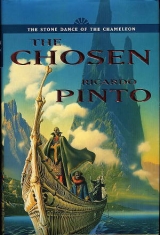

Текст книги "The Chosen"

Автор книги: Ricardo Pinto

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 28 (всего у книги 38 страниц)

'We've been instructed to protect you, Master.'

Carnelian watched the commander narrow his eyes at the Quenthas and said quickly, They too are here at his command.'

The commander and his officers were all shaking their heads in disagreement.

The Quenthas looked at Carnelian. 'Seraph, if they are here we cannot be.'

Carnelian could see it would be pointless arguing; the sisters had taken on their warrior stance. The Ichorians were squaring their shoulders in response.

'We shall leave now, Seraph,' the sisters said. They both smiled. 'We would not want to have to hurt them.'

'You must not forget your flutes,' he said.

Left-Quentha frowned a little but her sister allowed herself the slightest curving smile. Carnelian followed them back to his chamber and closed the door behind him, watching them pick up their instruments.

'I will see you again,' he stated.

They both looked up, expressionless. Right-Quentha shook her head. 'Perhaps, Carnelian,' her sister said.

Carnelian had a stone in his throat. 'I'm sick to my stomach of losing friends,' he said, in Vulgate. His words put sad expressions on the sisters' faces. 'Right-Quentha, please close your eyes. I am going to unmask.'

The sybling reached for the mask hanging around her waist.

'No, just close your eyes.'

They obeyed him. He went over to them, held the shoulders of each in turn and kissed her. They left him, Left-Quentha wearing a murderous frown that scattered the Suth guardsmen, her sister dabbing at her eyes.

For a while, Carnelian moped, missing the sisters. He went out to see the Ichorians, but the chamber of doors was empty. Only one pair of portcullises was lifted. He went to look through into the curving passage beyond. He remembered the guardhouse that was at its end, the same one he had passed through when he had come into the Sunhold. Its gates were near the sun-eyed door.

Remembering that golden door put him in mind of its silver sister in the shadow world somewhere beneath his feet.

What did he have to say to the Ichorians anyway? He returned to his chamber. He made patterns with the pieces of Three. He wrapped himself in blankets and went out onto the balcony. He watched indigo soak into the sky until the colour had grown so deep it was freckled with stars. His eyes became mirrors. The image of the moon-eyed door seemed to be hanging over the crater. He shivered. It was imbued with a longing that reminded him of the opium box.

He made his decision and came back into the warmth. He had his men bring him a sword, a lantern and a tinder-box. He made sure the lantern was well filled with oil and that its shutter opened and closed smoothly, and spent time honing the sword's bronze blade.

He rose with the moon, clothed himself, then left the chamber quietly. He silenced the question of the three guardsmen outside with an imperious hand and told them that they should not worry about him. If anyone came to see him, he commanded them to say that their Master was sleeping and refused to be disturbed. The eyes of one caught on the hilt of the sword. They could all see the lantern.

He left them to their conjectures and crept into the darkness of the chamber of doors. It was silent, with only a trickle of light and conversation coming from the Ichorians in their guardhouse. In front of the first portcullis that led to the Sun in Splendour, Carnelian carefully put down the sword and lantern. He slid the restraints from under the counterweights, braced himself against the bronze grille and, using the strength in his back and legs, lifted it a little. He pushed the sword and lantern under it and slipped through himself. He pushed the portcullis down and then opened and closed the second one in the same way.

The Sun in Splendour was pale with the moon that was a vague red eye in the Window of the Dawn. He stole across to the trapdoor. When he ground its cover back, he winced at the noise. He listened for Ichorians but they did not come. He crouched to light the lantern, shuttered it to produce a narrow beam, played this over the steps, then down he went.

The descent seemed to take much longer than before to reach the first chamber. He raked the blackness with the light. This is madness,' he hissed, frightening himself with his own echoes. For a moment he considered going back, then steeled himself and made for the gaping doorway.

The timbre of his steps changed as he moved into the vast sepulchral void of the ancient Encampment. He stopped several times along its nave, waited till the echoes fluttered away and listened.

At last he reached the chamber with its moon-eyed door. Only when he was halfway across it did he dare to lift the beam of light. The huge eye flared, irised with white fire. It was cut down the middle. For a silly moment, he thought that his light beam had sliced through it. He chided himself. The door was slightly ajar. He drew closer, close enough at last to touch its cold silver. He reached up to run his hand along the rim of the eye's lower lid to where it overbrimmed to spill tears the size of fists down the door.

