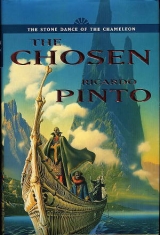

Текст книги "The Chosen"

Автор книги: Ricardo Pinto

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 18 (всего у книги 38 страниц)

As the Marula thrust a way into each new current they looked back with questioning faces. Each time Aurum shook his shrouded head. At last they came to where a river of people was flowing along a black paved road. Aurum gave a nod and the Marula led them in.

Carnelian reeled in his father's aquar while all the time searching for enemies. They were in a soup at a rolling boil. Faces, hand-clasped bags and sacks and pouches, fruit-filled baskets, bubbled in and out of sight. Mottled beasts, some with feathers, some without, panniered, loaded, yoked to wagons, to chariots or swinging palanquins like soft humps. Painted eunuchs, women in gaggles, swaying on carried chairs, swollen with child, their menfolk trying to make way for their bellies. Toll-keepers rode through like lords at a fair. Merchants marshalled their caravans with whips and bellowing. Urchins ran weaving, screaming, playing hide and seek among the angling thickets of legs. The roar never ceased. The air was never free of the brisde of poles, the slap and billow of canopies, of swagging ropes. The ground rarely showed its slimy mush of peelings and feathers, of flowers and dung.

Tortuously, they worked their way round the Wheel on the black road and then, abrupdy, turned in towards its centre to climb a wide ramp. Through a gap in the crowd, Carnelian saw a snatch of its balustrade where an old woman sat amongst a rot of melon rinds, offering up trinkets, her toothless grin tracking passers-by.

At the summit of the ramp a roar of water drowned out the crowds. Over the balustrade Carnelian saw a wide channel thrashing white, rushing water round in a wide arc. The water spilled out from the channel all along its length into cisterns mobbed by people.

When he looked up he realized the whole vast mosaic of the Wheel was laid out around him. He twisted to look back. The gatehouses they had come through now looked smaller than his hand. Behind them was the irregular rim wall. He followed that round and found another pair of gatehouses at a greater distance, then round to another pair further still, and to where yet another gateway touched the edge of the canyon's mouth. Across on the canyon's other side he found one more gate that closed the ring. The quincunx cypher made sense to him. Not counting the way into the canyon, the Wheel had five gates in all.

The shadow of the Sacred Wall was still dulling colours over half the Wheel. Where the sun had reached, delicate patchwork stretched its hues off towards the moat. Far away it was stitched together from tiny lozenges, closer it resolved into neat rows of vendors sitting among their baskets and their blankets, green-heaped with herbs, and all manner of vegetables and fruit. Dark cuttings toothed the Wheel's rim showing where channels cut into it from the moat. A ring shearing in the human flow showed the road they had left. Inside that, the water channel and its cisterns formed a glittering circle. Six ramps crossed this. Five of them lay on one of the spokes that led to a pair of gatehouses. The sixth led to bridges over the moat and on into the canyon and the crater of Osrakum.

As they descended into the inner Wheel, Carnelian was beginning to believe they had managed to elude their attackers. He could hear music. Flags proclaimed the trades of the bonesmith, the featherer, the copper-beater. The weavers were there with their cottons, the pigmenters with their dyes. Lacquered boxes rather than baskets held every kind of precious commodity. One man was rolling out leathers rippled like water and another displaying cylinders of ivory as thick as his arms. Among them strolled buyers, their face tattoos proclaiming them the servants of the Masters. Behind them swung chests with their treasure of coined bronze.

The music of horns and cymbals was coming from somewhere up ahead. Carnelian tried to see round the riders blocking his view. They were nearing the ring of poles that he had seen from the ramp defining the hub of the Wheel. From each pole hung strange fruit. The fetor of decay swelled with the carnival music. Carnelian could see dancers cavorting between the poles, snaking yellow ribbons through the air. People were poking sticks into the things hanging from the poles. Squinting, he was appalled to see that they were men dangling in the air spread-eagled on diagonal crosses. As he came closer, Carnelian flinched away from one man's agonized face. A hawker was selling makeshift spears to his tormentors. Carnelian had to pass so close to the crucified man that he could smell his sweat and the excrement that streaked his legs.

