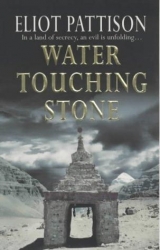

Текст книги "Water Touching Stone"

Автор книги: Eliot Pattison

Жанр:

Полицейские детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 13 (всего у книги 38 страниц)

Suddenly the door exploded outward, propelled by the weight of a man who collided with Shan. The two men landed in a heap in the sand and the stranger seized Shan's throat in both hands and began to squeeze. Shan gasped feebly and tried to buck the man off. His assailant responded by releasing his throat and pounding Shan's chest with his small, hard fists as Shan twisted and turned, trying to escape.

"Thief!" the man shouted at Shan in a shrill voice.

Two more hands appeared, grabbing the man's shoulders as Shan slid away. Jakli held the man for only a moment, then he squirmed from her grip and crawled toward Shan, his eyes wild and murderous.

"Hoof!" Jakli screamed. "You have to stop!" She kicked the man's back, without effect, then kicked again, harder, knocking him prostrate on the sand.

The action brought the man to his senses. He pushed himself up on his hands, looked around with a blank expression, then slowly rolled over and sat up, gazing at Shan and Jakli in confusion.

"Ah, it's you," the man called Hoof said dully to Jakli, and his gaze drifted toward the door. "I didn't see you," he muttered. His confusion seeemed to fade, replaced by something that Shan thought might be disappointment.

Shan felt moisture on his hand where he had tried to push the man away. "You're bleeding," he gasped, suddenly afraid he might have injured the man.

The expression on the man's face as he looked at his wounded right shoulder was not alarm, but disgust. "Robbed, and stuck in the bargain," he groused in a high voice. "Nothing but bad joss here." He had a huge nose and pale skin, with spots on his cheeks that might have been freckles. His small features came to life as he sat and studied Shan. "No one wants you here," he said with an odd hint of hope in his voice.

"You should clean that cut," Shan said, exploring his pockets for something to help the man.

"You'll have to go before-" The man's warning was cut off by the appearance of a figure in the doorway, a tall man wearing a embroidered skullcap and a brilliant green shirt from which the sleeves had been torn. He held a glass, which he was wiping with a scrap of cloth.

"Damn you, Osman!" Hoof squealed. "Some dog's whore stole my pouch." As if having an afterthought he raised a hand, which was red with his blood. "And stabbed me. A man isn't safe!"

The man he had called Osman grunted, and his eyes lit as he saw Jakli. He raised his head with a broad smile, then noticed Shan. The smile disappeared. He threw the rag at Hoof and stepped back into the shadows.

"Sons of pigs!" Hoof cursed and threw the rag back at the door.

Shan tore a strip from his undershirt and tied it around the man's wound. As he did so the man's expression softened. "You'll need to leave. I could help you," the man said in a new, confiding tone. "I am called Hoof. I'm a good Tadjik. I know the desert. I have Chinese friends. I'll take you to town. You'll be safe in a town."

"He's safe where he is," Jakli said, stepping forward so that she towered over Hoof, who was still sprawled in the sand.

"Sure he is, sure he is, if he's with you." Hoof scuttled backward on all fours, crablike, out of Jakli's shadow, then leapt up and darted back into the building.

Shan looked after him. "His name is Hoof?" he asked Jakli.

She sighed, watching the doorway with worry in her eyes. "It's a way of some of the old herding clans. A baby is named after the first thing the mother sees on the morning after the birth." She motioned him toward her, as if to lead him away from the building.

But Shan followed Hoof inside.

At first it seemed he was entering a cavern. He stepped into an unlit corridor five paces long, with deeper shadows that hinted of alcoves on either side. In the dim light he studied the sand floor of the corridor as he moved down it, trying to understand what had just happened to the Tadjik. A stone wall faced him at the end of the hallway. A ghost wall. The hands that had constructed the structure had been guided by a geomancer, one of the shamans who were more important than any architect or carpenter in building even the simplest stable in the traditional kingdoms of northern Asia. Practicing his art of feng shui, a geomancer had long ago directed the placement of a wall facing the door, because evil spirits only flew in straight lines. The main entrance itself, Shan realized, opened to the south because those same spirits lived in the north.

