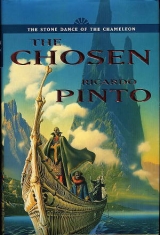

Текст книги "The Chosen"

Автор книги: Ricardo Pinto

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 31 (всего у книги 38 страниц)

FORBIDDEN FRUIT

Clutch my warmth

Until day comes

For then we must part

(from the poem The Bird in the Cage'by the Lady Akaya)

The raven hopped into the air, flicking open its fan-feather wings. Carnelian tried to catch it, his fingers shredding the air like its black pinions. The other distinct half of him was there without a face, touching the whole surface of his skin. He clenched the anchor grip of their hands but its fingers were squeezing to blood. The raven's eye stared white as an egg. A red tear leaked from the corner with each blink.

'Flee with me away from here,' the raven screeched. Its beak was the pin holding everything together.

But Carnelian would not abandon the faceless half of him. Looking round, he tumbled falling. The red earth caught him. Grit in his eye. Sinking. He struggled to stay perfectly still. Every movement trembled pebbles and scratched his skin deeper in.

'Away from Her.'

The earth brimmed over him like honey round a stone.

Warm pulsing red darkness beating him like a heart. Buried alive. Opening his mouth to scream let dust pour into his stomach, into his lungs. Drop by drop, moisture sucked out of his husk till his organs rattled inside him like seeds.

Carnelian jerked awake to see a creature hovering over him, its wings splayed like hands to grab him.

'What is wrong?' said the creature. Carnelian recognized Osidian. As his friend crouched, Carnelian saw the idol of stone behind him, a winged man, looking as if he had only at that very moment descended from the heavens.

The Black God,' he breathed.

As Osidian looked up, his shoulders relaxed. The Wind Lord.'

Carnelian could not stop staring. The idol's empty eye sockets were terrible. From the left eye, tears dribbled down the stony cheek. 'An avatar of the Black God.'

Osidian shook his head. 'A false Quyan deity. The only true gods are the Twins.' He smiled. 'Besides, our friend here poses no threat. Has he not given us the comfort of his hospitality?'

The comfort…?' Carnelian said, stretching the stiffness from his arms, arching his back. Osidian was gazing towards the light. The narrow shrine with its corbelled vault ended in a triangle of morning so bright it hurt his eyes. Its sloping walls were stiff with the carved wings of wind creatures. Rubbish clotted the floor. 'Do we have to wade back through that?'

'Unless, in the night, my Lord has been gifted with a sprouting of wings,' said Osidian. He made a pantomime of looking for them.

Carnelian slapped the hands away from his shoulders.

Osidian grinned. Carnelian was embarrassed by the look in his eyes.

As they slid down to the floor, the filth oozed up between their toes till it seemed they stood on the stumps of their legs. They exchanged looks of disgust and began to squelch off to the entrance.

When they reached it Carnelian glanced back. The winged god looked like a great raven. He realized something. 'His altar was our bed.'

'You would agree that it was better than the floor,' said Osidian. 'Do you think he begrudged us it?' He did not wait for an answer but walked out into the morning.

Remembering his nightmare, Carnelian looked back into the shrine uneasily, then followed him.

He stopped. At their feet was a tangling, as if a net had been cast over a skyful of birds leaving only their bones and tattered green feathers. Thorn trees,' he said, his voice loud with disappointment. He had expected the Yden to be more lush.

The air tore with screams and something like a shaking of many blankets as the cliff of the Pillar came to pieces round them. He ducked with Osidian as a vast shape wafted over them. He glanced up to see the air screeching with leather kites.

'It seems you have woken our fishy friends,' cried Osidian. 'Come on.'

Half crouching they fled, laughing, down the wide steps crusted white, through a shimmering stink of ammonia and rotted fish. Above them, the creatures circled on fingered wings, slicing the air with their pickaxe heads. Soon the white on the steps was only a splatter, the air cleared, cracks became jagged with weeds.

The trees formed a wall of thorns. Through their knotting branches, the sky was a mosaic of blues. Looking back, Carnelian could see nothing of the steps. Up the cliffs he found the nodules of the sky-saurian nests and perhaps, though he could not really be sure, the Ladder's zigzag. The Pillar soared up to fill the sky. Somewhere up there were the Halls of Thunder.

Carnelian's gaze came back down to earth. Osidian was walking off clothed to the waist in dust clouds. Carnelian followed him, frowning. Here and there an angled paving stone showed where a road lay under the dark earth. Peering into the thorns he saw the cracked carvings running along its edge. The road curved off to the north but Osidian turned off it and ducked into the thicket.

