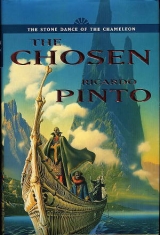

Текст книги "The Chosen"

Автор книги: Ricardo Pinto

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 2 (всего у книги 38 страниц)

Carnelian tried to return the smile.

'Now that the introductions have been made, my Lords, I might suggest that we retire,' said Vennel. He had a woman's voice and his Quya was like singing. 'One must confess to a certain weariness.'

'What resources we have here are at your disposal, my Lords,' Suth said. 'Apartments have been made ready. I hope my Lords will forgive the little comfort we can provide. If we had been advised that you were coming…'

'We have come in haste, my Lord,' said Aurum. There was neither the time nor the opportunity to herald our arrival.'

Jaspar smiled again. 'A little comfort will be rendered great by comparison with our recent accommodation.'

'Shall we then tomorrow meet in formal conclave?' asked Vennel with his woman's voice.

The others lifted their hands in assent.

Till the morrow then.'

Vennel began to move towards the door. Aurum did not move. Vennel turned. 'You are not accompanying us, my Lord?'

'Not immediately. I shall remain here and reminisce with the Lord Suth. Nostalgic nothings can resurrect the past.'

Jaspar raised an eyebrow then dropped it again. Vennel's expression froze for a moment.

Carnelian saw the sag in his father's face. He went up to him. 'You are weary, my Lord.'

His father smiled a bleak smile. 'Perhaps I will find refreshment in reliving the past with the Lord Aurum. Go now, my Lord, and see that our guests are well looked after.'

Carnelian bowed. Aurum was looking at him with gleaming eyes. Carnelian blushed. As he led Jaspar and Vennel to the sea-ivory doors, blinded slaves appeared. Carnelian stared at their puckered eyelids then, copying the others, he held his mask up before his face and a blindman bound it on. As the doors opened, he looked back. His new uncle, Lord Aurum, had stretched a long arm across his father's shoulders like a yoke and was moving him off into the shadows.

THE CONCLAVE

A child can oft more fates decide

Than can a meeting of kings.

(proverb – origin unknown)

He came up from a murky dream, the mist of memory thinning into vague uneasy recollection then fading to nothing. Cold. Cold darkness. Carnelian sensed it was not long till sunrise. The shutters were rattling. Sleet volleyed against them like arrows. Perhaps he had dreamed the visitors with their long black ship. His heart beat hard. He did not know which was worse: that they had come or that they might not have come at all. He put his feet onto the floor, fumbled a blanket round him and walked over to the shutters. When he swung them back, the wind ran iced fingers through his hair. Its kissing snow set him trembling. In the morning twilight the waves swayed their sickening surge. The ship was there in the anchorage, black as a hole.

He did not bother to wake Tain. His brother's breathing was fitful. Carnelian had returned to find him sleeping there on a makeshift bed and had not had the heart to send him back to his own room. In truth, he drew some comfort from having him there. He would just have to do without paint.

He hunted around in the half-light. He found an under-robe and slipped into its icy grip. He threw on more layers until he began to feel warm. His gull-feather cloak went over everything. He walked towards the outer door and stopped. 'Gods' blood,' he hissed. He returned for his mask. He had no intention of running into the visitors but it was safer to be cautious. He hitched the cold thing by its straps to his belt and returned to the door.

He should have expected the guardsmen outside. They eyed his cloak. One of them stepped forward. 'You know you're not supposed to leave your room, Carnie, not till the Master sends for you.'

'If there's anything you want we'll go and fetch it,' piped up another.

'Who told you this?'

'Grane,' said the first.

Carnelian glared at the man, who flinched. For a moment he considered putting on his mask and commanding them to let him pass. Grane's granite face appeared in his mind. It was one thing to play the Master in front of the visitors, quite another to do so in front of his people. He nodded and bit his lip. One of the guardsmen sighed the general relief as Carnelian retreated back through the door.

His hand kneaded the door handle. With the arrival of the visitors his life had changed, and not for the better. His father had warned him of the restrictions of life in Osrakum but Carnelian had never expected these to come to the island. All his life he had heard his father say that life in the Hold was very lax. Still, he burned with questions and would have them answered before the conclave.

He considered his options and made up his mind. He strode back to the window and let in the grey sky.

'What are you doing?' a voice said behind him.