The scent of lamp oil and and cinnamon hung in the air. He heard laughter and a loud voice telling a ribald joke in Mandarin.

At the wall he turned to the left, into a short corridor that ended in a small arched doorway. Shan stood in the arch and stared through a miasma of tobacco smoke into what appeared to be the public room of an inn. The chamber was illuminated by a dozen large candles and four kerosene lanterns, two of which were suspended from the wooden beams over a large table by loops of what looked like telephone cable. The table, which stood ten feet away, had been raised by piles of flat stones under its legs, so that it stood at the waist of the man who had briefly appeared in the doorway, the tall man called Osman. He was leaning on the makeshift bar beside a basket of dried figs, a stack of flat nan bread and a collection of bottles containing liquids, most in various shades of brown. Drinking glasses, many of them cracked and dirty, were stacked precariously at the edge of the table. Behind Osman a large shaggy grey dog lay on the floor, asleep.

A dozen men were scattered around the room, seated at several large wooden crates that functioned as makeshift tables. The wounded Hoof shared a bottle with another man at the table furthest from the door, holding his arm, scowling at Osman as he muttered something that made his companion laugh. A small, exquisitely carved table stood in the center of the room, unoccupied. On it stood an ornate chess set and beside it was a large, filthy, overstuffed chair that had the appearance of a pincushion from all the straw that had been jammed into the holes in its upholstery.

The clamor of voices abruptly ceased as he stepped into the room.

Shan was the only Han.

With the eyes of half the men fixed on him, Shan moved uncertainly to an upended box beside the bar. As he sat and reached for one of the figs, his observers turned away. The volume of conversation rose again. Two men rose to refill their glasses, giving the stuffed chair a wide berth. Shan saw that the sleeve of the bright red shirt worn by one of the men appeared empty, and he looked closer. The man was missing an arm below the elbow.

Through the smoke Shan studied a mural painted on the wall behind Osman. It contained figures with long faces and beards, the faces of Europeans or perhaps Persians. They were riding donkeys with heavy packs toward a man who awaited them under a grape arbor. One of the figures had its eyes scratched out, a familiar sight in the lands of the Muslims, whose holy law forbade images of humans. A nail had been driven into the plaster above the mural to support a small framed black and white photograph of a horse. In a niche beside a curtain that hung at the opposite end of the bar was a stone Buddha, badly cracked, into whose pursed lips a cigarette butt had been jammed. A hand-lettered sign hung on the wall above it, proclaiming This Bar is Nei Lou. On the wall past the curtain was suspended a white flag with a crescent moon and a single star.

"Do you have tea?" Shan asked.

"What you see is what you can have." The man called Osman held up a leather drinking bladder. "Kumiss," he said, then pointed with it toward the bottles. "Bai jin. Mao-tai. Beer. Vodka." He had a gravelly, impatient voice. "Two yuan."

"Two yuan?" Shan asked in disbelief. Two yuan would buy a meal for an entire family in many parts of China.

"Our special rate for eastern visitors."

"I'll just have water."

"Three yuan."

Shan felt someone at his shoulder. "Two teas, Osman," Jakli said.

The bartender frowned. "He's with you?"

"With me. A friend of Auntie Lau."

"He's here on your word?"

Jakli said nothing. She stared at him for a moment, then stepped to the wall and pulled the cigarette butt from the Buddha's mouth, throwing it to the floor. "Two teas."

Osman considered her silently, then leaned down and pulled a large black thermos from the floor. He filled two of his glasses with steaming black tea.

"Nikki?" Shan heard her ask in a quick, anxious tone as he surveyed the room. "I don't see his men."

