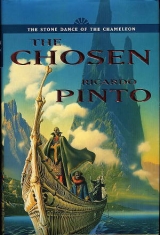

Текст книги "The Chosen"

Автор книги: Ricardo Pinto

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 27 (всего у книги 38 страниц)

They reached a door and passed into another chamber that was mosaiced with clouds of amethyst. His father stopped him there. He turned to him and stooped to hold Carnelian's face in his hands, then kissed him on the forehead. 'Did you think your father had forgotten your birthday?'

'I had forgotten it myself, Father,' Carnelian said in surprise. 'Is it already the thirty-third day of Jalod?' Suth nodded.

They had left the island in the last few days of the ninth month and here they were at the end of the eleventh. Perhaps seventy days in all. Those seventy days seemed a memory of years.

His father smiled at him. 'You are fifteen, a ripe old age.' He straightened up, looking away off into his memory, regaining for a moment something of his familiar beauty. 'I have never told you before that the day of your birth was also the day when the last God Emperor died. Birth during the broken mirror days of an imperial interregnum has momentous astrological implications. The first such day has particular significance. The Wise prophesied that fateful consequences accrued to your birth.' His eyes focused back on his son. 'At least your birthday has come before another such interregnum.' He frowned. 'What are those stains upon your supplication robe?'

Carnelian looked and saw the blood streaks. He looked up at his father and showed him the grazes on his palms. His father grimaced, glancing down his own gold brocades, and made a sign of apology.

There is no pain, Father.'

Suth jerked a nod. 'Come, let us hurry. I cannot afford to be long away from my responsibilities.' 'Where are we going?'

His father's sad face managed a smile. 'You shall see soon enough, my son.'

The echoing apartments grew colder and gloomier. Their wall mosaics became dark shifting nightmares. Everywhere there were doors and more doors, each guarded by its complement of syblings.

'Is it safe, my Lord, to wander thus unmasked?' Carnelian asked his father.

'Here there are no seeing eyes but ours,' Suth replied.

Carnelian longed to reach up and grasp his father's hand, but he was no longer a child.

At last they came to a door beside which a Sapient stood among a brood of homunculi. Their silver faces could have been snatched from sleeping children.

As Carnelian and his father came closer, one of the homunculi moved into the Sapient's cloven embrace.

'Who comes to the door of the Dreamchamber?' it said, eerily, a dead child speaking.

The Regent,' said Suth.

The Sapient reached out and tweaked the necks of the homunculi one by one. Carnelian recoiled as they crept forward feeling for his father with their hands. He watched them pull the crowns one by one from his head, then peel him free of his court robe. He stepped out of it, pale, narrow, like a worm cut from an apple. He climbed down from his ranga and was a man again. He turned and offered his hand. Carnelian could not read the strange, sad expression on his father's face but took it.

The Sapient turned and with his fist stroked the lintel of the door. It rang with a sound like a cymbal and after some moments began to open.

Myrrh misted the chamber. Ferns frothed up from the floor, curling, pushing up a giant sleeping. Sagging down towards them from the ceiling was a huge figure, like a man hanging face down in a hammock of spider's silk. Apple-green jade formed the circular floor that sloped up to the sleeping giant. Sapients squatted around the walls, their bleached skin tight as a drum's, their jet eyes staring, their lipless mouths valving open and closed. A dirge was oozing from them, a grating, grumbling chant that rose and fell as wordless as a wind. Somewhere a bell was being struck with a rhythm slower than Carnelian's breathing.

He followed his father towards the sleeping giant and saw that it was formed of the same jade as the floor. His father released Carnelian's hand. He felt the ceiling pressing down ominously and looked up at its black turmoil. It was like a man stuck to a ceiling with thick tar who gradually, under his weight, was dragging the whole sticky mass down.

Busy with this obsession, Carnelian did not at first register the feeling against his side. Then he gave in to its nagging, its brushing against his leg. He turned to see someone prostrate on the floor. For a moment he thought it one of the Wise who had slipped by him as quietly as a shadow, but when he looked anxiously for the comfort of his father Carnelian found it was him on the ground. Staring at him making the prostration, the hackles rose on Carnelian's neck. He looked up at the jade giant and felt a chill understanding seep into his head.

It was his father's grip on his coarse-weave robe that pulled him down to the floor and then a while later back onto his feet. Together they crept forward and began to climb the sloping jade. Carnelian's heart was louder than the chanting. As his eyes rose higher he saw that the jade giant was a kind of bed and that lying on it was a man, or something shaped like a man, a man whose face was mirror-black obsidian.

