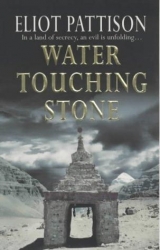

Текст книги "Water Touching Stone"

Автор книги: Eliot Pattison

Жанр:

Полицейские детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 18 (всего у книги 38 страниц)

The last entry in the file was a copy of another form, captioned "Report on Missing Person," signed by Prosecutor Xu Li, and showing that a facsimile of it had been sent to the same Bao Kangmei. Shan quickly scanned the form. The first report of Lau's absence had come from the school, then soon thereafter her horse had been found wandering along the river trail, and her jacket had been found in the river. Only the last paragraph had new information. Lau's identity papers had been turned in by a citizen to Lieutenant Sui, who personally verified that they had been found in the mud on the river bank near town. Sui had questioned Lau's political reliability, then had become involved in the investigation of Lau's disappearance.

He paused, then searched again for a file on Kaju. Nothing. He pulled the folder on Wangtu. Ten pages long, filled with routine entries. He dug deeper into the Citizen files. There was a file for Akzu, thicker than that for Lau. An ink stamp had been used on the cover. Cultural Agitator, it said in red ink. He scanned the file. It told the story of a peasant landowner who, like thousands of others, had been stripped of his property, then gradually rehabilitated. A memo dated six months earlier reported that Akzu had been singled out in a criticism session for failing to produce his clan's quota of wool. An agricultural expert had even testified that Akzu's stubborn adherence to outdated production techniques deprived society of valuable meat and wool. The most recent entry, dated a month earlier, was a memorandum from Brigade headquarters in Urumqi listing over fifty names of Kazakhs slated to go to a special year-long political education program upon implementation of the Poverty Reduction Scheme. Shan found Akzu's name halfway down the list.

He returned the file and stood sipping the tea that the nervous secretary had delivered to him. He had hoped for more, but what? A file on an anonymous American executed at Glory Camp? He opened the drawer on Citizen Reviews and found, to his surprise, one marked simply Mei guo ren. Americans. Inside were half a dozen memos from the prosecutor, all of them short, formal approvals for travel plans for American tourist groups. No, he saw, one was not a tourist group but a scientific delegation. Two years earlier a group of American archaeologists and anthropologists had come to the region under the wing of the Museum of Antiquities in Urumqi. There was a list of names and credentials attached to the memo, as well as a handful of photographs. Nothing that could be linked to the young blond American he had seen at Glory Camp. Shan recognized one name. Deacon. But it was a woman, Abigail Deacon, from Oklahoma, author of a book on ancient textiles. The files on the Americans ended with a date one year earlier. Stapled to the front cover was a stern note from the Public Security Bureau ordering that all reports on Americans henceforth be forwarded, without retention of copies, to Bao Kangmei.

He pulled another file, under Proceedings, for Jakli. There was a strip of yellow tape affixed to the edge of the file so it could be flagged easily when searching the drawer. There were other strips of yellow tape, not many. He quickly checked several. One was for a man who had been sentenced to life imprisonment for assaulting a birth inspector and who had escaped the year before. Another was for a man convicted and sentenced to ten years' lao gai for conducting a Lui Si remembrance ceremony. Lui Si, Six Four, was a reference to the 1989 disturbance in Tiananmen Square which occured on June 4. The yellow tape meant criminals with particularly dangerous politics.

He looked back at Jakli's file. It held copies of school files reporting classroom disciplinary infractions. A long report had been written by a political officer indicating that she had been a model student and targeted for communist youth camp. But then at age twelve that had changed. At age twelve, the officer wrote, she had come under the influence of reactionary culturalists. Meaning Kazakh sheepherders. When Jakli was twelve, Shan recalled, the army had shot her horse. The story ended two years earlier. No copy of Lau's letter to the prosecutor. He looked at the label again. Part One of Two, someone had scrawled on the file cover. But part two was not in the drawer. He looked on the table where a few files awaited refiling, then the Citizen Records in case it had been misfiled. Nothing. Someone else was interested in Jakli's current file.