The question seemed to put Osman at ease. "Not yet. Tomorrow, maybe. One last caravan. Soon, be sure of it." The tall Kazakh studied Jakli's face, which had suddenly clouded with worry. "He's fine, girl. You have my word. No one catches Nikki," he added with a smile that exposed a silver tooth. "No one but you." He poured another tea, then raised it to his own lips in a toast. "To dark nights and sleeping sentries," he said with a small grin.

Shan looked back at the one-armed man as he returned to his seat with his glass refilled. He had heard in prison about men escaping the gulag and chopping off their own arms above the tattoo to destroy the proof of their genealogy.

Jakli pushed her stool closer to Shan, as though to shield him, and they quietly drank their tea while Osman wiped glasses at the opposite end of the bar. As Shan surveyed the occupants she quietly explained the rules of the community. No one removed artifacts from the sand, unless they were to be kept and used at Karachuk. No one built anything that might appear like modern construction to aerial surveillance. No one built anything, period, without Osman's approval. No one burned wood from the ruins, for fear of telltale smoke, and for the need to preserve what was there. He asked about the flag. From the Republic of East Turkistan, Jakli explained, in which Osman's grandfather had served as a vice-governor in Yoktian.

"This is Osman's town, then?" Shan asked Jakli in a low voice, keeping his eyes on the man behind the bar.

"My ancestors lived here," Osman interjected loudly and stepped closer. "It's my right." His eyes locked with Shan's, as if he was waiting to be challenged, then after a long moment he turned to Jakli. "Where's Akzu?" he asked.

"With the Red Stone. The Poverty Eradication Scheme. Less than two weeks now."

Osman grimaced. "The bastards. I told him. Bring the clan here." He clasped his hand tightly around a bottle and for a moment he stared at it. "This is the way it ends," he said grimly, "with corporations and Chinese giving speeches." He looked back up at Jakli. "I told him, better yet, bring me Director Ko. We'll make him right at home." The men at the nearest table laughed and Osman acknowledged them with a thin smile, then turned back to Shan. "You have business with Nikki?" he asked in a voice that was filled with suspicion. "Something special to buy?"

"I came because of Auntie Lau," Shan said. "She was-" But he saw that Osman was not listening. The bartender had sensed something, a movement, a shadow nearby. He was slowly turning toward the curtains that hung at the far side of the bar, his hand moving under the table, as though reaching for something. The grey dog was on its feet suddenly, growling.

The room grew silent again as a whispered warning shot through the crowd and the occupants of the tables looked up anxiously at the rear curtain. A finger, a very large finger, appeared near the top of the curtain and slowly began to push it aside.

Osman instantly relaxed. He brought his hand back from under the table. Several of the men in the room gave a small cheer. A bald man wearing a fleece vest rose and made an exaggerated bow toward the curtain. Others raised their glasses over their heads. The dog shot forward, wagging its tail.

"Marco!" Jakli exclaimed with sudden joy and ran to the stranger's outstretched arms.

Shan would have been at a loss to describe the man who entered the room. Many might have simply used the words big and Western. But to call the bearded man big would have been like simply describing a bear as big. And certainly he had the face, the features, the build of a Westerner, but there was something in the man's countenance that was not of the West. His eyes were blue, but they roamed across the room with the same hard, wary intelligence Shan had seen in Akzu and some of the other men of the clans. His skin bore the same leathery creases Shan had seen on the clansmen. There was one obvious difference, however. The stranger's face carried lines around his eyes that said he was a man who often smiled.

"Comrades!" the man thundered in a boisterous, mocking tone as he released Jakli from his hug and pulled her with him toward the bar. "Your commissar has arrived! I am going to instruct you in good socialist thought! I am going to clamp your loins so you don't have children! I am going to ration your belches, your bottles, and breaths! I am going to register your lice and tax your horses' piss! And you'll crave every minute of it because it is all for the beloved People's Republic." He spoke in perfect Mandarin, and pronounced the last words like shots from a cannon. His audience laughed raucously.

