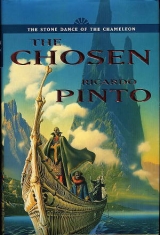

Текст книги "The Chosen"

Автор книги: Ricardo Pinto

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 9 (всего у книги 38 страниц)

The drum beat dolefully under their feet. The two wings of obedient oars plunged into the sea and then flew out sowing curves of foam. The ship carried them into the tower's cold shadow. At its base gaped a blacker mouth. Only the curving of its high arch bore witness to men's work. Above them flickered a screeching shroud of birds. The sky began to disappear as the ship passed under the pot-bellied rocky swelling. They could smell wet rock. Grey-blue stone rose around them from the sea and made the ship seem as fragile as a poppy.

'If she touches the sides she'll shatter to driftwood,' whispered Tain.

The tunnel arched above them. Bird excrement streaked its walls. A pair of sky-saurians flapped screaming out from the blackness. Dank shadow swallowed the ship and made the boys stand closer together.

The drum fell suddenly silent. Its last beat echoed away to nothing. There was a terrible scraping. Carnelian felt the pull of Tain's hand on his cloak. He dared to look over the rail. He watched the bend then splinter of a shadowy oar that had not been drawn into the hull quickly enough. Behind them the captain was shuttling from side to side, shouting orders, guiding them through. Slaves thrust bronze-shod poles against the rock. Straining, leaning against them, with sparks, cursing, they coaxed her down the narrow channel.

Ahead, surprising daylight glowed. There was a shock of impact and a gasp from Tain. The ship scraped herself along the rock. Panic-edged cries echoed as, laboriously, she moved out of the tunnel. Carnelian and Tain, their eyes already accustomed to the dark, were dazzled by the light. Carnelian squinted past his hand. The Tower in the Sea was hollow. The ship was drifting in yet another wide, almost circular harbour enclosed by stone. Its wall was pierced all around the water's edge with archways in which he could see other ships lurking half drawn out of the waves.

Like rattling spears, the oars thrust out, then hung limp in the water. The drum sounded a dull thud that vibrated through the deck and then rose up echoing round the walls. The ship came alive again.

The rhythm was dismally slow as she swam across the inner harbour. The further wall drew nearer. The captain gave a cry and she swung towards the cavern of a ship-house where some faint lanterns burned like eyes. Carnelian felt her ail, her heartbeat slow. At least half her oars rasped back into her hull. She slid ponderously forward towards the shiphouse. As she passed the gateposts many of the crew flung themselves over her edge onto the netting that covered the inner walls. There was a sudden lurch. She juddered still. Carnelian and Tain held each other up. The crew swarmed along the netting into the darkness further in. They returned struggling with two enormous hooks of bronze. Behind them hawsers snaked out from the dark. The hooks bit somewhere into the ship's hull. A grinding came from the shiphouse depths. The hawsers tautened and then, with a shudder, the ship was dragged screaming into the blackness.

Her deck began to slope upwards at an angle. Carnelian held on to a rail. She bellowed as her hull scraped against the ramp. The captain struck the right-hand hawser with a billhook and made it sing. He scrabbled across the leaning deck and did the same to the other. Its voice was slightly higher. 'Starboard!' he shouted into the darkness. The ship was coming up out of the water. The captain lumbered back and forth. Each time he sounded the hawser like a bell. Each time he flung a command into the darkness.

When the dragging stopped at last, Carnelian was able to hear the mutter of voices. Torches came alive all along the walls. The crew flung ropes from the ship's sides that others on the netting caught and looped round the mooring knobs studding the wall. She settled, gave one last stuttering groan and then fell silent. With an ache, Carnelian remembered her flying wild and free across the waves. Now she was tethered like a slave, deprived of the water that gave her life.

THE TOWER IN THE SEA

Characteristics required of a legionary tower are:

Firstly, that its personnel shall be segregated according to their kind: the marumaga shall not be quartered with the Chosen; the barbarian shall not be quartered with the marumaga; the barbarian shall be maintained in isolation from the huimur.

Secondly, the manner of this segregation shall be, if possible, in descending strata, otherwise in wall-separated courts.

Thirdly, the spatial elements of this segregation shall have no communication with each other save by means of linking stairs or corridors.

Access to these must be controlled by suitable military gates that are lockable from the stair or corridor.

(from a military codicil compiled in beadcord by the Wise of the Domain of Legions)

'One always likes to make a grand entrance,' said Jaspar as he walked towards Carnelian, leaning forward against the slope of the deck.