'Deus,' said his father, his head bowing. 'I have brought my son at Your bidding.'

Carnelian gaped at the Gods. Horror floated on the chanting of the Sapients. He saw one standing behind the giant's head that was a pillow for They. The Sapient leaned forward so that his fingers were touching the Gods' throat. He saw the thin yellow arm laid out along the giant's arm. Another Sapient, kneeling, had his cloven hands pressing on a vein running down the yellow arm. It looked as if he were preparing to play it like a flute. Yet another of the Wise, who held the wrist, was also striking the heart-stone bell. Carnelian's heart slavishly followed its peal.

'Even now, child, they use Us as an instrument to probe the sky for its Heart of Thunder.'

The voice rumbled from nowhere. Carnelian's eyes searched for its source.

'Later, when We shall dream, they assure Us that they will be able to chart its movement up from the sea.'

The non-singular pronouns registered. Carnelian stared at the Mask's obsidian lips and waited for it to speak again.

The other one, child, waits for a sign of Our dissolution. The moment of Our death will form a crucial part of their astrological calculations,' the Mask said. 'Release Us, Immortality.'

The Grand Sapient's noseless face frowned as he relinquished hold of the Gods' throat.

'Child, are you as mute as they?' the Gods said.

Carnelian swallowed several times, moistened his lips, breathed his voice to life. 'Perhaps… Deus… perhaps You will cheat them.'

The glassy face began a chuckle that came apart into coughing. 'We shall soon be occupying Our jade suit. A column in the Labyrinth gapes ready to receive Us into the second waking.' There was more laboured breathing. 'Sardian, the Mask impedes Our breathing.'

Carnelian watched his father's long fingers reach for the Gods' face.

Suth glanced first at Immortality and then at his son. Close your eyes, he signed.

Carnelian obeyed him, scrunching them closed, preparing himself for the blast of light as the Gods' face was revealed.

Carnelian heard the tempo of the bell increase a little. The tone of the Sapients' chanting changed as they reacted to it. He jumped when a hand touched his face.

'Kiss Their hand as a token of love. As much as They are Lords of Earth and Sky, They are your uncle,' rustled his father in Carnelian's ear.

Suth's hand guided his face. Smelling myrrh, Carnelian anticipated the scald of the Gods' skin. He cried out as something snagged and tore his lip; his eyes opened. He saw the narrow hand, the sharp ring, the blood pooling on the yellowed skin. His eyes snapped closed.

'Kiss,' whispered his father insistently.

Carnelian pushed his lips forward to kiss the slick of blood he had spilled on the Gods' palm. He drew back, licking the saltiness from his lips, muttering, 'Forgive, forgive…'

'It is only a little blood, child. What is a little blood between an uncle and his nephew,' said They.

The bell was ringing very fast in Carnelian's ears. 'Come, nephew, let Us kiss your hand. We will not meet again.'

Still tasting salt, Carnelian stretched out his hand, trembling for the touch of the Gods' radiant face. Cold fingers grasped his and drew his hand further. Carnelian flinched as the lips touched his hand. His thumb strayed onto other skin. Wetness. A thread of it under his thumb. Touching the tear track made him numb with terror. He withdrew his hand and stood back as his father and the Gods exchanged a muttering of words. He struggled to make sense of the sounds.

'… you must save my true son,' the Gods were saying.

Carnelian tasted his thumb. It seemed miraculous that Their tears should be as salty as mortal blood.

THE MOON-EYED DOOR

Without wings

He soared the sky

But when he fell

He fell like a star

(from the myth The Tale of the Three Gods')

His father had Carnelian move with his household deep into the Sunhold. From the nave of the Encampment of the Seraphim, they passed into a guardroom between bastions that lay to the right of the sun-eyed door. They traversed passages lined with loopholes and several double sets of portcullises before they reached his new chamber with its ambered walls.

It was there that he sat hunched, squinting at his thumb, hardly believing that it could be whole. He was outraged that its whiteness bore not the least stain to show where the divine tears had touched it. He remembered the gaunt yellow hands of the Gods: he had expected starlight diffusing through a membrane of adamantine. He remembered the weary voice from behind the Mask: he had expected it to shake the Dreamchamber as thunder shook the vaulting sky. The air had not thrilled with the ozone tang of lightning, but had been wreathed heavy with funereal myrrh. Inside the withered body, the divine blood had at best fluttered, a candle flame in a pavilion of stained parchment.