A huge grin settled onto the face of the man Jakli had called Marco. He reached into the deep pockets of the massive overcoat he wore and produced two bottles of vodka with Cyrillic labels.

"But first we drink!" The bottles were corked. He produced an expensive Swiss army knife and opened its corkscrew.

Osman tossed him a glass. "What do we celebrate now, you old bear?"

"Sure we celebrate! Because I'm alive and you're alive! Because Jakli is so beautiful and Nikki is so bold. Because we've all beat the odds and seen another harvest season. Because I'm bringing enough vodka to the horse festival to stay drunk for a week!"

Every man, even the sulking Hoof and his companion, rose and converged on the bar as Marco filled their glasses. "To smugglers!" he toasted when all the glasses had an inch of vodka in them, "Wan sui!" His shout shook the lanterns. "Ten thousand years! Wan sui for all smugglers, the most honorable of all professions." He considered his glass a moment. "We don't pretend to obey rules we don't believe in," he declared with exaggerated solemnity. "And we always give people what they want." The men at the bar slapped the big man on the back and snorted with laughter as he taunted them with a pair of worn ivory dice.

At last his eyes came to rest on Shan. "Who's this ragged little thing, Jakli dear?" he asked, with a smile that had lost its light.

"He's come to help. About the killings."

Marco's nostrils flared. "God's breath, child!" he growled in a low voice. "Surely you didn't-"

"He's not from the government," Jakli interjected quickly. "He's from Tibet."

Marco frowned, then studied Shan with a cold gaze. "A hard place, Tibet," he said after a moment.

Shan nodded. "Especially for Tibetans."

Marco gave a bitter grin and a nod of acknowledgement. "Where in Tibet?"

"Mostly, the 404th People's Construction Brigade. At Lhadrung."

"Lao gai." Marco spat the words like a curse. He swallowed what remained in his glass, then stepped to Shan's side, gripped his forearm in his huge hand, pushed up his sleeve, and examined his tattoo.

He pressed it and stretched it, then nodded his approval, as though a connoisseur of such marks. "Before that?"

"Beijing"

Shan's announcement silenced every man within earshot.

The brawny man poured himself another shot of vodka but left it on the bar as he examined Shan more closely. "A silk robe!" he exclaimed with false warmth, referring to the mandarins who had run the empire during the dynasties. Amusement was in his voice but not in his eyes. He lifted his eyebrows in mock bewilderment. "Or perhaps a palace eunuch?" The men yelped with laughter.

"I am called Shan Tao Yun," Shan said quietly.

Marco raised his glass. "Welcome to the Karachuk Nationalities Palace, Comrade Shan," he said, referring to the gaping halls built in provincial capitals for the glory of the country's multiple cultures. Low snickers rose from the tables.

"You– you are a visitor as well, I see," Shan said awkwardly, still confused by the man's Western appearance.

Several of the men laughed again.

"By the spirit of the Great Helmsman, you offend me!" Marco boomed. "I am the best damned socialist in the land! If anyone ever gave me a passport, which they won't, it would be red. With a big yellow star and four small ones," he said, referring to the emblem of the Chinese state. "I am as stalwart a citizen as can be found in Xinjiang."

"That's not saying much," Shan offered. It was a dangerous game they were playing, especially because he did not understand the connection between Marco and Jakli, and how much her protection accounted for.

Marco's grin returned. "A silk robe with a sense of humor." He leaned toward the man behind the bar. "Must be true what they say, Osman," he said in a sober tone, his eyes twinkling. "The worker's paradise just keeps getting better and better." He shifted on his seat, causing his heavy wool tunic to fall open. Two objects became plainly visible to Shan. One was a heavy silver chain, attached to a large pocket watch. The other was the biggest pistol Shan had ever seen, a revolver that looked like it had been made in the nineteenth century.