Carnelian turned to look at Tain. He was propped up on one elbow squinting past a hand. 'I'm going to find out what's happening. If you could bear it, Tain, I'd appreciate it if you'd hold the fort till I come back. You know, pretend I'm still here.'

'What…?'

Carnelian was not in the mood for long explanations. He climbed into the window space, braced himself against the wind and looked down at the swelling anger of the sea as it foamed and mouthed the rock below. He mastered his fear and peered just below the sill. The ledge was there, slushy, slick with spume.

There was a tugging at his cloak. 'By the horns,' he heard Tain spluttering, 'are you trying to get yourself killed?'

Carnelian craned round. There're guardsmen at the door and this is the only other way.' 'But you'll kill yourself!'

'Rubbish. We've both done this a hundred times.' 'When we were little, Carnie, and even then, never in winter.'

'Let go, Tain,' Carnelian cried and pulled away.

Tain let go, afraid Carnelian might pull so hard he would lose his balance. Tain knew well enough how obstinate his brother could be. 'Yesterday, when he wasn't going out, he needed to be painted,' Tain grumbled. Today, he's prepared to go out on ledges with naked skin.'

Carnelian ignored his brother, stooped down to remove his shoes and tied them to his belt beside the mask. It was better to feel the ledge. He lowered a foot down to it, ground his heel into the slush and bore the stab of cold that went up his leg. The other foot joined the first. He turned to face into the room and walked his fingers over the stone of the wall outside looking for the once familiar handholds. He had to search a bit. The last time he had done this he had needed to stretch for them, now he actually had to bend his arms. Below him the sea was a beast ravening at the cliff. He edged along. His foot slipped, thumping his heart up through his throat. He made a shuffle to the side, another, one more and he had reached the next window. It would not open. Shoving it, he almost pushed himself out into space. He did it again, with more care. The catch gave way and the shutters snapped into the room. He looked back to his own window. Tain's face was there, sick with fear. Carnelian winked at him then disappeared.

Carnelian slipped into the barracks. He had no wish to run into the Masters or any of their guardsmen. He found a balcony that looked down into the Sword Court. A path had been cleared across it through the snow. The training posts with their wooden arms and heads were buried up to then-waists in drifts and looked like miserable old men. Carnelian smiled. There was nobody about.

He skirted the court, avoiding the main corridors. When he reached the final stairway he could hear voices. He listened for a while. When he was sure they were men of his own tyadra, he went down to the alleyway. Its cobbles had recently been scraped clear but were already smearing with new snow. Two of his men were there. One had a brush and a cake of paint that oozed its indigo over his palm and was dribbling it down his arm. The men looked up and saw him.

'What're you doing?' asked Carnelian.

'Making wards, Master.'

'Don't you "Master" me, Poal.'

The man showed gaps in his teeth as he grinned.

Carnelian looked north towards the Holdgate, then south into the Sword Court. The eaves' icicle jaws clamped a leaden sky. There was no sound, no movement save for fluttering snow flecks. He turned to inspect their work. An eye was already painted on the archway. The run of the paint was making it cry. Below this they were daubing a crude chameleon. The first sign warned against any uninvited intrusion: the second removed the restriction for those belonging to the House Suth.

'Where's this being done, Poal?'

'Everywhere, Carnie.'

'Are the strangers wandering around?'

The man shook his head. 'I've not seen any today.'

'Where's Grane?'

They both shrugged.

'Keal?'

'In the kitchens, I think,' said the other man.

Carnelian thanked them, crossed to a door, opened it and slipped into the warm gloom beyond. Somewhere a door slammed. He felt his way down narrow corridors, met no-one and managed to reach the kitchens unseen.

Pungent smells. A steam of air. Enough smoke to sting his eyes. Fires hissed and danced their gleam across walls panelled with platters of precious brass. Endless clatter, clanging and the scolding of the cooks. Stone slab tables stood on either side of the firepit. The centre of each was jammed with condiment boxes and bottles of sauces. Round them people were chopping with flint cleavers, slicing with obsidian knives. Along one wall were the cisterns with their chipped-lipped spouts where dishes were being scrubbed. Cracked flagged floor, tiled walls.

The whole huge room funnelled up blackening into a chimney.

