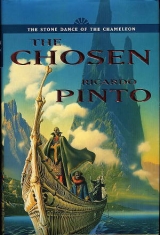

Текст книги "The Chosen"

Автор книги: Ricardo Pinto

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 4 (всего у книги 38 страниц)

THE BLOOD-RING

Apotheosis transubstantiates the blood of the elected candidate into ichor. The fractions of this holy blood that run in the veins of the Chosen derive ultimately from consanguinity with a God Emperor. Blood-rings are worn as symbol and proof of this relation. Each ring is inscribed with a blood-taint that can be found tabulated in the Books of Blood. Entries will be found arranged according to the Houses. The blood-taint of an offspring is derived by averaging the blood-taints of its procreators. (extract from a beadcord manual used in the training of the Wise)

Carnelian went to seek solitude among the summer pavilions. The courtyards he crossed were empty, unmarred, familiar. He entered one of the pavilions where a bloom of frost dulled the tiles. He wandered maskless, blowing his cloudy breath. He warmed a tile with a puff. Rubbed away the cold traceries to reveal the poppies beneath. He broke the pane of ice that filled the fountain bowl. He sat on a stone bench and recalled summers there but refused to indulge himself with tears.

At last he put on his mask and slipped back through the ruins, a shadow with a gleaming face. He passed scenes of torchlit industry that showed his world being destroyed. When he reached his room he closed the door and slumped back against it. The ache around his eyes had spread to make his face as stiff as the gold of his mask.

He waited, blinded by the flames. Tain came at last. They saw each other's pain. Before Tain had a chance to say anything, Carnelian sent him off to find Keal, and they came back together.

Carnelian looked at Keal. 'You look drained.'

Keal was sure Carnelian looked worse than he did, but he just nodded. 'I've been overseeing our work on the ship.' He hung his head. 'It's a nasty business.'

'Our stores?'

He looked up. That as well, but I was thinking of the ship. It's strange to wander in the warrens beneath her decks. You can feel the floor moving under your feet and hear her creaking all round you. It's brought back memories of coming here… when I was a child. And locked away in her sunless depths,' his frown creased the head of his chameleon tattoo, 'there are men, or something like men.' He shook his head, as if he were trying to dislodge the image in his mind. There was only enough light to make out the merest outlines, but they were there all right, you could smell them.'

'Sartlar,' said Carnelian.

Tain's eyes opened wide. They brought those monsters here?'

'Not monsters, Tain, half-men. Don't judge them too harshly. If it wasn't for them the Commonwealth'd starve. They work all her fields. Their labour is used everywhere by the Masters. They're not monsters but beasts of burden.'

'Monsters or not, I pity them there in that ship,' said Keal.

Carnelian looked at him. He imagined living out his life in the belly of the black ship, and he grimaced. ‘You've been to see the Master?'

Keal nodded. 'He and the visiting Master, the gigantic one, check on everything we do. Grane reports back to them about the work in the Hold and I tell them about the ship.'

'Work…?' snorted Tain.

They both looked round at him.

'When will she be ready, Keal?' said Carnelian.

Three days, maybe four.'

'Who's to go?'

Keal glanced at Tain. He began to list the names of guardsmen. Carnelian nodded at each name, considering the choices, asking questions. He stopped his brother when he began to list those not of the tyadra. 'You've not spoken your name, Keal.'

'I’m to go, and as commander. Grane's to remain here in the Master's place.'

'You don't seem overjoyed by your promotion.'

'I feel the honour, Carnie, really I do. It's just…'

'I know.'

'We're leaving them to die,' said Keal, close to tears. Tain's eyes were already wet. Carnelian would not allow himself to share their despair.

'Come, let's not give up yet. I've brought you here, Keal, to ask you if you'd do something for me.'

'Anything.'

'You've access to the Master.' Keal paled.

'Are the other Masters always with him?'

'Not all of them, just the terrible giant.'

'He frightens me as well, Keal, but if I'm to do anything I must speak with the Master. Will you ask him if he'll give me audience?'

'You ask when you could command.' There'll be no commanding between us.' 'Of course I'll do it, but don't count on it, Carnie. The Master's been stony since they came.'

While they waited, Carnelian had Tain clean off his body-paint. He was ready when Keal came back to say that the Master would see him. Keal had brought an escort with him.

As Carnelian walked through the Hold with Keal, he prepared in his mind what he would say. Along the length of the Long Court he looked straight ahead. He knew his father did not appreciate fevered argument. He must stay calm.

