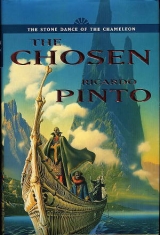

Текст книги "The Chosen"

Автор книги: Ricardo Pinto

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 21 (всего у книги 38 страниц)

AT HOME

A rose watched withering

Waits forgotten In this forbidden house

Youth's blush frowned grey

Perfume faded Left only her thorns

(from the poem 'Beyond the Siltter Door' by the Lady Akaya)

Although the pillar of heaven was already crowned with gold, the twilight was only thinning at its feet. Osrakum still slept. The narrow arc of the crater's faraway wall was still black. Only its glowing edge showed where the sun was beginning to set the sky alight. The lake was cataracted with mist. The Yden was grey. Carnelian inhaled sweet vaporous morning. He rubbed his cheek on the blanket. Its humming-bird feathers bristled and changed colour along the folds. He had climbed out onto the roof. His sleep had been troubled and that first gleam on the Pillar and the paling sky had drawn him with the hope of a new day.

The indigo above was growing blue. Carnelian looked south-west to where a mountainous buttress of the Sacred Wall hid the next coomb. He followed the wall's sweep round to the Valley of the Gate. There he watched turquoise begin to seep into the edge of the lake as if the colour were flooding out from the valley. The brightening crept across the lake to the Ydenrim and then up to reveal emeralds sparked with amber. Sunrise now lit the Pillar to its foot and speared its shadow back across the lake. Fire spread over the Labyrinth mound, caught on the flank of the Plain of Thrones. The sun's disc melting up from the Sacred Wall forced him to quit the roof for fear of it tainting his skin with its gold.

Carnelian grew solemn as he climbed back into the chamber. Today he would have to face his kin. The smell of sleep was coming off his body, but he did not feel like braving a shivering waterfall. Besides, the day's meetings were bound to require a formal cleansing and that required servants. He looked round for something to throw on. He wandered through several chambers but they were empty of everything but the echoes of his footfalls. Eventually he was forced to return to the small chamber in which he had slept in preference to the vast bedchamber Fey had given him. He removed the broken pieces of the jade spiral from inside his mask. When he lifted the hollow face he saw the letter that had been put under it. He stared at the perfectly folded, creamy rectangle. He picked it up and smelled its rich waft of attar of roses. Its wax seal bore the circular impression of a blood-ring. He broke it open. The parchment had only two panels. At first the glyphs looked strange. They were unlike the ones he or his father would make. He used the faces to gauge the differences in the style as his father had taught him. Soon the pictures were forming the sounds in his mind.

Sardian, you are returned. Your mother's eyes are impatient to behold you though they have so patiently waited out the years. Come, mount the steps. There is much that you must know.

He looked again at the ring of glyphs and numbers in the wax. It was as he had thought. There beside the Suth chameleon was the glyph 'Urquentha', his grandmother's name. He frowned. What had made her think that he was his father? He read it again then, folding it carefully, tucked it into the mask. He picked up the green robe. Its odour of lilies made him hurl it into a corner. Instead, he secured the feather blanket round his waist, picked up the mask and walked off to open the outer door.

A procession of pillars held back the shadow from an avenue that led off to a vague archway. He stopped to listen. Only birdsong embroidered the silence. He stepped into the hall, spreading his foot down over cool stone. He walked towards the grey courtyard.

When he reached its edge he looked across its fish-scale cobbles to the distant gates. The raised portico running round it was still in darkness. A flight of steps that led down to the cobbles was flanked by tripod urns of mossy bronze. He noticed a figure hunched on the end of one of the steps and padded towards it. When he was near he stretched out and touched it lightly on the shoulder.

The figure jumped to its feet and whisked round.

'Master…' it gulped. It was Fey, eyes wide, her hand pressed over her chest.

'Forgive me, I didn't mean to startle you,' said Carnelian.

Fey shook her head, panting, made uncomfortable by the apology and the glare of so much white skin. 'Master, I was waiting for you. I've taken the liberty of having some breakfast prepared.' She indicated a low table set between two columns, overlooking the courtyard. 'I've also sent for servants of all the different kinds so that the Master might choose a household for himself.'

'My own people will form my household.'

She darted a look of hope at him. 'Did you bring them all back with you, Master?'

Carnelian remembered his people blanketing the quay as he sailed away. The memory seemed from someone else's childhood. As he shook his head free of it, he noticed Fey looking at him anxiously. He smoothed his frown and even found a smile. 'We were forced to leave most of them behind. Ships will already have been sent to fetch them.'