Carnelian gave Tain a little shove. His brother moved off down the deck, ducking an obeisance as he passed Jaspar. The Master watched him go. 'My Lord seems quite attached to that waif.'

Carnelian disliked the tone in Jaspar's voice. 'He is my brother.'

Jaspar glanced back at Tain. 'Your brother?'

This mode of entry seems rather unsuitable for the Chosen,' Carnelian said, to change the subject.

This is a vessel of war and not intended for the use of the Chosen. She hunts pirates.' Jaspar vaulted up onto a ledge. He tucked his cloak up between his legs. His mask looked down at Carnelian. 'Would you like my hand, cousin?' He offered one.

There is no need.' Carnelian emulated the other's vault.

'My Lord now stands upon the Three Lands.' Jaspar turned away. 'Presumably, one is supposed to hold onto the ropes.'

Carnelian looked down at his feet, considering Jaspar's words. Below him people were moving up the deck. Towering among them were the other Masters, made silhouettes by the bright undulating water of the harbour.

Carnelian drew his cloak tight against the clinging damp. The tarry air caught his throat. Jaspar was already some way along the ledge. Carnelian followed him, using the net as a support. Its oily rope stuck to his hand. As he passed the baran's curving prow he averted his eyes from the leering horned figurehead. Ahead, pale light sketched an archway in the wall. A dull clang made him peer deeper into the shiphouse. He was sure that he could make out things like hunched men. He hurried forward to tug at Jaspar's cloak. 'What are those, there?' he whispered.

Jaspar's mask looked back at him. 'Most likely they are sartlar. Be thankful the blackness conceals their fearful ugliness.'

As the Master passed through the archway, Carnelian stole another look into the dark. He saw a glimmer like eyes before, with a shudder, he followed him.

'Where are the guides?' snapped Aurum. Each word quaked the sailors who had come with them to light the way. Their torches made the escort of shadows shake with fear.

This is intolerable,' said Vennel.

'Perhaps, my Lords, we should wait for our tyadra to disembark,' said Suth.

Here and there cavern stone showed between the sail parchment shrouds, the stacks of capstans, cleats in clusters, blocks, coil upon coil of rope. Hawsers swagged down from the darkness. Above their heads, a single mast bellied off in both directions. Far away the passage narrowed to a dim lozenge of light.

'I will not wait for my guardsmen,' said Aurum. 'You there!' He strode towards one of the sailors, pointing an enormous finger. The creatures dropped to their knees in bunches, their torches spurting the Masters' shadows up the walls like ink.

Aurum spoke over their terror. Take us to your Master's halls.'

They cowered away from him. Unblinking eyes all round were fixed on Aurum. Carnelian saw a dark hand regrip its torch more tightly. He remembered similar hands scrubbing blood from the grating of the deck.

Aurum strode among the sailors, scattering them like pigeons. 'Do you not hear my command? Lead us up, I say, to your Master's hall.'

'He pushes them beyond terror into panic,' said Jaspar in a loud whisper.

Relentless, Aurum herded the sailors and their light before him, threatening to leave the other Masters in blackness. Suth and Vermel strode after him. Carnelian was reliving the horror of the massacre but made to follow when Jaspar put a hand on his arm. 'A lute string already taut should not be tightened further lest it snap. Better to pluck it till it slacks and needs retuning.'

'My Lord has such exquisite sensitivity,' hissed Carnelian. It was only when he reached the others that he became aware that he was grinding his teeth.

The slaves found them a stairway winding up into the blackness. Carnelian had to feel for each step. The Masters plugged the stairwell with their bodies, squeezing the light into a random flicker. To make it worse the stairway narrowed and rock rasped his cowl, eventually forcing him to bow. After the cabin, Carnelian had acquired a loathing of confinement and he was relieved to reach the top.

Although the sailors held their torches aloft, the flames were at his eye level. He wished they would hold them steady and not cower every time he raised his hand to shield his eyes from the glare. The air was stale with the odour of oil and sweat and fear. Roughly hewn pillars bulged under a ceiling low enough to stoop Aurum. Columns faded off like trees in a moonless winter forest.

This is probably not the Legate's hall,' said Jaspar. Vermel turned on him. 'I find your levity distasteful, my Lord.'

'One shall refrain from telling my Lord what one finds distasteful,' said Jaspar.