"I didn't hear the rest of your name," Shan said to Marco.

The big man looked hard at Shan. He was clearly not accustomed to being pushed. "I am called many things. But I was baptized, Comrade," he said in a taunting tone. He seemed to enjoy the look of confusion that flashed across Shan's countenance.

"Yes, baptized. By an old priest who once gave communion to the Czar. My mother chose the name, for the many strange lands she expected me to see. Marco Polo Alexei Myagov. A member of one of our country's honored minorities. The most loyal white Chinese in the land."

An Eluosi. Shan had almost forgotten they existed. Most of the Russians who had fled the Bolsheviks eastward across the Pamir or Tian ranges eight decades earlier had moved on to Shanghai, then eventually emigrated to Europe or America. Some twenty or thirty thousand, however, had stayed in Turkistan, even when another generation of communists had annexed it as Xinjiang. He had heard once that visiting certain villages in the far north of Xinjiang was like paying a visit to Czarist Russia. A few thousand of the Eluosi were still scattered among the population of Xinjiang and had even been granted special privileges for hunting and fishing on the lands originally purchased by their forebears from local warlords. Otherwise, they were a people lost to the world.

"It's many a year, I wager, since anyone has visited Karachuk from Chambaluc," Marco observed, using a name for Beijing Shan had not heard since he was a boy, the name given to the city during the Yuan dynasty, when the khans, linked by blood to the Turkic peoples of Xinjiang, controlled all of China. It was, Shan realized, the name many of the original inhabitants of Karachuk would have used. Marco's voice was warmer but his eyes remained suspicious. "What did you do there, before you earned your tattoo?"

"I was with the Ministry of Economy," Shan said self-consciously. "An inspector."

"But you inspected the wrong people."

"Apparently."

Marco's laugh was too large for the room. It rattled the stacked glasses. He poured himself another vodka and gestured toward Shan's still untouched glass.

"Well, Comrade Inspector, here we're all just faceless members of the glorious proletariat. Gan bei," he toasted, and drained his glass.

Shan stared at his glass, then lifted it under his nose. It was the closest he would knowingly get to tasting the hard liquor. It was not because it would violate the vows of the monks, which he had not taken, but because somehow it felt as though it would violate his teachers who still sat behind prison wire in Lhadrung.

Marco surveyed the room as he drank. Suddenly his glass stopped halfway to his mouth and he spat a curse, then sprang to the chess table in two long strides. He let out a second sound that was not a word, but a roar. "She's gone!" he barked.

Osman trotted to the table. "Impossible. Your empress was there last night. I was sitting here, thinking about my next move."

Marco's head swayed like that of an angry bull as he surveyed the room. "Osman and I have played this game for six months," the Eluosi declared loudly, to no one in particular. "In the winter, I sometimes bring food and fuel and stay for a week, at this table."

Shan stepped to his side. The game pieces were of ancient bronze. One army was red, one green, identified by small rubies and emeralds inlaid on the head of each figure. The stones were heavily scratched. Shan did not have to be told that the figures had been dug out of the desert sand.

"My empress!" Marco bellowed again. Shan saw that the ruby-capped counterpart to the green queen on Osman's side of the board was missing.

Osman leaned toward Marco's ear and spoke quietly, nodding toward Hoof.

"Mother of Christ!" Marco exploded as Shan retreated toward Jakli. "Two thefts! You swine!" he shouted at the general population of the room. "Lau's body barely cold, and now this! I won't have it. I should kick every man jack one of you to whatever hell you believe in. We have honor here. Shepherds. Caravan men. Smugglers. We treat you like brothers and sons. Where in hell do you think you are? Urumqi? Yoktian?"

"That Xibo from Kashgar was here," Osman offered anxiously. "Just released from detention. Probably it was him. Nobody followed Hoof out. But the Xibo left five minutes before Hoof. Probably took the queen, then jumped Hoof for his pouch. Miles away by now."