'Ships…?' Fey stared off as if she could see their sails tiny in the distance.

Carnelian frowned. 'Are you telling me that you didn't know where we were?'

Fey pulled her eyes back into focus. There were rumours, Master.'

Carnelian pondered this.

Those you did bring with you, Master, will take more than thirty days to come through the quarantine. Until they come through…'

Carnelian thought of Tain, frightened and alone, arid of Keal and the others somewhere coming up the long, long road from the sea.

Fey gave an uncertain smile as she again indicated the breakfast table. 'I'm getting old and foolish, Master. I should've brought servants, garments…' She looked confused. 'I don't really know what I'm doing.' Her eyes dropped to her feet.

'Did you want to talk to me, Fey?' When the woman looked up at him he could see her need for news. He walked round her towards the table. 'It was thoughtful of you to arrange this. I'd very much like to break my fast while the air's still cool.'

He stood in front of the table. The dishes and bowls seemed to inlay the table like jewels. He thought of his people on the island, abandoned to famine. Fey moved a stool and he sank cross-legged onto it, putting his mask down carefully on the floor. Fey knelt beside him and began to serve the food. Carnelian put a hand on her arm to stop her. This is beneath you… aunt.'

She ducked her head to hide a blush. 'You're the son of… of the Ruling Lord,' she said through her hair. 'Nothing that I can do for you is beneath me.'

Then you'll eat with me.'

Fey looked up with her mouth hanging open.

There's no point in looking like that,' said Carnelian, trying to make her smile. 'It'll give me no pleasure to eat while you fuss around me. I'm not used to it.'

Fey looked at him as if she could not understand what he was saying.

'Sit there,' Carnelian said gently. 'I'd like your company.' He looked away when the woman awkwardly sat down, trying to save her more embarrassment. Carnelian picked up a box, opened it and offered it to her. Fey took one of the thin discs of bread as if she were being offered poison.

'Where will my father be now, Fey?'

'But, Master, you told me yourself that he was with the Wise.'

'Yes, but where would they have taken him?' To the Isle.'

The God Emperor… he's gone to see the God Emperor.'

Fey made the sign of the horns and ducked an obeisance. The Gods are in the Sky.' She gazed up between the columns.

Carnelian frowned, not sure what to make of the awe on her face. 'In the Sky?'

Fey came back to earth as she looked at him. The Master'll have climbed the Pillar… the Gods've gone up there to the Halls of Thunder, as your brethren, the other Masters of this House, have gone up to the Eyries.'

'You have my father's eyes,' said Carnelian.

Fey turned away as if trying to hide them from him. The better half of me is sister to the Master.'

'He told me to trust you.'. The words put tears in Fey's eyes. She dabbed at them. 'Please, Master, where's Brin?'

'Your sister had to be left behind.'

Fey's mouth twitched. 'Crail? He must be an old man by now?'

Carnelian looked down at his food, trying to find the words. He lifted his head. 'He's dead.'

Fey's face crumpled. She snatched a glimpse at his eyes. 'Grane?'

'We had to leave most of them…'

Carnelian could see by her face that she saw something of the conditions in which they had been left. She nodded slowly. 'Ebeny too?'

'She wouldn't come,' said Carnelian, biting his lip, hearing his voice betraying pain.

'Her boys, Master?'

'Keal's on the road, coming here. Tain's in the quarantine.' 'With others?'

Carnelian shook his head. Fey lifted a bowl of filigreed turquoise and offered Carnelian its peaches. Carnelian took a fruit, bit into it. He was vaguely aware of its sweetness.

'Our orchards are famous,' said Fey.

Carnelian looked at her and then the fruit. 'Yes… it is delicious.' He put it down. Fey lifted a ewer and poured water over his hands to clean them. Carnelian watched her put it down on its three legs. Each had a human form. Carnelian ran his finger over one of them.

'A Quyan piece, Master, and very rare,' said Fey.

'I promised my people that I'd make this place ready to welcome them,' said Carnelian. There won't be any problems, will there?'

She stretched a smile over her lips.

The other lineages resent my return?'

Fey looked at her hands.

'I see that they do.'

She looked up. Her face in anger was so like his father's that Carnelian started. 'It's not their place to resent you, Master. If you demand the Seal, they'll have to give it to you.'

She clapped her hand over her mouth. Carnelian could see her eyes expecting punishment. He gently peeled her hand off and squeezed it. 'You've not spoken out of turn.'