Carnelian noticed movements out of the corner of his eye. The darkness rustled with whispers.

'Evidently, this is not the upper stratum,' said Aurum. 'We have not climbed nearly high enough. But I swear by the Twins, my Lords, that if these slaves do not quickly find the proper stairway I will empty their blood upon the floor.' His mask turned upon the sailors, sweeping their line with its serene malice.

A torch sparked thudding to the floor and Carnelian saw the man who had held it melt away. The dark mounded with many heads. There were other sailors there, many others, ringing them with their splintered mirror eyes.

More torches hit the ground. Carnelian became convinced that he and his companions were being surrounded, that they had been led into an ambush. He glanced quickly round with a warning on his lips but the impassive golden masks muted him.

Suth stooped, scooped up a torch, then another. He thrust their glare into the faces coming into the light. The sailors fell back moaning, bowing, tucking their heads away into the shadows.

Following his father's lead, Carnelian plucked up a torch.

His father continued to swing fire to awe the sailors.

'We terrify them,' said Carnelian. Too much,' said Jaspar.

'We will have to find the way ourselves,' said Vennel.

'Come, my Lords,' Aurum said, 'perhaps that light yonder is what we seek.' He launched himself at the sailors blocking the way in that direction and they shuffled from his path.

The Masters followed him towards the pale rectangle. Carnelian was nervous. The sailors were close enough for him to smell them. He held his torch aloft and scrutinized their faces. He could see their blinking terror of him but also a stubborn resistance.

Aurum brought them to a gateway closed with a grille.

He slapped its wood. It shook but held. 'How dare they lock this against us?'

Carnelian turned back. He scanned the mob, feeling them closing in.

Jaspar drew near him. They are so much like animals.'

'And dangerous,' said Carnelian, distrusting every movement.

'What an outlandish suggestion.'

'We shall have to wait until this portcullis is lifted for us,' Suth said to Aurum.

'Wait? Wait for what, my Lord?' Aurum struck the grille with the flat of his hand, clinking his rings against the wood.

Carnelian edged his way to the portcullis, always keeping his eyes on the mob. He glanced through the bars. There was a landing on the other side stippled with the red light that filtered down from above. A flight of shallow steps came up to the landing, continuing up on its other side.

Carnelian turned to see that his father was standing with both torches raised, his mask looking out blindly into the gloom. He was a pillar at the centre of a region of light. Movements could be seen all along its edge. Carnelian wondered if his father perceived the threat.

The rapid striking sound of Aurum's rings broke out again as he rattled the gate with his blows. Light welled up on the other side of the grille, accompanied by footfalls. Carnelian peered through and saw some small dark men lit by the lanterns they were carrying. One came up, cautiously, holding his lantern before him. Its light rayed through the grille and played around the Masters in shafts.

The small man must have seen their masks. 'Masters!' he cried, crumpling to the floor.

Most of his companions joined him though one ran off down the stairway crying out, The Masters. The Masters.'

'Open this gate!' boomed Aurum.

These creatures are so craven,' said Jaspar.

Carnelian's unease ignited to anger. 'Who makes them so?'

There was some commotion on the landing, a rattle of machinery. One of the men came up towards the portcullis, touched it as if it might be hot, then pushed against it and it slid up smoothly.

Aurum ducked under it before it was fully open. Carnelian followed with the others onto the landing. The men were scurrying down the stairway, leaving their lanterns behind them on the floor.

Something was coming up towards them like a flood. Carnelian moved to the landing's edge. The stairway below was filling from wall to wall with men and a dazzle of lanterns. Amidst the dull eddying of leather jerkins several glinting apparitions floated up much taller than the rest.

Carnelian drew back and took his place beside the other Masters. With a clatter and the odour of men, the mass of soldiery spilled onto the landing.

While the soldiers clunked into the prostration the apparitions kept coming at them. Their bronze carapaces had an insect mottle. Ridged plates of samite were underneath. Each wore an elaborate horned helm into which was wedged a Master's mask. Carnelian was amazed when they all sank down upon one knee.

'Great Ones, I do not know how came about this affront to your blood,' protested their leader. His helm turned its four-horned mass and Carnelian had the feeling that he and the others were being counted. Their obeisance, the mode of address, suggested that these Masters were of the Lesser Chosen. The leader spoke again. 'When your vessel was sighted I commanded this tower be made ready to welcome your return. Imagine my dismay when we reached her berth to find you already gone. This is-'

'An outrage?' suggested Jaspar.