He closed the lantern shutter a little more, took a deep breath and threaded its narrowed light into the gap between the leaves. The chamber beyond was filled with jewelled people and the ghosts of other lights. He snatched his head back, trying to still the betraying hammering of his heart. He waited for footfalls, a challenge. The only sounds were his heart, his breathing. He smothered the lantern in the lurid blood-red of his robe and dared to put his head through again. Perfect silent darkness. He uncovered the lantern to release its light. He let it impale one head. There was another beside it and another, as regular as sentinels. With a jerk, he realized a light was moving on the other side of the chamber. He lifted the lantern and it lifted too. 'Only reflection,' he breathed.

He squeezed through the door, trying to keep the light fixed on one of the heads, and reassured himself that its apparent movement came from his own wobbling. A bench, friezed with silver spirals, was the foundation for the glittering stumps he had thought were people. He stepped closer. Each stump was like three heads set one above the other. He reached out to touch the glittering surface. It was cold and knobbled like lizard's skin. He peered closer. Beads. Bead necklaces wound onto wooden reels. He reached up to touch the spindle that came up through their centres. Three reels impaled like pumpkins on a spear. He moved to the next three. Then there was an empty spindle followed by two more reel stacks. He walked round the bench and saw there was a second row of spindles behind the first. He stepped back and played light over the bench. On its side were four bronze loops from which hung short lengths of rope. He scooped one up, ran its beads through his hand.

He stood back, opened the lantern a little more, then held it up to look around the chamber. Twenty benches spaced out in a grid. The walls were the burnished heart-stone of the Pillar itself. He walked towards an archway. To one side hung a tapestry of glass, that he found was made of beaded ropes fixed to a row of loops set into the wall. He fingered one of the ropes, wondering what its function might be.

He shone light through the archway, then crept into the next chamber. This was very much like the first. It too had twenty benches with their spindles and reels, its near-mirror walls, its bead-rope tapestries. He wandered through another archway, another chamber, more arches, more chambers, each with its complement of benches. He wanted to find something that might make sense of it all.

He turned in the middle of a chamber. An archway opened in the centre of each wall. He could not remember which one he had come through. He closed his eyes, turning, trying to feel for the direction he had been facing. He opened his eyes and walked back to an archway. The next chamber looked much like all the others. So did the next, and the next. He grimaced. 'Fool, fool, fool.' He shook himself. Why had he not taken some precaution? He was utterly lost.

Thus began Carnelian's search for the moon-eyed door. Only the pulsing of the blood in his ears and his scuffling steps gave time shape. His path threaded the chambers as the cords did their beads. Neither made sense to him.

Huge whiteness reared up in front of him. His lantern clattered to the ground. He cried out and swatted at something with his sword.

'Gods' blood!' exploded a voice.

A blow made him drop the sword with a clatter. Falling to a crouch nursing his wrist, Carnelian stretched for the lantern that was angling its beam up to the ceiling. He felt the lantern being snatched away. Its beam fenced the air like a sword, then steadied to come down to run him through.

'Stay where you are,' the voice hissed.

Carnelian put an arm up as the light climbed to his face.

'What have we here?' said the voice as Carnelian tried to back away.

The lantern clunked down on a bench that opened to expose its burning heart. Carnelian blinked and saw the shape standing behind it. Long, pale Master feet stepped into sight. Carnelian looked up. The face reflecting the light made his eyes hurt. He narrowed them and saw a Chosen face, its beauty only marred by a birthmark on the forehead like the impression of a kiss. The eyes were diamond nails pinning the face to the darkness.

'Are you going to get up?' the face said, offering Carnelian a hand.

It was a boy not even his age. Carnelian slapped it away. 'I can stand without your help.'

The boy's eyes moved over him as if he were reading glyphs inscribed over Carnelian's body. It made him feel uneasy.

'You surprised me,' said the boy, now scanning Carnelian's face.

'You were the one lurking in the blackness like an owl. What by the burning blood were you doing?'

The boy's nostrils flared. 'Reading.'

Carnelian stared into his eyes, fascinated. There was something familiar about this boy. For some reason, Carnelian became embarrassed.

'In the dark?' he said, affecting a derisive snort.

'In the dark.'

Carnelian frowned, wondering if the boy was making fun of him. The boy's eyes moved elsewhere, allowing Carnelian's shoulders to lose some of their tension.

The boy stooped to pick up Carnelian's sword. He angled the blade, weighed it in his hand, looked up. 'Hardly a princely weapon, my Lord.'