"The thief is still here," Shan said, very quietly.

Marco did not seem to hear him. He moved to the bar and took a deep drink directly from his bottle, then turned to Shan as he wiped drops of vodka from his beard with his sleeve. "Again."

"I believe the man who did this is still here," Shan said in the same low, self-conscious voice.

Marco stared at him in brooding silence. "An inspector, you said. So just like that, the inspector knows who the criminal is." He looked out over the men in the room. "This isn't Beijing, you know. People are not simply guilty by decree here."

"It's just a matter of understanding the facts," Shan offered. "When the facts are properly understood, justice may find a way."

"Justice?" Marco asked incredulously, his thick brows rising. "Did you say justice?"

Shan looked at Jakli, hoping for help. But she was staring nervously at Marco.

"Here is a strange creature for you, Osman," Marco said, his voice as sharp as a razor. "A silk robe who worries about justice." He put his hand around the nearly empty bottle and turned to the tables. "Gentlemen of the court! We have an entertainment. The renowned detective Shan Tao Yun from the court of Chambaluc is about to show us astounding feats of reasoning and deduction! No doubt he is a descendant of the great Judge Dee, magistrate of the Tang dynasty," he barked out, referring to the legendary investigator whose exploits had been the subject of folktales for centuries.

Marco whispered to Osman, who retrieved a long club of black wood from the corner behind the bar, then stood by the corridor to the front door.

"But I can't-" Shan protested, thinking of making a dash for the door himself.

"More crime has been committed among our own," Marco spoke in a tone that told everyone that the joking was finished. "As if what happened to our Lau wasn't enough. There will be an end to it," he vowed with a sound like a snarl.

Shan realized that he was not being offered a choice. He stepped back to the bar, his eyes on the little Buddha. "I would like," he said in a tentative, uneasy voice, "another cup of tea."

Osman smiled, as though pleased with Shan's discomfort, then stepped away from his post by the door long enough to pour the tea.

"I don't wish that anyone be hurt," Shan said after a sip from the cup. This was Turkistan, he reminded himself, where retribution was always a few steps ahead of forgiveness.

Marco merely stared at him.

Shan sighed. "Something happened in here a few minutes before I arrived. An alarm. A signal. A new arrival, perhaps."

"Nothing," Osman said in an impatient tone.

"Sophie," the bald man in the fleece vest called out. "I said I heard Sophie coming."

Marco raised his eyebrows toward Osman.

"True enough," Osman said. "But no one else heard anything. We didn't expect you."

Shan looked at Marco. There was someone else with the Eluosi, someone with the improbable name of Sophie. "The possibility that you were coming scared Hoof," he said.

"Because?" Marco asked.

Shan replayed the events in his mind. Hoof had not simply been trying to flee. He had been wounded and then had lied, trying to blame Shan, and then had given up when he saw Jakli. Shan had not understood the disappointment on the Tadjik's face. "Perhaps because he had taken something. Because he had to lose it, or hide it now that you were coming. He only had a few moments."

Hoof had stood and was inching closer, his compnion behind him. "I've ridden with Nikki," the little Tadjik blurted out. "I have groomed your animals. This Han insults me. He hates our kind."

Marco silenced him with a raised hand, then turned back to Shan.

"All right, tai tai," Marco said. Tai tai, esteemed one, was a form of address reserved for the most venerable of the mandarins.

"Where does Hoof wear the missing pouch?" Shan asked Osman. Hoof retreated to stand with his back against the wall, looking toward his companion, who seemed to be edging away, back toward their table.

"It was big," Osman answered, "it hung from his belt. His left side."

Shan nodded. "Perhaps this is what happened. Hoof had the empress in his pouch. When Marco was coming he had to be rid of it, because Marco of all people would notice it gone. Get rid of it but not get rid of it. Hide it, so he could get it later. He cut off the pouch and hid it in the corridor. Through the opening in the door he saw me, a Han, coming. Thinking he could blame it on me, he cut himself and threw himself on me as I opened the door."