The Wheel's hub was fenced in by these crucifixions. Carnelian was looking round in disgust when his aquar began to be jostled. The crowd was milling. One Maruli's aquar was shoved into his. Angry voices were drowning out the horns. His aquar's plumes flared. Carnelian pulled his father's saddle-chair as close as he could, then stretched over to grab its rim. His father jigged like a sack. A surge was rushing towards them across the mass of heads. It struck. Although Carnelian was almost unseated, he still managed to keep hold of his father's chair. Aurum's voice was shouting commands over the riot. Carnelian watched the Marula stabbing at faces with their lances. Panic was ripping gaps in the crowd as Carnelian watched hands reach up to one Maruli's saddle-chair. The man had a sword out and was chopping at them. For each hand that was stung away two more grabbed hold. The chair was toppling. The aquar was struggling against the bodies pressing round it. Suddenly the Maruli was yanked into a surf of hands and disappeared. For a moment he resurfaced, bloodied, then the crowd closed over him. Carnelian looked round in shock and saw another Maruli being dragged to his death. He tried to edge his aquar and his father's round to shield him. His own chair lurched suddenly to the left. Hands were grasping the rim. His father's chair bobbed free as Carnelian was forced to let it go. Faces grimaced up at him as he fumbled for one of his ranga shoes. He stamped at their fingers and heard bones crack but still they clung on.

Master voices crying out in wrath made Carnelian look up. They were revealing themselves, huge and golden-faced. He pushed his own hood back. Instantly most of the hands released their grip as if his mask were shooting flames at them. His chair righted a little, but fingers still gripped like grappling hooks. The faces over the rim showed doubt as round them the crowd was falling to its knees. Still they pulled, gnashing their teeth as he struck repeatedly. His chair's lean was increasing. Soon he would fall out. He could see enraged men waiting below with their flint knives.

A voice boomed so loud it made the crowd seem quiet. 'Brothers of the Wheel.' The assassins looking up at Carnelian faltered. He was jolted to one side as his saddle-chair was released. He looked round and saw the gold-faced figure sitting tall in his father's saddle-chair. 'I am the voice of the Masters.'

Carnelian stopped breathing. His father had come back to life. The crowd stilled.

The Mountain knows who you are, Oh Brothers of the Wheel, and what

… you do here… today. Slip… slip…' His father crumpled.

A voice could be heard giving commands in thin Quya but Carnelian could see the blood lust returning to the eyes below. Fingers curled slowly over his chair's rim. Carnelian watched them, his ranga shoe held high. He allowed his arm to sink and put the shoe across his knees. He lengthened his back, lifted his chin. He moistened his lips. 'Slip away.' He felt his mask quivering with the words. 'Slip away, Oh Brothers of the Wheel.' His voice was finding its strength. 'Slip away now and this sin'll be forgiven you.' He felt the power. He was a spindle of iron. He raised his hand to point up at the sky. 'Persist and you may be certain that as surely as that sun'll set tonight, so shall the vengeance of the Masters find you to exterminate you root and branch even to the remotest of your kin.'

His words had turned the crowd to stone. A lone voice warbled a command. Carnelian saw his attackers fleeing, chasing the ripple of prostration that was spreading away through the crowd. Around him the marketplace might have been a plain of ferns flattened by a whirlwind. A murmur came from those distant parts of the Wheel that the silence had not reached. As Carnelian looked round he felt the power drain away. An aquar was wandering with what was left of his father crumpled in its saddle-chair. The moaning of the crucified was a wind through winter trees.