When they reached the sea-ivory door, Carnelian was relieved that only men of their tyadra stood outside. He squeezed Keal's arm. The doors opened before him and he went in.

'Perhaps you could help me choose which of these to take, Carnelian,' said Suth. He held up a folding-screen book whose binding was twisted with jewels. Many more books glimmered on the table beside him.

Reluctantly, Carnelian picked one up, smoother than skin, eyed with leather-lidded watery tourmalines. With care, he opened the first panel. Tracing his finger down the parchment, he unravelled the first two pictures into words.

'Books are doors,' his father muttered. 'And the glyphs are the keys that open them,' said Carnelian.

His father smiled at him. 'You remember that…?' His eyes fell again on the book he held, then looked up. 'Do you remember the lessons we had here?'

In this hall, his father had taught him the art of reading, and guided his hand as he scribbled his first thoughts on parchment with wavering lines.

'Thoughts are like butterflies,' he said.

Take care when capturing them lest you crush their wings,' his father responded. 'You know, it was necessity that drove me.' He shook his head. 'A Ruling Lord… teaching a child his glyphs…'

'And the crabbed, lifeless merchants' script…'

'… with which they trap wealth in their ledgers.' His father's lips always curled when he spoke of the merchants. Like all Masters he found commerce distasteful.

'But wealth is power…' said Carnelian.

'It is a fool who covets wealth, but he also is a fool who discards the way to power,' his father said. He saw Carnelian's expression. 'Have I said that many times?'

'I have it by heart. You showed me that my hands could' speak. The last word was a sign. Fingers are the lips and tongue of the silent speech. Their poetry of movement betrays the emotion behind the words. The words themselves are spoken without breath or sound by forming signs.

'You have a strong, clear hand.'

His father lifted up a book paler than his skin though not as radiant. 'As we have travelled together through these, so shall we travel through the greater world of which they are only impressions.'

'But what shall we be leaving behind, my Lord?' asked Carnelian.

'Famine,' his father replied. His lips compressed to a line.

'Is there no way, my Lord, we might ameliorate its harshness by reducing the amount that is taken by the baran?'

'Everything that can be done, my Lord, has been done.'

Suth watched his son's face harden with pain. 'You will have to face the situation as it is. The sharper blade leaves cleaner wounds.'

'Will the baran not accommodate more of our people? It is so large.'

His father shook his head. 'For all her bulk she really has very little space, Carnelian.' 'But the children, the elderly.'

The voyage would be as dangerous for them as staying here.'

'Father, are you not desolated by such loss?'

The marble of his father's skin was stained around the eyes. 'When we came here this place was a perfect mirror to my mood. That first winter was terrible. Many died. When they did not think I heard them, our people whispered that I had brought them across the black water to the Isle of the Dead. I think I almost shared their belief. As bleak and colourless as the Underworld is said to be, this island was worse. Perhaps if you had not been there swaddled in Ebeny's arms I might have let it remain always so. For your sake I let the household work upon the Hold. So far from Osrakum my hopes were ailing and wont to die. And yet in the years that have passed this desolation has become my home. It sits deep in my affection, perhaps more even than our palaces in Osrakum, of which all this' – he curved his arms out and round as if he were embracing the Hold – 'is not even a reflection in dull brass.' His father shook his head again. 'If my memory gives me true recollection.' He frowned and muttered, 'Sometimes that other life I had seems an impossible dream. Strange transformations have come upon me in this shrinking compass of my world. You know, my son, I have played roles that not even a Lord of the Lesser Chosen would stoop to. I have been brought closer to our barbarian children than I would have thought possible. So, in spite of all I am, all I know and all that I have been taught to feel, I must say, yes, I am desolated by this loss.'

They looked at each other, drawing a pale comfort from sharing their misery.

'Will Crail go with us?' asked Carnelian.

His father nodded.

Tain?'

Another nod.

'And Ebeny?'

'She has asked not to go and I will not command her.'

Carnelian considered this. She was more mother to him than nurse and, besides, his father's favoured concubine. He knew his father had feelings for her. 'I shall speak to her myself.'

'As you wish,' his father said and there was something like hope in his eyes. 'Now let us return to the problem of selecting which of these worlds we shall take as an accompaniment to our journey.'

Carnelian turned to the books. He looked sidelong at his father. The beautiful, tired face seemed intent upon the jewelled oblongs. A wave of dread washed its ice over Carnelian. His father was powerless. The Master, powerless. The Hold seemed suddenly precarious, as if a single wave might wash it into the sea.

