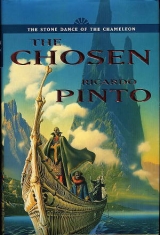

Текст книги "The Chosen"

Автор книги: Ricardo Pinto

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 13 (всего у книги 38 страниц)

'No?' parroted Vennel.

Carnelian could feel all the Masters looking at him. The anger in his father's eyes only served to spur him on. 'Surely it is unseemly that a Ruling Lord should share with anyone?'

Jaspar looked surprised. 'You suggest, my Lord, that you and I share a tent?'

The boy has a point,' said Vennel, acquiring a predatory leer.

Jaspar looked briefly exasperated, then shrugged. 'So be it.'

Such a swift victory made Carnelian uneasy. He looked to his father but he averted his gaze. Aurum's eyes were bright with malice. Carnelian knew he had made this happen and now he would have to see it through. He put on his ranga and his mask, rose, and left the enclosure.

Fire spangled the darkness. The smell of men and beasts mixed with the smoke of meat charring. The rising falling murmur of voices was pierced by flutes, rhythmed by tambours.

Two of the Marula had followed Carnelian to the edge of the knoll. They moved when he moved as if they were his shadows. Carnelian heard a sound behind him and turned. Against the faint light from the Masters' enclosure, a bar of blacker night was drifting towards him flanked by the shapes of more Marula.

'Night is best to brood in, cousin.' It was Jaspar.

Further up the slope the Marula had made a fire and were cooking something of their own.

Their food smells better than ours,' said Carnelian.

'But then of course it is unclean,' Jaspar said, sounding regretful.

Carnelian turned to look at him, a hole cut into the starry sky. 'From whom do we hide, Jaspar?'

'We Chosen hide from everyone, Carnelian, out of care, lest the radiance of our faces blast them to ash.'

'It is the Empress Ykoriana who threatens us, is it not?'

'Lower your voice,' hissed Jaspar. His silhouette consumed more stars and gave birth to others as he moved away. Carnelian heard him muttering commands. The Marula melted away and Jaspar returned. Carnelian felt the gold face sizing him up. 'It is unthinkable,' it said at last.

'Aurum and my father are thinking it, my Lord.' 'It is this Lesser Chosen plot they fear.' Tell me, Jaspar, are the Marula rare in the Commonwealth?' 'What does this-?' 'Humour me.'

They pay us no flesh tithe and only a handful of them enlist as auxiliaries in the legions.'

Then I would suggest that the Ruling Lord Aurum always intended us to return using them as our disguise.' Carnelian could not conceal the smugness in his voice.

'I do not quite follow…'

'Does it seem likely to you, Jaspar, that the Legate would just happen to have more than a dozen of these rare creatures in his auxiliaries?'

'And so…?' said Jaspar.

'And so, either Aurum brought them with him or he had the Legate obtain them. Either possibility makes it certain that the arrangements were made before you all set off across the sea. This suggests that Aurum knew my father would return with him.'

'It is well reasoned.' Jaspar's mask nodded. 'Well reasoned,' he said, his voice lower, as if he were speaking to himself. His mask became very still. 'Why then was Aurum so despondent on the journey out?'

Carnelian deflated. The implication was that the influence Aurum had over his father he had not brought with him. If that were true then he must have found it on the island. Carnelian worried that Jaspar was moving towards the same conclusion and spoke quickly to ruffle the surface of his thoughts.

'By the same reasoning, it cannot be the Lesser Chosen that we hide from. Whatever was written in the letter, it could not be that.'

Jaspar said nothing. Carnelian became disconcerted by the Master's mask floating its dead face in the night. The Marula, my Lord, were already waiting for us.'

Jaspar gave a slow nod. 'Let us say, cousin, that you are right and we are hiding from the Empress, what then?'

'Why are we hiding?'

'Spinning pure conjecture, it could be that she intends to stop your father getting to Osrakum in time to influence the election.'

'How could she do that?'

'She could set assassins searching for him along this road.'