'Hold on,' Carnelian shouted after him.

Osidian's head poked out from the thicket as if from a hut.

Carnelian pointed. The road goes this way.'

Osidian smiled. 'So it does, into the Labyrinth. We, however, go this way.' He pointed into the thicket. 'Be careful of the thorns,' he said with a grin and disappeared again.

Carnelian frowned when he reached the place where he judged Osidian had gone into the thicket. After much squinting, he managed to see him there, moving away through the tangle along something like a tunnel. Carnelian gave the road one last envious glance before ducking in among the thorns.

The tunnel forced Carnelian to bend his back. Thorns snagged his clothes so that he often had to stop to unhitch the cloth. Several times, mockingly, he muttered, 'Be careful of the thorns,' and then growled.

He struggled to catch up with Osidian, wanting to berate him, but when he began Osidian turned and lifted up his hands to show his own red scratches and Carnelian had to give him a grudging smile and close his mouth.

At last they came to a lofty wall. Its massive blocks were irregularly shaped but fitted together with remarkable precision.

'What now?' asked Carnelian, exasperated.

'We climb over,' Osidian replied and slipped sideways along the wall, going down the gradient, in the wedge of space that was free of thorns.

Carnelian followed. Osidian found something like a ladder whose footholds were the edges of blocks. Carnelian watched him climb higher and higher and then, with a vault, he was sitting astride the wall, waving him up-Muttering, Carnelian began the climb. Some handholds he had to stretch for. He missed one, slipped and grazed his arm. Osidian offered him his hand and grinned when it was refused. Carnelian insisted on scrambling his own way up. He made sure he was secure, then turned to Osidian.

'You are-' He fell silent, gaping at the view. Below them was a terrace of black earth divided neatly into plots. Further down the slope there was another terrace and further down from there, another and another, until he had counted almost twenty in all, the most distant of which looked like chequered cloth. Beyond, a forest stretched for a great distance, turning at last into polished jade and then the purpling turquoise of the Skymere.

Osidian touched his shoulder. 'It gets better.'

They slithered down, dropping the last bit into a thick bed of giant cabbages that squeaked and snapped as they fell in among them. The musk of wet earth and the green bruising smell of the leaves filled the air. They clambered out onto a path and wandered along a maze of them, each walled by vegetables. Here and there Carnelian glimpsed a glitter of water running in stone channels. They crossed several by means of little bridges. Every so often the vista would open out and he would see the terraces again.

'A kitchen garden?' he asked at last.

'For the court,' Osidian answered him, pointing at the black craggy cliffs of the Pillar.

As they strolled, Carnelian was filled with wonder. He asked Osidian the names of everything. Osidian always had an answer and even added what he knew of their uses or plucked some for Carnelian to smell or taste.

Carnelian glimpsed movement and found himself scrabbling for his mask. Osidian's hand restrained him.

There is no need, he signed. Here there are no eyes but ours.

They walked out into a clearing in which a number of creatures were harvesting leaves with sickles, or turning the rich black earth with hoes. Carnelian tried to see what kind of beings they were. Nut-brown, with hands and feet like spades, but not tall enough to come up to his knee.

They move as if they had eyes.

The sylven have keen ears and well-honed touch.

They look like little men.

Animals. 'Let me show you,' said Osidian. As he spoke the sylven stopped their work and turned their wizened heads. Osidian clapped his hands. 'Attend me.'

The sylven came, forming round them, their heads bowed, their huge ears sticking up like horns.

Osidian crouched and took one in his hands. The little wizened creature flinched and whimpered. Carnelian began protesting even as Osidian cooed and said, gently, 'You will not be hurt.'

He held the creature's little brown head carefully like a ripe fruit. Carnelian crouched, to stroke it. Osidian angled it back to reveal a tiny face. A wide gashed mouth, a nose flat and splayed. Osidian squeezed apart the wrinkles that closed its eyes. At the bottom of the pit was a colourless bead like the raisin of a pale grape. Osidian let the creature go.

'It seems very much like a tiny man,' said Carnelian.

Osidian shrugged. The world is filled with man-like creatures. What is a man? Are these men? Are the sartlar?'

The barbarians are men.'

'Perhaps, but if so, not like you or me.'

'I suppose, then, that you would claim that we are angels.'

'Is that not what the Wise teach?'

