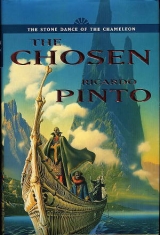

Текст книги "The Chosen"

Автор книги: Ricardo Pinto

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 35 (всего у книги 38 страниц)

'One of the half-black men. He says someone's come to see you and it's very urgent.'

Tain helped him dress and bound on his mask. Carnelian opened the door and looked out.

One of the cohort commanders was there. 'Master, I waited to disturb you till the time you asked me to wake you.'

'What is it?' asked Carnelian.

'A Master from your House needing to see you urgently.' 'Who is he?'

The commander shrugged. 'He came alone.'

'Please bring him to me.' Carnelian closed the door. He asked Tain to help him put on his court robe. Standing on the ranga he watched his brother struggle with the straps and screws. Every time Carnelian tried for intimacy, Tain responded like a slave. Carnelian was kneeling inside his court robe when there was another knocking on the door. It opened when he gave leave and a massive shape slid in. Its gold face looked down at Tain.

Though he does not wear our cypher, my Lord, he is one of ours.'

The Master spent some moments gazing down disdainfully at Tain before he reached up two white hands to remove his mask.

'My Lord Opalid, what a pleasure it is to see you. You have come without your father?' 'I have come alone, my Lord.'

Carnelian raised his eyebrows as the Master fell into silence. 'Well?'

Opalid frowned. 'I was waiting for your minion to finish here so that we might talk alone.'

'My "minion" is more kin to me than you, my Lord, so please tell me what you came to say.'

Opalid looked horrified and stared at Tain as if he were trying to blast him with his eyes. Tain seemed oblivious as he stood on a stool to do up Carnelian's robe.

'Very well,' Opalid said. 'I come, my Lord, on a delicate matter.'

'Indeed?'

'I come to offer your lineage my fealty.'

'It is welcome, my Lord, but this hardly seems to me to constitute an urgent matter.'

Opalid produced some pantomime gestures of distress. 'I came to tell you that my father has betrayed you.'

'Go on.'

'He has pledged his vote to Molochite.'

'Publicly?' Carnelian said, rising, lifting the robe. There was a cry behind him. He had forgotten his brother. He sank down again, saying over his shoulder, 'Sorry, Tain.'

Opalid did not hide his distaste too well. 'How many of your lineage have defected?' Opalid made a shrugging gesture with his hand. 'And you will, I suppose, know nothing about the intentions of the third lineage?' 'Nothing, my Lord.'

Carnelian regarded him silently until the Master could not bear his scrutiny longer, and looked away. 'I will convey to my father your words of loyalty, my Lord.'

Carnelian dismissed the Master and made sure he was escorted out of the Sunhold. Then he and Tain hurried through what remained of the dressing. He did not wish to be late for his meeting with his father.

The Ichorians let Carnelian into the Sun in Splendour. The hall was filled with wind, and dark save for some braziers set in a circle round the dais. In their violent flickering, Carnelian saw two ammonites beside a beadcord chair. Of his father there was no sign.

Carnelian walked towards the ammonites, who knelt as they saw him approaching. 'He-who-goes-before?'

Both creatures pointed off into a corner where Carnelian saw a pale rectangle open in the wall. As he walked towards it the wind beat against him. He reached the doorway and saw that it gave onto a narrow promontory jutting out into the sky. At its tip a glimmering figure was bracing itself upon a post of brass. A cordon of these ran all the way back to where Carnelian stood.

He reached out for the first post and used it to pull himself forward a single step. The wind buffeted him mercilessly. Pulling himself from one to the other he at last managed to reach the figure.

It turned a little and lifted its hand making the signs, My son.

The wind flowed over them. They were like two rocks in a torrent. His father's hand formed, Behold, and then the sign dissolved into pointing. Carnelian saw the indigo vastness of the crater laid out below. They seemed to be standing on the prow of a ship sailing into a dark sea. He could make out the curve of the Sacred Wall, the shore of the Isle, the closed circle of the Plain of Thrones twinkling like a puddle of stars.

Carnelian lifted his hand into his father's view and made the sign, Tributaries?

For answer his father pointed to the Plain of Thrones and then slid his finger out and slowly round. Carnelian saw that it was tracing out a gossamer thread that sparkled like a spider's thread with dew. His father's hand made the signs, They come in, night and day, and then continued round until the thread disappeared into the black gullet of the Valley of the Gate.

The Rains are near and soon, his father's hand pointed back at the Plain of Thrones, we shall go down there for Apotheosis and Rebirth.

Carnelian sieved the wind through his fingers as he prepared himself to give his news. He leaned on the wind to allow him to lift both his hands. Father. Suth looked at the hand. Opalid, Spinel’s son, has just been to tell me that his father has gone over to Ykoriana.

Carnelian watched his father's hands stiffen then sign, Why did he come to tell you this?