Quickly he searched for one more file in the Citizen Reviews. Marco Myagov. Nothing. Then at the end of a drawer he saw a red-marked file, just labeled Eluosi. Six pages dealt with others, a form for each man and woman mentioned, rejecting requests for external passports. The remainder of the half-inch file was on Marco. Several applications for internal travel and work permits. He read the first one, dated nearly sixteen years earlier. Marco had applied for his young son and himself to travel north to Yining, to see an uncle who was dying. A large red stamp had been affixed to the front. Denied. Another, six months later, to attend the funeral. Denied. And another, to investigate a special school for his son. Denied. Request for a work permit. Denied. A dozen more requests, for a variety of reasons, all denied. The last was dated over ten years before. After that the material was all reports from Public Security suggesting his political unreliability, even suggesting smuggling activity. But nowhere was there mention of Marco being sentenced, not even to a rice camp, or any suggestion of hard evidence against the man. Shan moved to the most recent entry, a memo from Lieutenant Sui, copied to Prosecutor Xu. Interviews suggested Marco had organized one of the caravans that were still used to supply the high mountain villages at the top of the Kunlun and beyond, in Aksai Chin. Aksai Chin. Shan stared at the words. It was the disputed border zone, a barren, windswept territory claimed by both India and China, although controlled by the Chinese military. But Marco's caravan had gone out with eight riders, an informer reported, and returned with only four riders.

Shan quickly finished his notes and opened the door. The nervous secretary was at the nearest desk now, working at a computer console. A young man with the look of a soldier, though dressed in a business suit, sat at another desk reading a magazine. A bald man stood by the wall with a cup of tea, the man Shan had seen sleeping in the lobby. Shan hesitated, then pulled his notepad out and wrote on a clean sheet the name of Kaju Drogme. He stepped to the console and bent over the shoulder of the secretary, showing her the name. "I need to know who this man works for," he said.

The woman's face flushed, and her eyes flickered toward the man at the adjacent desk. "From the Brigade," she said in a self-conscious whisper. "Urumqi, I think. But here, it is Ko he reports to. Ko Yonghong." She looked up with a new air of self-importance. "Everyone knows Ko. He gives me rides in his new red car, one without a top. You know, like on American television."

Suddenly the arched outer doors burst open and Prosecutor Xu appeared, framed in the doorway. Shan bent lower, trying to hide his face behind the computer monitor. "Loshi," Xu called out as she stepped toward the secretary. "I need-" she stopped in midsentence. She had seen Shan.

He slowly straightened. She stared at him coldly, then looked at the young man at the desk, who had dropped his magazine and stood, suddenly alert, watching Shan with a predator's eyes. Shan realized he had seen the man before, driving the prosecutor's car at the motor pool.

"Thank you, Miss Loshi," Shan said. He returned the stare of the man he took to be the prosecutor's enforcer without blinking, then waited as Xu stepped toward the heavy wooden door at the rear and held it open. He turned and silently marched into the prosecutor's office. Xu stood aside to let him enter, stepped to Loshi's desk, and asked a question Shan could not hear. Loshi raised a sheet of paper to her chin, like a shield, as she nervously responded, then Xu returned to her office, closing the door behind her.

The room had been built as a sleeping chamber. Prosecutor Xu's desk was on a short platform that rose out of the rear center of the mosaic floor, extending in a broad rectangle to the back wood-paneled wall, just the size for a large bed. Several chairs were arranged in a semicircle on the platform in front of the desk. Not exactly a desk, Shan saw, but a heavy table of dark wood, its edges carved with the shapes of birds and flowers, similar to the designs on the floor. Another artifact of the building's past, the kind of remnant that would have been thrown onto a bonfire years earlier if it had been found in the eastern cities. Shan settled into the center chair.

Xu sat at her table and folded her hands in front of her. "Not even an inspector from Beijing has the right to use my office without my permission," she growled.

"Your office, Comrade Prosecutor, belongs to the Ministry of Justice," Shan said, surprised again at how easily the words rolled off his tongue. Not surprised, he thought after a moment, but frightened, that the old Shan, the one-time Inspector General of the Ministry of Economy, lurked so close. He clenched his jaw and tapped the envelope. "Ministry representatives are always entitled to access if they are looking for corruption, say, or abuse of office."

The words had the desired effect, silencing Xu for a moment. Shan had little hope of defusing her anger, but he might deflect it, might at least stall it on the chance, however improbable, that an escape presented itself. And if he could not escape, he might use her arrogance to at least get her to admit what she knew about the killings.

Xu's lip curled up as if she was about to snarl, but she looked into her hands, not at Shan. "I have nothing to hide. I have nothing to fear from-" Her words were cut off as the door was flung open and a thick bull of a man burst into her office.