As they wandered further into the garden they saw sylven everywhere like clods of earth. The sun began to pour its fire into the day. They came to a region where each tree was inside the square of a low wall.

'Ahaa,' said Osidian. He leapt onto one of the walls, and reaching up into the branches of its tree he plucked a fruit. He turned and offered Carnelian its red-streaked gold. 'Smell it.'

Carnelian obeyed and closed his eyes as he drew in its perfume. He bit into it. Its flesh was creamier than a peach, filled with seeds that had the flavour of almonds. Osidian beamed at his reaction. Carnelian took another succulent bite. 'Why the wall?'

'It reserves the fruit for those of the House of the Masks.'

Carnelian stared at the forbidden fruit. His sin was there, cut into its flesh. He felt its juices dripping down his chin.

'Who will know?' said Osidian. He took a bite of his own fruit. 'Come on, finish it. Have you ever had a better breakfast?'

Carnelian ate it, quickly, swallowing every last bit of it.

Osidian dramatically widened his eyes. 'Maybe we should consume the whole tree. It might be perilous to leave any evidence.'

Carnelian made a face at him and they both laughed.

The terrace took them round the Pillar until they came at last to another wall in which there was a gate. Through its frame lay another wonder. In the morning shadow of the Pillar of Heaven there were as many terraces but these were arranged in a design so complex that it confused the eye. It seemed to move, rotate, like some fantastic mechanism. The patterns were bewildering and on every scale. The whole glinted darkly, chinked and shimmered.

Osidian was smiling at him, reading his face. He jabbed his thumb back in the direction of the gate. 'My Lord thought that was the Forbidden Garden of the Yden, did he not?'

Carnelian had to admit that he had.

'Well, let me show you the real one,' said Osidian and strode through the gate.

Carnelian joined him, walking by his side. He fingered his mask hanging at his hip. 'Will we come across anyone?'

'Perhaps more sylven but none of the Chosen. This late in the year, we will have the garden to ourselves.'

Carnelian allowed himself to be carried along by the gleaming, iridescing pavements. They wandered down avenues of dragon-blood trees, like upturned brooms, their trunks striped with bands of jasper and carnelian. They dangled their hands in pools in whose green water white, gold-patched carp slid, each larger than a man.

Osidian pointed out their mouths and fins all pierced with silver rings. Other pools had tiny fish that glistened hither and thither like sun flecks on the sea. The pools poured into each other through great spouts, sometimes arching water over their path so that they could feel its flash and mist on their skins. Everywhere the walls were carved into grotesques, grimacing or pouting gargoyles spitting fountains or bristling with trees. A pavilion of salmon-striped green marble tempted them into its murmuring recesses. Steps banistered with cascades led down to the next terrace. They dallied in other pavilions. Those of heart-stone, quarried from the Pillar of Heaven itself, Osidian told him, were rainhalls, their roofs and pillars contrived to convert rain to music. Others had walls so thin they could make out the vague languorous shapes of the trees beyond. In places the air darted with parrots more brilliant than butterflies. Quetzals shuttled emerald between trees. Sawing their cries, peacocks pulled trains of staring feathers.

It was the vast and sombre pillared hill of the Labyrinth that brought them back to earth. Its mound ran along the edge of the terraces, tumbling its frowning facade down into the distance. Where the Labyrinth and the Pillar met, the latter folded into a crevasse that rifled all the way up to its dark and brooding summit. Carnelian searched there and found the jagged line. The Rainbow Stair,' he said.

Osidian appeared to be looking for somewhere to hide. 'We have come too far round. Come on.'

He took them down a stair and another and so they descended the terraces, running for pleasure through the perfumed air. At last they reached the last terrace, which ended at a high glistening wall. They turned to look back.

The garden was a colossal staircase rising up to where the Pillar stood like the Black God Himself, hefting the blue of the sky upon His shoulders.

They explored along the wall until they found a bronze trellised gate through which they could see a shadowy world under the trees. Carnelian was surprised when Osidian produced a key. He thrust it into the centre of the gate, turned it, and then using the weight of his body he swung it open and beckoned Carnelian to go through.

Trunks were spaced like the pillars of a ruined hypostyle hall. Here and there the canopied roof had collapsed into a clearing. They wandered into it as if they were afraid of waking the trees. Scented air encouraged slumber. Soft mulch muffled their steps. Birds flitted across the corners of their vision. Several times they saw saurians, two-legged, as small and curious as children, that when approached slipped away like memories.

