he said with a sigh, "people came and burnt her gompa." He began humming one of the old songs as they watched the flames of the lamps, then paused. "It was a long way she went," he added, "to die like that in the desert."

"Now they have sent another Tibetan to teach the orphans," Shan said.

"Is he not also in danger, then?" Gendun asked.

No, Shan started to say, because Kaju works for the Brigade. "No," he said instead, "because the killer already found the orphans."

"You mean, at the camp of the Kazakh clan."

"And after that, the boy we buried by the road. First Lau, because Lau had to tell the killer about the orphans. Maybe," Shan said in a grim voice, "the killer is after all the orphans. The old Kazakh says it is a killer from the old days, returned to destroy the children of his enemies."

Lokesh shook his head, with a tiny, almost imperceptible motion. But Shan noticed.

"Or maybe he asked Lau about one boy, but then that boy was unexpected, was not right," Shan suggested. "The killer tore each boy's shirt open. He tore the pant leg. First with Suwan, then with Alta." He looked at Lokesh, still trying to understand. "He had gone for a boy at Red Stone camp, but the boy didn't have what he wanted. Maybe the killer was looking for something, perhaps something of Lau's that she had entrusted to an orphan. If he had found it, why would he go on to attack the second boy?"

"Maybe," Lokesh said slowly, "the children did something Lau, or her killer, never expected."

Shan looked at his old friend and nodded.

"If it is true, then maybe the demon isn't after all the children," Jakli said. "Just always the next one, until he finds what he needs. Or she," she added with a glance toward Shan.

They stared at the flames. A deep groan seemed to come from somewhere. It could have been the wind. It could have been the mountain, trying to make itself understood.

"You have the solved the mystery of Lau," Gendun said with a slow nod, looking back toward Jakli as he spoke. "That is enough, perhaps. To reveal Lau's secret teaching."

Jakli spoke Lau's name with a sound like a sigh and looked up with a nod. "Her path has been identified," she agreed. "Lau's truth can be told to those who were close to her, to close the circle of her life. She was a secret Buddhist. It should be enough to know that." Jakli looked at Shan and shrugged. "We know who is the enemy of secret Buddhists. I think it will be enough to persuade more herders to protect the zheli, to hide them for the winter at least." The demon was the government, she meant, and no one could stop the government. "It is all any of us can do," Jakli said to Shan, biting her lip as if she were in pain. "Now you can go on to your new life."

Gendun's eyes moved toward the floor and took on the distant look of deep meditation. Lokesh began counting his beads, appealing to the Compassionate Buddha.

The two Tibetans would not hear Shan even if he pressed on with the questions that burned on his tongue. Jakli too seemed lost in her own sort of trance, watching the two Tibetans so intensely she did not appear to notice when Shan rose. He picked up his lamp and wandered out, into the dark, silent corridors of Senge Drak. He longed to see all of the remarkable dzong and regretted that he had only a few hours to experience it. He passed down a long row of tiny rooms carved out of the rock, several with shreds of cloth hanging in front of them. Meditation chambers. He walked for over fifty yards without seeing an end to the rooms, and stopped, awed by the sheer number of the cells. Some fortresses had training grounds for their garrison. Senge Drak had meditation chambers.

He stepped to a cell that had most of its covering intact, slipped inside, and settled into the lotus position with the lamp at his side. He closed his eyes. He might not be able to speak with the mountain, but he could feel its serene power. The suspicion and fears, the possibilities swirled about his mind. He was more confused than ever. Everything was too unfocused. There were too many disconnected people, too many disconnected forces pulling him apart. Someone was going to rescue him, to give him a new life. Everything he needed, Lokesh had said. But that wasn't justice for Lau or her boys. Who would find her killer? Who would save the waterkeeper?