Carnelian wandered into this world with his customary delight. He almost forgot his reason for being there when he saw they were cooking feast dishes. The storerooms had yielded up their treasures. Dried fish wallowed in pools of marinade. Air-mummified birds were being soaked in red, honeyed oil. A boy was binding their feathers into fans for garnish. There were flint-grey shrimp just drawn from their tanks, still trembling their combs of legs. Fruits like wizened jewels were being sorted into their kinds. The seeds and bark of rare spices were being pounded into pastes with garlic and rounds sliced from the segmented giriju roots, whose gnarled golden fingers had to be handled with leather gloves because their juice burned skin. Carnelian insisted on sniffing everything and the cooks indulged him. One of the older women slapped his hand away when he stole an apple. He made a face at her and she waggled her cleaver at him. Everyone laughed. He bit into the fruit, grimaced at its bitterness, and she told him that it served him right.

He came to the firepit and peered into the pots. Some had green sauces, others yellow. In one a pair of carp swam round in the warming water. He stirred another, fishing for morsels with a ladle, curious to see what might be wandering in the depths.

He reached the pool into which the Hold's spring was pouring its liquid ice. Girls were ranged around its edge, drawing water out with pitchers. He asked for Keal and one of them pointed. He did not see her shy adoration or the way the other girls exchanged meaningful looks. He made for his brother's broad back and slapped it.

Keal spun round cursing. The anger slipped from his face. 'What're you doing here? Grane'll be furious-'

'Grane's always furious. Besides, his bird'll be back in the cage before ever he finds that it's flown.'

The order to keep you there came from the Master himself. You do know that, don't you?'

Keal's eyes were storm-grey. His skin was a pale honey-brown. He was tall enough to reach Carnelian's chest. Of all the children his father had sired upon the household women, Keal was the one who looked most like him. Those eyes, that severe look, were the Master's. Carnelian felt a familiar pang because Keal would never see this for himself. In the household none but the eldest had ever seen his father's face.

'Come on, you'd better get back there anyway,' said Keal.

'Before I do I'd like to know a few things,' said Carnelian. 'First, tell me what happened last night. The warlike preparations-'

'Hush!' Keal grabbed his arm and dragged him off into the intoxicating stink of one of the storerooms, whose walls rustled with dried squid.

Keal looked so serious Carnelian almost laughed.

'I'll tell you what I know but you must keep it to yourself, OK?'

Carnelian nodded.

'I don't know why I'm doing this.'

'Because we're brothers, of course.'

'As well as that. I'm just hoping that you'll make less trouble if your damned curiosity's satisfied.'

'And because you know you're no good at hiding things from me.' Carnelian grinned.

'Do you want to know or not?'

Carnelian made his face serious, then nodded.

'Well listen then. The Master armed us and made us man the Holdgate. I was with him as we watched the Masters coming up the road. I think he was as shocked as the rest of us that they were here.'

'How do you know that?'

Keal shrugged. 'I just do.'

Carnelian let it pass.

'He put me in charge of the Holdgate. He told me that when the Masters demanded entry I was to delay them, tell them that we were waiting for word to come back from him in his hall before we could let them in. He told me that I mustn't on any account open the Holdgate till he sent word. Then he left with Grane and-'

They left you there to face the Masters by yourself… to openly disobey them?'

'Well, it wasn't quite like that. It was their tyadra that actually demanded entry. Mind you, even then it wasn't easy.'

'Go on.'

Keal's eyes blanked. Though the Masters said nothing I could feel their anger rising like the storm. They just loomed in the background. It was terrifying. It was like contradicting the Master himself.'

Carnelian shuddered. 'I can imagine.'

'At last one of the Master's blindmen came. I can't remember all he said, you know how weirdly they speak when they're carrying one of his commands, but the gist of it was…' He stopped and walked to the doorway to make sure there was no-one nearby, then came back. The gist of it was that we were to let them in with all proper respect and to escort them to him, leaving none at the Holdgate. They were to be treated as the Masters they were but… we should think of them as being pirates come to plunder the Hold.'

Carnelian stared at his brother. 'He said that?'

Keal nodded, his eyes big and round. 'Or something very close.' 'Was that it?'

Keal chewed his lip. 'Not quite.' He had lowered his voice. The blindman also said that, at the Master's word, I was to be ready to destroy them.'

'What?' Carnelian was stunned. Even the suggestion of harming a Master seemed blasphemy.

That's what the man said, and he brought the Master's ring to prove it.'

Their eyes locked.

'Is there more?' Carnelian said at last.

'I was to stay at the Holdgate and expect an attack from the ship. If any of them came back through the Hold without their escort they were to be destroyed.'

