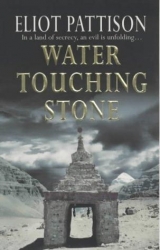

Текст книги "Water Touching Stone"

Автор книги: Eliot Pattison

Жанр:

Полицейские детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 36 (всего у книги 38 страниц)

"Circumstantial," she said.

"Ko must have been in a Brigade truck in Tibet with others that day, just like the next night when we saw them. It shouldn't be hard to find some of those who were with him. You could interrogate them. Get statements. It's one of your specialities, I hear."

She did not rise to his bait. "Bao found Lau's body," she said instead. Shan's head snapped up. "Or said he did. So we called, said an autopsy should be done. He said the Bureau already did one, confirming drowning was the cause. Body was cremated in Kotian."

"The body?"

"He had a body. But he didn't know my office uses the crematorium in Kotian too. We called, and the technician said the job had been delayed, that they were just about to start. I said we needed one last check of the woman's identity, and he called back five minutes later, all upset. Wasn't a woman at all. It was a young man, and he hadn't drowned, he had been shot twice in the chest. Mistakes happen I said, just put him away in the morgue. We'll be in touch."

"Lieutenant Sui." Shan spoke toward the graves, as if their occupants deserved to know.

The prosecutor nodded. "It's a strange sort of coverup. If Bao shot Sui he would have been more careful, there would have been no body. He's cleaning up someone else's mess. Someone he won't prosecute."

"Ko. Ko shot Sui. I met a witness. Bao found out, and Ko gave him his car to quiet him. Now they're business partners, thanks to Rongqi. Bao is protecting Ko, at least for now."

"Ridiculous. Bao and Ko, they're totally different. Never been friends. I've known them ever since they arrived in Yoktian."

"I saw a banner for the Poverty Eradication Scheme," Shan said. "Unify for Economic Success. I think Rongqi created a bond between them, a mutual interest."

"Like finding your boy lama?" Xu asked in a skeptical tone. "You're talking about the Brigade, one of the biggest companies in China, and the Public Security Bureau."

"No. Not the Bureau, just two renegade officers. Sui hid what he was doing from Bao. Sui killed Lau and got a lead on Ko in trying to find the boy. Ko killed him, because Sui was getting too close to the big prize. Then, later, when Bao discovered what had happened, he stepped into Sui's role. Unify to maximize the bounties. They can collect more if they work together. Rongqi increased the prize, too much to ignore for someone like Bao, stuck in Yoktian on a knob's salary. Creating a false record in the Lau investigation, that would be nothing for someone who kills boys for money," Shan sighed wearily. "Arrest them both. You'll be a hero."

Xu grimaced. "There's still no hard evidence."

"A body in the morgue is a good start. And there's a witness to Sui's murder, hiding in the mountains." Shan studied her. "You just mean there is no political explanation."

Xu was silent, looking out over the field of tombs. The wind blew sand in drifts along the rows of graves.

"Corruption is political," Shan suggested. "Bring down Rongqi, and you can get out of Xinjiang."

She made her grimace again. "I need books. I need ledgers. I need evidence. Offering economic incentives with private money, that's no crime."

"Offering a bounty to kill a boy is."

Xu shook her head. "One word from Rongqi to a boot squad and we can all wind up in lao gai. You don't possibly think I could touch the general."

Shan stared at her. Her eyes remained as hard as pebbles but she would not meet his gaze. "I think you can. I think you're just scared."

"Sure. Next he'll have a bounty on uncooperative prosecutors."

"No. You're not scared of Rongqi. I think there is only one thing that truly scares you." She looked at him. "I think you're scared of becoming me."

The sound that Xu made seemed to start as a laugh, but ended more as a whimper.

"It's possible to stand up to them," he continued. "But if you do, it's also possible to end like me." He spoke in a matter-of-fact tone, as if speaking of some strange lower life form, not of himself.

She stood and abruptly walked away, down a row of tombs. The wind picked up as the sun began to sink behind the mountains. It shifted and filled with the acrid smell of the ephedra bushes that grew along the desert fringe. It was cool, almost cold, a sign of a shift in seasons.