He put his hands in a mudra, the Diamond of the Mind. He had to explain things to Jakli and the Maos, but he did not understand them himself. He had to simplify, to focus on the simple explanations, for they were usually the right ones. Prosecutor Xu hated Tibetans. She was the likely one to have discovered that Lau was a Tibetan nun and, if so, was tracing any of the zheli with Tibetan roots. She or her enforcer had gone to the Red Stone camp and killed the first boy, who had been with Khitai. They said Khitai had no Tibetan roots, but they had said the same about Bajys. Or perhaps Khitai, who had been the first target when the killer had extracted information from Lau, was just a Kazakh boy who had the Tibetan thing that Gendun and Lokesh were so concerned about– Lau's treasure, the thing that now was being passed from orphan to orphan, one step ahead of the killer.

When he opened his eyes he noticed something in the corner, a long piece of coarsely woven woolen that might once have covered a meditation cushion. He lifted it and saw with a start that it covered an artifact of Senge Drak. It was a graceful bow, unstrung. Pulling the cloth entirely away, Shan found a small bowl of camphor wood, carved with intricate geometric designs. He lifted its top and found, lying in a neat curl, a bowstring, exactly as its owner had left it– when? A century ago? No. Jakli had said the dzong had been abandoned for centuries. Two or three hundred years, perhaps. He picked up the bow and laid it in his lap.

He retrieved the covered bowl. There were four rows of repeating designs, two on top, two on the bottom. He and his father had passed many hours exploring the Tao te Ching by using throwing sticks or dice to randomly identify verses. But their favorite method was finding patterns in their environment and reading the patterns to derive tetragrams, the four line combinations that, in the charts memorized by all students of the Tao, referenced one of the book's eighty-one chapters.

Shan counted by sixes along the top rows of tiny triangles. After the final set of six, three remained. Three was represented by a broken line of two parts in the system, the base of the tetragram. He drew the line in the dust of the floor with his finger. After counting the second row, comprised of tiny flowers, two remained, meaning a solid line for the next segment of the tetragram. The third row, of miniscule circles, added up to ninety-seven, leaving one, which in their improvised system meant another solid line. The last row of little squares yielded five at the end, for a line broken in thirds. The tetragram he had drawn in the dust was a line of three parts over a solid line, then a second solid line, over a final line of two parts. In the Tao te Ching chart the tetragram translated to fifty-six. He smiled sadly. The verse had been inscribed on the door of the secret temple he had frequented in Beijing during the years when the government had kept temples closed. He recited it out loud, whispering it the way a warrior monk in the cell might have whispered his rosary.

Those who know do not speak

Those who speak do not know

Block the passages

Close the door

Blunt the sharpness

Untie the tangles

Harmonize with the brightness

Identify with the way of the world

Shan contemplated the aged bow a long time after he finished. Then, slowly, with a tremble in his hands, he unrolled the ancient bowstring and fitted it to the bow. Why weren't bows used in all meditation? he wondered. So perfectly flexible, so perfectly taut, so perfectly focused. He remembered a blizzard day in his prison when a lama had issued all the prisoners imaginary bows and had them shoot imaginary arrows for hours, until no one could tell if they were drawing the bow or the bow was drawing them. He drew the bow back and held it, reciting the Tao chapter again and again. He held it until it hurt, until he knew what he had to do, and longer, until the danger of the thing he had to do was out of his mind and the bow was drawing him. Then he closed his eyes and in his mind took aim at a paper bird.

Chapter Nine

The truck bound for central Tibet departed when dawn was but a hint of grey on the horizon. One of the purbas sat on the hood with a small flashlight to avoid the telltale glare of headlights. Shan watched the truck from the rocks above as it coasted down the long slope, slowly climbed the next ridge, and disappeared into the vastness of the changtang, then slung his bag over his shoulder and starting walking.

He could tell from its birthing that the day was going to be clear and crisp, and he walked with vigor, his feet watching the path while his eyes watched the stars as they twinkled out. The air seemed to murmur, though he felt no wind. A nighthawk called. Something started in the rocks in front of him, fleeing with a clammer of small hooves.