She frowned and regarded him as if he were a creature come alive out of a story.

'Please, tell me about the Seal,' he said.

Her eyebrows showed a flicker of surprise. 'Whoever holds it rules this coomb.'

'But my father…' Carnelian thought about it. 'It controls all our wealth?'

Fey gave a slow nod.

Carnelian suddenly understood something of the poverty of the Hold. 'But why did he leave it behind?' 'Without it here the coomb wouldn't work.'

'And you're trying to tell me that my father left all this power in the hands of the second lineage?'

Fey compressed her lips, shook her head erratically. 'Fey…?'

The Master left it with the Mistress.'

'You mean my grandmother?'

The Lady Urquentha,' said Fey, using the Quya.

Carnelian frowned. 'I have a letter from her.' He watched Fey go yellow as she dug her chin into her chest. 'What's the matter, Fey?'

Fey would not look up at him. She jerked back from the table, slapped her hands down on the floor and cracked her forehead down between them. Her abject prostration spiked Carnelian with anger.

'Get up, woman.'

Fey looked up with blood smearing above her eyes.

Carnelian winced. 'Look what you've done to yourself.' He reached up but she pulled away. He dug the letter out of his mask and held it up. This isn't for me, Fey, but for my father.'

The Mistress must've received garbled news, Master… the forbidden house… it's closed against the world… she's not allowed to see anyone…'

Carnelian examined her eyes as she rambled. 'Fey, what's the matter? Why are you so frightened?'

She hid her face again. He was trying to think what he could do when a deep clanging made them both look across the courtyard to its gate.

'By your leave, Master.'

He jerked a nod.

Fey rose and fled down the steps. Carnelian watched her recede. The sun was painting colour into the porticoes on his left. Friezes carved into the lintels animated their crowds of marble in the morning sun. A pyramid rose behind from which faces stared out. Beyond it was the striped green sky of the Sacred Wall.

Fey was labouring back towards him looking flushed and distressed. The Masters come.'

The second lineage? Down here?'

She gulped. 'Yes, Master.'

Carnelian's heart sank. 'Here?' He looked at the courtyard with its dead trees and then down at his body wrapped only in the blanket of feathers.

Fey shook her head. The Masters'll want to meet you on neutral territory… probably the Great Hall of Columns.'

Carnelian spread his arms and grinned. 'Shall I go dressed like this?'

She managed a smile. 'By the time we're finished, Master, you'll look like an angel.'

In a chrysalis chamber he stood naked while they painted him with camphor. Its evaporation was like drizzling quicksilver. Fey supervised the shaving of his head and then the polishing of unguents into his skin. In their shimmering perfume, Carnelian outshone the glowing circuit of the alabaster wall.

Inner robes swam through the air as lazily as jellyfish to engulf him. Layer after layer the robes grew heavier, the threads of their weaving more discernible, although the cloth was still so delicate that it would not hold folds but only, and temporarily, flakes of light.

'Do we really need more robes?' he said at last.

Fey looked horrified. The Master must put on an outer robe.' She clapped her hand to have them paraded. Each was carried by two servants like an elaborate piece of furniture. Some were panelled brilliantly with feathers. Others were sculpted into ridges of brocade up whose slopes climbed ladders of ivory and spinelled jewels. In honour of his father, he chose a sombre one of raven plumage flecked with bird-eye opals. His father's ring burned against his chest where he had hung it on a chain.

Fey had them bring Carnelian masks so fine that it seemed as if he held nothing but sunlight in his hands. He chose one whose face might have been stolen from a boy gazing out over a summer sea. Fey nodded her approval as they bound it on.

She surveyed her work proudly. 'All that is needed now is a crown.'

'A crown?' Carnelian's exasperation vibrated the gold skin of his new mask. 'I broil and the woman wants me to wear a crown.'

'You must wear a crown, Master, when you meet them.'

His head drooped. He had almost managed to forget the meeting with the Masters. He brooded as crowns were shown to him, many-tiered, like houses or ships, inlaid with precious leathers, haloed, startling with iridescing feather fans. He would have none of them. He overruled Fey and settled for a simple diadem of black jade. She herself climbed on a stool to put it on his head.

'Beware the father,' she whispered in Quya and then stepped down.

Carnelian thought to ask her what she meant but he saw the servants all around them. Thank you,' he rumbled and they all fell flat upon the floor.