This shadowy world was terraced too. Every so often they would descend a shallow stair, then behind them they would see a wall of rough-hewn stones. In some places this had burst allowing the red earth to spill down, revealing the black layers beneath.

They did not talk. Something about the forest encouraged silence. A resinous breeze wafted constantly in their faces. It grew even hotter. Peering ahead, Carnelian had the impression a fire was burning towards them. The tops of the trees around them burst into flame. Light shot over their shoulders from above, growing ever brighter, and suddenly it was stabbing all around them. He turned and saw the shadow of the Pillar of Heaven ebbing away from them as the sun melted up out of its black brow. He was struck by how much it looked like a Master in a court robe.

They walked in the hazing air. It grew torrid, humid, thick with an odour of mouldering. They were by this time following a trickle of water running in the bottom of a crumbling channel. The brightness showed them that the trees were filled with fruit, and it seemed to Carnelian that they walked in an orchard long ago abandoned. Then he noticed the spaces between the trees were all aglitter and he saw, against the band of the Sacred Wall, the blinding sheets of the lagoons stretching to the Skymere.

Osidian clasped his shoulder. 'Behold, the mirrors of the Yden.'

Carnelian watched Osidian sleep in the stultifying heat. Even hiding in the deepest shade they had found no coolness. Through the trees he could see the alluring shimmer of the lagoons. Their glaring silver was animated by the scratches of flamingos wading. There was a lazy buzzing of flies. Everything seemed to be pulsing in time to his slow heart. Osidian had told him that they must wait out the heat of the day. Even with their paint the sun, in the last month of the year, was a danger to their skin.

Carnelian licked his lips, remembering the delicious melting sweetness of the forbidden fruit. He looked up into the branches that were their parasol. The apples there were as brown and wizened as the stony fruits that they had cleared to give them space to lie down. He wanted something filled with juice. He rose, his tunic sticking to his skin. Osidian swatted a fly from his face.

Carnelian pulled one of the purple cloaks from a pack and draped it over his head. Creeping from shadow to shadow, he searched the glowing dappled world for fresh fruit. His skin prickled. He felt the need to scratch himself everywhere. He made sure to look back every so often so as to know where he had left Osidian.

It was the red that drew him to the grove. A low wall ringed it. In many places its stones had tumbled into the weeds and were almost lost from view. Some of the trees had red flowers. He recognized the pomegranates nestling among the waxy green. He jumped the wall and, reaching up, felt the pregnant tautness of the fruit. He plucked one and then another and two more. Their skin was hard but it gave a little when he squeezed.

He returned with his treasures and woke Osidian'. He cut one open and offered half of it to him.

Osidian frowned. 'Where did you get these?'

Carnelian gestured vaguely.

The fruit here are bitter, poisonous.'

Carnelian looked at the pomegranate's womb, melting with juicy rubies. He sniffed it. 'Are you sure?'

'It is forbidden to eat from the trees outside the garden wall.'

'As it was forbidden to eat the golden fruit?' Osidian had to smile.

Carnelian looked into the moist jewelled fruit. He could not resist it. He scooped up some seeds, licked them off his fingers, sucked them free of pulp and spat them out. 'Sweet nectar,' he sighed.

Again, he offered Osidian the pomegranate half. 'I sinned for you.'

Osidian's eyes smouldered like emeralds hidden from the light. He took the pomegranate and slowly bit into its juicy heart.

Osidian awoke him when the shadow of the Sacred Wall had washed over them. He grinned. 'Come on.'

The sky was a cooler blue. Carnelian walked into a clearing and looked back. The Pillar of Heaven was spouting its fiery wall into the sky. He turned to follow Osidian off through the trees.

The ground began to grow soft. He could feel the delicious moisture squeezing out under his feet. He saw a circle of plate-leafed water lily. At its centre a column thrust up from the water flaring into a pink trumpet. More lilies spread their carpet off into the lagoon. Between the shore and the first pad lay a narrow strip of dark water. He saw Osidian hesitating, then in one swift movement leap across. The ridged leaf buckled a little but held. Osidian turned to grin at him. They still bear my weight. I was not sure, but they do.' He leant over to grasp the flowering column and, holding on to this, walked round from pad to pad. He stepped onto another plant further into the lagoon. It was larger and held him more steadily.