In his mind he heard the Tao verse, as crisp as the call of the bird. Those who know do not speak. Those who speak do not know. Auntie Lau knew but she could no longer speak. Perhaps the dead American had known something, something about a broader conspiracy that was reaching into Yoktian. The dead boys could not speak, but sadly, he suspected they had known nothing at all about why they had died. The purbas and Maos were not shy of speaking, but their words were too often clouded with bitterness and hate.

As he walked with the sun rising over his right shoulder, he consulted the mental map he had made of the route Jakli had driven through the mountains. It was frustratingly short. He had slept too long in the truck the day before. Where his map ended, he would just keep moving north, toward the haze of the desert.

He walked two hours to the main road, and it was another hour more before the first vehicle approached. He jumped behind a rock and watched as a minibus, its sides badly dented and scarred as though it had barely escaped an avalanche, passed. In its windows he saw sheep standing on the passenger seats. Half an hour later he was walking on a steep curve around a high rock wall when the sound of another motor echoed down the road. He wedged into a split in the wall and watched a small car, its engine sputtering and belching greasy smoke, roll past. He eased out of the opening as it disappeared and found himself in the path of a truck whose approach had been masked by the car. As it pulled to a stop he recognized the odd-looking vehicle.

He sighed, then sat on a rock and put his bag on his lap. Jakli turned off the engine, climbed out, and sat beside him without speaking. The wind began to blow. A few small cotton-bright clouds scudded across the peaks.

"Sometimes on special days like this," she said after a few moments, "when it's so clear and deep, like a lake in the sky, you hear things. Groans and rumbles, the sounds of the earth. When I was young my Tibetan grandfather said it was the sounds of the mountains growing."

They watched the clouds.

"I said if they would just grow high enough, maybe everyone would just leave us alone."

A small grey bird landed and looked at them. "Why won't they leave us alone?" Jakli asked the bird in a voice that suddenly seemed to have the fatigue of an aged woman. She offered Shan her water bottle. He drank and handed it back, watching the bird as it watched them.

"This road," she said, with a vague gesture around the curve, "it goes north, out of Tibet. Not to Nepal, just back to Xinjiang."

Shan nodded. "I have eight days to get to Nepal. I am going back to Xinjiang first," he said softly, not wanting to frighten the bird.

"You have two days," Jakli corrected him. "After that no truck could get you there in time."

"I'm not going far, just to Yoktian. To the office of Prosecutor Xu."

Jakli considered his news a long time, then sighed. "If you confess to the killing of Sui," she said matter-of-factly, "just to call off the knobs, then I will stand up in the town square and say you're lying. I'll say that I did it."

He offered a small grateful smile. "I would give up much to keep the knobs away," he said. "But I will not give up the truth." Shan had simply realized that of those who knew but would not speak, the Prosecutor and her files perhaps knew most of all. "If Xu had discovered that Lau was a Tibetan nun," he said, "it would explain much. Why she has reacted so severely, made so many arrests. It would mean a campaign not against her traditional targets, but against Tibetans. And it would mean Kaju, the new teacher, must be one of the agents working secretly."

"But even so, what could you do?"

"Find proof about Kaju and expose him. Then even if we can't find them the children will stay away from him. He'll have to leave."

They watched the clouds. The sun emerged and lit the nearest of the snow-capped peaks so brilliantly it hurt the eyes.

At last Jakli sighed. "Where you go," she said, pushing her windblown hair from her face, "I will take you. We will find a way for you to leave in two days."

"No. You have a job, making hats. If you can make it to the factory, it's the safest place for you."

"It's a town job. I don't like it. They didn't ask me if I wanted to work in the city. I served my time behind the wire. They can't imprison me in a town too." She stretched, pushing her hands toward the sky. "Besides, I am going to my factory for a while, if the patrols don't block us. Check in, make some hats, just for fun." She pulled the bag from her lap and rose.