He followed, but not all the way to her, stopping six feet away to bend at a grave. He began clearing away the dead leaves that had gathered against its wall. One of the traditions lost to most modern Chinese was Chen Ming, the festival when one swept the graves of ancestors and placed a branch of willow over the door to ward off evil spirits. When the government outlawed graves, it had effectively outlawed the festival day. Once Shan had found his father trying to fasten a tiny willow twig to the frame of their door, and his father had made an awkward joke about it and walked away. But in the night the twig had appeared over the door.

"You are going to get a report of a crime in the next few hours," he said in a loud voice as he worked. "Bao arranged it. Someone will say another boy has been attacked, maybe even killed. In the mountains. The kind of call the prosecutor's office must respond to. You will need to go immediately, or in the morning, early."

Xu gave no sign of having heard. She wandered away. A few minutes later she appeared on the other side of the tomb where Shan worked. "You mean a trap?"

"A distraction, I think. Because tomorrow morning is when Bao and Ko plan to catch the last boy. The one with the Jade Basket. It's timed perfectly for the general's visit. The big prize at last, presented to him when he arrives."

"He's here," Xu reported. "Came this afternoon, staying at a special Brigade guesthouse. Has boot squad bodyguards."

Shan sighed. "Perfect. Arrest them all."

"Lunacy," she shot back. "You've lost all sense of the bond between the government and its citizens." The words came out forced and hollow.

Shan just stared at her.

"You've been in Tibet too long," she accused him.

"I read something on the bond between the government and its people," he replied. "It's called the Lotus Book."

The words had a strange effect on the prosecutor. Xu seemed to stop breathing for a moment. She looked out over the tombs. "It's not like that," she said after a long time, in a taut voice.

"When you're in prison," he said quietly, speaking toward the horizon, "you always wake up without making a sound. People learn to have nightmares with silent screams, because of what the guards do if there is noise." The woman looking at him now was not the prosecutor. It was someone he had never seen before. The stone in her face seemed to have shattered. "But one day I woke up to the sound of a beautiful bell. Not loud, but true and harmonious, resonating to my bones, a perfect sound. Later I asked a lama who rang the bell. The lama said there was no bell, but at dawn he had watched a single drop of water drop from the roof into my tin cup. He said it was just the way my soul needed it to sound."

"I don't understand," Xu whispered, toward the graves.

"It's only that it changes you, Tibet. It makes you see things, or hear things differently. It marks you, it burns things into your soul." He looked at her. "Or sometimes burns through your soul."

Xu turned to put the sunset wind in her face. "In that book," she started, as if trying to explain something.

"Know this," Shan interrupted, for he would not deceive her. "I read nothing about you in the book." But he remembered the strange look on her face when she had stared at the Kunlun, and how Tibetans worried her.

She seemed relieved for a moment and turned toward the stairs. But when she reached them she sat on the bench again. He worked on the grave a few more minutes, until it was clean, and still she just sat, staring over the weed-bound tombs.

Shan walked out of the graveyard and stepped past her. He was on the first stair when she spoke. "There're three hundred forty-seven graves here," she said, in her whisper again. "I counted them once."

He sat on the stairs. A large bird soared over the graveyard and roosted on a far tomb. An owl. Keeper of the dead.

"I was only sixteen," she blurted out, almost a sob. "We made a truck convoy from Shanghai, gathering more and more cadres as we went. They elected me officer. I never asked for it, but they said I could recite more of the Chairman's verses than the others in my unit. We traveled for weeks. We broke down fences to liberate livestock. We burned schools to liberate children. We burned libraries to liberate knowledge."

The Red Guard, Shan realized. She was talking about the Red Guard and the Cultural Revolution.

"When we got to Tibet they assigned me a district and a quota. Ten percent of all citizens were declared bad elements, and I had to identify my ten percent and submit them to struggle sessions, public criticism, violent criticism. Sometimes fatal criticism. Gompas had to be eliminated. The reactionaries had to be punished. Fourteen times our unit forced children to shoot their parents." She paused and surveyed the graves again as if she were thinking of counting once more. "We were only children ourselves. Sometimes they stripped lamas naked and made them dance in the town square."

"They?"