THE THREE GATES

Three lands

Three gates

And three tall crowns

(nursery rhyme)

'Suth has killed himself,' shrilled Vennel.

Jaspar's mask was surveying the further reaches of the crowd. 'I had thought him already dead.'

Aurum rode to stoop towards Suth's cloak.

Vennel looked at Carnelian. 'Grieve not, my Lord, your father's death was not in vain. He saved us and now you are the Ruling Lord Suth.'

The reins sagged in Carnelian's hand. His aquar began ambling.

Jaspar looked round. 'We must haste to the gates. This is no place to linger.'

Carnelian felt as if he were bobbing in icy water.

'He yet lives.'

They all turned to Aurum.

'He lives, you say?' cried Vennel. 'Are you sure?' Aurum straightened. Though his blood grows cold.' Carnelian yanked his aquar back into control and moved to his father's side. He reached over to touch him. His father's cloak could have been stuffed with clay. No sound of breathing came from behind his mask. Carnelian rummaged among the cloak's folds for a hand. He lifted the lank flesh and placed his finger to the blue cord bridging the wrist. There was a flutter like a taper flame. He sighed and stroked it, before replacing it in the folds. He felt a shadow fall on him and looked up. It was Jaspar.

'Are we safe?'

Aurum's mask seemed to melt and flame as he nodded. The danger has passed for now. Her web is torn a second time.'

'And the Marula?'

The crowd's tide had crept away, stranding the corpses of three of the black men in their puddling blood. Aurum ignored the question and began barking commands at those still alive. Carnelian's eyes lingered on their pinched faces. They seemed not to have heard. Their red eyes slid sidelong to their fallen comrades.

'On, I say, on!' cried Aurum.

Marula eyes glanced off the mirror of the Master's face to stare up to the faces of the Gods sneering down at them from the canyon's throat.

Aurum swept his hand around his head like a blade to indicate the encircling crucifixions. 'If you don't want to end this day hanging on a cross, you'll move on.'

The Marula hunched reluctant, then first one and then the rest urged their aquar forward towards the prostrate edge of the crowd. Their lances stiffened as they coughed battle cries and began to pick up speed. There was a screaming scramble as people splashed out of their way like water at a ford.

Aurum looked over at Carnelian. 'Come, my Lord.'

Carnelian tied his father's aquar to his saddle-chair, then, with a lash of his reins, he crashed after the Marula, pulling his father and the other Masters in his wake.

The feet of the colossus appalled the Marula. Great wedges of scabrous stone. Toenails like the roofs of houses. An instep that was a cave. Each foot narrowed up several storeys to an ankle thicker than the gatehouses of the Wheel. The legs barrelled up their leprous towers, leaning towards each other, swelling towards the knees that were bending the mountainous thighs towards them. They shuddered imagining the kneeling avalanche of so much stone. The waist and belly seemed a more remote and solid part of the mountain. A fist supported an arm that in turn buttressed the slab of a shoulder. Strangely, the head looked no bigger than a human head. The head of the other colossus leaned close as if they might be talking together, oblivious of the ant world milling at their feet. The eyes of the Marula were forced to scale further up the Sacred Wall. Crag piled on crag up the slope. The whole skyful of rock leaned out as the canyon walls came together. The black men stared unblinking at the narrow ribbon of blue nipped between them. It was like tottering on the edge of an abyss in whose remote depths a brilliant river ran. They could imagine falling. They screwed their eyes closed, dropped their heads, dizzy, their nails gouging a grip on the rims of their saddle-chairs.

Wind acrid with smoke blew hard against Carnelian's mask. He felt his aquar slowing. He could make out that the ramp he had been riding up from the canyon floor ended abruptly in a promontory. His aquar's narrow head angled up and back, flaring plumes, as he yanked it to a halt. The plume fans folded and he saw the gloomy nave of the canyon. Its slope milled with traffic. Far above, the sky was an improbable painted ceiling.

The scrape of claws made him turn to see the Masters sweeping up with Aurum at their head.