Was that a scratching at the door?

'Enter,' he said, then had to repeat the word more loudly.

The door trembled open to show a man holding a box. The familiarity of the chameleon on his face made Carnelian smile. The face froze, making its tattoo look like a gecko startled on a wall.

'Well, come in then,' said Carnelian. He had sent for one of his new household to clean him. It was a pretext. In truth, what he desired was to build a bridge over which he might cross to his new people. He needed friends.

The man was standing there as if the floor between them were strewn with blades.

'Come on, I don't bite. Are you intending to clean me from the other side of the room?' He intended this as a joke, but it only made the man more frightened. The wretch shuffled nearer, his shoulders curved, and, with maddening care, made sure to place the box soundlessly on a rug.

Carnelian stood up.

The man flinched.

Carnelian tried to smooth the frown from his face by smiling.

The man crouched and began to unpack the box onto the rug. Carnelian watched his short brown fingers with increasing irritation. He waited until the man had stood up with a pad, looking at Carnelian's skin as if it were some tower wall he had to whitewash.

'How're the lads?' Carnelian said.

The man stared at him.

Carnelian nodded, sculling his hand, trying to scoop some words out of the man's mouth.

'Master?' the man said, as yellow as a corpse.

The tyadra, the guardsmen, you know, the people outside with the weapons?'

They're… doing their job, Master.'

Carnelian was afraid that if he pushed for more the man might vomit. 'I see,' he said, and tried to stand perfectly still as the pad crossed the distance between them. It settled on his skin like a butterfly. Carnelian fought a grimace as the pad tickled lightly over his skin. Though he tried to suppress it, at last the laughter came like a gale.

The man stepped back gaping.

Carnelian struck himself repeatedly in the chest to quell the laughter. He pointed at the man. 'Gods' fiery blood, man, what… are

… you doing?' The man's knees struck the ground with a crack that made Carnelian wince, and then he hunched forward in a clumsy prostration. Carnelian stared, shaking his head. 'Get out. Come on, leave me. I'll clean myself.'

The man began to shuffle backwards.

'Stand up, and get out,' said Carnelian, not managing to keep the anger from his voice.

He watched the man leave, the door close, then sat heavily on the bed still staring at the door, shaking his head. He felt like crying or smashing furniture. They would all have to change. 'I couldn't bear it if they didn't,' he muttered. He imagined himself in Coomb Suth surrounded by fawning slaves. The chameleons on their faces seemed counterfeit. He nodded. His own people would bring change. He felt himself lighting up as he thought of them. Ebeny, Keal, Brin. 'Even Grane,' he sighed. At that moment he would have given anything for one of his scoldings. Tain.

Tain would soon be through the quarantine. The light dimmed. The first image of his brother that had come into his mind was of a vague face with blood running down it like lank hair.

'No,' he cried, stood up and walked about. There was no point in thinking about that yet. Time would come soon enough to count the cost. For now, he would allow himself to believe that his people would bring something of the warmth of the Hold back into his life.

The arrival of the Quenthas was announced to give him time to put his mask on. The syblings walked into the chamber and knelt. He strode over to them, pulled them up, easily managing to span both their shoulders. 'I cannot tell you how happy I am to see you.' He stood back to look at them. Left-Quentha had her head bowed but Right-Quentha was grinning at him all bright-eyed. He gave them both a bow. 'What brings my Ladies to this humble prison?'

Left-Quentha raised her stone eyes. 'Prison, Seraph?'

The Regent has sent us to amuse you,' her sister said.

'He did?' Carnelian frowned.

Right-Quentha shook her head. 'Oh, not like that, Seraph.' Then she smiled coyly. Though…?'

Her sister turned to her, frowning, then back to him. 'We have some skill with instruments, we sing and play a fair game of Three.'

Carnelian noticed the sword hilts appearing above their shoulders. He pointed at them. 'And can protect me?'

That also, Seraph,' they said together. 'I will allow you to stay on one condition.' Left-Quentha angled her head back, a little anxious.

'And what is that, Seraph?' That you call me Carnelian.'

For several days the sybling sisters strove to amuse him. They produced an instrument that had many strings, and frets and a gilded gourd at either end, and squatted with it on the floor. Their outer legs would have been called crossed if they had not been so far apart. Their middle leg folded under them. The instrument sat across their thighs. Two arms were under the neck, two over the strings. Their long fingers plucked and strummed all at once, coaxing cascades of sound, arpeggios, complex percussion. Sometimes they interwove their voices into the melodies, singing harmoniously, one voice sometimes chasing, sometimes shadowing the other. They could also play reed flutes made from hollowed saurian bones. As one blew a continuous drone, the other would waft over it rich, heart-rending melodies.