"Call them off!" the man shouted at Xu. "Order your damned whelps off or I'll call Beijing! You are endangering my investigation!" His heavy cheeks were flushed with color. Drops of saliva shot from his mouth as he shouted.

Shan didn't need to see the grey uniform to know what the man was. The Public Security Bureau had arrived, and if he had had a slim chance of escape a moment earlier, he had none now. He rose slowly, fighting the knot that was tying itself in his abdomen, and silently pulled a chair from the side of the desk and sat again, facing the knob officer, as if he were with Xu. The prosecutor did not seem to notice. The action took Shan out of the line of fire between the two and gave him a clear view of the furious stranger.

His hair was close-cropped and speckled with grey, like Shan's. His face had the broad, flat features of the southeastern coast, a region known for its fishermen and pirates and the difficulty of distinguishing between the two. As his barrel chest heaved up and down, Shan saw a bulge on the left side of his uniform, below the armpit. A pistol, strapped under his tunic.

"You will have to be more specific, Major Bao," Xu said icily.

Major Bao. It was the knob officer who had demanded all reports on Americans be sent to him, the one mentioned at Glory Camp. Lieutenant Sui's commanding officer. Shan remembered what Fat Mao had said. The two people in the county to stay away from were Prosecutor Xu and Major Bao.

"Specific, hell!"

"Major, you're overwrought." Xu seemed accustomed to his fury. "Sit down."

Shan studied the two in confusion. They should have started their feeding frenzy by now. They should have begun the process of dissecting and digesting Shan. But Xu and Bao appeared to be little interested in cooperation. Lieutenant Sui, who must have reported to Bao, had been with Xu at the motor pool. Bao Kangmei had also been the name copied on Xu's memo about Lau. Shan looked at the knob again. His hands were like cabbages, his eyes like dirty ice. Bao Kangmei. Resist America Bao. It had been a popular name during the struggle with the Americans in Korea.

Bao made a sound like a growl and dropped into the center chair just vacated by Shan. "Your damned investigators are spooking everyone," he said in an icy tone. "Everyone's running to cover. The caravans will stop moving. If you ruin my operation, I'll ruin you."

Shan studied the knob. Bao didn't want to stop the caravans, he wanted them to keep moving. Shan remembered the black market goods at Glory Camp, in the shed guarded by the knob guard. In the shed with the dead American. Was that all it was? Was Bao just a black market businessman? Perhaps the American had simply been an unlucky merchant, in Xinjiang to buy carpets on the black market, perhaps even to trade for electronic goods.

Xu sighed as if she were sympathetic to Bao. But her face showed no warmth. "My team has never been closer to a breakthrough. The Poverty Scheme is what we have waited for all these years. I will not call them off a real case so you can chase phantoms."

"Not phantoms, Comrade Prosecutor. Enemies of the state. Enemies of Beijing."

"It's your crutch, isn't it, Major?" Shan looked up in surprise at Xu's words. Never had he heard anyone speak in such a tone to a knob. "You're the only one who speaks of Beijing so often. But I am the one who catches criminals. Beijing knows that."

Bao glared at her.

Xu's face seemed to soften, now that she had scored against him. "Surely a few minor inquiries in the mountains can't upset an important Public Security operation, Comrade Major."

But Bao did not seem to have heard. His oxlike head was turning to the side, looking onto a huge table, bigger even than that used as Xu's desk, which was pushed against the wall. It seemed conspicuously oversized, as though ready at any time to receive a banquet or a body, at Xu's convenience.

A single cardboard box sat in the center of the table. On it, written with a broad black marker, was a name. Lau.

Bao exchanged a silent, meaningful look with Xu, then rose and stepped to the table. Xu stared after him with an icy expression. By the time she had joined him Bao had dumped the contents of the box on the table. Shan stood to see better, then glanced at the door. He might make it if he walked quietly away, without attracting those in the outer office. But he turned back to look at what Xu had collected from Lau. Three books. A short, narrow knife, like a dagger. A wooden box, the size of a shoe box, though half as high. Several notebooks. A small jade statue of a horse. A simple white metal box, dented from long use, inlaid with a row of pink coral squares on its top– a pen case, of a type often seen in Tibetan instruction halls.

Oddly, the discovery seemed to have subdued Bao. He stared at the evidence, then at Xu. "You have been sharing the results of your investigation with my office, no doubt."

