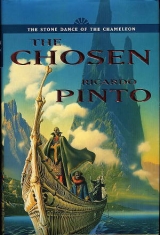

Текст книги "The Chosen"

Автор книги: Ricardo Pinto

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 10 (всего у книги 38 страниц)

They led him off to an arch and wrestled its door open. Some light spilled through, and something of the familiar smell of home. More of his people shuffled out to welcome him. Carnelian spotted Crail there among them, squinting, searching for something. When their eyes met, the old man's face scrunched up into a crooked frown. Carnelian dropped his mask into his hand and glared at him.

'You were told to stay hidden. Out of harm's way.'

The man scowled at him. Carnelian laughed. He took the old man's head between his hands and kissed it. There was a murmur of approval. The old man's smell was so familiar he wanted to hug him. Instead, he pushed him gently away.

He noticed Keal standing there behind the others, trying to hide uncertainty, and gave him a smile. 'Glad to see that you survived.'

Keal rewarded him with a grin. 'Many times I thought we'd sink.'

There were mutters of assent.

'In the future, let's try and avoid the sea,' Carnelian said.

Many of them beamed and nodded. Keal pushed his way through. The Master?' 'He'll be here soon and sent me ahead. Is everything ready?'

Keal grinned again, pointed at the arch's wards. These are proper Masters' rooms.' He reached out to caress his hand up the jamb, and Carnelian saw where the veined marble had been clumsily painted with the chameleon glyph. 'I did it myself.'

'Neatly done,' said Carnelian, wanting to be kind. He warmed when the other flushed.

Keal indicated the banners, somewhat crumpled from the journey, their poles locked into bronze rings near the door. He reached out tentatively, took Carnelian's arm and drew him through the arch.

The faces inside looked at Carnelian as if he were a fire in winter. Braziers had been lit. The balms the Master preferred were spiralling perfumed smoke up into the vault. Chameleoned blue canopies had been hung up to muffle the echoes. Mosaics had been polished. From somewhere they had managed to get bunches of irises and had sunk their purples and blues in vases of gold.

'It feels like home,' said Carnelian loudly, meaning it, enjoying their smiles. He turned to Keal. 'Where's Tain?'

'He's coming up with the rest of the baggage.' Carnelian nodded. 'Have I a room of my own?'

'Certainly you have, Carnie. I'll show you where it is.'

Keal left him. Malachite patterned the walls with the green of ferns in a dark wood. Smooth doors whispered open with a cinnamon waft. There were several chambers. One had a window paned with alabaster that softly lit a sleeping platform draped with feather blankets. In another, water ran waist high in a channel from which various sinks could be filled. In that chamber the floor was incised with runnels.

Back in the sleeping chamber, Carnelian discovered shutters and folded them back. Warm green-scented air seeped in. The purple vein-oranged sky made his eyes water. He fitted his face into his mask and stepped out onto the balcony. The balustrade was still warm but he dropped the mask when he found that the balcony was deep in shadow. It was an eyrie looking south. Half in shadow, the valley he had seen from the sea stepped its green terraces down from blue distance. Nearer, limes faded into dusty brown. Nearer still, a swathe of mudflats ran to a crisp edge of indigo sea. A causeway curving like the wingbone of a bird crossed the lagoon and wound the road it carried up into the terraces. Here it was already spring.

A sound from the chamber made him go back in. Tain stood by the door, panting, leaning back under the weight of a trunk his arms barely managed to embrace. Ointment boxes hung from cords around his neck. Clothes tubes were strapped to his back like quivers. He gave a thin smile, then looked alarmed, bent sharply over as a tube slipped from his shoulder. He managed to catch its strap in the hook of his elbow as Carnelian rushed forward.

'Let me take some of those. Couldn't you have asked for some help?'

'I didn't want any.'

Together they wrestled everything to the floor, then stood not looking at each other.

'Isn't this place enormous?' said Carnelian, trying to make conversation.

Too big,' his brother muttered.

Carnelian nodded. There'd be room enough in just these apartments for much of the household.'

That was a mistake. Thoughts of the Hold soaked them both with misery.

Carnelian punched his brother's arm. 'Come on, I want to wash.' Tain started rummaging amongst the stuff on the floor. 'What're you doing?'

'Finding the pads.'

There's no need for those,' said Carnelian and began throwing off his clothes. Tain came to help. 'I'll undress myself. The way you smell you'd better strip as well.'

Tain looked puzzled but did as he was told.