Aurum stepped in front of the kneeling Masters. In his stained cloak he seemed a pillar of mud being worshipped by bronze men.

The injury is forgotten, Lord Legate. We desire to take counsel with you that we might leave as swiftly as we have come.'

'You are kind to condescend, Great Lord, but still-' 'Believe me, there is no ill feeling. Dispense with this speech that we might repair to the privacy of your halls.'

Aurum swept round and billowed up the stairway like a cloud of smoke.

Halfway up the stairs to the window that lit the cave of his hall, the Legate turned off onto a platform. Carnelian stopped where he was and looked back down the avalanche of steps. The door they had entered through was remote. All around him giants in the walls pushed out through veiling rock. Their vague faces frowned into the airy spaces above his head. He was beneath their notice. What was more oppressive still was that they were but the front rank of a crowd that faded up in tiers to a ceiling dripping with stalactites.

Carnelian had to squint to look up the steps to where his father and the other Masters were still climbing towards the window. Against that slab of burning sky they were drawn as quivering charcoal strokes. Bronze urns taller than men squatted up the edges of the stairway. Platforms recessed here and there into the steps. The Legate stood on the nearest one of these. Smaller creatures perched around him were taking his helm apart one gleaming piece at a time. Carnelian watched as each was laid carefully on its stand. When the Legate's head was naked save for his mask, he dismissed his servants. Watching them fan out across the steps as they went down, Carnelian saw a figure coming slowly up through them. Though it wore a mask, it did not have the appearance of a Master. The mask's silver snared a curve of light so that it seemed to be smiling.

A swelling of attar of lilies warned Carnelian that the Legate was there beside him.

'Great One, shall we join the others?'

Carnelian stared at the Legate's tiny head. He wondered if this was a condition peculiar to the Lesser Chosen until he realized it was an illusion caused by the contrast with the massive armour. He remembered to jerk a nod and side by side they began to climb, ahead of the silver mask.

The window widened till Carnelian could not see its edges and felt that he was climbing into the heavens. He stumbled when his foot tried to find a final step. Shapes crowding the platform moved and Carnelian assumed from their size that they were the other Masters. He moved to one side of them and turning his back on the window, hoping to lose his near-blindness.

He watched the Legate move aside to reveal the creature standing behind him on the last step. He had forgotten about it. Its mask was reflecting a fragment of the ochre sky. It made the prostration and when it rose Carnelian saw that it had unmasked to reveal a yellow marumaga face, spotted and striped all over with the dots and bars of numbers. The man's eyes were like glass. He lifted a hand with fingers splayed. Four fingers, the centre one removed so that the hand naturally formed the sign of the horns.

'Seraphim,' he said.

There was a swish of cloth. The Masters around him were making the sign. Self-consciously, Carnelian followed them.

The Legate came to stand beside the throne that piled up from the centre of the platform. 'Great Ones, I had begun to fear your blood mingled with the winter sea.'

'Burning blood is not so easily quenched,' Vennel said severely.

The Legate made a sign of apology. 'I meant no offence, Great One.'

Vennel's mask turned away.

The Legate watched it, his hand flattening. He looked round at the other Lords. There are more of the Great Ones than there were.'

Carnelian saw his father move forward. 'I am Suth, returning to the Three Lands.'

The Legate made an uncertain bow. They have yearned for your return, Great Lord.'

'Before we conclave, Lord Legate, I should tell you that it became necessary to destroy some of the crew of your baran.'

The Legate shrugged.

The captain too was slain.'

Carnelian looked at his father, thinking that he had made an error. Then he recalled the captain's looks of horror and that the man had seen his naked face, and his hands glued together as if they were still covered with blood.

The Legate lifted his hand, So be it. 'Captains are more difficult to replace… the training, you see, Great Lord?

But perhaps the Great Ones might allow me to turn to more important matters. I have here an epistle come from Osrakum that has been in my hand for nigh on twenty days.'

'I had expected this,' said Aurum.

The Legate held out a long folded parchment bearing a square seal larger than his fist.