Carnelian went cold with fear for his father. 'She could not… the Blood Convention…'

‘She has already murdered her own daughter.' 'Her daughter?' 'Flama Ykoria.' 'Why…?'

'Ykoriana was the first woman for generations to be born blood-rank four.'

Carnelian almost gasped as he calculated it. 'Her ring casts eight thousand votes. Nearly half as much as all the Great together.'

Jaspar nodded. Through her, Flama Ykoria inherited the same rank. Now, Ykoriana alone enjoys this distinction.'

Carnelian was aghast. 'But even she must fear the Law.'

Jaspar laughed without humour. 'She had already long before suffered all the punishments the Law can inflict on Chosen women: the purdah imprisonment, blinding.'

Carnelian shuddered. 'But not death?'

'We do not slay our women, they are too precious to us.'

Carnelian realized Jaspar was not being ironic. 'What other crime did she commit?'

Jaspar shrugged. 'Some matter internal to the House of the Masks. That is in the past. It is the election that concerns her now.'

'How will victory assuage her bitterness?'

'Nephron is his father's son, Molochite his mother's: a weak prince, a wallower in rare vices. She would wed him, encourage his corruption, then rule unfettered from behind his throne. Of course, if your father were to ensure Nephron's victory…'

'My father?'

Then he would enjoy high favour at the new Gods' side and, should he choose, could wield oppressive power over others of us of the Great.'

'My father would never abuse such trust.'

'He might not, but what if he became an instrument in another's hand? Aurum's, for example?'

'Aurum?'

'You must have noticed, Carnelian, what influence he has over your father?'

Carnelian felt the sweat soaking the bandages on his back. 'I… I really have no idea what you mean, my Lord.'

'Are you certain that you have not, cousin?'

'Absolutely certain.'

'Well then.' Jaspar's mask was a dark mirror. 'We have talked enough, cousin. One would not deprive you of much-needed sleep. The days that follow promise to be wearisome, neh?'

Jaspar turned and walked back up the slope. As Carnelian watched him fade away, his heart seemed to be shaking its way out of his body. A scent of menace lingered on the night air. He told himself that really nothing much had happened. It amused his cousin Jaspar to frighten him a little, that was all.

When Carnelian was calmer he began to climb the knoll. The Marula squatting in the dark like boulders stood up silently as he passed and followed him.

Mattresses thick enough to satisfy the commands of the Law had been rolled out to form a floor in the tent. The air was weighed with incense. Carnelian jerked a nod at Jaspar. He frowned when he saw Tain prostrate with another gangly boy beside him. His brother looked up and twitched a smile.

'What a relief it would be to remove these accursed wrappings,' said Jaspar, speaking from behind him.

Carnelian could feel his own bandages embracing him like clammy arms.

'One fears we will have to stew in them until we reach Osrakum.'

Carnelian gave the boys leave to rise. He registered the look of horror on Tain's face and could make no sense of it. The other boy slipped past him with hands held out. 'Let your slave help you, Master,' he said in a thin voice.

In increasing confusion, Carnelian watched Tain clasp trembling hands over his face. Carnelian turned and saw the other boy's small hands reverently coping with the weight of Jaspar's mask as it was handed down.

'My slave is not as pretty as yours, cousin, but he is a wonder with a brush,' Jaspar was saying.

Carnelian felt sudden nausea as he stared at the Master's naked face. 'You have destroyed my brother.'

Jaspar started back and put on an expression of childlike innocence. 'Cousin? Aaah, you are being droll.'

'You removed your mask.'

'Indeed. Did you think I would sleep in it?'

'But the Law… he will have to be punished.'

'He will have to be blinded.'

'You did it deliberately?' Carnelian put his hand to his head. 'I can't believe it,' he said in Vulgate.

'All the slaves we brought with us will be blinded. Did you really think, Carnelian, that the Great would choose to suffer inconvenience merely to save the eyes of a handful of slaves?' He laughed. 'It is too grotesque.'

Carnelian turned back to Tain. His brother's hands hung limp at his side. He would not lift his eyes.

'One can see no reason for so much distress. What is this pretty creature to you, cousin?' Jaspar gave a knowing smile. 'He will still be able to perform for you.'