Carnelian's painted skin was mouldering like old whitewash. He pulled the Little Mother amulet over his head, coiled the strap and put her down carefully. He went off to the chamber he had seen earlier with its channel of water, Tain following with awkward steps.

With some experimenting and many accidents, Carnelian found out how to operate the various little bronze sluices. Soon he had created a number of crisscrossing waterfalls. Tain gaped. Carnelian crept behind him and shoved him in. Soon they were splashing round, screaming with the cold, letting the water spin rivulets through their hair. They gave themselves over to the delight. Both played with the sluices, pushing each other into any new deluge that erupted from above. They marvelled at the way the runnels in the floor kept the surface underfoot free from puddling. Tain rubbed the paint from Carnelian's skin. When they were both shivering clean, he ran out and found towels. While he waited, Carnelian turned all the water flow back into the channel running along the wall. Tain came up to dry him. Carnelian squeezed his hand when it came near and made Tain smile. It was good to see that.

Carnelian asked him to shave his head.

'Like the Master?'

'Like the Master.'

'But what if I cut you?'

'Well then, do it carefully.'

So Carnelian knelt at his feet while Tain first cut his hair almost to the roots with a knife and then scraped his scalp with a copper razor. Carnelian watched his brother working, his tongue held between his teeth. 'How are our people?'

Tain stopped, brushed a lock of black hair onto the floor, then gave him a sidelong glance. They're afraid.'

'Of what?'

'What's going to happen. And…'

Carnelian waited, looking down and playing with the hair that lay everywhere on the floor. He wanted to make it easy for Tain to say anything he wanted.

The killings… the killings on the boat. Everyone's rattled.'

'You as well?'

'What do you think?'

Carnelian relived the horror in his mind. The boy saw him pale and began nibbling the edge of his hand. 'It was my fault, Tain.'

'Maybe so. But there's other stuff. On the ship the lads heard things, sounds coming from the other cabins.'

'What sort of sounds?'

Tain's face creased up. 'Punishment sounds… other things… they're… we're afraid of the other Masters. And the Master, our Master, he's been behaving very strangely. The lads have even grown a little afraid of him.'

Carnelian felt a twinge of anger that they should dare judge his father. 'What can I do?'

'Keep an eye on them. You know they only live to serve you and the Master?'

The pleading in Tain's eyes melted Carnelian's anger. 'I know they do. Tell them that I'll do all I can.'

Tain beamed. ‘I told them you would, Carnie.' He made to kiss his hand, but Carnelian grabbed him instead and gave him a hug. They let go of each other.

'Now get on with my head.'

Together, they had stood on the balcony watching the sparks light up in the black valley all the way up the road. 'Like a river of stars,' said Tain in wonder. He turned to Carnelian who stood like an ivory carving beside him. 'Did you see the Master of this place, Carnie?' 'Yes.'

'Does he have a legion?' 'I'm not sure. Perhaps…'

Tain's eyes opened very wide. He reached out to touch Carnelian's arm. 'Do you think there're dragons here?'

Carnelian shrugged. T don't know.' It made him wonder himself.

Tain went inside and drew back the feathered blankets to sprinkle perfume on the linen sheets. Then he took a blanket and began to make himself a bed with it on the floor. Carnelian told him he could sleep with him in the bed. The floor's of stone. You'll have frozen to death by the morning and then what use will you be?'

In the darkness Carnelian nesded into his brother's warm back. He could feel the bumps down his spine. They had not slept in the same bed since they were infants.

'Do you think we'll see dragons?' whispered Tain. 'I'm sure we will,' Carnelian replied. 'Now go to sleep.'

RANGA SHOES

The Chosen shall not set foot on earth, nor stone, nor any other ground outside Osrakum that has not first been purified in the manner prescribed.

(extract from the Law-that-must-be-obeyed)

'Carnie. Carnie.'

Carnelian woke and had no idea where he was. The Master has sent for you.'

It was Tain with an intense dark gaze. Carnelian sat up and swung his feet onto the floor. He rubbed his face, knuckled his gummy eyes, then stood up shakily. He lifted his arms out to the sides and screwed up his face in anticipation of the cold touch of the pad.

Tain pushed Carnelian's arms down gently. 'I was told not to clean you.'

'Sorry?'

'You are to go as you are.'

Carnelian stared at his brother, confused.

Tain chuckled. 'Well, not exactly as you are. You're to wear this.' His chin nudged a black garment draped between his outstretched arms.