Carnelian became addicted to the strange game they called Three. It was played on a circular board with a black centre within two concentric bands of red and green. The three sets of pieces each took one of the colours. The sisters always chose the jade and the obsidian sets, smiling conspiratorially, saying the colours of the House of the Masks were naturally theirs. He acquiesced. After all, the red pieces were made of his name stone. He assumed they would ally against him, but instead he was ignored as they fought each other to destruction. He became tired of winning. Losing his temper, he insisted that they fight the game fairly and try to defeat him. They shrugged, grinned, and in the games that followed overwhelmed him. He rejected their offer that they should begin the game with fewer pieces. Slowly, he began to learn strategy from his defeats. The games became tortuous, subtle, merciless wars in which his red pieces began more and more to triumph.

Often, as they played, he would try to talk to the Quenthas about the election, the candidates, their factions. They met his questions with elegant deflections. They grew positively sullen if he ever strayed close to mentioning Ykoriana.

'No more music,' said Carnelian, adding quickly, 'though you play like the rain.'

Left-Quentha reached for the Three board.

'Not that either.' He stood up, stretched, groaned. 'My body aches from inactivity.' He frowned, locked his hands together and tried to tug them apart. 'I know,' he said brightly, looking at the syblings. Right-Quentha was wearing her green copper mask. At his insistence, she and Carnelian took turns at being masked. 'You girls can give me a tour of these Halls of Thunder.'

They both made evasive gestures with their hands. 'We would have to put you in your court robe, Carnelian,' said Left-Quentha. She glanced at it, an intruder gleaming in the comer.

'You might well come across other Seraphs,' said Right-Quentha.

'And then again, it might not be wise that we three should be seen together,' said her sister.

'It certainly would look strange,' said Right-Quentha.

'Strange,' echoed her sister.

Carnelian sank cross-legged to the floor. He propped his face up with his arm. 'You confirm what I have suspected. My father has sent you to keep me imprisoned here, in the Sunhold.'

The sybling sisters looked blindly at each other. There is nothing to stop us giving you a tour of the Sunhold.'

Carnelian brightened, leapt up, grabbed his mask. 'Come on then.'

They sallied out into the passage where they gathered up an escort of his tyadra. In the chamber set around with doors, the Quenthas pointed out the portcullises that they told him led off down long passageways to various gates giving into the Encampment. Between these were other doors which they said led into barracks. At his insistence they opened one and lighting a lantern they all went in.

'Soon this warren will be filled with a cohort of Red Ichorians,' said Left-Quentha and both sisters frowned.

'Apart from the side on which they are tattooed, how do they differ from the Sinistrals?' he asked them.

'In every way, Carnelian,' Right-Quentha replied indignantly. They belong to the Great and we to the House of the Masks. We live in different worlds.'

'Worlds…?'

Left-Quentha caught him in her stony gaze. 'We can no more be in the same world than my sister and I can be on the same side of the mirror as our reflection.'

Right-Quentha chuckled. 'Ours is a dark, looking-glass world.' She made them both dance a little.

The Halls of Thunder and the Labyrinth,' added her sister, forcing their three feet firmly to the floor.

Theirs is the world of the sun, across the Skymere.'

'And yet, on occasion, you permit them to come here into your world?' Carnelian said.

They both looked at him. 'It is a concession the House of the Masks makes to the Great,' Left-Quentha began.

'And only during such dark days as these,' her sister continued.

'And even then they have to lock themselves in here, within this fortress, from fear of us,' said the other, fiercely.

Carnelian smiled indulgently. They had taken on a poise that he could see was making an impression on the nervous faces of his guardsmen.

With a grin, Right-Quentha became a girl again. 'And would our dear like to see the chambers that will be his father's?'

Carnelian nodded and they led him back into the chamber of doors and across it to a golden mirror that showed the sybling sisters to themselves. This was a door that brought them into an atrium where the sisters said the tyadra of He-who-goes-before could defend their Lord. The guardsmen peered into the quarters leading off it that their fellows would occupy. Another gold mirror door was opened and Carnelian's eyes widened as he looked in. He followed the syblings into the chamber. The thick gold of the walls was moulded into wheels, rayed eyes and huge ruby-seeded pomegranates. The floor was fossilled stone-wood ribbed and lozenged with carnelian. Gorgeous apartments opened off on either side, every wall and door and ceiling a piece of jewellery.