"We have no official investigation results yet comrade. Just a missing persons review, after all. These are simply personal effects. In case we ever identify her family. Things from her room in the teacher's dormitory. Space is in short supply. Her room was cleared out for another teacher."

"But still," Bao said in a taunting tone, "here they are, on your evidence table."

Shan quietly inched his way toward the table. He stood back, out of Bao's reach, but close enough to see the objects clearly. The books were poetry. The top one Shan readily recognized, the works of Su Tung-po, a broken Sung dynasty official who had written beautiful poems about living in exile.

"Even in death you are too kind to her," Bao said as he picked up the knife and waved it in the air, as if it proved a point.

"A letter opener," Xu shot back, not bothering to hide her impatience.

As the major clamped his huge hand over the wooden box, Shan saw that it was of rosewood, a superbly crafted container carved with delicate flowers along its rim. Bao raised the box and shook it. Something rattled inside. He turned the box over, looking for a latch.

"A puzzle box," Xu said tersely. "Ching dynasty."

Shan saw that she was right and realized with pleasure that it was a very old piece, one of the wooden puzzle boxes that had been popular in China two centuries earlier. No two would be alike, and each would be opened by pressing a certain point or sliding a series of pieces out in the right order. He realized with surprise that Xu might have been saving it, as Shan would have, to discover the right combination of pressure and pushing which would unlock its secrets.

"You really don't understand, do you?" Bao observed in a gloating voice. He looked at the prosecutor with a strange pleasure in his eyes, then laid the box on the table and with an abrupt hammerlike movement of his fist smashed it open.

He ignored Xu's glare as he picked through the shards of wood. There were two pieces of metal inside, one a two-inch trapezoid of bronze, engraved with a figure of a flying bird, a hole at each end. The other was a brilliant gold coin.

Bao extracted the gold piece from the splinters and extended it like a trophy. It was a Panda, the one-ounce gold coin minted by Beijing for the international collector's market. The Major gave Xu a victorious glance and, still extending the coin in front of his chest, returned to his chair. As Xu turned to follow Shan quickly pocketed the bronze medallion.

Bao let the prosecutor wait and watch as he set the coin on the desk in front of him, then slowly, clearly relishing Xu's discomfort, he produced a pack of cigarettes and lit one. "Maybe," Bao suggested as he exhaled a sharp stream of smoke, "you don't always catch the criminals, Comrade Prosecutor."

"Lau labored for many years," Xu said in a smoldering tone. "A model worker. There is no crime in saving wages."

Shan stood by the table, looking at the coin in front of Bao. It was worth more than some herders made in a year.

"Your model worker had secrets. Good citizens don't keep secrets. A true believer in the socialist imperative keeps no secrets." A row of yellowed teeth showed as he offered a narrow smile. "There are those in Yoktian who want to unravel the fabric of society. It all starts with a few loose threads."

"What do you imply?" Xu shot back. "She was one of those holding it together. We needed her."

As Bao shook his head he exhaled, creating a cloud of smoke about him. Then his gaze settled on something under a piece of paper on Xu's desk. He leaned forward and snatched it up. Shan instantly recognized it, a wedge-shaped tablet like that in Suwan's belongings. Not the same, for this one had a crosshatch design across the top edge, but bearing the same Sanskrit-type writing. Bao slid the top out, then slammed it shut and stood. "Where did you did you find this?" he demanded.

"Lau's things." The prosecutor lit a cigarette, inhaled deeply, then shot a stream of smoke toward Bao. Like a duel of dragons, Shan thought. He found himself stepping closer, looking at the wooden tablet.

Bao's eyes widened for a moment, and he looked back at the items he had scattered across the table. He said something to himself in a low venomous tone, so low Shan was not sure he had heard correctly. "Bitch," it sounded like, "the traitorous bitch." Then he met Xu's puzzled gaze. "You haven't called anyone about this?" Bao barked. "The Ministry? The Antiquities Institute?"

Xu shot an uncertain glance toward Shan, then slowly shook her head. "Just a toy of wood some children made."