Xu was silent. She ran her hand over her lips. It trembled. "We," she said at last and pushed a knuckle into her mouth. She took the finger out after a moment and stared at it, as if not understanding what it had done. "I wanted to stop. I wanted to go home. I was tired of the brutality. I was worried about my family. But if you spoke about family you were criticized. Sign of a reactionary, sign of addiction to the tradition of oppression. All I could do was continue. We got awards. A model unit. I kept getting promoted. There was a gompa far in the hills, a big gompa past Shigatse. The Revolutionary Committee came with photographers from Lhasa to watch us do our job. We surrounded the gompa and sang songs of the Revolution. I gave the order to burn it. I thought the monks would come out, they had time to. But they didn't. Some of them stood in the doors and looked at us as they burned. But most just stayed inside, saying their mantras. For a long time we could hear them, louder than the roar of the flames. Afterwards we found the bodies in rows, because they had carefully sat in their sanctuary with their lamas facing them. Rows and rows, like a cemetery. We celebrated and sang our songs again. Three hundred forty-nine. The Chairman sent me a letter of commendation. It's how I got my first job in the Ministry. Because I had the letter from the Chairman. It just said I did a good job, that I was a model worker. It didn't say it was because I had killed three hundred forty-nine monks."

Shan had no words. A history teacher had once told him that the only problem with modern China was that people lived too long, that too many millions lived to old age, when they began to cultivate a conscience. For Xu the nightmares had come early, and her conscience had trapped her. It's not like that, she had said of the Lotus Book. Meaning, It was like that, but now I am a different person. She was as surely a prisoner as those she sent behind wire, self-exiled in the borderlands where she thought she might make a difference.

She seemed not to notice when he rose and climbed the stairs. He passed the car without looking at the bald man at the wheel and walked back to town, the wind throwing sand across the road, his soul so heavy he thought he might never hear a bell again.

Chapter Twenty-One

Sand blew down the streets of Yoktian, obscuring their broken curbs and other imperfections, blurring the cracks in the walls. It was as if the entire town had been airbrushed for a cleaner, more wholesome image. Perhaps on the general's orders. But Shan was not fooled. There were still holes in the street that would break your ankle and fissures in the walls where rats waited.

A cargo truck was at the rear of the restaurant when Shan arrived. Gendun and Lokesh were asleep in the front room under two tables that had been pushed together, as if the Maos expected an earthquake. Jowa sat beside them, lotus fashion, watching them. As the stout woman extended a mug of tea and a bowl of noodles toward him, the truck's engine started.

"Rice camp," she said in response to his look of query, and he bolted out the door, jumping into the cargo bay so quickly that he did not realize until he sat down that the tea was still in his hand.

Fat Mao, sitting in the shadows behind the cab, was not happy to see him. A quick trip, he said, to pick up the order for the next week's food delivery, although Shan knew better. They were going because of Red Stone clan, because the next afternoon the clan would be disbanded, because Akzu and Fat Mao had a plan they would not explain. But Shan did not care. He was going for the waterkeeper. There was nothing else to do except wait for the dawn, wait for the meeting at Stone Lake, for the final confrontation where the killers would come to collect their last prize, where Shan had to be before the knobs, to whisk the boy away if he and the herders guarding him eluded the Maos, who would be trying to intercept the boy on the roads leading to Stone Lake.

The adminstrative compound at Glory Camp was deserted. The gatehouse itself was empty and the gate locked. But Ox Mao climbed out of the driver's seat and quickly unlocked the padlock. They parked by the warehouse and a woman followed the big Kazakh out of the front seat– Swallow Mao, wearing a severe-looking business suit. The woman carried a large envelope and marched toward the administrative building with an air of authority.

Shan stood by the inner wire, studying the barracks with the holding cells, inside the prisoner compound. He had no plan, no idea, no confirmation even that the lama was in the barracks. Even if Swallow Mao could find his hut assignment the Maos could not risk entering the second wire, which was where the real security started. He bent to a small clump of dried asters that had managed to survive in the sandy soil at the base of the inner wire. Plucking one of the stems, Shan tied it to the wire at the closest point to the holding cells. Maybe, he thought sadly, he had come just to say goodbye. The old Tibetan would not last long once Bao, or Rongqi, discovered he was a lama. He looked back at the administrative building and slowly, reluctantly, turned his head toward the small shed where he had found Nikki, then the boilerhouse.

He started walking, without conscious effort, and found himself under the boilerhouse roof. From twenty feet away he could feel the heat of the furnace and he stood there, the image of the spirited blond youth by the boiler door burning through his mind. Not much older than his own son. He walked out the far side of the building and stopped at the edge of the cemetery. In the dim light of the cloud-covered moon the graves seemed endless. With small, uncertain steps he started toward the far end, where the freshest mounds of earth had been.