Carnelian bent forward to allow Tain to feed it over his arms and head. Tain stroked it smooth then did up its spine of hooks. Carnelian yawned. He ran his palms down over the crusty brocades. 'What sort of robe is this?'

Tain shrugged. Annoyance pushed its way through Carnelian's sleepiness. He lifted up some of the black cloth, peered at it, traced its patterns of glassy beads with a finger. He felt he should be able to read them. He could not. He shook his head and let the cloth drop.

Tain led him out from his chambers. Carnelian felt unwashed, naked without his paint as he walked out into the great hall where the blue canopies were billowing. Doors were open, leading off in a long succession to the predawn sky. His people were face down on the mosaic. Tain joined them there. A door hissed open with an exhalation of lily. His father appeared, narrow, tall, his face fearfully white, clad in an identical black robe. Someone with eyes averted handed his father his mask and he hid his face like the moon behind a golden cloud.

'See,' his father commanded.

Their people looked up and then rose to their knees. Keal and the other guardsmen began rising to their feet.

We go alone, his father signed, using the Lordly 'we'. He paced towards the outer door. Carnelian fell in behind him, scratching an itch on his head, startled when he touched stubbled scalp. He had forgotten the shaving. The hard edge of his mask pushed into his hand. He smiled his gratitude at Tain, put it on, then followed his father's back, watching the black samite bunch and loosen with each pace. The doors rumbled open and they passed into the gloomy hall beyond.

They walked down the centre of the hall. At the end was a tall door before which flames leaping in braziers were the only guards. Silver ammonites embossed the door like startled eyes.

'My Lord, why would the Legates use their legions against Osrakum?' asked Carnelian, feeling the need to almost whisper.

His father did not turn his head but kept his eyes fixed upon the door. The Legates and the commanders under them are all, naturally, of the Lesser Chosen. The God Emperor appoints them all. They serve the House of the Masks. It is their only source of wealth.'

'Because they are excluded from the division of the flesh tithe as well as the taxes from the cities?' said Carnelian.

His father nodded. 'Although they form no part of the Balance of the Powers, they hold in their hands almost all the military might of the Commonwealth.'

'And it is feared that they will take with force what the Three Powers would keep wholly for themselves?'

They had reached the door. Flames flapped like hands in spasm. Carnelian glanced up. Flickers of their light were trapped in each tarnished spiral.

'Quite so. We have taken many precautions against them, chief of these being that we hold all they possess and care for within the Sacred Wall of Osrakum.'

'But if they have the legions…?'

The Great have the double-strength legion, the Ichorian, and with this we hold the Three Gates into Osrakum.'

'Would it not be safer to include the Lesser Chosen within the franchise of the Great?'

His father looked down at him. Then the legions would be ours and the Balance would be broken.'

'Could Legates not be appointed from the House of the Masks itself?'

'No-one of the Imperial Power can ever be permitted even to cross the Skymere to its outer shore. If ever that happened, and they managed to escape Osrakum, they could use the legions to overthrow us and again the Balance would be broken.'

Carnelian gaped. 'What you are saying, Father, is that those of the House of the Masks are prisoners of the Great.'

His father was eyeing the gloomy length of the hall. 'Say, rather, hostages.'

The Great hold the God Emperor Themselves hostage?'

'As They in turn use their legions to hold us hostage in Osrakum. That is the Balance.'

'And how do the Wise form part of this Balance?'

They are the Law made flesh. Inside Osrakum they constrain the freedoms of all the Chosen. Outside, they maintain the roads with their watch-towers and the left-ways with their couriers. Though blind, there is nothing in the Three Lands they do not see. Additionally, it is their ammonites that form a seal across the Three Gates. They keep the inner and the outer worlds apart and form the only bridge across the divide. It is only at their sufferance that we ourselves are permitted to be here, outside Osrakum.'

The Balance must restrict their power?'

'In terrible ways, but essentially the God Emperor's guardsmen, the Sinistral Ichorians, hold them hostage.'

'And we, in turn, hold them all hostage.'

'Rings, within rings, like the ripples on a pond.'

'Moving outwards from the God Emperor, a leaf dropped from the sky.'

'Just so.'

'Father, are these quaestors then the Wise?'

His father's hand flicked a dismissive gesture. 'Of the Wise, Carnelian, but not the Wise themselves. Surely, if you noticed nothing else, you could see the quaestor still had eyes?'

'Of course… I was careless. What manner of…?'