Bao's eyes closed to two narrow slits. "Fine. Keep thinking that, comrade," he spat. "Treason all around and you only see toys." He spoke to the wooden wedge now. "Think of all the work that has been done, all the sacrifices we have made to establish the most glorious society on the planet. The government gives us everything. We owe it everything. To think that there could be those in this very county who seek to tear our state apart, it sickens me," the knob growled. "You're wrong about her, Comrade Prosecutor. She wasn't who she said. There is no lower life form than those subversives who seek to undermine the state. Insects. Maggots, all of them, especially Westerners who foment it. We will crush them. And I will also crush those who stand in our way." He stuffed the wooden tablet into the big flapped pocket at the bottom of his jacket.

Shan found himself standing at the desk. He quickly sat back in the chair near Xu.

Xu's face drew tight as she stared at the pocket where he had stuffed the tablet. "I thought we were speaking of caravans." Did she recognize the dangerous ground Bao was pushing her toward? Shan wondered. Or was she simply reacting to the wild gleam in his eyes?

Bao's hand moved to a breast pocket, from which he extracted a folded piece of rice paper. "You've never seen this, I suppose?" He unfolded it and extended it in his hands a moment, then turned it over. It was a strip sixteen inches long, a poem inscribed in a child's hand, in Mandarin on one side and Tibetan on the other. Master's gone to gather flowers, the first line said. Pollen on his funny robe.

"Discovered hidden in her quarters," Bao stated. "Fortunately Public Security was able to intercept it instead of another office," he added pointedly, then folded the paper and stuffed in back in his pocket.

"A child's imagination," Xu offered stiffly, though the writing seemed to shake her.

Shan stared at the floor, avoiding eye contact with either. The poem was written about the waterkeeper. Bao suspected there was a lama somewhere, an illegal lama, and that Lau had been connected to the lama.

"I was in Turfan too," Bao said, giving no sign of having heard the prosecutor. "I heard the speeches. Some have lost sight of their essential duties. If you neglect your essential duties, no matter how hard you work, you are a liability to the state." It was a familiar code Bao was using now, speaking in political slogans.

As the major finished, his gaze rested on Shan for the first time. "Do you know your essential duties, comrade?" Bao asked him with a narrow, lightless smile. "Do you recognize treason when you see it?"

"I remain ever mindful of what I owe the state," Shan said woodenly. He fought the almost overwhelming urge to bolt. Xu's enforcer was outside the door, then the man at the stairs, perhaps others who had returned from their rest. With luck, Shan might get past them. But Major Bao was not the type to travel without an escort. There would be more knobs outside.

Bao let the smoke drift out his mouth so that it curled around his cheeks. "Tell your prosecutor to do the same."

Shan clenched his jaw so tightly his teeth hurt.

"I am not his-" Xu began. Shan turned toward her with an empty expression, resigned to his fate. Xu locked eyes with him for a moment, then looked back at Bao, without continuing.

"I do not consider Prosecutor Xu a woman who forgets her duties," Shan offered.

Bao gave Shan another narrow smile and leaned toward him. "I thought I knew all of the trained hounds here. You're new?"

His incredible luck had failed. For a moment there had been hope that both would end the meeting with mistaken assumptions about him. But now there were only two ways to leave the room. With Xu or with Bao. He couldn't say he worked for the knobs, as Xu had assumed. He couldn't say he worked for Xu, for any disclaimer from her would mean immediate arrest by Bao. Shan's only hope was to give Xu something, perform for her now, make her curious enough that she might offer him cover.

Bao stared at him with sudden, intense interest.

"I am new," Shan said. "I am from Beijing."

"Who are you?" Bao pressed. "Your name."

"Someone who is wondering why you seem more concerned about smugglers than the murder of one of your officers."

Bao's eyes flared and his upper lip began to curl at one edge, exposing a large yellow tooth, like a fang. He stood and threw his cigarette, still lit, onto Xu's desk. "You don't know that."

"On the highway. Two days ago."

Bao did not take his eyes from Shan. "Accidents happen on the highway," he muttered.

"His name was Lieutenant Sui." Shan heard a sharp intake of breath from Xu, behind him. "Two bullets in the heart. Surely you have reported it. Beijing takes great interest in attacks on Public Security officers." Could it be possible that Xu didn't know about Sui?

Bao's face paled. His lip curled higher, toward his nose. It was not a sneer– more like the way some animals bare their teeth before tearing into the flesh of their prey. Without looking Shan sensed Xu's body tighten, but he did not take his eyes off Bao. The major reached Shan's side in two quick steps, then raised his open hand and slapped him, hard.