'And later?'

Things changed. When you came out of his hall with the two Masters, you remember, I took them to the west rooms? That's where they are now… I hope. When I came back Grane was there and the other Master was still inside. The Master came out-'

'Which Master?'

'Our father.' Keal blushed from the use of the word. 'He came out and told us that we could relax our alert a little. He made most of us stand down. He said he wanted us rested and fresh for this morning.'

'And today?'

Today he's told us to paint wards everywhere. Grane was told to protect you and stop you wandering about.' He gave Carnelian the severe look again.

Carnelian patted his shoulder. 'It'll be all right. Tell me about our people. How are they feeling about all this?'

'What do you think, Carnie? They're all dancing for joy.'

'What're they afraid of?'

The Masters, of course, and do you blame them? They're a scary bunch. People know something's up but they don't know what.'

Carnelian nodded grimly. 'I suppose I feel a bit like that myself.' He saw his brother tauten and reached out to touch him. 'We'll be OK. My… our father won't let them harm us.'

'But, Carnie, they're taking so much, so much of everything.'

Carnelian remembered the kitchen. 'You mean food?'

That and other things. Their demands just don't stop. We've already started digging into our reserves. If they stay even a few days they'll eat into our stores, and you know as well as I do that there's nowhere to get more before the ships come.'

Carnelian nodded. He knew how carefully they had always had to husband their resources, especially in winter. He was still brooding as they walked back into the kitchen.

There you are,' a voice cried.

Carnelian's heart sank. His Aunt Brin was sweeping towards them across the kitchen.

'You do know it was the Master himself who ordered you to stay in your room?' said Brin as she reached him. She turned on Keal. 'And I would've thought you at least would show more sense.'

Keal flushed. Brin was not only the Master's sister but she also had control of all the household except for the men of the tyadra. That did not stop them fearing her tongue. The kitchen clatter faded away as people turned to stare.

Carnelian grew angry. 'Don't you dare take this out on him, Brin. I was the one who forced him to talk to me. He was all for getting me back to my room.'

Brin grunted, scrunched up her face. The legs of her chameleon tattoo disappeared into the creases in her cheeks. 'Look at the way you're dressed, Carnelian. Do you have any idea at all what might happen if any of the strangers were to see your face?'

Carnelian drew his cloak back to reveal the mask hanging at his hip.

'It's a lot of use there under your cloak. Besides, the Master's command is the Master's command. Go back to your room.' She turned to Keal. 'And you, since you're so easily forced away from your tasks, maybe you'd better give up what you're doing and escort him. Make sure he gets where he's going, then go and tell Grane that I don't want to see you or any of his other boneheads in my kitchen for the rest of the day.'

Keal hung his head. 'Yes, Brin.'

Carnelian lost his anger. He knew Brin was right and already had enough to do without having to run around looking out for him.

'What are you lot gawping at?' bellowed Keal, glowering.

Brin made just enough room to let them pass. The clatter resumed as they fled her disapproval.

For most of the morning Carnelian fretted in his room. Tain went out several times but each time came back with nothing new about the visitors. They both became sullen, infected with the general foreboding.

When the summons came at last, Tain dressed him in the grey robe and handed him the circlet, the Great-Rings. When Carnelian was ready an escort came for him from Grane, gleaming in their polished leather cuirasses, their hair freshly oiled, their blades honed and waxed. Carnelian said he was proud of them and they all beamed. He marched between them through the Hold. Every door, every arch Carnelian saw was warded with a freshly painted eye and the Suth chameleon. Only the three doors that stood on the alleyway's final stretch were any different. They too had the warding eye but below it the cypher of the Master who had taken possession of the halls that lay beyond: Vennel’s disc and crescent evening star, Jaspar's dragonfly, the horned-ring staff of the Lord Aurum.

In the past, Carnelian with the other children had sneaked into those dismal halls with their views of the anchorage and the bay. All his life they had been a haunted, musty hinterland of the Hold. He tried to imagine them transformed into mysterious luxury by the households the visitors had brought with them, and failed. It was far easier to imagine the Masters lying in dusty state like kings in their tombs.

Carnelian was relieved to find his father alone. He formed a pillar of shadow against a rectangle of glowering sky. Carnelian crossed the hall towards the window. A carpet of embers glowed in the round hearth. The nearer he drew to his father, the louder spoke the wind and sea.

'I am come, my Lord, at your command.'