Carnelian blushed.

'What did you intend to do with it?'

Carnelian felt silly. 'Protection.'

The boy raised his eyebrows. 'From?'

'How would I know?' Carnelian said loudly.

The boy turned the sword round and gave its hilt into Carnelian's hand. Carnelian laid it down on the edge of the bench. 'What were you reading?' he asked, to say something.

This.' The boy held up a necklace that sagged off into the gloom. He pulled, making more of it appear. He offered it to Carnelian who took it in both hands. The beads felt like teeth.

'Beaded rope?'

'Beadcord.'

Carnelian held it closer. Stone, and shell, and pink coral all carved into different shapes. The colours?'

The boy raised an eyebrow. 'In the dark?'

Carnelian grimaced. The shapes, then?'

The boy nodded. 'Run your fingers along it. No. Without looking at it.'

Carnelian closed his eyes and rolled a bead round in his fingers. 'A little ridge.'

'And the next one?'

Carnelian moved his fingers to the next one. 'Another ridge.'

'Feel again.'

Three ridges,' said Carnelian, feeling round the bead. The boy nodded approvingly. The first one is "earth", the second, "flower".' 'Jewel?' 'Exactly.'

Carnelian gaped at the beads. This is a story?' 'Rather a historical treatise.'

Then we are in a library of the blind,' said Carnelian, looking round him at the bobbins on their spindles.

'Of the Wise,' corrected the boy.

'Are they here?' Carnelian asked, suddenly alarmed, searching the darkness.

The boy's eyebrows lifted. 'Bound to be, somewhere.' He waved his hand. 'But there are many, many chambers and the Wise are preoccupied at present.'

'I shouldn't be here,' said Carnelian, lapsing into Vulgate.

'No,' the boy said in the same language, with the beginnings of a smile. 'And you?'

The boy looked amused. 'I'm as elusive as an owl.' 'I should leave.'

The boy shrugged, turned round and sat on something like a chair that was in a niche in the wall. He draped the beadcord over his knee and began counting its beads through his fingers.

'I think I'm lost,' said Carnelian.

'Yes, you would be,' the boy said without looking up.

Carnelian grew angry. 'If it would not incommode you very much, my Lord, I would appreciate it if you were to show me back to the moon-eyed door.'

The boy looked up and hooked Carnelian with his eyes. Carnelian withstood their brilliance with some difficulty. 'Give me your lantern,' the boy said.

Carnelian obeyed. He watched the boy walk off between the benches in a ball of light that was fringed with the glitter of beadcord. He followed him. They passed through seemingly endless numbers of chambers with the boy a black shape always in front of him haloed by the light. At last, they reached a door, its silver scarred with locks.

'Your moon-eyed door,' the boy said.

Thank you,' said Carnelian.

The boy gave a nod.

As he was turning away, Carnelian reached up and touched his shoulder. The boy looked at the hand as if it were the mouth of a snake. Carnelian withdrew it and found himself blushing.

'I was wondering…?'

The boy gazed at him.

'Would you consider teaching me to read the beads?'

The boy frowned. He stared down at his hands. They were long-fingered, clever hands. They looked so like marble that Carnelian was startled when a finger moved.

The boy was gazing at him. 'Be here at the rising of the sun and forget the sword.' He gave Carnelian the lantern, turned and disappeared into the darkness.

As Carnelian came back up into the Sun in Splendour, he felt as if he were returning from the Underworld. He looked back down the steps. The meeting with the boy seemed almost a dream. What had possessed him to arrange to go back and see him? As he made his way back to his chamber, Carnelian realized that he did not even know the boy's name.

BEADCORD

Fingers will read what eyes cannot see

With hands the deaf shall hear

Mutes shall speak with borrowed tongues

When the storm clouds draw near

(a Chosen riddle)

Before dawn, Carnelian lost hold of the edge of a dream and woke. He rose, cleansed himself, dressed, put on his mask and went out from his chamber. The watch guardsmen looked up at him with weary eyes. He stopped them kneeling with a gesture. They began to shuffle together an escort. He told them he had no need of them. When they sneaked glances at each other, he gave assurances that he would be safe.

He encountered no-one on his way to the trapdoor. He lit the steps with his lantern. Removing his mask to see more easily, he made his way down and then along the dark nave. All the way he kept telling himself that this was madness. The moon-eyed door was closed. He widened the lantern's beam and raked the shadows with it looking for the boy. No-one was there.

As he lowered the lantern its light washed around his feet. The door's huge eye stared tearfully over his head into the hall's black heart.