Aurum began to move forward with his hand outstretched but Suth lifted his own hand on which something blinked red. Aurum nodded and retreated. Suth took the letter from the Legate's hand. He angled it to examine the seal in the light, then snapped it open. He unfolded the first panel, read it, then moved on to the second. Carnelian could see there were many panels and he caught glimpses of the glyphs that were pressed like butterflies between the pages. He wearied of waiting. The other Masters were statues. The only movement came from the yellow man who had still not come fully up onto the platform. Carnelian peered at his costume. He realized that it was not black as he had thought, but a thick purple whirling brocade eyed here and there with bone buttons. There were spirals in the precious purple samite, the spirals of ammonite shells. From his belt hung several strings of many-coloured beads. Carnelian regarded the yellow man with renewed interest, wondering if this could be one of the Wise.

'Quaestor?'

'Seraph,' answered the yellow man.

Carnelian turned. His father was holding up his hand. A bloody eye wounded his palm: a ruby thrusting down from a ring he wore on his middle finger.

'I who am He-who-goes-before make declaration that this is an epistle that concerns a proceeding of the Clave.'

The quaestor's eyes fixed bird-like on the ruby.

'I invoke the Privilege of the Three Powers.'

The quaestor frowned, but resumed his silver mask and, bowing almost to the floor, turned and disappeared down the stairway.

The Masters began to unmask and Carnelian followed their example. He was surprised that the Legate's face had the same luminous beauty as the other Masters. He could easily have passed for one of the Great.

Suth held up the letter. This contains matter pertinent to our mission, my Lords.' He turned to the Legate. 'Lord Legate, the Great require your assistance. The God Emperor lies dying, and-'

Vennel gaped at Suth. 'Have you taken leave of your senses, my Lord?'

Suth turned towards him and wrinkled his brow.

'Have you forgotten, Lord Suth, that it is utterly forbidden by Law to speak of this to any outside Osrakum?'

Suth looked almost amused for a moment. 'It is you, my Lord, who forget. Am I not become He-who-goes-before? When I speak, the voice may be mine but my words are the Clave's. Hear them now when I say that it would be foolish to underestimate the Legate. Did he not himself witness you coming down to the sea? What I have revealed, the Legate already knew.'

Carnelian watched his father lock eyes with the Legate. His father waited for the startled man to give a slight nod before returning his gaze to Vennel.

'Is it not more prudent, my Lord, that we should take him into our confidence than that we should make vain denial? My presence alone would serve to confirm his conjectures.' Suth looked at the Legate, who now hid behind a hand shaping the sign for grief. 'My Lord, you have the confidence of the Clave, and it shall owe you blood debt for your silence and for any aid that you might be called upon to give us. Rest assured that this in no way compromises your service to the House of the Masks.'

'Even He-who-goes-before must obey the Law,' said Vennel.

Suth did not turn. 'Lord Vennel, the Law's intention was to avoid disturbance in the Commonwealth.'

'And to avoid the Legates being tempted to use their legions against the Three Powers.'

Carnelian, who had always feared the look his father's face now wore, watched it wither Vennel.

'Does my Lord fear that my Lord Legate would sail his barans against Osrakum?'

Vennel's face deadened as he retired somewhere behind its icy surface. Carnelian fought his lips' desire to smile.

His father lifted the letter again. The Wise have made the Clave send this to warn us that a rumour is abroad.'

Aurum stepped forward. 'A rumour?'

'It has been noted that several Lords of the Great have gone down to the sea. It is said that they seek the return of the Ruling Lord of House Suth. Further, it is said that this Lord is being recalled to oversee the sacred election. The Wise command that we do all we can to avoid giving credence to this dangerous rumour.'

Vennel gave a snort to which Carnelian could see only the Legate pay any attention.

'It should come as no surprise,' said Jaspar. 'Even though we came here with no banners the faces of our slaves proclaimed who we were. Even the mind of a barbarian would surmise that three Lords of the Great would not come out of Osrakum and down to the sea on trivial errand. Many of the Lesser Chosen know that the Ruling Lord Suth had gone beyond the sea. Taken together, these would form a singular coincidence.'

Then we cannot return upon the leftway,' said Aurum.

Carnelian watched the Legate's pale eyes linger on Jaspar before passing raven-sharp to his father's face.

Vermel looked incredulous. ‘Surely you do not suggest, my Lord, that we forgo the leftway to travel on the road?'

Jaspar pretended to be intent on adjusting his blood-ring. 'Without banners to open up a way through the road's throng there certainly will be no making haste.'

'Besides, how could we hope to hide ourselves?' said Vermel.

Aurum threw up his hands. 'What else would you have us do, my Lords? Should we instead defy the Wise and imperil the Commonwealth?'