That night, Carnelian slept hardly at all. Tain was having difficulty too. They played dice so as not to have to talk. They both played badly. Neither dared confess his dreams.

With first light Carnelian woke. He had left the shutters open just a chink and set a table against them to keep them from flying open. A thin light slipped into the room. Tain had turned away from it. In the corner, his blankets held him in their tight knot. Carnelian lay for a moment thinking. Noise carried up from the ship. Hammering. Voices. He rose and woke Tain to help him dress in his Master's robes.

From the alleyway, the Long Court looked like the carcass of one of the sea monsters that sometimes washed up in the bay that the gulls soon turned into a basket of bones. The remains of his home stood as stark against the colourless sky.

There was a sickening smell. Cauldrons had been set up from which palls of steam were spiralling into the air. Beyond, the cobbles were red with slaughter. Dread drew Carnelian to look closer. One cauldron was filled with bird-like heads and three-fingered hands jiggling in the boil. The long narrow saurian heads quivered white-eyed on pillows of pink-brown scum. He looked across to where they were skinning them, hacking the flesh free from the bones. Red hunks were being wrapped in leaves, and pushed into jars, and the spaces between were packed with icicles. Carnelian was horrified. He surveyed everything with pain-ringed eyes. All around him the mottled bodies lay, their gashed necks bleeding puddles over the stone, their arms and legs and tails curled stiff. This flock had been one of their chief treasures, the only source of eggs. He had loved to feed them from his hand. He recalled their bustle and their chatter.

He snatched at someone walking past. This was done for the meat?'

The man was all fear. He tried to fall to his knees but Carnelian held him up by one shoulder. 'And for glue, Master.' The man pointed crookedly at another of the cauldrons.

Carnelian let him go and went to look. Bones, and skin, the few feathers, all boiling up in a thick translucent broth. He recoiled from the stench. Through the steam he could see parchment laid out on the ground being glued up into sails.

He turned away, disgusted. Once more he plunged past the visitors' doors and onwards, but before he reached his father's steps he turned right. A small door gave onto a passage lit by a slit in the end wall. Once this had been his way to and from the Hold. It led to his old room overlooking the sea. Ebeny would be there. She had always been there.

He rapped on the door in the special way so that she would know it was him, then opened it gently. The room was large, frescoed with squid-headed ammonites and saurians with paddle limbs. The floor was scented grey-wood. This was his room. It would always be his room. Her room was off to the left. He took off his shoes to feel the whorls of the greywood with his toes. He unmasked and drank in the smell of the place. He walked across to the window. Through its panes of cuttlefish cartilage he could see the sea and the familiar curve of the bay. He frowned when he saw the ship there, sucking onto the quay like a slug.

She called out. He went through the doorway. 'Carnie, it is you.' Her brown, chameleoned face was filled by her bright smiling eyes. She stood up. She was less than half his height and had been beautiful. With a pang he remembered something his father had said about a barbarian's beauty being but a spring flower and quick to wither. He went forward and knelt before her.

'Come, come. You mustn't kneel to me, and certainly not in your Master's robes.'

He stiffened, stood up and moved to sit on a low stool beside her.

Ebeny looked at him, her eyes large and round. She reached out and touched the samite of his robe. 'You carry it well, Carnie.'

He blushed.

'You're upset.'

They have slaughtered the laying flock.'

Her lips pressed together, then she forced them into a smile. There's been much destroyed. But you can't make mosaic without breaking stone.'

'If it were only the stones of the Hold.'

She nodded. 'I know.'

'And yet you won't come with us?'

The Master told you?'

'Why won't you come?'

'Because, little one, I'm too old to travel on that sea.' She waved her tiny hand vaguely. It was the colour of sun-dried leaves and marked with the green of a child-gatherer's tattoos. Those tattoos had been among the first glyphs he had ever read. Eight Nuhuron. The God Emperor's name and the reign year when she had been compelled to come to Osrakum as part of that year's flesh tithe. He reached out, took it, covered the tattoos. Her hands were always warm.

'You are not so very old.'

She gave him a quizzical look. 'But I am so very afraid of the sea.'

He laughed, too loudly. 'You? When have you ever feared anything? You don't even fear the Master.'

'But still I'll not go. Your father came here before you and I gave him the same answer.'

He almost asked her what encouragements Suth had offered, what threats, but he did not. She had never broken his father's confidences.

'What's the real reason you won't come with us?'