"It's too dangerous for you," Shan said, realizing that he had heard Akzu use the same words with Jakli. "I don't want you involved anymore. Please. You have a new life planned."

Jakli seemed to find the words amusing. "I could say the same about you," she said with a twinkle in her eye and stepped to the truck.

He followed her reluctantly and climbed in the passenger door. "If I write a letter," he said as the truck pulled away, "could you get it delivered to Lokesh? I left my blankets stuffed with sacks to fool the purbas. He was asleep under his already."

"Sure," Jakli said agreeably. "Just write and give it to me."

Shan retrieved his pad and opened it to a blank page. "He has no address," he added. "The purbas will know where he is."

"Actually, they don't. But I know the address. Kerriya Shankou," she said.

"Kerriya Shankou?"

Jakli waved her hand toward the rugged windswept landscape. "This pass. Entrance to Xinjiang. Postal code is the back seat."

Shan turned in confusion. The back seat was covered with a tarpaulin. He raised one corner. Lokesh was underneath, sleeping.

"He said he hoped you wouldn't be disappointed in him, that he was sorry to play a trick on you with his blankets. Looks like you all played a trick on the purbas."

"What do you mean?" Shan asked, looking at his old friend with a frustrated grin.

"They left in the dark, thinking all of you were under the blankets as they had instructed. But when I rose after dawn I heard someone outside, shutting the heavy door at the top of the rock. There's a flat rock there called the sentinel stone, between the lion's ears. I found Gendun on it. An hour later Bajys walked in. Said he jumped out of the truck because he discovered Gendun was missing."

"But Lokesh should stay with Gendun," Shan said.

"He said he has to go to the school in Yoktian. He said he would walk all the way if he had to." Jakli kept her eyes on the road but Shan saw her smile. "Said he didn't want you involved anymore, that he felt better knowing you were safe and going to your new life."

"Why the school?"

Jakli shrugged. "Because of Lau. Because of my friend the Tibetan nun." She mouthed the last words slowly, as if getting used to their sound.

***

The Ministry of Justice office in Yoktian had been built to palatial dimensions. Indeed, Shan realized as he studied the two-story structure's tiled roof and balconies from a bench in the town square, it probably had been built as a palace, though early in the last century. He remembered the crescent moon flag he had seen in Osman's inn. Yoktian had been a regional capital in the Republic of Eastern Turkistan.

As he sat and waited he watched a team of municipal workers progress along the stucco wall that surrounded the Ministry building. The three men in blue coveralls were attacking a series of posters that appeared to have been recently glued to the large bulletin boards that hung on the face of the wall. Not a series of posters, he saw, but at least twenty of the same poster. It held the image of a red-haired woman with light skin and large round eyes. Along one side of the poster was a line of Chinese ideograms, along the other a matching line in the Turkic alphabet. Niya Guzali, the poster said. Then, below that, Niya is our Mother.

The crew was stripping the posters away. Where the poster hung tight, they unrolled and pasted another poster over it. One Heart, Many Bodies, it said in bold Chinese ideograms, with no Turkic counterpart, then Achieve Success by Building Socialism with Chinese Characteristics. One of the men, as he finished pasting a poster to the wall, looked nervously about, as if he feared something or someone in the crowd that milled about the square. Shan surveyed the square. With a chill his eyes settled on two grey uniforms, knobs holding automatic weapons standing on the far side of the square, watching the work crew. Or perhaps protecting the work crew.

Nowhere else had they seen knobs. No arrests were being made. There had been no roadblocks to finesse. No camps were being raided for undesirables. The seemingly inevitable reaction to Sui's murder had not come. Surely the body had been found. Scavengers would quickly draw attention to it. Sui had been going to see Prosecutor Xu. She would have been the first to miss him, the likely one to find the body. But she had not raised the alarm.