"Someone could have been waiting with a knife in the corridor," Marco suggested. "The Xibo."

"Exactly," Hoof said eagerly. "He stood in front of me, he rushed me." His eyes did not move from Marco.

Shan shook his head. "That floor in the corridor had half an inch of sand," he observed. "It would have left signs of a struggle. But look at it, you won't see any. And he blew out the flames on the oil lamps as he went down the corridor, to make it appear an ambush had been set. The lamps had just been extinguished when I entered. I could smell the oil."

"True," Osman added. "They were dark when I went out to see who was shouting."

"But surely he wouldn't cut himself," Marco countered.

"Not a bad cut, just enough for blood to show," Shan said and saw that Marco was not convinced. "This is how it happened. The cut was on his upper right arm. A thief's knife would have been low and to Hoof's left, to cut away the strap of the pouch, not high and to the right. Hoof held the knife in his left hand and cut his own right arm. I was watching everyone drink. Hoof is the only man in this room who is left-handed."

Osman nodded. "Bad upbringing. A good Muslim is always trained to use his right hand."

"So what?" Marco asked.

Shan extended the index and middle fingers of his left hand like a blade and made a chopping motion on his upper arm. "He cut himself like this. A thief would have swung low, cut his belly on the same thrust maybe, but not the upper arm." Shan shrugged, and looked toward the shadows of the front corridor. "There must be shelves in there or niches for the oil lamps."

Osman nodded, pulled a lantern from its hook, and led them into the corridor. The original builders had provided four deep concave shelves for lamps. The first two niches were nearly obscured by cobwebs behind the lamp. At the third the webs had been recently broken. Marco reached in and pulled out a pouch. Making a small, angry growling noise, he marched back into the room and snapped out Hoof's name.

The Tadjik stood with his back to the wall, alone, abandoned by his friend. Marco held the pouch by the man's nose for a moment, then reached into it and pulled out the emerald queen.

Hoof's hands began to tremble.

Marco upended the pouch on the bar and out tumbled two large round objects, both the same size, each wrapped in white paper. Marco shook one and an apple fell out. "You stole from me," Marco growled as he extended the queen toward the Tadjik. "You stole at Karachuk. You stole when we were still mourning our lost aunt."

Hoof looked back at his companion, who stared at him stonily.

"Say it," Marco boomed. "Say you stole."

"I st– stole," the Tadjik murmured.

"Why?"

"Last year, you hit me. I was unconscious for an hour. My head hurt for a month."

"You insulted my camel," Marco shot back.

No one laughed.

Shan picked up the second round object. He pulled on the edge of the paper and a ball rolled out, a three-inch white leather ball joined by heavy reddish seams. Although Shan had never seen such a ball before, it looked vaguely familiar. He stared after it as Osman picked it up, shaking his head at Hoof, and placed it on top of one of the glasses, then tossed the crumpled paper into a basket that was nearly filled with empty bottles.

The men in the room began moving out, trying to look inconspicuous, their heads turned away as though they had seen something in Marco's face and were scared of it. Only six remained by the time Marco noticed. "No!" he called out. "Stay and witness!"

The big Eluosi pointed to the floor in front of the bar and Hoof stepped forward, cowering, his arms half raised as if he expected to be struck. "Here is what you will do, Hoof the thief," Marco announced as he paced around the Tadjik. "The uncle of Osman, he has a camp near the Wild Bear Mountain, at the ford of Fragile Water Creek. You will go there. You will tell them my words. They lost a son to fever this spring. They are outside the county, not in the Poverty Scheme. Which means they are going to winter camp soon. They will need help to gather fodder, to milk the goats. If you leave before they take the herds to spring pasture, I will know it. We will all know it, we will understand that you are indeed someone without honor. And then you will have no protection. Do you understand?"