The apparition turned. The face looking down at him was like a lamp. The eyes seemed of a piece with the sky. 'I wished to speak to you before the conclave.' His father turned back to view the sea, a vast slate-green plain stretching off into the south. 'It is likely that we shall be returning to Osrakum.'

That name reverberated through Carnelian like a bell. Visions flashed through his mind with the quickening of his heart. He saw a memory from childhood of his father cupping his small hands in one of his. The little bowl of fingers was Osrakum: a crater hidden within a mountain wall. Circling the inner edge, his father's finger had let him see and feel the coombs cutting into the rim where the Masters lived. Tender pressure for their own coomb. A swirl showed where the sky lake filled the bowl. A touch at the centre where the edges of his palms met allowed him to feel the Isle with its Forbidden Garden within which lay the Pillar of Heaven and the Labyrinth.

Carnelian realized that his father's bright face had turned to him again. The storm eyes were deeper than the sky.

'Long have we lived here remote from the turning of events across the sea. But now they reach out to us and we can no longer remain untouched.' His father became granite. 'A time of peril comes for me

… and for you, my son. In the days to come we will have need of every resource.'

'What danger have our guests brought here?' 'Amongst many, themselves.' 'Lord Aurum?' 'He most of all.'

'Even though he is aligned to us by blood.'

'Blood trade insures neither amity nor alliance. My father gave my sister to be Aurum's second wife because he sought a son to replace the one who died in infancy. She has borne his House three daughters, a vast wealth should they live. But still, he has no son.'

'I did not know the children of the Chosen were so frail?'

'It is a curse of our race that so few come of age. Though the ichor of the Gods is watered down with mortal blood its fire cannot easily be contained by human veins.'

'I suppose it is that fire that kills their mothers too.'

'Your mother would have died a thousand times to give you life,' said Suth, misreading the look in his son's face.

Father and son examined each other's eyes. This was a subject they never spoke of.

Carnelian broke the silence first. 'And if Aurum were to die without a son?'

The second lineage of his House would inherit its ruling and House Aurum would be diminished among the Great.'

Then he should get himself another wife.' 'Do you forget that high blood-rank brides are the rarest commodity?'

'He has daughters that he can trade.' They are too young.' 'Iron then?'

His father's eyes pierced him. 'If he could have used such wealth, he would have.' 'And what of Imago Jaspar?'

'His House once ranked among the highest of the Great. More than two hundred years ago it sold the Emperor Nuhquanya a wife from whom today all those of the House of the Masks descend. Yet in the crisis over the succession of Qusata they lost their ruling lineage.'

'Slaughtered at his Apotheosis?'

His father nodded. 'Many Houses suffered.'

'So we are linked to House Imago's second lineage?'

'For more than a century it has been their first.'

'What is the nature of the linkage?'

'My grandmother was sister to his grandfather.'

'But our blood is purer than his?'

'Not so, in spite of your mother's blood having gifted you a blood-taint almost half of mine.'

Carnelian nodded. Irrespective of her august blood, he valued the father that he knew more than the mother he had never known.

'As you know, like all Chosen of blood-rank two, your taint has zeros in the first two positions. The largest fraction of your blood that is tainted is the eight-thousandth. In this third position you, Aurum and Jaspar have a one in contrast to my three. It is only in the fourth position, or the sixteen-thousandth fraction, that your blood differs from theirs. Whereas you have a nineteen in this position, Jaspar has a sixteen and Aurum has a fifteen.'

'So their blood is purer than mine.'

'Marginally, though neither of them can claim as you can to be the nephew of the God Emperor.'

Carnelian nodded at that familiar evocation of blood pride. 'And Lord Vennel?'

His father looked as if he had bitten into a lemon.

'He is of inferior blood. His father and his uncles, all of blood-rank one, conspired to buy for themselves a bride of blood-rank two. Their House had no blood to barter and little iron coinage and so her bride-price had to be paid with vulgar wealth.'

'Nevertheless, Vennel is of blood-rank two?'

Just, Suth's hand signed with a flick of contempt. 'He has the two zeros but a nineteen in the third. His blood is more than five times less pure than mine; ten times less pure than yours.'

'I like him as little as Aurum, but cousin Jaspar seems amiable enough.'