'A failed candidate for the Wise, though he came so close that I marvel that he kept his eyes. I was not able to examine his face fully but it seemed to me that he had passed many of the higher examinations.'

The numbers?'

Their positions relate to the different lores, levels, domains.'

'And what is the Privilege of the Three Powers?'

'It is a law that allows each power the right to exclude either or both of the other two from any matter that it considers internal to its affairs, unless this exclusion should be precluded by another law of higher rank.'

'And so you included the Legate as the representative of the God Emperor while excluding the quaestor who is a representative of the Wise because you intended to overrule a law?'

Suth made a gesture of impatience. 'You ask too many questions, my Lord.'

'Knowledge is the best armour,' said Carnelian with a flush of anger.

Suth looked down at his son, recognizing his own words. There is something I must tell you.'

The tone of his father's voice made Carnelian's stomach clench. At that moment there was an echoing sound of doors closing. Father and son turned to look down the hall. The other Masters were walking towards them, hands and feet pale as the dead's. Three of them, shrouded in the same black robes, coming as for an entombing.

'What did you want to tell me, Father?' whispered Carnelian anxiously.

Not now, his father signed.

Carnelian was forced to stand silent at his father's side as they watched the Masters approach. Aurum moved out in front of the others. Carnelian and his father made way for him. The old Master moved between them to strike the door. Each blow was answered by a deep vibration. 'We are come because the Law must be obeyed,' Aurum boomed.

Exhaling camphor, the door sighed open just a body's width. One by one they rustled through. A vapouring milky pool lay on the other side. Carnelian watched his father wade through, the hem of his black robe floating round him like a slick of oil. Already past the pool's white lip, Aurum was moving off leaving a glistening track.

Vapours spread chill up into Carnelian's nose. He lowered his right foot into the liquid. Biting cold washed over it. He put in the left foot, then he dragged his train across. As he splashed out the other side, he saw that his father was ahead of him, talking with his hands to Jaspar. Carnelian turned to see Vennel walk across, his narrow hands hitching up the skirt of his robe, revealing long marble legs, so white they made the pool look yellow.

Tall bronze lamps lit benches of stone, upon one of which Aurum had sat down. Sallow creatures appeared and fussed round him. Carnelian found a place beside his father. As he pulled up his soak-heavy robe it gave off a reek of camphor. Jaspar and Vennel were setding on other benches.

'You who are Chosen shall now make ready to leave this place.' The words were spoken in Quya but did not have the rich timbre of a Master's voice. Carnelian located their source to be the quaestor in his purple samite. His face of polished silver had a mouth but only solid spirals for eyes. In his hands he held a cord like a necklace of beads.

'You who are Chosen must take all precaution before crossing the Naralan and the Guarded Land,' said the quaestor, counting the beads through his fingers as if he were using them for prayer.

Carnelian heard the other Masters answer him, 'As it has been done, so shall it be done, for ever, because it is commanded to be done by the Law-that-must-be-obeyed.'

The covenant you made with Him, the Dark One honours. In the hidden land of Osrakum He will not incarnate though His anima share the inhabiting of the God Emperor with His brother. Beyond the Sacred Wall, all other earth unto the sea He has soaked with pestilence and plague. In these His domains you shall walk under the restriction of His Law as your fathers have done before you. This is His Law as it has been written in the Plain of Thrones.'

Carnelian felt his father's warm hand stray over his own.

The Chosen shall not stand within two fingers' breadth of unhallowed ground,' chanted the quaestor.

All the Masters made the same response as before and Carnelian mumbled along with them. He turned his hand palm up to grasp his father's as one of the slaves knelt before him holding a casket. Bones pushed through tallow skin like blades. Another slave leant over to open the casket. Her torso was a basket of ribs. In place of an ear a hook-rimmed mechanism of brass snagged into her face. She drew out the ranga shoes and placed them in Carnelian's lap with more care than if they had been painted with poison. Each was of wood lacquered black: a long and narrow platform for the foot, securing straps and, set transversally on its underside, three supports a few fingers' width deep: one painted black, one red, one green, presumably in token of the Three Lands.

'My shoes have been tampered with,' said Vennel sharply.

Carnelian looked up. His father and the other Masters had also been given shoes. All were turned towards Vennel.

The Master held up a shoe. The supports have been trimmed.' He displayed it for all to see.

The modification was carried out at my command,' said Aurum.

'One cannot-'

The full height would encumber us on our journey, my Lord. Quaestor, do they still meet the requirement of the Law?'