'I will take responsibility for the Lord Suth.'

'You will not,' Carnelian said.

Aurum came very close to tower over him. Carnelian straightened his back and faced him. Aurum flicked the air in anger and turned his aquar, bellowing commands that sent the Marula hurtling past onto the road grooving off along the left-hand canyon wall.

Jaspar came up. 'Why have we stopped, my Lords?'

The Marula are the danger now,' said Aurum, the eye-slits of his mask following the black men as they grew smaller and smaller in the groove road.

Carnelian glanced up the length of the canyon. The sound of water made him look down to see the canal. 'A river,' his voice said.

Jaspar snorted. The vermin in the city below call it the River of Paradise. We call it the Cloaca. It is the sewer of our hidden land.'

'We ride to the Green Gate.' Aurum left the words behind as he launched into motion, leaving Carnelian and the other Masters to chase after him.

Rock was hurtling past his head. The canyon narrowed into the distance where, in a gloomy haze, it turned abruptly southwards. All the way to this bend, the floor was a dusky swirl of wagons and people divided in two by the groove of the Cloaca. A scraping scuffling shook up the canyon walls and set Carnelian's teeth to grinding. In the wind, his cloak became like a trapped bird struggling to escape. Up ahead Carnelian glimpsed the bladed edges of the canyon reaching high enough to graze the sun. It seemed impossible that any light should ever find its way down to the floor.

As they sped round the canyon's bend, Car n elian watched the next stretch coming into view. Billows of smoke rolling towards them engulfed the Marula, then broke over Carnelian till he was riding blind. He choked on the grey air. The clouds thinned enough to show the insect crowds below. Coughing, eyes welling, he tried to peer through the murk. He swam out spluttering as the smoke dispersed like morning mist. They had come to the prickling edge of what seemed to be an impenetrable forest.

The Green Gate, at last,' cried Jaspar.

Staring at the forest, Carnelian realized it was made of bronze, a bladed hedge shaped into a fortress wall that filled the canyon from side to side. The canyon floor was striped and chevroned with wagons covering these patterns in ordered files. Along its centre, the Cloaca had sunk into a chasm spanned by bridges.

Carnelian could see no way through the bronze hedge. Tall banners burned red among the thorns. Other flames appeared and became figures shrouded in vermilion. Some were as small as children. All were enveloped in cloaks that brushed the ground.

As Aurum's mask looked back, Carnelian followed its gaze. The Master was studying the Marula who had fallen behind them in close escort. Their faces were wooden with fear. Mouths hung open as if they were panting. Their eyes fixed on their hands. Tain was there between the legs of a Maruli, slight, unblinking, like a doll.

Dread began stirring in the pit of Carnelian's stomach as he watched the vermilion figures forming into a crescent. He looked at their faces. Each was the same, each divided, half skin, half black. He drew back into his chair as they threw back their cloaks. All wore gold legionary collars. Their leather armour was baroquely textured on the same side as their faces were black and on the other side as smooth as their skin. On each chest was a red flower like a flame. Each man's right side look charred, the left of each was barbarian brown.

'Ichorians,' he breathed. All his life, he had heard tales about these half-tattooed men. The Red Ichorians, guardians of the Three Gates.

One of them stepped forward lightly, like a dancer. He stood smiling before Aurum's aquar and then performed an elegant prostration.

'Surely you are Masters,' the man said, rising to his knees, 'though you wear no cyphers, no banners, nor are you guarded by tyadra. And those,' the Ichorian stabbed his black-tattooed hand towards the Marula, 'those creatures defile this road.'

Aurum pulled back his cowl to reveal the mask beneath and as he did so all the Ichorians knelt except the one in front of him who rose, still smiling.

'You're correct, Ichorian, in all you say,' Aurum said. 'We've come far through many perils and have had need of these disguises. Now we'll happily discard them.'