'He is my brother!' Carnelian said, aghast.

That is a ridiculous word to use of one whose blood runs dull and cold.' Jaspar reached down to his slave's hand and lifted it. The boy could have been a rag doll. Jaspar opened the boy's hand. 'I might as well start claiming this one to be my nephew, or some such.'

A green tattoo on the palm proved the boy had been fathered by a Master. Jaspar let the arm flop down.

The procedure can be made painless. Besides, you can give him beautiful new eyes of stone. Turquoise would match his colouring. Give him sapphires if you wish to pamper him.'

Carnelian gaped at Jaspar, then dug his chin into his chest and held his stomach. He dared not look round at Tain.

'Do not be cruel, cousin. Think on my loss,' said Jaspar.

Carnelian looked up.

'Yours might at least preserve some of his uses while mine…' Jaspar took his slave's chin in a gloved hand, lifted it. The boy's enormous dark, bruise-lidded eyes closed and trembled. 'Without his eyes, this one will be of very little use.' He pouted his lips, lapsed into Vulgate. 'Isn't that so, little one?' The boy produced a tearful grimace that attempted to be a smile. Jaspar released the slave's chin and turned to Carnelian. 'Feel at liberty to remove your mask, and then we shall be equally responsible for the damage of each other's property.'

Carnelian shook his head slowly, seeing nothing. Everything was drenched with decay. His father must have expected this would happen and had done nothing to stop it.

Jaspar was all joviality. 'You really will have to forget these peculiar sensibilities, Carnelian. They are so unbecoming in one of the Chosen.'

Only in the dark did Carnelian remove his mask. Then he lay down, rubbing the edges of his face where the mask had dug in. He clasped his left hand over his blood-ring, the sign of his manhood. It was not a charm. He felt like a lonely child. Tain was somewhere outside. Jaspar had insisted it was not fitting that a Lord should sleep in the same place as another's slave. Carnelian had said nothing to Tain. What comfort could he have given him even if Jaspar had not been there? His brother could not have understood the Quya, but he knew well enough what punishment would be his for looking on a Master's face.

Carnelian could hear Jasper's slow breathing. He wondered why he felt no anger towards him. It was a terrible betrayal to feel no anger. With a peculiar detachment he considered the conversation he had had with the Master. He knew now that Jaspar's motives for talking to him had not been any attempt at friendship. Jaspar was no different from the other Masters. In that, at least, his father had been right.

Outside a voice was singing. Its sad sound failed to touch Carnelian. Everything seemed to be shut outside him. He wanted to die. What point was there to a life in which one felt nothing? His fingers found the mattress edge. They dangled over. Then, daring sacrilege, they pushed down to touch the unhallowed, corrupted earth. Carnelian expected something, a shock, a sting but there was nothing, nothing but his fingers stirring dust.

Carnelian was woken by aquar song welcoming the dawn. He sat up. He could hear the murmur of the camp. His body ached all over. Jaspar was gone. Squatting in a corner, Tain was staring at the ground. As Carnelian stood up, his brother came over to help him dress. They adjusted Carnelian's riding cloak avoiding each other's eyes. Carnelian felt that if he were to stretch out his hand he would stub his fingers on the wall that had risen between them.

'I bet you thought those four-horned monsters on the road were dragons, eh, Tain?' He could hear the flat emptiness of his words.

His brother shrugged, bit his lip and continued to adjust the riding cloak.

Carnelian drooped as if his bones had been removed. He put his hand on his brother's chest. 'How are you feeling, Tain?'

His brother looked up, furious. 'How do you think?'

Carnelian looked at those bright angry eyes and imagined them replaced with dead stone. 'It's not my fault,' he shouted. 'It's not.' The last word tailed off. He could see that Tain was close to tears.

'I'm sorry, Tain,' he said gently. His legs felt too weak to hold him up. Reassurances were on his tongue but he remembered Crail and swallowed them. He reached out to touch Tain, but his brother drew away.

'A Master might see us.'