"No officer was killed," he snarled. Then, in his next breath, as only one trained in the peculiar logic used by political officers could do, he asked, "How do you know this? This is a Public Security matter." His furious question was directed at Shan but Bao's eyes came to rest on Xu. Then, as if his remark needed further punctuation, he raised his thick pawlike hand and slapped Shan again.

Shan tasted blood from the inside of his cheek. He would sit there and let Bao slap him all day but he would say no more. Shan had found a place inside, an oddly serene place, a little room he had constructed in prison and not visited since. Some prisoners had called him the Chinese Stone for never breaking from physical punishment. Some of the Tibetans had said it was because his soul had sufficiently evolved so that he was always prepared to leave his body. He had never thought they were right. He only knew that he had evolved sufficiently that, no matter what, even under the threat of death, he would not cower before men like Bao. It didn't mean much to the world if such men couldn't get what they wanted from physical torture, for they could usually obtain it through chemicals. It only meant something to Shan.

As he braced for another blow Shan reminded himself of the Tibetan prisoners who, after all the torture, the starvation, the freezing, even the amputations, thanked the Lord Buddha for allowing them the opportunity to test their faith.

Through a fog of pain Shan heard Xu push back her chair and step away from her desk. He had lost. She was going to join in Bao's fun, he thought numbly.

"This is Prosecutor Xu Li of Yoktian County," he heard her say in a loud, professional tone, the way she might speak before a tribunal. "In the name of the Ministry of Justice I am demanding that Major Bao immediately desist."

Bao had found a place within himself too. Not a place of serenity. Perhaps the opposite of serenity. As the Major looked toward Xu he made a sound like a snarl, a sound of disgust. Shan followed his gaze. He had to blink hard to focus on the prosecutor, blink several times before he fully understood what she was doing. Xu stood with a video camera. She was recording Bao's actions.

Bao picked up a tea mug and threw it, not at Xu, but at the wall beyond Xu, who kept filming as the mug shattered behind her. Then he grabbed the gold coin, spun about and marched out of the room, slamming the door behind him.

A brittle silence lingered in the office. A thin line of smoke rose from Bao's cigarette, still on Xu's desk. Xu approached her desk and stood looking at the door, then looked at Shan. She raised the smoldering cigarette with the paper it had landed on and dumped it into a mug at the side of her desk, then picked up the phone and asked Loshi to bring in two teas.

The prosecutor circled her desk twice, her arms folded over her chest, not speaking until the tea arrived.

"I could have you behind the wire at Glory Camp before nightfall," she said.

"I've been to camps," Shan said quietly, returning her stare over his steaming mug. "Good exercise, bad food."

"I thought you were working for Public Security when I met you. One of the new agents brought in for the project."

"The Poverty Eradication Scheme?"

Xu did not respond. "Let's say you're not Public Security. Let's say you're not Ministry of Justice, not here on a corruption investigation. Just theoretically. But you know that Sui was killed, a secret kept even from me." Xu had not challenged Shan's announcement about Sui. Bao's reaction, he realized, had been confirmation enough. And Shan had been wrong. Xu had not known about Sui's death, he was certain. But Bao had. The knobs knew one of their own was murdered, and they were doing nothing about it.

"Walk around one of the markets and listen for twenty minutes. You'll see how big a secret it is."

She still ignored him. "So let's say you were associating with bad elements. Say, independence-minded herdsmen. Maybe subversive hatmakers."

The words hit Shan harder than Bao's hand ever could. Xu had seen Shan at the garage with Jakli, maybe also checked at Glory Camp for the names of anyone on the rice truck known to the guards. He glanced across her desk, looking for the second half of Jakli's file, the active half.

"I don't wear hats," he said weakly.

"Then maybe you're with the smugglers. We'll have lots of time to decide."

"I'm not with anyone."

"But you are from Beijing. I can tell. Your accent maybe. Or your arrogance in getting around my office."

"As I said, I am an investigator. My name is Shan. And I am from Beijing."

"But not investigating for Beijing. Surely not an independent investigator? Please, comrade. This is not some American movie."

"I am retired."

Xu studied him over the top of her teacup. "And you say you've been in camp before? Maybe you were forcibly retired."

Shan raised his mug. "I salute your deductive powers."

"And what? You're investigating as a pastime?"

"I was asked by friends to look into something. Nothing that concerns you," he offered, though he didn't believe it.

"Except you wind up breaching security at Glory Camp, then rummaging through my files."