'We've heard that a party such as this accompanies the Master, Our-father-who-goes-before?'

Aurum lifted his hand in the affirmative and the Ichorian searched eagerly among the shrouded Masters. 'We expected you on the leftway, my Masters. Are you desirous to pass swiftly through the Three?'

Aurum repeated the affirming gesture. 'But first there's one matter you must attend to, centurion of the Red Lily.'

There was a clack as two Marula chairs struck together. Aurum's mask turned slightly to one side as if he were listening for more collisions.

'We aren't yours to command, my Master, unless you wear the Pomegranate Ring.'

In answer Aurum pushed his white hand out of his sleeve and splayed it. The ring was a huge wound in the heart of his palm.

'Father,' the Ichorian cried and fell before him onto the pavement. The cry was taken up by the other Ichorians. The centurion rose up again to his knees. 'Forgive the children that didn't know their father.'

Aurum turned his aquar so that he was looking back at the Marula. Carnelian followed his lead. Hunched in their saddle-chairs, the black men were huddling their beasts together. One of them who dared to look up had the shy look of a child expecting punishment.

Aurum lifted his hand and pointed. 'Destroy those animals.'

'Destroy them,' chorused Vennel and Jaspar.

As one, the crescent of Ichorians swept forward, passing quickly between the Masters to face the Marula. The black men's faces creased with panic. One of the guardsmen lifted his tattooed hand. In his grip was a bird of bronze winged with blades. He released it into whistling flight around his hand. As he let out its leash its blurring circle widened with the eyes of the Marula. Their lances wavered out in front of them as they backed their beasts away. The bladed bird began to keen. Other Ichorian arms were whirling similar weapons. Their keening modulated together into an eerie discordant chorus. The Marula began raggedly wailing as the first blade hurtled through the air. A Maruli slapped into the back of his chair, the blade deep in his throat. His lance angled lifeless. The line that held the blade yanked back and the Maruli's head lolled forward, bounced on the dead man's knees and thudded to the ground arcing blood. The air was sliced by more blade flights. The Marula ducked frantically but there was no place to hide. The aquar made cries like tearing metal, their flaring plumes were scythed like flowers. A hand flew off that was being held up as a shield. Screams were choked to gurgling. Carnelian looked down with horror and saw heads thudding to the ground like overripe fruit, rolling red trails. When he looked up, the headless trunks were jerking as the aquar milled bleating, blood welling in their saddle-chairs and spilling down their flanks.

Carnelian remembered Tain with a gasp. Quickly untying his father's reins from his saddle-chair, he threw them over to Jaspar and then forced his aquar into the maelstrom. Warning cries from the other Masters seemed remote. Everything was moving as slowly as curling smoke. As he ground his eyes round, Carnelian saw one of the Ichorians, only a boy, tugging twice on a line; it bellied back dragging its blade. Blood flicking off it across Carnelian's hand was pleasantly warm. His aquar's steps pumped him lazily up and down. He saw Tain sitting stiff and bloody, eyes screwed shut, clamped in the arms of a headless black and red man. An Ichorian placed himself in Carnelian's path mouthing something. Carnelian urged his aquar on and watched the man jump out of his way. He lifted his gaze, saw Tain, leaned precariously out and prised him from the corpse. As he fell back into his saddle-chair, his brother's weight crushed out a grunt.

'My Lord! Carnelian!' Aurum's outrage blared.

Carnelian looked down into his brother's face, felt him for wounds, prised a reddened eyelid open. His brother's dark eye rolled to white. 'Carnie,' he gulped and burrowed his head into Carnelian's armpit.

Carnelian turned his aquar to face Aurum and the others.

'What in the thousand names of They do you think you are doing?' Aurum boomed. 'You could have been slain.'