Tain held out his mask. Carnelian took it, put it on, drew the cowl over his head then walked out into the morning.

A dewy fragrance overlaid the smoky stink. Clinks and voices sounded sharp, seeming nearer than they were. The throng was fidgeting into motion.

Soon Carnelian was mounted with the other Masters and filing back through the camp. Tain sitting on the baggage found a smile for him. It hurt Carnelian as much as if his brother had thrown a stone. Men levered wagon wheels into turning. Pots clacked as they were stowed. Urine dribbled on embers, hissing steam. Laughter and the shrilling of babies pierced the swelling hubbub.

The Marula jogged their aquar onto the road. Mist hid the animals' bird feet. Another of the way-forts lay a little distance back along the road with its sinister fence of punishment posts. Carnelian looked out over the stopping place. Its brown flood of travellers was leaching towards them. A diamond-bright gash had torn between earth and sky. Chattering clouds of starlings flashed down from the trees. Then he turned as he felt the Masters moving and they were off: amidst the trundling chariots, the creaking axles, the chatter of the women, they were off into the south, to where the Naralan met the Guarded Land.

For days they rode the road's relentless rhythm, pounding into endless dusty distance. Night brought hri cake, incense, weary hope. Carnelian looked across a chasm at his father. The other Masters were quick to anger. The Marula cordon beat away the hucksters and the curious. Tain's eyes dulled as if they were already stone. Carnelian hid in his cowl, blood pulsing in his head. The thud and thump of huimur feet. Sandals scuffing, scraping. Wheel rims always rising always falling. Litters rocking. People dragging squalling infants. Hand-carts hard pushed to keep in chariot shadow. Swaying horned saurian heads. To kill time, people quarrelled over trifles. Heat. Unbearable heat desiccating everything to chalk. Out from the haze far behind them the road's procession bubbled. Up ahead, it simmered away to nothing. Carnelian sagged dozing, sometimes sucking furtive gulps of water in the shadow of his cowl, brooding, licking without caring the stone of salt that had been pressed on him as protection from sun madness. His legs, his back, his neck nagged aching. His head nodded bobbing, keeping time with the rhythm of the road.

Tain was wasting as thin as Jaspar's boy. Carnelian had tried to make him eat, to comfort him. All this had to be done in snatches, for at night Jaspar was always there and in the day Tain was lost amongst the baggage.

Carnelian wore a face of patience over his anguish. He kept Tain away from the tent when Jaspar was there, hoping that the sin might be forgotten. Sometimes, when Carnelian had to undress himself, Jaspar would give him his indulgent idol smile. It was then that Carnelian's self-control wore thinnest.

Jaspar persisted in finding fault with his own slave. It had been agreed that there were to be no punishments on the road and so instead the Master amused himself by describing to the boy those that were waiting for him in Osrakum. Carnelian turned from the slave's sweaty trembling, bit his tongue, struggled for deafness. Their tent stank of the boy's fear.

Pulsing cicadas, buzzing flies, the sounds of the road, all were muffled by the lazy heat. Even in the cedar's shade the air was stifling, but Carnelian was thankful for the tree. The throng shimmered along the road. Away towards the melting horizon the towers of Maga-Naralante danced their dark flames. The city was like a mirage. Vennel pointed towards it.

'My Lords, there we could find discreet comfort: a welcome respite from the road. We would resume our journey refreshed.'

'Sometimes legionaries collect the tolls,' said Aurum. They might see through our disguise.'

The markets, the narrow streets,' said Suth, 'all would be inimical to secrecy.'

Vennel muttered his discontent. His aquar echoed him with a rumble in its throat.

The shadow-dapple fused each Master and aquar into a single fantastical creature. Carnelian chewed his lip. Even though their saddle-chairs were almost touching, his father was beyond his reach.

'However much we may share your desires, Vennel, the risk must be avoided,' said Suth.

Carnelian fixed his eyes back on the road. He was always on the lookout for Ykoriana's assassins.

'Again I am overruled,' said Vennel, 'and again I think the diversion will prove the more delaying choice.'