Then he saw the animal. A low shadowy hulk, it moved along the graves as though following a scent. Shan looked down for a spade, a stick, anything he might use as a weapon. The creature lingered at one of the freshly dug piles of earth. With a pang of fear Shan wondered what he would do if it began to dig for the dead. Scavengers preferred rotten meat. Feebly, he stepped forward. The beast paid him no attention. It pawed idly at the earth in long motions that gave the impression of a great and reckless power.

After a moment the animal leaned back and sat up on its rear haunches. As the moon appeared from behind a cloud Shan gave a half-choked cry. The animal was Marco Myagov.

He stood in silence for a long time before venturing a step forward. Marco tensed and seemed about to pounce on him, then eased back as he recognized Shan. Shan spoke no word of greeting but instead began to range among the graves himself, surveying the mounds, trying to remember how they had looked on his first visit. After a few minutes he stopped at a group of three fresh graves. "Here," he said. "This is where he would be."

Marco seemed to require great effort to rise. He wiped his hands, caked with soot and the dirt of the cemetery, and joined Shan.

"He is-" Shan struggled to find words. "He is with many good men." Despite their miserable deaths in a forgotten wasteland, many of those laid to rest before them were men who defied the dictators, who had been true to their beliefs.

Marco gave no sign he had heard Shan's words.

"I thought you were-" Shan offered tentatively. "I saw the flames, I thought you had died." What if this was not Marco, he thought with alarm, what if it was some frail shadow of Marco, some wraith left after he had lost his soul that night?

But then the man spoke, and Shan sighed with relief. "She burned," Marco said in a hoarse voice. "God's breath, how she burned."

"But why are you-"

"I have had talking to do with my Nikki."

"Then what?" Shan asked after a moment.

"I told you before. I get bastards. It's what I do."

The words somehow made Shan sad. "They need you. The Americans still have to get out. They're in great danger."

Marco looked at Shan, with an expression of confusion, as if he had not thought of it before.

"They'll kill you here. There're soldiers. You won't have a chance."

Marco did not reply. He selected the middle of the two graves and sat on the earth by it, then patted the soil beside him as though gesturing for Shan to join him. Shan knelt by the end of the mound.

"I would not fear to stay here with Nikki," the Eluosi said, almost brightly. "I have nothing left. I have no country. I have no family. I have no home."

"But what would Sophie do without you?"

Marco's eyes rested on a patch in the darkness, in the shadows of the knoll by the camp. He sighed heavily and pulled something out of his pocket. In the moonlight Shan recognized it. The Russian medal he had seen in Nikki's room. The medal from the Czar.

Marco scooped loose soil from the head of the grave and buried the medal, then spoke in Russian for a long time, looking first at the grave, then at the sky.

When he finished Marco shifted his gaze toward the compound. His eyes had a new, sharp glint, a warrior's eyes. Suddenly he rose and began jogging toward the boilerhouse.

By the time Shan caught up, he was at the open boiler, rapidly shoveling in coal. He motioned toward the loaded barrow at the front of the shed, and Shan pushed it toward him. Soon the boiler was packed with fuel, almost overflowing with coal. The heat was nearly unbearable before Marco closed the door. The Eluosi darted to the tool bench and returned with a long spike and a pair of pliers. He jammed the spike through the holes designed to hold a padlock on the door when not in use, and bent both ends so the door could not be opened. He quickly studied the simple controls above the door, then shut off the relief valve, opened the air intake to maximum, and smashed the temperature warning gauge. He turned away, then paused and turned back, pulling something out of his pocket and placing it on the top of the door. Shan recognized it. The plain steel ring that Nikki had worn.

There was no point in protesting, no way to stop what Marco had set into motion, no possibility of asking the Maos to stay and find the waterkeeper in the chaos that was to follow. If any of them were found near the camp they would probably be held, even summarily shot, for committing sabotage.

The Maos were waiting at the truck. Shan stared into the inner wire once more, and sighed.

"I'm sorry, Johnny, Marco said. It's what I do. Now go. Go quickly."