The golden frieze of the Masters' faces were judging him. He ignored them, hugged Tain tighter and pushed his aquar through their line. He rode towards the hedge's thick twisting thicket of thrusting bronze. A vinegar odour reeked off its mossy rust. Carnelian's eyes became trapped in all that curving and wandered lost. He found he was looking up through its bristling where his gaze had found the top. A vast height of canyon wall rose to a faraway sky.

He dropped his head into Tain's warmth, rocking him, crooning so that neither of them heard the hedge clank its thorns as it began to open up in front of them.

When Carnelian lifted his head, he saw silver faces floating in the gloom. Lamps glowing like stars lent vague substance to the walls. Masters' masks streaked with their reflections. Looking round, Carnelian could not locate the doorway they had come through. Tain stirred against his chest as if awaking. Carnelian felt him stiffen as ammonites drifted near. Carnelian tried to make his aquar back away but one of them touched a hand to the creature's neck and it sank down.

'Give the slave to us, Seraph,' one of the ammonites said in Quya.

Carnelian clutched Tain.

Ranga shoes clacked towards them.

'You must give them the boy, my Lord.'

Carnelian turned on Jaspar. 'Curse you, I paid your price.'

Jaspar backed away. 'Calm yourself, cousin.' He looked round to see if any of the other Masters were paying attention. The boy's eyes are safe, but he must pass through the quarantine with the others.' He pointed. 'Look, my Lord, we are all handing them over.'

Carnelian looked and saw Jaspar's pallid blood-smeared boy creeping into the waiting hands of an ammonite. He turned back to Jaspar. 'How long?'

'Before he is returned to you?'

Carnelian nodded.

Thirty-three days.'

'A month,' Carnelian cried in disbelief.

Twenty cells lie between here and the Blood Gate and there are another thirteen beyond. He will have to spend a day in each before he is allowed to pass through the Black Gate.'

'Promise me on your blood that he will not be harmed.'

Jaspar shrugged. 'My Lord cannot expect one to vouch for everything. If the child is found to have plague…' The Master put his wrists together in a sign of powerless-ness.

'He does not,' said Carnelian, more emphatically than he felt. He nudged Tain. 'Come on, we must talk,' he said in Vulgate.

Tain clambered over the edge of the saddle-chair. Carnelian fumbled on his ranga shoes and then climbed out beside him. He waved the ammonites back and walked a little way from the others, beckoning Tain to follow.

He looked down at his brother. Carnelian could see his own bloody hand-print on his brother's face. He touched his mask. 'I wish I could remove this thing.'

Tain looked back at him with huge bruise-rimmed eyes.

Tain, you'll have to go with them.' His brother looked fearfully back at the ammonites. 'Will they let me come back… back to you and the Master once… once… once they've blinded me?'

Carnelian threw his head back and moaned. 'Oh, no, no, Tain, it's not that. It's been sorted out. It's not that.'

Tain was still gazing at him.

'No, really, I promise, I swear on my blood, your eyes are in no danger, but…' 'But…?'

'You must be kept apart from us for a month until they're' – Carnelian indicated the ammonites – 'sure that you're clean of plague.'

'Plague,' nodded Tain.

Carnelian noticed the ammonites gathering around one of the kneeling aquar. 'Please go with them. I must see to Father. Trust me, Tain.'

'At the end of it, they'll send me to where you are, Carnie?'

'I promise.' Carnelian gave his brother's arm a squeeze. There was nothing to grip but bone. Tain looked stuck to the ground. Carnelian pushed him gently away. 'Go on, pull yourself together, endure it, you're strong enough.' He remembered something. He fished out the Little Mother from a pocket and pressed her into Tain's hand. 'She'll look after you.'

Tain gave a watery smile and hid her in his fist. Carnelian watched him turn, hesitate looking at the ammonites with their sinister silver faces, then pace towards them. Carnelian turned away and strode off towards his father.

Ammonites were crowding him. Aurum was standing looking in over their heads. Carnelian heard the tearing sound. He pushed through them and saw they were ripping through his father's cloak like a crab's shell to expose the yellow-white body inside. One of the silver masks leant so close that it caught a twisting reflection of the wound-stained bandages.