'Does my Lord wish to have the matter put to the vote?' said Jaspar.

Vennel turned to him. 'Would there be any point?'

'I would vote with you, Vennel. I have a notion to spend a night in something like comfort.' He turned to Suth. 'Whatever the risk.'

'So be it,' Aurum said sharply. 'My ring I set against yours, Jaspar.'

'And mine against Lord Vermel's,' said Suth.

Jaspar looked at Carnelian. 'It seems then that it is you, cousin, who is to decide the matter.'

Even muffled by his cowl and mask, Carnelian could tell the Master was smiling his damned, self-satisfied smile. He surveyed the four Masters in their saddle-chairs. It occurred to him that if he voted with Jaspar it might help the Master forget Tain's sin. There would also be the pleasure of voting against Aurum. The most important consideration, though, was that he would be voting against his father. His father was to be pitied. Every day he showed more clearly the power Aurum had over him.

'Carnelian,' Suth said. 'How shall your ring fall?'

It was the first time that his father had said anything to him for days. Carnelian looked at him, wishing he could see his face.

'Why do you delay?' said Aurum, as if he were talking to a boy.

'I shall vote with my father,' said Carnelian.

'One is not surprised, my Lord,' said Jaspar, 'but a little disappointed. Now that you have come of age one did not think that you would so blindly follow your father's lead.'

Carnelian started at the emphasized word. As they rode back into the crowds, he wondered if there was anything Jaspar would take in exchange for Tain's eyes.

They left the road within sight of Maga-Naralante's black gate. Rolling dust broke over them. Wheels rattled violently as they jolted into the ditches that criss-crossed the track. Foul stenches rose with the flies. Hovels all sticks and wattle leant over into their path. When the air cleared a little Carnelian saw more of this debris sloping up towards the city's mud rampart like a scree. There were too many vehicles squeezing along the track. A chariot snagged a hovel and tore it down. Its wheel collapsed, swerving the chariot into the path of a huimur. Bleating, the monster swung away, crushing into a crowd of travellers. The wagon it pulled tipped over. Bundles rolled into the gutters. Filthy urchins appeared and swarmed the wreck. The traffic built up behind. Annoyance swelled to anger then burst into riot. It was easy for Carnelian to imagine assassins in the crowd. Aurum must have shared his fears for he ordered the Marula to slay a path through the mob. People were cut down screaming. Carnelian stared into a face foaming blood, then he leapt his aquar over the wagon pole and loped off along the track after his father.

Trouble comes often to those who are too cunning,' said Vennel.

'It comes always to those who show no cunning at all,' said Suth.

Aurum had his back to them. The straightest road is not always the fastest.' He had made the Marula put the enclosure up around an ants' nest. He had opened its belly with a knife, dropped in a firebrand and was using another to crisp the ants that sallied out.

'Blood burns brighter than oil,' said Jaspar.

Suth and Vennel both turned on him.

He lifted his hands in apology. 'I thought we were listing proverbs.'

'I fail to see, my Lords, how our objectives were served by what happened today,' said Vennel.

'What happened today is irrelevant,' snapped Suth. Carnelian saw his father looking at him as if he were an apple just out of reach.

'If we remained undiscovered it is due to fortune and not to any skill in planning on your part, my Lords,' said Vennel. 'I would hazard that the commotion and the violence of our escort did little to turn attention away from us.'

'Violence is not uncommon on this road,' said Suth.

'So you say, my Lord, so you say. But I do not think that creatures of the kind we mimic would show such elan for slaughter.'

Carnelian searched his father's eyes. It was as if he were trying to say something to him. Carnelian rose and moved towards him.

Suth immediately stood up and looked down at Vennel. 'My patience with this discussion is at an end, my Lord.'

He put on his mask, hid it with his cowl and left the enclosure.

Vennel looked at the other Masters as if surprised. Jaspar smiled enigmatically. Aurum looked bored as he lit the ants one by one like candle wicks.