The Maos were ready when he returned. He said nothing about the boiler until several minutes after they had left the gate. Fat Mao listened, then rapped on the window and Ox Mao slowed the truck. Just as he rolled down his window to speak, an explosion shook the valley. The truck rocked. A boulder on the slope above dislodged and rolled past them. Ox Mao accelerated up the hill at the end of the valley and stopped the truck. They could see the camp clearly, no more than three miles away. Huge flames reached into the night sky. The boilerhouse and warehouse were engulfed in flames. Burning debris could be seen blowing across the compound. Moments later the administration building began to burn.

Thirty minutes later the Maos were pacing anxiously around their cellar, arguing among themselves, offering plans and rejecting them, suggesting what the knobs and Brigade might do next, seeming to make themselves more nervous with each suggestion. Fat Mao kept reminding them that the Red Stone clan was being processed for dispersion within hours and now their plan was impossible. Ox Mao said they should be celebrating. Swallow Mao sat at the table, staring at the blank computer screen.

Shan watched for a quarter hour from his seat on the stairs, then took a stool at the table. "Your plan. If it is impossible now, then you can tell me what it was. I know it had to do with trucks, like the one Red Stone tried to steal."

Fat Mao frowned but shrugged and explained. The herds were being shipped to the north, in four big livestock trucks. All of the personnel assignments were finalized– the Kazakhs were to go to towns, to Brigade factories, mostly. Swallow had obtained all the details from the Brigade computers. Mao drivers had been arranged for the four trucks. "But the trick was this," the Uighur said. "Truckloads of livestock are sold by the Brigade to Kazakhstan all the time. A dozen trucks are booked to go across the Kazakh border this week, west on the highway to Alma Ata. Swallow got the shipment numbers, the travel permit numbers, which have all been approved and processed. The border guards have the numbers, for verification. Jowa helped us plan everything. Tonight Swallow put in a new disc, for when the office opens tomorrow. Swallow's name will not be attached to any file. Some other clerk will get the file and transmit the travel confirmations to the Brigade headquarters. The four Red Stone trucks will be cleared by the computers to go to Kazakhstan. Those four will arrive at the depot that is receiving the Red Stone sheep, because Mao drivers will take them."

"And when the trucks leave with the sheep, the clan will be with them."

Fat Mao shrugged. "It's a small clan. There's land in Kazakhstan for those displaced from China. They will get new pastures, with other Kazakhs."

"But trucks get inspected. First the papers are checked, then the cargo is checked."

"Which is why timing was so important. Border guards get bribed all the time. At a certain time two days from now a certain guard sergeant was going to be in charge of inspecting four trucks. He would handle the clearances himself. The papers would be fine, he just won't look at the cargo. He's used to black market goods. Marco recommended him."

"Except now the data won't get sent because the disc burned in the fire," Shan said.

"All they can do now is take their factory jobs and hope we can find some other way later."

Shan studied the faces of the Maos. The excitement that had been there when they first saw the flames of Glory Camp had been replaced with expressions of defeat.

"The copies of records from Glory Camp," Shan said to Swallow Mao. "Do you have the cemetery records?"

She nodded slowly.

He turned to Fat Mao. "Can you get money? Maybe four Panda coins."

The Uighur nodded. "We use them with people across the border. They all prefer to deal in gold."

Shan quickly outlined his plan. "The only problem," he concluded with a sober tone, "is that Akzu and the others, they all have to die." Marco would take the Kazakhs out with the Americans, with four more gold Pandas for four more boats. The difficulty was that the Brigade couldn't know, Rongqi couldn't allow anyone to think the Kazahks could defy the Poverty Eradication Scheme. So the names and identity numbers for the Red Stone members would be switched with the names and identity numbers of long-dead prisoners. Recordkeeping would be chaotic in the aftermath of the fire, Swallow Mao confirmed. An emergency operations center would be created, and she would be assigned there, giving her a chance to replace the cemetery records with the new disc. The Kazakhs would have officially disappeared. And the records would be changed to show that the correct number of names were transported with the others as part of Rongqi's program, transferred onto Brigade factory headcounts. In his Beijing career Shan had investigated more than one government factory system where favors were distributed in the form of payroll identity numbers for nonexistent employees, since managers could keep the wages and no one would complain. It took no stretch of imagination to believe that Rongqi already distributed patronage in the form of such profitable ghosts.

The Maos debated the risks for nearly an hour, then Swallow chided them all. "The biggest risk is mine," she announced and sat at the computer with a new set of discs. A moment later the Glory Camp cemetery list was on the screen, then the list of Red Stone clan members assigned to the Poverty Scheme. They watched as she began tapping the keys, and one by one the members of Red Stone clan were buried at Glory Camp.