Fey ordered a door to be opened in the alabaster wall. Beyond Carnelian could see only gloom. His skin felt as if it were being pricked with needles. He lurched into movement. The robes were heavier than armour. He had to breathe slow and hard to lift them with his chest. After a few steps he steeled himself but the tug of the cloaks never came. He turned his head as far as he could and glimpsed some of the children carrying his train. He looked back to the lamp-striped corridor and putting one foot before the other began to journey along it.

At first Carnelian thought they were a guard of diamond men, but as he drew closer he saw they were ice blocks. It seemed strange that such vestiges of winter should be found in this land where it was always summer. He passed through their cordon into cooler air, then through another of lamps and saw the two towers of sculptured silk awaiting him. Slabs of samite stiff with jewels joined by barrelling brocade. High in these structures, surrounded by coronas of quetzal plumes, was the gold of their disdainful faces.

As he stopped, he felt the mass of his robes settling round him. The green coronas inclined. He returned the bow. Sweat was soaking into his robes.

Facets flashed as one of the creatures began to move. A long white hand gleamed into being. Shall we be alone?

Carnelian lifted his arm against the weight of his sleeves and made a gesture of affirmation.

The other's fingers shaped a sign of dismissal. There was an impression of movement in the shadows. Carnelian felt something pull at his shoulders, looked round and saw the children arranging his train in folds over the floor.

'We have come to see if you are indeed who you claim to be, my Lord,' said one of the Masters. The voice was so deep it seemed to come rumbling down the avenues of columns.

'I am Suth Carnelian.'

'So you say,' said a different voice.

Carnelian was stung to anger but calmed himself. It was natural that they should seek proof. It occurred to him that he might show them his father's ring, but that was as lost beneath the layers of his robe as if it had been cast into the sea.

'My blood-ring,' he said.

He steepled his hands together and took it off. As he moved forward his cloak's drag made him feel as if he were yoked to a cart. If that inconvenience had been the Masters' intention in sending away the children, Carnelian was not going to allow them the satisfaction of acknowledging it. When he was close enough, he held out the ring. One of the Masters took it and held it up to the light. His gold face regarded it for a while, then gave it back. The Master reached down the slopes of his robe. His hands took hold of some brocade and pulled on it like handles. The robes billowed up like a wave. Behind this his jewelled torso began sinking. The silk subsided sighing as Carnelian realized the Master was kneeling.

'House Suth rejoices in your return, my Lord,' the deep voice said.

The other Master looked down at his companion, his hands fidgeting over his robe, but then he too knelt. When they removed their masks, their faces were snow reflecting a winter dawn. Carnelian unmasked as they were rising. Their beauty was much alike and bore no resemblance to his father's.

'I am Suth Spinel,' said the elder of the two in his deep voice. Carnelian recalled Fey's warning as Spinel's hand arced elegantly towards the other Master. This is my son, Opalid.'

Carnelian bowed.

'And what of the Ruling Lord, cousin?' asked Spinel. 'He has gone to the Halls of Thunder.' 'As He-who-goes-before?' said Opalid. Carnelian answered with his hand.

Opalid shook the green dazzle of his head. 'We never believed he would-'

His father slashed him silent with his hand. 'When is the Ruling Lord intending to return to the embrace of his family?'

'You are likely to know that better than I, my Lord.' 'Cousin, I become confused.' 'Surely you know why we have returned?' Spinel regarded him with cold eyes. To take back what is yours.'

Carnelian was surprised. That is far from being our prime concern. We have returned because of the election.'

'So, the Lord Aurum has yet again outmanoeuvred his enemies.' Spinel's tone was conversational but his eyes were sharp.

That remains to be seen,' said Carnelian, 'although my Lord might recall that my father has always been of independent mind.'

Opalid flickered a frown.

Spinel fixed Carnelian with his eyes. 'This delay in his return, though regrettable, does give us time to make all the required preparations.'

'You will quit those first lineage halls that you now occupy?'

Spinel's face became a cake of salt. 'Yes, my Lord, though you will appreciate this is something that cannot be effected in a moment.'

Carnelian nodded.

'In the meantime, perhaps, my Lord would condescend…'

Carnelian gave the Master an expectant look. '… to occupy the halls of the third lineage in the Eyries?'

'For the moment.'

'In less than a month we shall make the journey to the Halls of Thunder to vote in the election.'

'Am I to understand that my grandmother is up in the Eyries?'

Spinel gave him an enquiring look and a slow nod. 'I intend to meet her today.'