Someone else settled onto the bench, facing the opposite direction, and placed a plastic bag between them. "Shoes," the figure said in a loud whisper. Shan looked at him uncertainly. He wore a purple dopa, set back on his thick black hair, and two gold teeth gleamed from his mouth. "My name is Mao," the man said as though to explain. "It's clear," he added hurriedly. Jakli had promised to confirm whether the prosecutor's car was parked anywhere near the Ministry building.

Jakli had first driven to the edge of the town, parking outside a complex of windblown buildings made of corrugated metal. She had run inside, under a frayed banner that proclaimed Hats for the Proletariat, Hats for the World, then emerged a few minutes later with a white shirt and grey pants. He had quickly changed in the truck, but when she had arrived at the Ministry building she noticed his tattered shoes and complained that they would betray him. Depositing him on the bench, she had driven away. Now, twenty minutes later, new shoes had appeared. Shan eased his old shoes off, slipped on the black shoes from the bag and then, without looking back, walked across the street. He carried a thick envelope, the kind a case file might be carried in. Jakli had bought the envelope at the post office and stuffed it with a newspaper.

He walked into a large two-story entry hall, with a high vaulted ceiling pockmarked where pieces of plaster had fallen away. A graceful wooden stairway curled up one side of the hall toward a set of double doors crowned by an ornate plaster archway. On either side of the entry hall the lower walls were covered with painted murals of beaming proletarians. The paint was cracked and peeling, leaving many of the figures without faces, some without heads, but all their fists were intact, raised in salute to the red flag of the People's Republic. A brown beetle was crawling across the nearest of the murals.

The floor of the room had been spared revolutionary fervor. It was an intricate mosaic installed many years earlier, with scenes of horses and mountains and bowmen that, though cracked in places, was still beautiful. A desk sat at the base of the stairway, and from behind the desk a pair of legs protruded. A bald, middle-aged man lay on the floor, snoring, his head resting on a folded jacket. As Shan had expected, government decrees seeking to break the tradition of after-lunch napping would mean little so far from Beijing. It was the slowest part of the working day.

He moved up the stairs at a deliberate, businesslike pace and explored the empty corridor before entering the arched doors. Two lavatories. A janitor's closet. Two small meeting rooms, both empty. A door to a back stairway.

Pushing open the door under the arch, Shan entered a large square central chamber containing four desks for clerical workers, two on either side of a central aisle that led to an ornate wooden door. There were two smaller doors on either side of the square. Only one worker could be seen, a thin young woman sitting at one of the desks closest to the ornate door, looking at her reflection in a hand mirror as she held a tube of lipstick near her mouth. He quickly saw what he was looking for, a small sign by the first door on the left. Records.

He squared his feet between the first two desks and stood, arms akimbo, waiting for the woman to turn. She saw him first in the mirror and spun about, her face flushed. She trotted to his side and greeted him with a quick, deferential bow of her head. She was Han, with her hair in an elaborate braid down her back, and she wore a red blouse that appeared to be silk, over which a gold necklace hung. Three of her fingers were adorned with gold rings. Expensive ornaments for a government office worker.

"Someone," he said, trying to muster the smug, impatient voice of Beijing officialdom, "was supposed to be here to help. Is that you?" Gendun had told him that no one was ever totally rid of prior incarnations, that vestiges of them lurked invisibly in the background of the current one. It disturbed Shan that the voice came so readily, that the old incarnation seemed so near now. The lower life form from which he had evolved.

The woman looked at one of the side doors, where others, Shan suspected, lay napping. "The prosecutor is out," she said meekly.

"Meaning what? That inspectors from Beijing must just wait at her convenience?"

The woman's eyes widened at the mention of Beijing. "No– no! Of course not, comrade. I am sorry. I am just the prosecutor's secretary. I'm sure she would want someone to– but I'm not supposed to leave the office unattended."

Shan tapped the envelope in his hand impatiently. "I have no time to wait. Bring my tea to the records room."