They do, Seraph,' said the silver mask. Aurum turned back to Vennel. 'Might we be allowed to proceed?'

Vennel made an affirmative gesture shaded with anger.

Carnelian felt his father's hand moving in his own. It escaped to sign, Copy me.

Carnelian watched his father search the hem of his robe. When he found a single embroidered glyph like a beetle he pinched it up. He was offered a jar by a slave. With his free hand he broke its seal, ran the robe glyph round inside, then began to carefully anoint one of the shoes upon his lap with the pungent wax.

Carnelian found that his robe had the same glyph. He could not read it. Everything he had seen his father do he did as well. Several times he looked up to find the eyeslits of his father's mask angled towards him. A nod came from it when Carnelian was finished.

The Chosen shall not breathe unhallowed air,' the quaestor said.

The Masters gave the response.

Slaves with strange bright eyes came cradling bowls. They took tiny steps, afraid of spilling what they carried. As one came closer Carnelian saw fumes curling up from the bowl like smoke. He saw also the spiralled plaques that served the slave for eyes. Edge hooks gripped them into the man's flesh.

Carnelian's father nudged him. He turned to see his father laying his mask face down along the hollow between his thighs. He reached out, took one of the linen pads draped over the bowl's rim, dipped it into the vaporous liquid, and pressed it over the mask's nostril holes. He swivelled little flanges to hold it in place.

Carnelian began the procedure. As he leant forward the vapour from the bowl stung his eyes. He dipped a pad, squeezed it, poked it into his mask still smoking then secured it with the flanges.

'It will protect you from the plague,' his father's voice rustled in his ear.

Then the quaestor spoke one last time. The Chosen shall not be touched by unhallowed light even unto the skin of the smallest finger.' His hands dropped, the cord dangling in the left one.

At that signal, Aurum rose up to all his imposing height holding his mask in one hand, his ranga shoes in the other. Walking off towards an archway, he disappeared through it.

They waited. A blinded slave appeared in the archway. He looked small, fragile. Carnelian felt his father getting up. He watched his hand dart, As the youngest, you must follow last. Then he too crossed the chamber to the waiting arch.

So it was that one by one the Masters were swallowed by the arch till Carnelian was left alone with the quaestor and his spiral eyes. He averted his face from the fumes rising from his mask and looked at the quaestor uneasily. The man was like something not alive.

A muttering came from beyond the arch. Suddenly Carnelian saw the slave was there. He rose, walked to the arch and, after a moment's hesitation, passed under it.

Almost night. Vague sinuous movements like windows reflecting on dark water. Nudges guided Carnelian through the gloom. Fingers plucked at the hooks down his back. The robe brushed away leaving him naked. Shapes solidified into men: yellow men, with dark whiteless eyes. Carnelian swallowed past the dry lump in his throat knowing he was wholly in their hands.

His fingers were prised open and his shoes and mask removed. He shuddered at the first cold touch on his arm. A melting snowflake. Then another and another, till he was the centre of a blizzard of menthol swabbing.

Cool hands lifted one of his feet. He felt the wetness lick between his toes. Then it oozed along the sole. A palm cupped his heel and guided his foot down. Before it reached the floor it hit something solid. One of the ranga shoes. When the other foot was cleansed Carnelian climbed onto the second shoe.

He noticed the depression in the brass wall. It was as if a stiff-limbed man had detached from the wall leaving behind his impression in the metal. The concave surfaces within this mould were as ridged and whorled as finger ends. As he watched, one of the black-eyed men reached into the shoulder of the mould and running his fingers delicately round the hollow came back and transferred its designs to Carnelian's own shoulder. He squirmed at the tickle touch of the stylus. Others were reading the mould. Soon, ink was itching over every part of Carnelian's skin until only his face was left blank.

That His servants might pass you by,' one whispered.

Then Carnelian was glazed with sickly myrrh.

That His breath might not corrupt your flesh.'

Cloth bands darted through the air and spooled around his body.

That His servants might be confounded.'

The bandages stuck to the glaze, weaving into a tightening cocoon.

That they might be lost in this labyrinth.'

He grimaced as a bandage bound something hard and cold against his skin.

'Charms to shield you from their malice.'

So it went on. He was the axis of their strange dance. Round and round they went, their whispers in his ears, until he dizzied and almost swooned.

When they stopped turning he fought the tightness round his chest and shoulder to raise his arms. His hands were there at the end of his cloth wrists. He let them fall and sighed with relief at the pressure release.

A huge robe flapped over him.

That they might be blinded by the night.'