Spinel shaped a barrier gesture with his hands. The Lady is old now and frail and receives no visitors… the shock of this sudden appearance… not to mention-'

'My grandmother already knows that I am here.'

Spinel frowned. 'How could you know this, my Lord?'

'I have a letter from her.'

'A letter? I see.' Spinel put on a jovial smile. 'It seems then there is no problem whatsoever.'

Climbing into the palanquin, Carnelian felt like a jewelled doll being put into an oven. His train was fed in after him, the door slid closed and then he was hoisted into the air. The swell of the carrying poles damped away to stillness, then, with a sway, they were off. He breathed his hot, humid perfume slowly and tried to loosen some of his robes. He found a grille that he could open to let in some air. Walls and gilded pillars, glimpses of courts, manicured trees, all slid past in bewildering procession. He slumped back and fidgeted with his blood-ring, watching the play of light the grille freckled over the satin wall. He tried to ignore the heat, to think about his grandmother. His guts churned. What was he going to tell her about her son?

At some point the palanquin angled up and the pressure of its wall slid up to his back. He could hear a watery tumble and hiss. A mossy smell greened the air. He drowsed during the long climb up the Sacred Wall, as he was cooled and heated in alternating rhythms.

It was the palanquin settling to the ground that woke him. Carnelian sat up and put on his mask. He listened but could hear nothing. He slid back the door. Guardsmen knelt in a half-circle. They helped him climb out into their midst. When he straightened, he saw a columned hall running deep into the rock. Hugging the cliff, a wide stair with many landings wound down from where he stood, past galleries and colonnades, under balconies, round gargoyled buttresses. The whole cliff seemed to have been carved like a piece of wood. His eyes strayed to the stair's open side and he reeled. He gripped the balustrade that was all that lay between him and an infinite realm of air. The Skymere below might have been a sea seen from the clouds. The rim of the Yden traced its circle into vague distance, barely containing its emerald world that was all atremble with slivers of sun. In all that melting world the only solidity was the Pillar of Heaven. Carnelian leaned over the balustrade. The rock plunged down and further down until he saw the roofs and courts of the Lower Palace like a border of ivory plaques sewn into the Skymere's edge.

The air was cooler than it had been below. He drank it in so deeply that he felt his lungs were dragging him forward into flight. He turned his back on the sky and its beckoning fall and took some steps into the shelter of the columned hall. His train was lifted without need of his command. He reached out to touch one of the columns. His hand slid up and round the twist of its cabled stone, which was of a piece with the ceiling and floor.

As his eyes adjusted to the gloom he began to make out the guardsmen and the door that lay between them, which had moulded upon each of its leaves the womb glyph. He walked towards it and the guardsmen knelt. The door was of silver flecked with red and was stitched down the middle with several enormous locks. One guardsman rose and struck the door three times and then returned to his knees. Carnelian tried to lift them to their feet with a sign of command, but it only put more strain into their backs, and set their heads to ducking in apology, muttering, 'It's forbidden, Master, forbidden…'

Carnelian looked to the door. Its silver was a white garden, sinuous with flowers, pendulous with fruit, into whose riotous growth embedded rubies and amethysts drizzled their blood rain. He looked down the hall to where its last columns framed the glaring sky. He fiddled with his ring.

'How long will I have to wait?' he asked at last.

The guardsmen shrugged, hunching.

The door was struck from its other side and then Carnelian heard mechanisms operating. The guardsmen rose and a few of them lifted keys like fish bones and began to open the locks on this side. As the door began to open it breathed out an odour of mummified roses.

Carnelian walked through. More guardsmen awaited him but these seemed to have had their chameleons painted on their faces with blood. Though as tall as men, they had the shape of boys. It had never occurred to Carnelian that eunuchs might wear his cypher. The silver face of an ammonite came through them, and then another, both of whom were wearing purple. They bowed.

You were expected, one signed while the other lifted his hand shaping the sign, Close.

Carnelian felt the shudder in the air as the door shut behind him. On its other side, the guardsmen were resecuring the locks.

Seraph, all the standard procedures are to be observed.

Carnelian lifted his hands. I do not know the standard procedures.