'Well, that's a relief,' he lied, as the disappointment washed over him.

The silver trembled as one of the leaves slid away, slicing the eye in two. Someone came out through the gap. It was the boy. His bright face made the door's silver look like lead. For a moment they gazed at each other. Then, saying nothing, the boy turned and disappeared. Unease blew out of the gap like a draught but still Carnelian followed him.

Through the mazing library Carnelian followed, watching the boy's white feet tread the edge of his lantern's light. They stopped between a wall and a beadcord bench where a niche cut back into the stone. Lifting his light, Carnelian saw one of the curious chairs on which the boy had sat the previous day.

The boy took the lantern from Carnelian and indicated that he should sit on the chair. Carnelian sat. He fingered the spike that rose from the end of the chair's left arm. The boy put the lantern down and turned to face one of the bench's spindles. He took hold of its topmost reel, lifted it free and then threaded it down onto the empty spindle next to it. He lifted the second reel from the original stack and turned with it in his hands. It could have been a human head wrapped in a jewelled cloth. Hoisting it, the boy impaled it on the chair arm's spike.

'What are you doing?' asked Carnelian.

The boy's hands were moving over the reel's beadcord. 'Hush!' He saw Carnelian's frown. 'In a web, a single vibration can bring the spider.'

'You mean the Wise?' whispered Carnelian.

'Do not look so fearful. I would know if one of them was near.'

'I am not fearful,' protested Carnelian, glancing over the boy's shoulder to scan for any movement in the chamber.

'Haaa,' the boy muttered with satisfaction as he found the beadcord's end. He pulled at it and the reel turned smoothly, glittering.

'First, we must teach you the basics. This is the most elementary beadcord I could find.' His fingers slid along from the end until they reached a faceted ring of bronze. This bead is where the reel's text begins.'

Carnelian peered at it.

'No, close your eyes. It is your fingers that must see.'

Carnelian held it then closed his eyes.

'What do you feel?' whispered the boy.

'It is angular, regular.'

'And?'

Carnelian shrugged.

'Is it not also cold? That shape with coldness will always tell you that you are at the beginning.

This here is the title of the reel.'

Carnelian opened his eyes to see the boy running his finger from the bronze bead along the twenty or so beads to the cord's end. The reel rattled as the boy yanked a long length of it, hand over hand. He coiled it up in his left, felt along it with his right.

'Here.' He offered Carnelian another bead to feel. This bead marks the beginning of a section and can be used to move accurately and rapidly backwards and forwards along the cord.' The boy pointed down to Carnelian's feet. 'You can respool the cord with that treadle.' Carnelian could see nothing, so he felt around with his toes until he found a plate. As he pushed, it gave way and the reel beside him turned a little, sighing some beads through the boy's hands.

'Here, take it.' The boy gave the loops of beadcord to Carnelian who pushed down with his heel then with his toe, and as he did so felt the cord spitting out of his grasp as it wound onto the reel.

'It is like a spinning wheel,' Carnelian whispered, smiling.

The boy nodded, all the time watching the reel. Reaching forward, he closed his hand over Carnelian's, lifting and dropping it in a smooth rhythm. 'Move it up and down so that it winds back evenly.' He examined the reel. 'If it is done untidily, a Sapient would know that someone unauthorized had been reading it.'

The soft warmth of the boy's hand contrasted with a hardness at its edge. As the boy took his hand away, Carnelian saw the blood-ring. He had thought him too young to have one.

The bones of the beadcord,' the boy whispered, once the cord was again taut and Carnelian had hold of nothing but its end, 'are the syllable beads.' He found some examples. Carnelian tried to memorize their shapes as the boy sounded them for him. 'Any text could be coded just with these, but perhaps to speed up reading – though I suspect more for secrecy – many words are represented by a single, special bead.'

'Like glyphs,' whispered Carnelian.

'Very much like glyphs. I have chosen this reel because it is composed mostly of syllabic beads. You must learn these before you progress on to the more esoteric ones.'

'Were you taught the beadcord by the Wise?'

The boy smiled enigmatically. 'You think that likely?'

Carnelian shrugged.

'Well, I taught myself.'

They allow this?'

The boy looked up at him with raptor eyes. They cannot forbid what they do not know. It is one of the arts the Wise keep jealously to themselves.' He rotated his hand to take in the surrounding gloom. 'I have counted more than six twenties of these chambers. Each has an average of twenty benches. Each bench can hold two dozen reels on its spindles. There is enough beadcord here to weave a garment that would clothe Osrakum's crater.'