On the thirteenth day after they had left the sea Carnelian noticed a darker southern horizon: a crack between earth and sky that could only be the rim of the Guarded Land. Next morning it looked closer, a ribbon of liquid blue dividing the world. That day and for the next two it was lost in the blinding white burning of the Naralan, but the day after that it formed a permanent smudging lilac layer in the haze. It crisped and browned, bubbling up so that when they camped that night it had solidified into a heavy banding of the darkening sky.

The eighteenth day dawned. That day the cliffs of the Guarded Land wavered up from the simmering plains as a dark forbidding wall.

The road climbed into a cutting in the cliff. Its gradient was so gentle that when it reached its first turn and doubled back, its corbelled edge was obscured by the flags of the chariots passing beneath. Its scar zigzagged up the rock seemingly all the way to the clouds.

The road climbs to the very top?' Carnelian asked, incredulous.

'More accurately it descends it,' Vennel replied.

'We had it built down from the Guarded Land so that we might reach the sea,' said Jaspar.

The city of Nothnaralan waits for us up there,' said Jaspar.

Carnelian pushed his head back against his saddle-chair to try to see the sky city. 'With what sorcery was all this wonder wrought?'

'Not sorcery but sartlar,' said Suth.

Carnelian could hardly believe that his father was talking to him. 'It must have cost many lives,' he said, trying to nurse this little spark of intimacy.

'It is said that this hill is the knitted mounding of their bones.'

Carnelian glanced back down the slope that carried the road to the plain. 'So much death.'

The sartlar are a limitless resource.'

The world is as verminous with such creatures as slaves are with lice,' sneered Vennel.

'Are they all enslaved?' asked Carnelian, resenting the Master's intrusion, aiming his question at his father.

Vennel turned his hood towards Carnelian. 'Is that not what their name means?'

'Yet once they were free,' said Suth. 'When our Quyan forefathers scaled this cliff to the land above, they found the sartlar already there and-'

'And domesticated them,' snapped Aurum.

Carnelian could have cursed him. His father would say nothing more.

'Come, my Lords,' the old Master continued. 'We are not at some elegant reception.' His hand lifting caused the Marula to rise up from where they had been huddled round them in a ring. 'It is time that we rejoin the road and begin the ascent. Several days must pass before we reach the land above.'

'One might forgive the creature's sin,' pureed Jaspar.

The words made no impression on Carnelian's mind. He was already exhausted from the climb and still they were only halfway up to the Guarded Land.

'You would of course have to pay me recompense,' said Jaspar in a low voice. 'For such a one to go unpunished…'

Carnelian turned blindly to the cowled figure.

'Do you toy with me, my Lord?' said Jaspar, warming to anger.

'My Lord?'

'What price will you pay to save his eyes?' Jaspar came into hard focus. 'You speak of my brother?' said Carnelian. 'Your slave, my Lord.'

Carnelian frowned. He must not let his fury wake, nor his hope. 'What price would my Lord ask for this act of mercy?' he asked coldly.

Jaspar turned away, gazing out into airy space. 'If I were to forget that the creature had looked upon my face it would be more than an act of mercy, Carnelian.' He turned back. His cowl framed an oval of blackness. There is but one price, cousin.'

Carnelian stared at him as the anger bubbled up in him. 'Well?' he cried, boiling over.

'Hush, Carnelian. We would not want the others to learn of our negotiations, would we? It is a simple boon I desire from you, namely, I would know what hold Aurum has over your father.'

'You would have me betray my own father… for a slave?'

Jaspar chuckled. 'Come now, Carnelian, look how quickly your brother has become your slave.'

'It is unthinkable,' gasped Carnelian.

'Perhaps… and yet I think you would like your brother to keep his bright, animal eyes.'

Carnelian shook his head. 'I cannot do it.'

Jaspar opened his hands. 'Perhaps my Lord will change his mind. Think on it, but do not take too long.

The day the boy sees the outermost gate of Osrakum could well be the last day he sees anything at all.’

Jaspar pulled his cloak round him and hunched before slipping through the screens.

Carnelian watched him go, trying to see through his hatred the slim hope that lay in the offer. Some pennants jiggled like butterflies above the screens. The next push up the road was beginning. Carnelian turned for one last look out across the vast pale wash of the Naralan spread out below, then he left the parapet.