Carnelian jumped across. His feet bent a leaf rib like a bow. He followed Osidian, stepping from one pad to the next, the flower stalks waving above his head with each step. Slowly they moved away from the shore. The air cooled delightfully. Up ahead he saw that Osidian had stopped. As he drew closer he saw that the boy was at the edge of the lily pad floor. Beyond, clear unrippled water mirrored the sky. Carnelian reached a pad next to Osidian, who was looking off to the distant Sacred Wall. Its upper edge was still glowing with the sun but its rays were too weak to taint even unpainted skin. Osidian turned to Carnelian.

'You know, I have never even seen the world beyond that wall?'

Carnelian nodded.

Osidian's eyes searched the Sacred Wall as if he were counting its coombs. 'Even those, I can see but never visit.' His jade eyes fell again on Carnelian. 'Is it not paradoxical that the Skymere should be more difficult to cross than your sea?'

Carnelian could think of no answer. Osidian's melancholy left him and he grinned. 'I will teach you to swim.' 'I already know how.'

Osidian looked puzzled, then smiled. 'In the sea?' 'Since I was a child.'

'Last one in is a mud worm,' cried Osidian.

Carnelian watched him as he began to tear off his clothes. For a moment, the flashes of Osidian's cool white skin froze him, but then he yanked off his tunic. When he looked up, Osidian was standing on the pad edge, as naked as a bone spear. Laughing, he cast himself into the water and disappeared. Carnelian was left rocking on his leaf. He watched the ripples fade away and the smashed reflection re-form.

'Osidian,' he cried in alarm, then grinned as the edge of his leaf began folding into the water under the grip of ten white fingers. He tried to keep his balance, but he toppled, crying out, and the water slapped him cool in the face and he felt it envelop his body. He kicked around, found the surface, pushed up through it to gulp at air.

'Mud worm,' he heard, and then a hand on his head pushed him under. He struggled, feeling the vice around his chest, wriggled free, undulated away, opening his eyes and seeing the shadowy shapes, rose to the surface. He gasped air. His trousers clung to his legs. He searched and found the white head floating on the water, looking for him. He emptied his lungs, filled them, then went under. He swam strongly, peering until he found Osidian bright among the reeds. He rammed into his body, clasped it, yanked it downwards, caught the shoulders and, shoving, threw himself backwards onto the surface. He was rewarded by Osidian's startled face erupting out of the water. Seeing Carnelian, Osidian laughed, then sank for another underwater attack. Soon they were wrestling in and out of the water, drinking it, spluttering, until Osidian lifted his hand and cried for a truce.

Carnelian dragged himself up onto a pad and helped Osidian onto the neighbouring one. They lay back over the ribs, still laughing, coughing.

'Who is… a mud… worm?' Carnelian managed to say and the pads trembled with their laughter.

Back on shore they hung Carnelian's trousers up to dry. Carnelian was aware that he was noticing Osidian's smooth body too much and hid his blushes in the twilight.

Osidian pointed. 'You still carry vestiges of your paint.'

Carnelian looked down at his chest and could see a patch dulling the gleam of his skin. He looked up and saw that Osidian too looked like the moon passing behind tatters of cloud. He watched him walk away. His eyes slipped down his tensing and untensing back. Osidian had taint scars only on the father's side. He watched him crouch over one of their packs. Could he be marumaga? No, he had a blood-ring. He watched Osidian rummaging. Perhaps his sybling brother carried their mother's taint on his back. Carnelian decided it was time to ask Osidian who he was. He was coming back, a jar in one hand, a red lacquered box in the other.

'What are those?' Carnelian asked, his question ready, his heart quickening.

Osidian did not answer or look up until he was standing near enough for Carnelian to smell his body. This time he could not hide his blush even though he looked away. Osidian's hand took his face and turned it back. Carnelian watched him kneel down, open the jar, open the box and bring out a pad. He dipped it in the jar and stood up with it. Carnelian looked at the pad held at the ends of his fingers. He looked into Osidian's eyes. They swallowed him. He felt the pad moving towards his face. The sight of it freed him. He snatched Osidian's wrist and held it firmly.

'What're you doing?' he asked in Vulgate, his heart beating hard enough to make him shake.

'Your skin – it's still streaked with paint,' Osidian replied in the same language, smiling tentatively through a frown.

Carnelian shook his head. 'But… you can't. Not you.'

'I want to.' Osidian brought up his other hand to release his wrist softly from Carnelian's grip.