She lifted up his chin and looked into his eyes. 'What I have become here, I cannot be in the Mountain. There, I will be nothing but a faded concubine to be thrown away like a worn shoe.' She made a throwing gesture. 'Would you hasten me to that?'

'My father'll protect you.'

'Even he must bow to the customs of your House. No. The journey'll be hard and your father's been long away. There might be problems and I don't want to be a burden to him.'

He drew her hand to his lips. 'But I might never see you again.'

'Fie,' she cried. 'It'll take a lot more than a little famine to rid you of me.'

He laughed though his eyes were filling with tears. He leant forward again. The coral pins of his robe rasped along the floor. He nestled his head into her lap. 'I can't leave you behind,' he mumbled into her thigh.

She ran her hands through his hair. 'Sush, sush, little one. You must do your duty to your father and your blood. You're a Master and can't allow yourself to get upset over an old barbarian woman.' She lifted his face up with both her hands. 4Do you remember when your father took you and Tain from me to live with the tyadra?'

He nodded his head in her hands.

Then you were leaving me to become a man. Now you'll leave me to go off and become a Master, one of the Skyborn. Would you waste your life out here so far from the centre of the world?'

He stood up. While she adjusted the stiff folds of his robe, he looked around her room, a room of treasures. He counted the plain waxed chests where she kept her robes and the ochre blankets that she made herself with their blue embroidery. He still slept with the blankets she had made for him though he had far finer. Even in the depths of winter something of the summer seemed to linger in their folds.

He turned round to look down at her. 'Will you give me one of your blankets to take with me?' 'You've several already.'

'But they've lost their smell of this room… of you.'

She smiled and kissed him and together they chose one. She pressed it into his hands. It was dull and crude against the beauty of his Master's robe. He pressed his nose into the blanket and breathed in. It gave him a chance to wipe away the tears. This'll do, old woman.' Once she would have boxed his ears. He realized now that even if she had wanted to she could not reach. He lifted her in his arms and kissed her neck. He left it wet with more tears. She was crying too. He put her down.

He made to leave but then her hand clasped his. 'Will you do something for me, Camie?'

'Anything.'

Take care of my Tain.'

Tain was her youngest child. Carnelian nodded. 'I swear on my blood, Ebeny, that I'll keep him by me and look out for him as best I can. Have you forgotten Keal?'

'He's a man now. He can take care of himself. One last thing.' She reached her hands behind her neck. They undid a thong and drew an amulet out from her robe.

'Your Little Mother?' Carnelian looked at her uncertainly.

She held it out for him. 'Wear her for me.' 'But she's all you've left of your mother.' 'As she gave her to me, now I give her to you.' 'Why do you not give her to Tain, Keal, one of your sons?'

Tish! You're as much my son as they are. Besides, if she protects you, you'll be able to take care of my boys. Take her. She has power over water.'

'My father will disapprove of her.'

'Well then, wear her where he won't see her.'

Ebeny kissed the Little Mother and put it in his hand. The carved stone was all belly and breasts with stump limbs and head. Carnelian closed his fingers over her.

The next day he went off into the pavilions but found no solace. He climbed up into the East Tower to survey the leaden sea. There, where he had first seen the ship, he spat curses into the wind that she had ever come. He longed for the old comforts, the old certainties. Yet, although he tried to deny it, Osrakum was drawing him with her siren call.

Masked, he returned to the pillage to see it all: the fallen halls, the gaping windows, the blood-rusted cobbles. He went out from the Holdgate and stood against the parapet. Handcarts creaked down to the ship, his people strained under barrels and boxes. He wanted to rail at them that they were collaborating with their own rape. The compulsion froze him to that spot for fear of what he might do. The ship became the entire focus of his vision. She wallowed down there, gorging herself on the general misery.

At some point he became aware of an ache in his knees. He looked down. Brackish water had soaked up from the hem of his samite robe. The silk was discoloured, spoilt. He remembered what Grane had said. His people had had shame enough. As he turned away the robe swung against his legs like an apron of lead.

He went back to his room. He lit neither fire nor lamp but chose to brood in the blackness, his robes and mask discarded, staring sightless, letting the misery torrent through him.

When Tain crept into the room, he raked the ashes but there was no glow left to find. He fumbled for a lantern that they kept in a corner. It fluttered into life. He jumped back startled. Carnelian was sitting cross-legged, black eyes narrowed against the glare.

‘I’ll not go,' Tain cried at his ghostly brother. ‘I’ll not leave my mother here, nor all the others. I'd rather die with them.'