When Carnelian had marvelled at everything, the Quenthas announced that it was time to see the Hall of the Sun in Splendour. They returned to the chamber of doors whose marbles seemed to Carnelian suddenly drab. A double portcullis was opened allowing them to walk down a tunnel into a vast columned hall. This too was panelled entirely with gold. Carnelian saw they had entered it through a side door. At the hall's far end, with their sun-eye, were the huge bolted doors that opened into the nave. Opposite them, behind a dais at the other end, the wall held a glowing mosaic of rosy gems that Right-Quentha called the Window of the Dawn.

'On that dais, your father will kneel to give audience to the Seraphim.'

Across from where they stood, down the long side of the hall, ran a series of tall and narrow amber windows. Carnelian walked towards one. He touched its mosaic of molten gold. The window formed the image of an angel like a man in flames; only the eyes of watery grey diamond suggested this might be a representation of a Master. Carnelian walked along the line of windows. In the terrible burning beauty of their faces, their eyes were such cruel winter.

Carnelian's foot stubbed against something on the floor. He turned to look down at it. 'A trapdoor?'

'It is nothing, Seraph,' said Left-Quentha.

‘Surely it must lead somewhere?'

'A fright of steps down to ancient halls.' Right-Quentha made a gesture to take in their surroundings. 'Precursors to these. Ruined now a thousand years.'

Carnelian imagined these ancient dusty wonders. 'Could we not go and see them?'

They are decayed, Seraph,' said Left-Quentha.

'Lightless,' her sister added.

'Filthy.'

Carnelian made a smiling sign with his hand. 'Just a peek?'

Right-Quentha could not help a smile.

'We must not,' her sister whispered to her.

'Just a peek,' said Right-Quentha. 'Where would the harm be in that?'

Left-Quentha turned away, blinking her stone eyes, pursing her tattooed lips. Her sister forced her to bend when she herself bent down to lift a handle in the trapdoor. Left-Quentha gave in. They crouched, took the handle with all four hands and pulled. The cover stone grated open, spilling light down the steps.

The Seraph should send his guardsmen ahead,' said Left-Quentha.

Carnelian turned to his men and saw with what terror they were peering down into the depths.

'What's the matter with you lot?' asked Carnelian in Vulgate.

They began to kneel. He focused on one and grabbed his shoulder to stop him. 'Well?'

'Master… it's said this whole mountain's hollow.' The man stared, slack-eyed.

'And so?'

The Gods and the Masters walk the higher levels but in the lower they keep… you keep…' The man's voice tailed off, then he whispered,'… monsters.'

Carnelian threw his head back and laughed. He turned to the syblings. 'It seems they are afraid.'

Left-Quentha regarded them imperiously with her stone eyes. 'Slaves are always afraid. Soon enough we will have them trotting down those steps.' The syblings rose, both stone eyes and living fixed menacingly on the guardsmen.

Carnelian lifted his hands. There is no point in forcing them. I do not want to be deafened by the chattering of their teeth. We will go alone.'

The syblings frowned. 'As the Seraph commands.' They walked round Carnelian, scattering his guardsmen. Each sister demanded a sword.

'I will go first,' said Carnelian.

'We will go first, Seraph,' they said together, showing the swords the guardsmen had given them.

Carnelian could see that they would brook no argument and stepped aside to let them lead the descent into the darkness.

Left-Quentha carried the lantern and Carnelian followed behind, peering between their shoulders at the steps revealed by its jiggling beam. Although the steps were smoothly cut, the walls were roughly hewn. The stair wound from side to side, and several times passed places where a porthole fed in a ray of daylight.

At last they reached the bottom and the Quenthas moved out into black echoing space. They lifted the lantern and spread its light across the floor to find the further wall.

'Behold the first Hall of the Sun in Splendour. No He-who-goes-before has stood here for a thousand years,' they whispered together.

Carnelian turned. The stair was a ragged rupture in the corner. 'Where is the gold?' he whispered.

It grew brighter as the Quenthas came up to him. Left-Quentha slid her hand over the wall and found something. Her sister caught Carnelian's hand and drew it to replace Left-Quentha's. He could feel a hole deep enough to stick his finger in.

The plates that were attached here were carried up there.' Left-Quentha pointed at the ceiling.