Hands flitted over the robe till it was hugging him. They shut him in behind his mask. His nostrils burned, then his lungs. His eyes watered. He did not even try to move until the burning had abated. Then he tottered out of the brass chamber by a doorway that appeared as a fuzzy glowing rectangle.

'Here you are permitted to remove your mask,' his father said.

Carnelian did so with some relief. His eyes still watered and he was sniffing.

His father put a hand on his shoulder. Its whiteness was spotted with symbols. The astringency will soon diminish, then you will bear it easily enough.'

'And the tightness?'

The bandages will stretch.'

Carnelian heard Aurum say something about an 'imminent departure'.

Carnelian grimaced through his tears. The Three Lands at last.'

His father smiled grimly. The Three Lands.'

'I must make sure our people are ready: Keal, the tyadra, the baggage. How much time is there, my Lord, before we all leave?'

His father's hand jabbed a sharp negation. 'Surely you had understood that they are not to come with us?'

'My Lord?'

They are an encumbrance we cannot risk. Their faces proclaim who we are.'

Carnelian felt sick. 'But I gave assurances.'

His father's eyes narrowed. 'Which you should not have given.'

Carnelian opened his mouth to say more.

His father's hand flew up, Enough! 'Whatever it is that you have said it is my will to overrule. You may take Tain because he does not yet bear our mark. What little state you are allowed, he will keep.'

'Will he be safe?'

His father looked at him, confused. 'What?' His hand made a vague gesture. 'As safe as you or I.'

Jaspar came towards them, his ranga and bandaged legs lending him the gait of someone wading through water. He pursed his lips. 'One fears this journey will be exceedingly tedious.'

Vennel raised his voice behind them. All four Masters turned to listen to him. 'I shall go to make sure my household have made the preparations I commanded.'

There is no time for that, my Lord,' Aurum said quickly.

Jaspar moved off towards them. 'We must hold a conclave ere we leave this tower, Vennel.'

Suth turned to join them, but Carnelian reached up to touch his arm. His father turned back. 'What is it?'

Carnelian could see the irritation in his face. 'Might I be permitted enough time to return to the household to bid them all farewell?'

His father frowned.

'And to ensure all arrangements properly made?' Carnelian added.

The other Masters were now involved in some kind of argument.

'If you must,' his father snapped. 'But do not dally. A guide will be there to bring our baggage to the gate. Let him lead you. I shall be going there immediately…' He looked over to the others.'… with the other Lords.'

Carnelian walked as quickly as his ranga shoes would allow. Each step clattered echoes round the hall. When he reached their door the banners of House Suth no longer flanked it. He was wondering if he had come to the wrong one when he heard muffled voices. He flung his weight against the door. It gave way slowly, heavily. As he squeezed through the opening he trod on something and bent to pick it up. It was an iris, crushed, its bruised purple skin dusted with its own pollen.

Running up towards him, Tain stopped to look him up and down, no doubt startled by the strange clothes and the ranga shoes. Thank the Gods you've come, Carnie.'

He cast a quick, unhappy look around him. People were wrapping vases in the blue canopies. Someone cried, The Master.' People dropped to the ground. A cloth came loose and wriggled down to the floor. Among them a single figure was left standing. It was Keal, his look so intense that Carnelian almost dropped his gaze. He felt shamed.

'You're not going,' he said in a thin voice. It was difficult to squeeze the words out; his throat seemed to have narrowed. People were looking up at him from their prostrations. Everywhere he saw their bewildered eyes. Anger surged in him. He lumbered forward and slapped a stack of boxes. They crunched to the floor. A bowl rolled and shattered. 'Why are you packing? You must all be stupid. You're not going, I tell you.'

'We're being moved into the slave pens,' said Keal. 'When the arrangements have been made we'll be setting off after you along the road.'

Carnelian noticed a man's back wearing the Legate's green. The stranger was the only one still prostrate. 'You!' he shouted. The man trembled. 'Yes, I'm talking to you.' The man looked up. The Legate's sign marred his face like a birthmark. Carnelian pointed at him. 'Get out and wait for me outside.' The man stumbled to his feet and cringed past Carnelian, who watched him slip out between the doors before turning back to his people.

Keal's eyes, Tain's eyes, so many eyes.

Carnelian removed his mask and bowed his head a little, giving in to its heaviness. 'I did what I could. I can't see what more you could expect of me.'

Keal nodded, but did not stop looking at him with pain in his face and something like an accusation of betrayal.