Carnelian touched the reel. 'Each of these is a book?'

The boy wavered his hand. Three or four together can form a book. In contrast, a single reel can contain a dozen reports.'

Carnelian tried to imagine it all. 'A vast accumulation,' he sighed.

The exquisite distillation of millennia of dreaming and analysis.'

'And you can read all of it?'

The boy shook his head. 'If only I could. Much is hidden from me. This blind reading is a deep art. Some of the beadcord is as smooth as a snake.' He displayed his finger ends. These ten are like the eyes of fish in a muddy pool. The eight of the Wise see further than eagles. I have read a reel claiming that only the blind can see past the bright, false and shifting mirages of our mortal world into the immortal and immutable truth of the divine. It is said that the Wise do not only see what has been but what is yet to be. As in the glyph that represents them, they look over their left shoulder into prophecy.'

'Are they born blind?'

'No. At first they are like you and me, though of imperfect blood. They rise up from the flesh tithe that the Wise themselves impose upon the impure, marumaga children of the Great. After gelding, the candidates begin their studies in the Labyrinth. Those with winged minds soar up into the rarefied regions of the Wisdom. At every height there are those who can climb no further. Failing, they fall. They become the quaestors, the higher ammonites, the eunuchs of the forbidden house.'

'Blinding seems a poor reward for such a struggle. I had thought it punishment.'

'You are not completely wrong. The mutilations were imposed long ago when one of the Wise betrayed his trust. The imperial Commonwealth has her foundation in their silence.'

They are mute?'

They have only a single sense. Touch.'

'Surely they can taste and smell.'

The boy shrugged. 'It is rumoured that they retain a faint capacity to taste bitterness. That aside, they are in our world only by their skin. When they have achieved the highest wisdom that is allowed to those with eyes and ears, they are locked away. Each eye is sliced out like a stone from a peach. The red spirals of their hearing are cored from their heads and the fleshy shells shorn off. Caustic inhalations burn away their smelling and afterwards the useless meat of their nose is discarded. Their tongues are drawn out and harvested like the saffrons of a crocus. Once his mutilations are complete, a Sapient is left only feet and hands as the primary organs of his perception. Remote from seductive sensation, they can be entrusted with the deeper secrets. In the caverns of their cool uncluttered minds they are made capable of measuring the currents of our vast world minutely.'

They have their homunculi,' whispered Carnelian, seeking some salve for his pity, his revulsion.

The boy nodded. 'For each Sapient, his own, unique homunculus is a bridge into the outer world that if once removed leaves him as isolated as a rock in the midst of the sea.'

Carnelian looked off, understanding. 'No treasure chamber could be made more secure.'

The boy gazed at him, then snapped his eyes away to look at the beads. 'I thought you wanted to learn touch reading.'

Carnelian flinched at the harshness in the boy's voice. He took the beads and, slowly, they continued to work through the bead shapes. Concentrate as hard as he could, he still had to go back many times. His fingers became as raw as his mind, but the boy was relentless and Carnelian swallowed his complaints.

At last, the boy moved to the lantern and closed its shutter. For a while Carnelian could still see him standing there, but with each blink, his ghost image dimmed until Carnelian was in perfect darkness.

'Why…?' he whispered.

'Here in the library, darkness is the beginning of true seeing.'

Carnelian fumbled on through his lesson, coaxing words from the beads till he began to hear them speaking in his mind as if the beads were calling up through his hollow fingers.

The lesson is at an end,' said the darkness.

Carnelian was in a dream. As his fingers lost hold of the beads their voices went silent in his mind. 'But I have learnt so little,' he whispered.

'You can learn more, tomorrow. Wind the cord.'

When he pushed the treadle it gave an alarming rattle. Carnelian stopped.

'Why have you stopped?' whispered the dark.

The noise…'

'Our voices and not the treadle are alien here.'

Carnelian worked the treadle until he felt the end of the beadcord in his hand. Something brushed his finger and the cord was gone. He heard the reel being replaced on its spindle and then the other two being slipped down over it.

Carnelian felt another's skin link its warmth to his.

Take my hand’ whispered the boy.

Carnelian closed his fingers over the hand as carefully as if it were a throat. The lantern…?'

'I have it,' whispered the boy, firming the grip.

Carnelian was pulled off the chair. He became a ship being towed through a starless night. At first his steps were tentative, anticipating collision, but after a while they grew confident in the boy's impossible ability to see in blackness. Their footfalls dulled as they passed each archway and swelled again towards the centre of each new chamber.