***

When they arrived at Stone Lake just after dawn, a silver camel stood in the shadow of the long dune that ran along the western edge of the bowl, beside a large shape under a blanket. They let Marco sleep and sat thirty feet away, near the top of the dune, three hundred yards from where the road led into the camp. Fat Mao had brought them and offered to stay, looking toward a toolbox in back of the truck. Shan had seen the cold anger that had settled over him and suspected the box contained weapons. He asked the Uighur to leave.

"You need a plan, in case the boy makes it here and the knobs come," Fat Mao protested.

Shan stared at him for a moment. "The boy won't come here because the Maos will find him first."

"There's been no sign of him. Those dropka he's with, they're like wild animals. Stealthy. We may not intercept them."

Shan sighed. "Then everyone will flee with the boy and the Jade Basket," he said quietly, so only the Uighur could hear. "I will distract any knobs who come."

"Distract?"

"There is something else Bao wants in addition to the gau or the Americans."

Fat Mao studied him a moment. "You."

Shan shrugged.

"Not everyone has to be a victim," the Uighur said with a frown. "Not every time." There was frustration in his voice and, oddly, a tone of apology.

"Look for the boy for another hour," Shan said, "then go to Red Stone clan. They need you today too."

Fat Mao frowned again, then turned and left.

The last day had arrived, the day Rongqi and Ko had dreamed of, the final implementation of the Poverty Eradication Scheme. Akzu had to be found and told of the new plan. The Red Stone herds had to be surrendered, with their tents and everything else being taken over by the Brigade. For the only way for the clan to be free, and together, was to give up everything in life they had valued, except life itself.

Gendun laid back on the sand and exclaimed over the shapes of the clouds. Lokesh, as he had countless times before, laid out the possessions of the Yakde Lama and studied each one. They had all their bags, ready to leave for Tibet. Shan pulled out their old pair of binoculars and cleaned the lenses on his shirt, then handed them to Jowa, who crawled to the top of the dune and began to watch.

After an hour Jowa whistled. Kaju had appeared, walking alone down the road. They lay on the sand behind the crest of the dune and watched as he stopped at the building skeleton that swayed in the wind, tied something to one corner post, then tightened it and secured it to another post. A string of Buddhist prayer flags, the flags, Shan suspected, from Lau's office.

The Tibetan stopped and stared at the flags after he had fastened them, as if seeing prayer flags for the first time in his life, then turned and walked slowly toward the garage building. Shan stood and waved and in a few moments Kaju had joined them.

He greeted them in Tibetan, not Mandarin, and for the first time since Shan had known him continued the conversation in his native tongue. There had been no contact from Micah, he reported, no chance to warn him away. But in the night, Kaju said hopefully, there had been many sirens and many knobs had rushed out of town. Maybe they were gone, or at least distracted. Maybe Bao would forget one small boy in the face of whatever Public Security emergency had arisen.

They were sitting in a circle, listening to Kaju explain how he planned to one day return with all the zheli and truly see the fossils, when someone threw a plastic bag of raisins into their midst. They looked up to see Marco's broad face, looking grim but determined.

He squatted by Shan with a handful of raisins. "Took an hour for them to decide to let the prisoners out to fight the fires," he reported without emotion. "Fools. By then all they could do was throw sand on the embers. Nothing left but smoldering bags of rice where the warehouse was. No administration building. The little house at the gate, even that." There was no victory in his voice, but when he looked at Shan an odd glint rose in his eyes. "Nikki approved," he said in a low tone, and nodded as though to acknowledge that although it might not feel like victory, it did feel like completion.

As Kaju stood and walked along the top of the dune, watching for Micah, Lokesh lifted the raisin bag and passed it around. Breakfast. "You'll see," Kaju called out to Shan. "It's only Bao. If he comes and tries to take the boy it will be the proof I need. I'll go to Ko," he said as he stepped nearly out of earshot. "Ko will know what to do." Shan and Jowa exchanged a glance. Kaju still refused to accept the truth.

As Marco ate his raisins Shan explained the new plan for the Red Stone clan. The Eluosi didn't argue. "That old Tibetan hunter at the border, the one with the coracles, only way he'll do it now is if he sees I'm with them," the Eluosi said and looked at Shan. "I'll need help."