Carnelian watched the Legate turn his ivory head to look out through the window. The ochre sky looked painted. The sun's brass still crowned the towers of the town and ran a burning band round the edge of the further cliff.

The Legate turned back. 'Perhaps the Great Ones might allow me to lend them my banners.'

'You presume too much, Legate,' said Vennel. 'You dare suggest that a Ruling Lord of the Great should so demean his blood as to use the banners of one of the Lesser Chosen?'

Aurum fixed Vennel with a baleful eye. This is no time for blood pride, my Lord. Have I to remind you once more of what is at stake? Pomp will be fatal to our mission: the lack of it, to our speed. If we take the leftway as ourselves all the world will soon know what transpires in Osrakum. Only under the banners of another might we hope to pass unnoticed.'

'If the Great Ones might allow me to interject…?' said the Legate, making vague gestures of apology. Suth asked for his words with his hand.

'I intended to lend the Great Ones the banners of my state.'

'And your cyphers?' asked Suth.

'Indeed, Great Lord, those would be essential. The Great Ones would be concealed if they were carried in palanquins. Then they could use the leftway. My duties oftentimes take me inland into the heart of the Naralan, as far as the city of Maga-Naralante, so such a party would excite little notice or question. Beyond Maga-Naralante' – he lowered his head – 'matters might be more difficult.'

Suth nodded and looked at the other Masters. 'I find this idea to have merit.'

Vermel's face was like freshly fallen snow. 'Will My-Lord-who-goes-before accept the responsibility for such an action before the Wise?'

'He will,' said Suth.

'Very well. I shall bow to your will expressed. Now I shall retire. My Lords.' He gave a curt bow, slipped his mask elegandy over his face, then turned to go down the steps. Carnelian watched him sink into the platform's edge like a ship into the horizon.

The Legate moved quickly to the top of the stairs and called after Vennel, 'Any slave you find beyond the door, Great One, will be able to guide you to your chambers.'

'You should go too, Carnelian,' said Suth, 'to make sure the household is set in order for my coming.'

Carnelian stood looking at him, resenting the dismissal, but he could think of no way to defy it.

'As my Lord commands,' he said and put on his mask.

From the platform's brink the steps looked perilously steep. He gazed out across the cavernous space. The lanterns on the floor were undulating bands of light over the walls. He could see the raised walkways that led to the door, and the audience pits on either side. He began descending.

When he reached the foot of the stairway he looked back up but he could see nothing of the Masters, only the window's glow. The murmur of their talk was like the rumble of a distant storm.

Up ahead, Vennel was passing under one of the tower lanterns. Sections of its shaft moved round, turning its rays like spokes. Carnelian began to follow him along the walkway on the journey to the door.

In token of his deafening, the slave's ears had been shorn off. The Legate's cypher, a sheaf of reeds, had been cut into the man's face and traditional tattoo-blue had been used to fill the scar channels. He had been loitering with others beyond the door. Carnelian had to show him the chameleon glyphs on the lining of his sleeve to indicate where he wanted to go. The slave's eyes flickered in the swathe of blue stain as they followed Carnelian's hand-speech. He must have understood for he lit a lantern and, cringing, beckoned Carnelian to follow him into the darkness.

Carnelian followed the small figure through a bewildering series of chambers whose frescoed walls gleamed faintly in the dark. After much walking they came to a hall into which fell shafts of red light regularly spaced off into the distance. Along the left-hand wall Carnelian could just see the archways staring blindly with their Lordly warding eyes. Within the nearest archway was a stone door, bronze-riveted, with niches empty on either side, presumably for guardsmen.

Accompanied by echoes, they walked past several doors until they came to one where the crescents of Vennel's banners told of his presence somewhere beyond.

Some men came out from the niches with their sickles. The cypher gashed across their faces made them seem in awful mirth but their real mouths gave a different impression. Carnelian rushed by, even as they began prostrations, relieved to see his own House colours further down the hall.

'Master,' came a cry of relief from up ahead. Then figures came rushing at him, dappled red, their faces becoming familiar in the light of the slave's lantern. His men surrounded him, bobbing, touching the hem of his cloak. They spoke all at once and grinned and frowned alternately.

'Be quiet,' said Carnelian. 'Come on, quieten down. Do you want to embarrass me?'

The life went right out of them. They became so still, it alarmed him. The Legate's slave was gaping slack-eyed. He dismissed him before turning to his men. 'Don't worry, I'm not angry.' Their shoulders had a subservient hunching he did not like. 'Let's get indoors.'