The ammonites moved aside and indicated the wall behind them. In the stone, glyphs burning with jewel fire read:

The Wise certify this house appropriate to the sequestering of fertile women of the Chosen. To ensure blood line integrity, all creatures who are fully male are forbidden entry. Chosen males are permitted visits to the sequestered under the following, specific conditions:

First, before the visitor is admitted to this house, the sequestered shall be placed in a chamber of audience to which the visitor shall then be admitted accompanied by two ammonites;

Second, the visitor must submit throughout to supervision by the ammonites;

Third, the visitor must not touch the sequestered unless such touch is sanctioned by conjugal rite;

Fourth and concurrently, the visitor and the sequestered may make no exchange of any kind unless that exchange has been declared legal by the observing ammonites and recorded, said record to be submitted to the Wise;

Fifth, before the sequestered is removed from the chamber of audience, the visitor must have quit this house; all this by order of the Law-that-must-be-obeyed.

The words chilled Carnelian to the bone. One of the silver masks angled to one side. Shall we proceed, Seraph?

Carnelian broke his immobility with a nod. The slicking of bolts made him look to see them locking the door behind him.

'Seraph?' said one of the ammonites in a strange voice.

He turned to follow the creature's narrow back into the gloom. He could feel the other padding behind him carrying his train. He climbed a stair. On his right side, tunnelling slits were glazed at their further end with the brilliant colours of the crater. On his left, the stone was pierced to form screens behind which was a world of shadows.

They came to a door inlaid with red stone. The ammonite ahead of Carnelian scratched it. A woman's voice gave them leave to enter and the ammonite crept in.

The Lady Urquentha was the first Chosen woman Carnelian had ever seen. Her beauty lit the chamber like a lamp. A jewelled halo that framed her face took all its glimmer from her skin. The rest of the chamber was dark.

'You are not my son.' Urquentha's face thinned to fragile alabaster.

'Lady,' said Carnelian and made a clumsy bow. 'Did they not tell you?'

She gazed at him. 'Who would tell me? It has been my fate to know of the world only as much of it as I can see through windows. Rumours are the only communication to penetrate this house.'

'But your letter, my Lady, it came so swiftly.'

She frowned a little. That was delivered by my keeper ammonites. But how came it into your hand, my Lord?'

'I am the son of your son.'

Urquentha's face loosened but quickly tightened again.

Her hand began sending a series of quick signs to the ammonites which Carnelian could not read. He turned to see the creatures nodding, and when he looked back

Urquentha was gently beckoning him. He went as a moth to her flame. When he was in range, she asked permission with her eyes before reaching out to catch his chin. Her fingers were warm. He returned her gaze. Her eyes were peepholes on to a violet sea. She turned his face with her hand as if it were a vase she was checking for imperfections.

The hand released him and receded into a pearl-crusted sleeve. She looked sad. 'I can see nothing of my son in your face.'

Carnelian blushed.

She smiled. 'That at least is his. The rest is wholly your mother's. I should have recognized her beauty when you came through that door. Who else could you be but Azurea's son?' Her smile warmed him. 'Have you been made comfortable?'

'Yes, my Lady.'

'You may call me Grandmother, child.' Her eyes darkened to purple. 'You have spoken with the second lineage?'

'Lord Spinel came down to meet me, Grandmother.'

'Did he indeed,' she said, souring, showing the cracks in her marble face. She chuckled without humour. 'I would very much have liked to witness that fish floundering in the net he knotted for himself.'

A movement caught the corner of Carnelian's eye. He glanced round at the watching ammonites. With their numbers and fixed expression, their yellow faces could have been cast tallow.

'Where is my son?'

Leaning close to his grandmother, Carnelian whispered, 'Could we not be alone?'

'You wish to be free of my chaperons?' She turned a thin smile towards the little men.

Carnelian nodded.

She laughed like a girl. 'I more than you have wished to be free of those jaundiced faces, but it is forbidden by the purdah. But do not worry about them, Carnelian; they may have eyes but they have no ears.' She smiled at him. 'We were talking about your father.'

'My father, Lady… Grandmother…'

His grandmother used her hands to tease out his words as if they were a ribbon he had stuffed in his mouth.

'He has gone to the Halls of Thunder.'

Her lips narrowed as they pressed together. The jewelled structure around her head rustled and glimmered like a flight of beetles. She sighed. 'It seems it is always to be thus?' She looked through him as if her eyes were seeking the edge of the sky. 'Always it is the Masks that win the greater part of his affection.'

'He was hurt.'

Fear washed across her face.

'Wounded.' The word squeezed out of his mouth like a pebble.

'Will he die?' The words were flat and lifeless.

Carnelian could see the pain in her violet eyes. The Lord Aurum is confident the Wise will save him.'