Carnelian let his arm drop. He closed his eyes and flinched as the cool pad touched his forehead. It slid first to one side and then to the other, each time moving further down. Carnelian opened his eyes. He watched Osidian's careful concentration. He closed his eyes as the pad moved into the hollows of his eyes. He opened them again when it moved out over his swelling cheeks and the ridge of his nose. Sometimes, at the end of a stroke, their eyes would meet. Osidian's would gently disengage and he would continue with the cleaning. The pad slipped up and over Carnelian's lip. It came back up and along the hollow between his chin and lower lip. It slid back finding the valley between his lips. Its pressure made them open so that he felt it brushing his teeth and could taste its bitterness. The pad moved away. Osidian came closer till his eyes were all that Carnelian could see: his warm breath all he could feel. He closed his eyes as their lips met and then Osidian's tongue opened them further.

They swam again in the night-black water, slipping like ripples until they found a little stream by its bright gushing. They clambered up over rocks and found a pool. The moon rose to show them the fish darting their silver. At first their attempts to catch them were all splashing, curses and laughter, but eventually they settled down to hunt them slowly, with guile, slipping their hands round them like spoons and scooping them out onto the shore where they beat their shapes into the mud. They took them back, gutted them and ate their flesh raw with more pomegranates and some of the sweet little hri cakes that Osidian had thought to bring.

That night was a wonder of stars. They had made a bed from rushes. Carnelian lay with Osidian in his arms. Osidian's skin touched his all along his side. He moved his head so that he could feel Osidian's breath on his cheek. He gloried in his smell and would have kissed him except that he did not want to disturb his sleep. He propped himself up on an elbow to feast his eyes on moonlight made flesh. Then he lay back, not wishing to drink too much joy. The next day it would be there for him, and the next, and a few days more, and then what? He tried not to think of it. The worry about his father was a dull ache. He clutched Osidian, who moaned and rolled away.

The morning woke them with glorious birdsong. The sun gleamed on the faraway curve of the Sacred Wall. Osidian's kiss on Carnelian's shoulder turned into a bite. Carnelian growled, Osidian ran away laughing to plunge into the lagoon. Carnelian gave chase, dived, came up shrieking from the water's chill, but soon he was pursuing Osidian's flash through the weedy shallows. They played like eels until they saw the fire of the day had reached the edge of the Yden.

They returned, rubbing the water from their skins.

Carnelian stood quietly while Osidian painted him, kissing his hands whenever they came close enough. Afterwards he painted Osidian, caressing him with the brush, their eyes igniting passion.

When the sun grew tyrannous in the arch of the sky, they hid from it, leaning their smooth skin against the rugose bark of trees. Panting, eyes closed, half dreaming under canopying branches, limbs intertwining, they waited for the cooler afternoon.

As the shadows began to spear eastwards they stirred, busting to their shielding paint. They took their bundles and ran, exploring the wilder thickets of the Yden. Pale creatures dressed only in the dappling shadows of leaves, they slipped through the steaming afternoon. Their eyes flashed like dragonflies as they searched out each new wonder. They cast covetous glances on pools and fingers of the flamingo lagoons in which they did not dare to swim lest it should strip away their paint. As the crater darkened they dared to swoop across the water meadows, using lily pads as stepping stones. Then, when the Sacred Wall had washed its shadow over them, they slipped sighing into a pool, burying their flesh in its heavy folds, scrubbing each other free of paint, undulating through the waters that were so filled with fish they could feel their silver against their skin.

At night they ate the food that they had found as they had found it. Fire seemed a sacrilege. They cleaned each other as if it was something they had always done. They made love. They slept together with only the moonlight for a blanket.

The next day they made a raft, and hidden beneath an awning they improvised from their purple cloaks, they paddled among the stilted flamingos to explore the islands lying in the lagoons. On one of these they sheltered from the greatest heat of the day. All day long they heard the waft of birdcalls and the delicate sculling of water as the flocks fed. Stick legs crossed and recrossed like a passing of spears before the scintillating textures of the water.

In the early evening they ran across the mud waving their arms and sending a pink drift up to hide the sky so that they stopped, gaping at the colour and the rushing surge of it.

This must be what it's like to receive Apotheosis,' muttered Osidian.

Seeing the serious, fixed wonder of his face, Carnelian crept away and kicked water over him so that Osidian grew angry and chased him. They wrestled their patterns across the mud and, thrashing, rolled into the shallows. They rose panting, their laughter gashing white their muddy faces. The deepest pool they could find only came up to their waists. They washed each other. Osidian stopped Carnelian when he would have had more play. He seemed remote.