The boy loosed his grip. Carnelian felt adrift, frightened. The lantern flared to life. He hid his eyes until he could bear it. With his free hand, the boy opened the silver door. Carnelian followed him out into the round hall. The boy held out the lantern and Carnelian took it.

The same time tomorrow?' Carnelian said quickly, as the boy turned away.

The boy looked back, nodded.

'I am Suth Carnelian,' Carnelian said before the boy could turn away again.

The boy gazed into the distance. Carnelian could see his reluctance to give up his name. 'I am of the House of the Masks,' the boy said at last.

They looked at each other, Carnelian willing him to say his birth name. The boy lowered his eyes. What shame was there in coming from the God Emperor's own House? Unless…? It came to Carnelian then. He realized whence the resemblance that had been nagging him came. He looked at the boy's face and imagined another identical beside it, sybling-joined. The likeness to the Lords Hanus was unmistakable.

'You have a twin?' Carnelian asked, letting the boy know that he knew what he was and did not mind.

The boy looked up. He raised an eyebrow. 'I do.'

Carnelian pushed warmth out into a smile. Although the boy was an unjoined sybling, his blood-ring proved that he was Chosen. His behaviour suggested that he was ashamed of his low blood-rank. In spite of being fathered by the Cods, his concubine mother must have badly tainted his blood.

'Can you not guess what my name is, then?' the boy said, both his eyebrows rising.

Carnelian shook his head, frowned. 'Should I?'

A slow smile spread over the boy's face. 'I am Osidian.'

'I am honoured to know you, Osidian.' Carnelian was glad that he was free of the blood pride that might have made him keep his distance from the boy.

Tomorrow, then,' Osidian said.

Tomorrow… Osidian.'

The boy went back through the door, and as he closed it behind him he healed the cut in the moon's eye.

The next morning, Osidian was waiting for Carnelian as he had promised. The boy said nothing as he led Carnelian into the Library of the Wise. The lantern light revealed the rich jewel seams of the beadcord as they moved through the chamber. At last they stopped at a beadcord chair. Again, Osidian urged him to sit down and going off came back with a reel that, in the dark, with his help, Carnelian began to read.

First they revised the syllabic beads but quickly moved on to more complex ones. Fluted spheres like coriander seeds. Glossy shapes like beetles. Beads with the texture of cold skin that Carnelian guessed were amber, others he knew were metal by the way they drew warmth from his fingers. Pumice, rough but floatingfy light. Wood, waxed and unwaxed. Each was a word, an idea. Fumbling them, Carnelian was reminded of learning his glyphs. Haltingly he whispered each bead's meaning. Whenever he stopped, Osidian's fingers would take the bead from him, and read it. Sometimes, Osidian would run his fingers back along the beadcord to find one they had read earlier and, squeezing it into Carnelian's fingers, would point out the similarities in shape or texture that reflected a similarity in their meanings. Thus, Carnelian discovered that each bead that represented a creature had a pimple head. That smooth curving often implied liquid; lightness, air; corners, something made by craft. The same shape with different temperatures often determined a spectrum of emotion.

Bead by bead, a story began to unspool in Carnelian's mind. Obsidian-faced, a God Emperor issued forth from Osrakum, riding in some fabled chariot of iron so huge it was honeycombed with chambers. With towered huimur They had gone southwards across the Guarded Land. Every being They saw They slew, being the incarnation of the Black One, the Plague Breathing, the Lord of Death.

'This is a story?' he whispered.

'History,' hissed Osidian. 'Read on.'

The annal continued. Somewhere along the southern edge of the Ringwall, the Gods descended with Their host. Down to a vast plain teeming with life. Carnelian could see herds shoaling like fish. Through this crowding flesh the Chosen host cut a swathe till the earth had been stained as red as the Guarded Land. Barbarian cities, rude, enclosed with wooden walls. The Gods' black tide lapped their ditches, igniting the palisades like the dawning sun. Carnelian bit his lip anxious for the next bead, impatient with himself when he could not find its meaning. As each squeezed like a pip through his fingers, he felt the earth shake, he was as blinded by the huimur flame-pipes as the barbarians. The beads let him look down from the vantage point of a huimur tower and watch the barbarians flee before their fire. Remembering the ants Aurum had torched on the road, Carnelian shuddered. Huts and children trampled by thunder. Their world turned to ash. The Gods swept, unsated, seeking new victims beyond the smoke-clogged horizon.