The woman winced, then bowed her head and scurried toward a bench at one of the rear corners of the room where two large thermos jugs sat.

Shan decided he could risk no more than a quarter hour. He spent the first few minutes of them studying the system used for organizing the cabinets that lined three of the room's walls. A cabinet of papers with a label "Reports to Central," arranged chronologically, held what appeared to be monthly reports to Urumqi and Beijing, dating back several years. Most of the remaining file drawers were devoted to two other categories: "Citizen Reviews" and "Proceedings."

No file for Khitai. No file for Bajys, or Alta or Suwan. No file for Kaju Drogme. For Lau there was a half-inch-thick folder in the Citizen Reviews, the kind of background file that would be compiled for anyone in political office, even one as low as the Agricultural Council. He scanned it quickly, starting with the back, the earliest material. Most of it consisted of a standard form completed on the basis of interviews with Lau and a dozen acquaintances, signed by a Public Security case handler with a copy to Prosecutor Xu. He wrote the name of the case handler in the notepad from his pocket, then read the details. She had described herself as orphaned during what the handler called the "period of violent anarchy preceding assimilation," which Shan took to mean the arrival of the Chinese army, and had been assigned to an agricultural collective in the north, in the Ili Kazakh Prefecture. Her birth records had been lost in the fires that swept public buildings in 1963, during the "Period of Adjustment." Shan paused at the term. He had heard many labels of the bloodbath years of the Cultural Revolution, when he had lost his father and uncles, but this was a new one. Period of Adjustment. An image flashed through his mind of violent clockmakers sweeping the countryside, replacing gears in the back of people's skulls.

At the bottom of Lau's form was a list of questions, with boxes to be checked for yes or no. Did the subject serve a period of patriotic service in the People's Liberation Army? No. Does the subject regularly read publications of the Communist Party to stay informed of the progress of socialist thought? Yes. Has the subject been observed in practices of the religious minorities? No. Does the subject have relatives living outside the People's Republic? No. Identify the cheng fen, the class background, of the subject. Not verifiable, although no reason to refute subject's statement that her family worked as farm laborers, it said. Farm laborers were the most revered of class categories. Lau had understood her audience. There was a brief memo near the top of the file, dated only three months before. It was written by Prosecutor Xu to Lieutenant Sui of the Public Security Office:

I attach no importance to the absence of comprehensive registration files for Comrade Lau. Comrade Lau like many of us merely suffers from the disarray in government administration that plagued Xinjiang until recent years. Her records for the past decade are complete and have been verified. Where records do not exist, our long practice has been to conduct ad hoc verification of political reliability, which was done in her case. Additional verification will be conducted pursuant to the procedures of this office. There is no basis for the suggestion that she be reclassified as a cultural agitator.

Shan read the memo twice. The words were plain enough, but what was important was what was not written. What the memo meant was that Sui had questioned Lau's reliability, not long after Lau had learned she was being dismissed from her Agricultural Council post. Someone had sent information against Lau to Public Security, information that might suggest she should be politically reexamined, possibly be reclassified as an undesirable, not a criminal but sufficiently suspect to be barred from a position of trust. And Xu had decided to intervene, to defend Lau. The prosecutor seemed to have no suspicions about Lau. He read the memo once more. Sui was suggesting that Lau should be confronted politically, and Xu was saying no, as if perhaps she had some other purpose for the hidden nun, some other goal that Sui was interfering with. There were no records beyond the ten years during which she had lived in Yoktian County. The murdered boys had been approximately ten years old. Could Lau's entire existence in Yoktian have been planned as a cover for raising the orphans? Or at least certain orphans? The memo had been copied to someone named Bao Kangmei. He had heard the name before. The warehouse at Glory Camp had been closed by order of Major Bao, who must be Sui's superior officer. He read the last last two sentences once more. They read like a reproach, as if Xu was chastizing the knob officer.