Through the glare Carnelian could vaguely see that Tain's eyes were red and swollen. 'If I go, you'll go,' he said. He had neither love nor energy left to put any caring into his voice.

Tain stared at him blankly for a while and then ran away. Carnelian felt nothing. It was as if the winter had numbed him to the heart.

Later, a blindman brought him a casket of leather, ribbed and water-stained, which he put into Carnelian's hands. The Master bade me tell his son that he should attend him in his hall attired in the robe that has now been given to him.'

Carnelian asked him to leave one of his escort behind and then sent the man off to find Tain. When he looked round, the blindman had gone. Carnelian took the casket near the window to look at it. Outside, the twilight seemed to be sucking its darkening up from the sea.

When Tain arrived, Carnelian had already pulled the cloth out from the casket. It was the colour of spring leaves. It did not seem a robe at all, even though it had the hollow tubes for arms. The central band was plainly woven silk. The edges were brocaded in panels and fringed with eyes and hooks of copper. Carnelian ran his fingers over one of the panels. He peered close, feeling the beads. Rows of them. Jade, minutely carved.

Carnelian heard the door closing. He looked up and saw Tain's sullen face. His brother stared back at him. Neither spoke during the cleaning. At first they tried to put the robe on so that the panels were to the front. With much cursing they found that only when they put them to his back could Carnelian put his arms into the sleeves. Tain hooked the robe closed from top to bottom. It fitted well enough, though it was not sufficiently thick to keep out the cold. Carnelian did not allow his body to shiver. He took his mask from Tain's hands and put it on. 'I'll see you later.'

'As the Master commands,' Tain said, a cold fire in his eyes.

Carnelian had finally made up his mind. The destruction he saw everywhere strengthened his resolution. He reminded himself of the empty storerooms and the gluttony of the ship. He catalogued all the desperate looks he had seen on the faces of his people. But when he reached his father's door all he felt was the shivering cold.

Through the doors he saw a huge shape standing before the fire. It lifted up a hand in a sign of welcome. Carnelian crossed the floor to it. Its face was a shadow.

The Ruling Lord Aurum has brought you this,' said his father's voice.

The mass of his body swung round and Carnelian could see the hand held out in the firelight. He approached it. On the palm there was something like a hole. He reached out and took it. It was hard and warm. A ring of iron. A blood-ring that entitled him to cast votes in the elections of the Masters. He turned it in the firelight. Around the band's edge were the raised glyphs for his names and the spots and bars of numbers.

'He was given it by the Wise who had it set aside for you.' He gave his son a tender look that Carnelian did not see. The ring had him wholly in its spell. Its symbols were in mirrored form so that it could be used as a seal with both ink and wax. The eleven numbers confirmed the fractional tainting of his blood. He knew that it should be put on the smallest finger of the right hand. As the right hand signified the world of light so its smallest finger signified purity. It was too big.

There is no time for proper ritual. Even the preliminaries take many days. But there is much that is not essential. It is the Examination and the Rite of Blood that are the very nub and core of it.'

Carnelian looked up warmly at his father, then froze when he saw Aurum's face floating beyond his father's shoulder. Turning round he saw that Vennel was there too, his pupils the merest spots, and Jaspar with his idolic smile. Carnelian felt betrayed, as if his father had led him into an ambush.

Suth saw the change come across his son's face and said quickly, 'Witnesses are essential.'

The Masters circled Carnelian like sleek predators.

'Shall we begin?' said Aurum. His voice reverberated round the chamber. 'Lord Jaspar, it might please you to read the rings.'

Jaspar gave a little bow and accepted something from Aurum's hand.

The blood-rings of the Lord Suth and of his Lady wife, now long expired,' said Aurum. He turned to Vennel. 'Perhaps, my Lord, you would care to read the scars.'

'My hands do not have the seeing of the Wise.'

'Nevertheless, my Lord, we wish to be certain of impartiality, is that not so?'

'Oh, very well!'

Vennel began to move round behind Carnelian who, alarmed, turned to keep the Master in sight.

'Keep still, my son,' his father said.

Carnelian stopped turning and felt Vennel come up behind him.

The robe must be opened for your taint scars to be read as proof of your parentage.'

Carnelian fought a grimace as he felt the robe begin to slip off as Vennel undid the hooks down his back. He hunched his shoulders so that the robe would not fall to the ground.

'Exquisite,' he heard Jaspar say.