The creature straightened up and looked round at the gold masks. 'Seraphim, these bandages have been tampered with.'

Aurum leaned over to see. 'Perhaps his slave…'

The ammonite whisked round, looking off towards the boys who were undressing. 'Which is he? He must be destroyed.'

'It is too late for that; he was one of the Lord Aurum's numerous victims,' said Carnelian bitterly.

Aurum's mask looked down at him from a height.

'Besides,' Carnelian continued, 'it was I who cut the bandages.'

'Indeed, my Lord,' said Aurum. 'Now we see why he is dying.'

Carnelian flared up. 'How dare you accuse me of that? I did it with his agreement. The bandages were rotting…'

The Law-'

'Does my Lord speak of the same Law which he has seen fit to break at his every whim?'

Aurum's mask angled a little to one side. This impertinence-'

'Are you then, my Lord, He-who-goes-before? You must be since you wear his ring.'

The boy makes a hit, my Lord, a palpable hit,' said Vennel gleefully.

'I think, Lord Aurum,' said Carnelian, 'it would be better if the ring was returned to him to whom it legally belongs.'

Aurum seemed to grow taller, more menacing. The Law must be obeyed,' said the ammonite. 'I merely borrowed it to protect He-who-goes-before when he could not protect himself,' grated Aurum. He put his hand out and opened it to reveal the muted flame of the Pomegranate Ring.

Carnelian reached out and took it. The ammonite began to protest, but stopped when Carnelian lifted his father's hand, threaded the heavy ring onto the middle finger and closed the hand around the gem.

Vennel turned to the ammonite. This matter will have to be reported to your masters.'

'Perhaps, before he does that, he should first attempt to save the Ruling Lord Suth's life, or would you both rather have him die,' said Aurum icily.

Vennel pulled back like a snake ready to strike.

The ammonite lifted his hands. 'Seraphim, this behaviour is unworthy of your blood.'

'His life, ammonite…' hissed Aurum.

'It… this wound, it is beyond my skill, Seraph. Only my masters can save him.'

Then, ammonite, do you not agree that we had better make haste to get him to your masters? I promise you, your skin will not long remain your own if they find that you have let him die.'

Ammonites led them up a flight of stairs to a hall where the Masters were divested of their riding cloaks. Their long slim bodies were revealed wrapped in bandages sweat-stained yellow. New ranga were brought and jade-green robes spiralled with ferns. Their old cloaks and ranga shoes were gathered up with tongs and burned in a brazier.

As Carnelian came back down, he clenched and unclenched his hands that were sticky with Marula blood. He watched his father being moved to a bier and then covered with one of the green robes. Tain was a little way off, naked with the other boys, just skin stretched over bones. His head was in the grip of an ammonite being turned this way and that as the ammonite's silver mask peered at him. His shoulders and back were painfully bruised. Carnelian could guess by whom. Another boy whimpered as he was folded for examination. Carnelian turned away, knowing he had to let his brother go.

As a bright rectangle opened in the further wall, Carnelian strode after his father's bier. The green silk was heavy as he lifted it with his knees. The new ranga were taller than the old ones. He had to swing his feet. It was like walking on stilts.

He clacked out onto the road with the other Masters. The air had grown hot. Amid kneeling rows of Ichorians were chariots like jewel boxes. His father was being carried to one whose wheel rims rose above the heads of the people round it. Carnelian followed. The back of the chariot was a dull mirror of gold from which a Master was surfacing as if from a bath. Ammonites reached up to the handles with hooks and halved the Master by pulling open the doors. Others lifted the bier, rested its edge on the chariot floor, then, careful to touch nothing, fed his father in feet first.

Carnelian watched Jaspar climbing into another chariot nearby. He saw that it was yoked to a pair of pale-skinned aquar. Naked half-coloured men held their halters.