They wandered off across the chamber. The floor was mouldy with dust. The Quenthas showed him the dais and the blocked-up hole where the ancient jewelled Window of the Dawn had been. Carnelian walked down between the grim pillars to the door. Through its gaping maw was utter darkness. He called the syblings to his side. All three of them hung together in the door mouth casting the light out into a nave. Although this was on a smaller scale than the one above, it still ran off further than their light could reach.

Carnelian looked round him. 'Was this then the original sun-eyed door?'

In answer the Quenthas stood on tiptoe and reached up to touch half a hinge of twisted dull bronze.

'Please, let us go a little further,' Carnelian whispered.

The sisters turned to each other as if they were having a silent conference. Brandishing their swords, they took some steps into the nave. Carved columns ran off on either side. All together, they walked on, and however far they went their lantern found more columns.

At last their light showed a narrowing end to the nave, another doorway, its gates long ago torn from its jaws. Beyond more darkness spread without apparent limit. They crept into this.

'The ancient Chamber of the Three Lands,' whispered Left-Quentha.

'See,' her sister hissed as she tapped the floor with her foot.

Carnelian leant over but could see nothing but an age-pitted floor. He shook his head.

'Walk with us, Carnelian,' said Left-Quentha.

However lightly they put down their feet, their footsteps produced echoes. The syblings were feeling their way with the lantern beam as if it were a stick.

There,' muttered Right-Quentha and they rushed forward, keeping the beam anchored to a spot on the floor. They crouched and he joined them. He could see that the floor had two different zones divided by a black line. 'You see?' Right-Quentha tapped the nearest zone, 'Green,' and then the further zone, 'Red.'

Carnelian stood up, whistling his breath out. They cast the light round for him to see the curve. 'A wheelmap,' he hissed. They both nodded. They took him to the centre of the design where there was a third zone, a black disc like a hole into which was inscribed a turtle. They stood at the centre of the Commonwealth, in Osrakum. The syblings slipped the lantern shutter round to produce a narrower, brighter beam. They played it about to show him the faraway curve of the chamber's outer wall, and stopped at a gap. The House of the Masks' door.' Round to another. The Gods' door.' Round one more time. The beam sparked on an oblong of ice. Carnelian narrowed his eyes. Not ice, silver. As he made to walk towards it, they touched his arm.

He looked at their stiff spider-like silhouette. 'I only want to see it close up.' He could feel their anger but he went anyway and they followed, afraid to lose him in the darkness.

As he approached he saw it was a door of silver in the centre of which stared a huge crying eye. 'A moon-eyed door,' he muttered and remembered the other he had seen on the Approach.

'It is here as it has always been. The entrance to the labyrinthine chambers of the Wise,' the syblings whispered.

'Can we just take a look?'

They became like statues. 'It is forbidden, Seraph.'

He considered wheedling but decided he had pushed them far enough already. The other doorways?'

'Lead to the forbidden house.' They had gone cold on him.

'Shall we go back?' he said gently.

That would be advisable, Seraph.'

As they walked away, Carnelian snatched a regretful look back at the moon-eyed door, already a fading glimmer in the night.

When they returned to his chamber, they played a game of Three, but Carnelian's attention wandered. After two disastrous games, he told the syblings that he was tired and wished to retire early to bed.

He lay in the darkness, his mind's eye bewitched by a ghostly image of the moon-eyed door. It haunted his dreams so that when he awoke he was still tired. For breakfast, the Quenthas brought him peaches, fluffy hri bread and an aromatic paste made from honey and the tongues of hummingbirds. They played their flutes, they sang. He brooded.

It was afternoon when one of his tyadra came knocking at the door. The Quenthas answered it. There was muttering and then the syblings both turned to him and said, The Red Ichorians are come.'

They dressed him and together they went out to meet the new arrivals in the chamber of doors beyond the double portcullis that protected the access to his chambers.

A number of Ichorians were there waiting for him. As they removed their scarlet-feathered helmets and tucked them under their arms, Carnelian could see by the number of rank rings on their gold collars that they were all officers. One of them came forward, and as he knelt before Carnelian the others knelt behind him. The Ichorian touched the two zero rings and three bars on his collar.

'Master, I'm the commander of the third grand-cohort of the Pomegranates. I've come at the bidding of our father with a detachment of its third cohort to garrison this hold.'

Carnelian could see the fruit jewelled into his armour. 'I'm here by order of He-who-goes-before.'