He closed his eyes. His perception was all in the skin of his back. He could not suppress a shudder when he felt Vennel's hands on him. Fingers sliding down the right of his spine, feeling the bumps and ridges that had been put there by the Wise at his birth, with a scarring comb.

'Zero, zero… three, aaah…' Vennel was reading out his father's blood-taint, 'fifteen, ahhm… nineteen, another fifteen.. . ten… two, no, three, now two, a final ten.'

'Is that what is inscribed on Lord Suth's ring?' asked Aurum.

'Exactly,' said Jaspar.

Carnelian felt the fingers lift away. He waited, grimacing. Vermel's hand was there again, to the left of his spine.

'Zero, zero, zero, two, one… three… nineteen, aaah… nine, six… teen, aaah… seventeen and a final… ten.'

The eleven fractions of his mother's taint. 'Confirmed,' said Jaspar. 'You can do the boy up, Vennel.' 'I certainly shall not. Am I now to become a body slave?'

'I will do it, my Lords,' said Suth.

Carnelian's shoulder was squeezed and the robe quickly hooked up. He turned and glared at the other Masters. Vennel was rubbing his hands as if he had touched something unclean. Jaspar was smiling. Aurum was as impassive as marble.

The Rite of Blood,' he said.

He came towards him until Carnelian was enveloped in his odour of lilies. He held out a vast leaf of a hand. An oval bowl lay along the palm, of jade so thin it might have been water.

This is the edge of the night,' intoned his father. Carnelian saw that his left hand held a razor of obsidian like a mussel shell. It sliced into the palm of his other hand. The cut beaded blood all along its length. The bowl in Aurum's hand was there to catch each drop.

Thou art my son, dewed from my flesh, Chosen. The ichor of the Two will burn thy veins; the same that once gushed from the Turtle's rending.' His father dipped his finger in the bowl. 'With this fire I anoint thee. In the names of He-whose-face-is-spiralling-jade.' He daubed a vertical stroke upon Carnelian's forehead. 'In the unspoken names of He-whose-face-is-the-mirror-in-the-night.' Dipping his finger once more, his father applied a second stroke beside the first.

Then Aurum's hand offered Carnelian the bowl. He stared at it, not knowing what it was he was supposed to do.

'Drink now thy father's blood that its fire might ignite thine to its own… fierce… burning,' said Aurum.

When Carnelian took the bowl he could not avoid touching the Master's stone skin. He looked up at his face. It seemed fashioned from dead bone with only two points of living light. Carnelian resisted its menace and drained the bowl with a single gulp, grimacing at the metal taste.

'On this day thou art come of age,' his father said.

Truly thou art chosen a Lord of the Hidden Land,' the others chanted, then they glimmered away like a tide on a moonless night leaving Carnelian angry, amazed, uneasy that he was now fully one of them.

'Soon the fire will begin its burning in your veins,' sang Vennel.

'Some days it will course like naphtha in a flame-pipe,' Aurum growled.

'It is one of the myriad burdens that we bear,' said Jaspar.

The price that must be paid for near divinity,' said Aurum. .'Nothing is without cost,' said Vennel.

Suth allowed his hand to brush Carnelian's. 'Yet, for many years, I have felt no burning.'

'How so?' said Vennel, his eyes frost.

Suth shrugged. 'Perhaps so far from its source its vigour fades.'

'Perhaps,' said Aurum. 'Perhaps.'

Tell me, my Lord Suth…' said Vennel.

Suth raised his eyebrows.

'Why did you have us perform this ritual here and now?'

'My son was past his time, and we had the ring here…'

'Aaah, the ring. My Lord Aurum was so thoughtful to remember to bring the ring. But still, are you sure that the Wise will consider it valid?'

The ritual had my Lords as witness,' said Suth.

'Are we qualified?'

'Our journey will be perilous. The awakening of his blood might afford my son some protection.'

Vermel nodded sagely. 'I see. And I suppose this coming of age could have nothing to do with the fact that the Lord Carnelian is now entitled to cast his twenty votes.'

'I do not entirely comprehend your meaning, my Lord.'

'My meaning, Great Lord, is that with your son and one other of us,' he glanced at Aurum, 'you can henceforth determine every decision that we make in formal conclave.'

That presupposes that my son will always choose to vote with me.'

'My Lord,' Carnelian said. His stomach knotted when his father turned towards him. 'My Lord, this conflict is unnecessary since I have decided that I shall stay with our household and follow after. It is for the best. I could be nothing but an encumbrance to you.'