They were climbing into purple sky. The edge of the cliff above was jagged with tottering tenements, streaked green with the filth that ran down their walls. A sewage stench wafted on the torrid air. They walked their aquar up onto the lip of the Guarded Land. The end of the climb at last. The throng fanned out to carpet the level field that had been gouged into the edge of the plateau. It was like half a bowl sunk into the cliff's stone. Its sides merged up into the towered mud ramparts of Nothnaralan, whose dusty sunset-rouged face was drilled with countless windows. The whole smooth curve was unbroken except at one place in the east where stony towers intruded to offer up a pair of doors, bloodied gates upon which the sun embossed the twin faces of the Commonwealth in flaming gold.

Thus does the Commonwealth attempt to close her doors against the night,' said Suth in a melancholy tone.

The road had spread its tapestry all around them. They had managed to reach the eastern edge of the field near the gates. Aurum had not allowed them their enclosure, judging that it would not hide them from the windows in the walls above. The other Masters had all been too weary to protest.

Carnelian looked past the cordon of the Marula, out over the squatting masses, over the clumps of wagons and huimur, to where the city walls had already been claimed by darkness.

'I think I will retire, my Lords,' said Vennel. The shadow in the loop of his cowl scanned them as if he expected some retort. When the Masters said nothing, he rose, hunched as they always did to conceal their height, and shuffled off towards the tents.

Carnelian glanced at his father's inanimate form and turned back to his vigil. He watched the city's shadow creep over the camp, lighting fires as it went. Its blackness washed over him, lapped at the foot of the gates, then scaled them to the very top. The sky gave one last violent blush, then indigoed. With its windows now lit up, Nothnaralan formed a hem to the starry night.

Carnelian struggled to sleep in the clinging myrrhy heat. The bandages were restricting his breathing. Sweat crawled beneath the cloth. His heart would not quieten. Memories of his island home flashed into his mind. Every image had acquired a warm aura. He ached with the longing for friendly faces, familiar smells, a single lungful of cold clean wind that spoke with the voices of the sea. There were other darker visions. Tain eyeless, the empty sockets accusing him. He had made a promise to Ebeny to protect him. The thought of Jaspar's offer caused a rushing in his stomach. Carnelian fixed his mind's eye on the memory of the double-headed gate and felt a sweat of excitement. What wonders lay beyond?

Jaspar groaned in his sleep. Carnelian sat up. The camp was murmuring outside. With slow care he rose. He fumbled for his travelling cloak, found it, gathered it in. He tucked his ranga shoes under his arm, crept to the opening, put the shoes outside, stepped up onto them, covered himself, then pushed his masked face out into the night.

The moon was setting into a smoke-scratched blue darkness in which a hundred campfires flickered. The smells and sounds of beasts and men were gently settling. He looked over to the gate glimmered by moonlight.

He was searching for Tain when he noticed some moving shapes. A coalescing of the night. Lifting up, moving, merging, dropping down, disappearing. He waited. They rose again, came closer. He wondered if they might be Marula. The shapes were too furtive. To see better, Carnelian dared to remove his mask. He turned it sideways so that he could still breathe through the nose-pad. Over its rim he scoured the night. The Marula were still round them like a ring of stones. Again the shadows slid into motion. Again they stopped and vanished. Cold sweat, fear and his eyes searching. He bit his lip, looked round and made his decision. He dropped down from his shoes. Half in crouch, half crawling, he moved forward, touching the earth now and then for balance. He reached one of the Marula and crept into the man's aura of stale sweat. His fingers touched the man's warm skin. As it jerked under his touch, Carnelian hugged the man hard against his chest and stifled a cry with his hand. He pushed his mouth into an ear. 'I'm a Master,' he whispered, and felt the bur of the man's hair and an earring moving against his lip. The Maruli tensed hard as wood. 'Silence. You understand?' The woolly head nodded against his face. Carnelian released him. Saw the yellow eyes. Watched them widen. The man scrunched into a ball against his knees.