Suth clamped Carnelian's shoulders with his hands. 'If you think that, then he is to you a greater danger than the others. All who are Chosen are dangerous. In the Three Lands there are no beings so terrible as are we. Few of us know mercy, fewer still compassion. Inevitably, the greatest among us are the most rapacious. This is a necessity forced on some by the contest of the blood trade, on others by their nature. Constantly we hunt each other. Our appetite for power cannot be sated. We would eat the world though the gluttony destroy us.'

Suth stopped. He could see that he had frightened the boy already more than he had intended.

'Of course, you will think you know this,' he said more gently. 'After all, have we not spoken of it many times before? But accept it when I say that you cannot truly understand, for you have never walked in the crater of Osrakum. This is something that you feel with the fibres of your flesh or not at all. You have heard my words?'

Carnelian swallowed, nodded.

Then believe them.' His father's hands dropped away, his shoulders slumped.

Compassion made Carnelian bold. 'What burden are you carrying, Father?'

The greatest burden. Choice.'

The word was like a gate slamming shut.

They stood in silence. The green glass of the sea swelled up and from several points began to shatter white from side to side. Carnelian watched it, brooding over his father's words. Thoughts of the visitors worked their barbs into his mind. The salt wind blew hard upon his face but was not strong enough to lift his robe's brocades.

'Why have they come, my Lord?' he said at last.

'You will know that soon enough. Suffice to say that we will return with them to Osrakum.'

Images, hopes, dreams spated through Carnelian's mind. Osrakum, the heart and wonder of the Three Lands. More a yearning than a word. A bleak thought squeezed the vision still.

'Is their ship large enough to take us all?'

His father's eyes were fathomless.

As they looked out, both their faces turned to stone. The ominous movement of the sea seemed a mirror to their thoughts. Neither saw the storm brewing its violence along the southern margin of the sky.

A clanging on the doors called them back.

'Your mask,' his father said in a low voice and Carnelian remembered it and held it up before his face. His father's hand was a heavy comfort on his shoulder. The doors opened remotely and the beings came in, glimmering like dark water, their masks like flames.

Carnelian went with his father to greet them. With a clatter the day was choked out with shutters. They met the Masters by the fire in the crowding gloom.

'We trust you found sufficient comfort in your night's repose?' Suth said.

One of the apparitions lifted a hand like a jewelled dove. Sufficient, it signed.

Carnelian found the sign curious, made as it was by an unfamiliar hand. The Masters had discarded their travelling cloaks and were now clad in splendour. Their haughty faces of gold seemed a gilded part of the long marble swelling of their heads. Each was crowned with dull fire. Each wore many-layered robes, plumaged, crusted with gems and ivories.

'We shall needs be rid of uninvited eyes and ears.' It was Aurum's deep swelling voice.

Suth lifted his hand and at its command shadows flitted along the hem of the hall. The movement passed away. 'We are alone, my Lords.'

They unmasked. Carnelian felt something like surprise that the masks had managed to contain the radiance of their faces.

'Suth, your son is still here,' sang Vennel's liquid voice. Suth's response was cold. 'Is he not at least as entitled to be here as are you, my Lord?'

Vennel’s head inclined back and his eyes flashed. 'He is a child.'

Carnelian glared at Vennel's perfect face and was pleased to find his neck too long.

'In Osrakum, he would already have been given his blood-ring by the Wise,' Suth said.

Carnelian looked at the Masters' hands. Each was knuckled with rings like stars but on the least finger of each right hand there was a dull, narrow band. A ring of skymetal that grew bloody when not oiled. Iron, most precious of substances save only the ichor of the Gods Themselves. It fell from the sky in stones. A gift from the Twins to Their Chosen. The sign of Their covenant.

Jaspar smiled at Carnelian. 'Whether he wears a ring or not, I for one can see no reason to exclude him from our conclave.'

'Nor I,' said Aurum with over-bright eyes. Then let us begin,' said Suth.

Carnelian saw that five chairs had been set in a half-circle round the hearth. There was a hissing of silk as they each sat down. Their faces hung in the gloom like moons. They closed their eyes. Gems in their robes trapped fire-flicker. Carnelian looked down at his hands and wondered what was happening.

'Even now the Heart of the Commonwealth is failing,' Aurum rumbled, making Carnelian jump.

Understanding, Carnelian almost gasped. The God Emperor was dying. He watched his father's hand rise up to make the sign for grief. The other Masters followed him. Carnelian hesitated then copied them. He stared at his hand, making sure the sign was well made. He was relieved when the others' hands flattened to palms. Alone, his father kept his hand raised, but then he too let it go.