I suspect his father sent him to curry favour with us in case the election should go our way.

Suth made a smile with his hand. A childlike stratagem.

Spinel must be very certain of Ykoriana’s victory or else their roles would be reversed.

Fear of my wrath must play its part in his calculations. When you took the Seal from him you left him without means to remove the evidence of his usurpations in the coomb.

How will Ykoriana victorious make any -? Carnelian stopped to think. Could she make him Ruling Lord?

With enough blood and iron everything is possible. The new God Emperor will have much of both.

We are doomed then.

Suth looked at his son. Hold on to your faith, it has become my strength.

But surely if this defection becomes public many others will follow Spinel's lead?

It will become public, that is why Ykoriana has wooed him.

Will that not be disastrous for us?

Not necessarily. If other subsidiary lineages are encouraged to revolt against their Ruling Lords her strategy might well rebound on her since-

Since all Ruling Lords would be threatened and should then be forced to oppose her for their own preservation. Carnelian could see his father nodding and then looking off to where the sky was growing pale.

Suth lifted his hand again, We must move inside and begin our work of masonry.

The ammonite took Carnelian's blood-ring and pressed it into the clay. When he pulled it out Carnelian could see the bead now bore a circle of his name glyphs and the numbers of his taint. The bead the ammonite had made from Nephron's jade seal was the first, Carnelian's was now threaded onto the cord to be the second.

The first two stones in our wall,' his father said.

Carnelian looked up to his father, a golden obelisk on the dais. He looked back and saw the two ammonites sitting beside each other, each with his trays of beads. In front of them a third was sitting with his back to them. All three wore eyeless silver masks.

Carnelian walked round the dais to take his place as witness at his father's right hand. At his feet facing him was a fourth ammonite. Between them was a low table upon which there was an ink sponge and beside it Carnelian's blood-ring. In front of his father a fifth ammonite sat with a table, ink and Nephron's seal. A little further away knelt a sixth. Carnelian could only wonder what his function might be.

His father turned to him. 'Are you ready, Carnelian?'

Carnelian knelt on his ranga. 'As I can be, my Lord.'

The first Masters that were let in were from one of the highest Houses of the Great. Three of them, filled with pride, come to tell He-who-goes-before that they would support him without condition. More followed, with their heraldry wrought in gems upon their smouldering robes.

These are the towers of our new wall,' his father said as they waited for more.

For those Houses that were rich enough already in blood and iron, flesh and treasure soon ran out. It was then that the negotiations began in earnest. Some Houses wanted gifts, blocks of white jade from the eastern mountains, black pearls that had been found in the sea. Sometimes it would be a piece of porcelain a thousand years old or a half-dozen chrysalises containing butterflies recendy discovered, whose wings spanned a shield but would crumple at the merest touch of breath. Suth as Nephron's proxy promised these rarities from the House of the Masks' fabled treasury. Precisely worded, an agreement would be dictated to the two ammonites with the bead trays who would each quickly thread it onto a silver cord. The two cords would then be put, one into each hand of the ammonite who sat before them. Holding his arms out, this ammonite would quickly pass them through his fingers, presumably to determine they were identical. One cord he would then hand back to be added to the lengthening record of which the clay beads were the beginning. The other would be threaded through a hole in the floor. The Masters would wait, making conversation about the Rains, their hopes for beauty among the children in the flesh tithe, their anticipation of pleasure and distraction in the new season's masques. A piece of rolled parchment would emerge from the floor onto which the beadcord had been transcribed. Suth would read this before passing it to his son. Carnelian would check the glyphs, then return the parchment to his father. It would be rolled out over the table at his father's feet where Nephron's seal would be appended. The seal of Carnelian's own blood-ring would be added next and the document taken by the sixth ammonite for the perusal of the Masters. The negotiation complete, they would exchange formulaic greetings and the Lords would leave and allow the next party to replace them.

The negotiations became ever more intense as the rank of the Houses fell. In the case of a stipulated number of children, the Imperial Power ceded its rights to choose from the flesh tithe first or gave the child freely without exchange. Portions of the imperial revenue from the cities were assigned to the petitioning Houses for fixed periods of years, or a House would gamble, receiving it only for the duration of the next reign. Eyes were covenanted, the iron coins that were equivalent to ichorous blood. Suth confided in Carnelian that they did not have the time to make the complex arrangements in which the House of the Masks ceded rights to a House on the condition that that House should in turn cede rights to other Houses. The sky was already darkening when they began to barter imperial blood. Brides both living and yet to be born were promised from the imperial forbidden house. In some cases the marriage was restricted to a fixed period, in others it would remain in force until a child was produced.

Carnelian had hardly the strength to hold his head up when his father whispered that the doors were closed until the morrow. He managed to rise, and, with care, manoeuvred his father to his chambers.

'It was good,' his father croaked. 'We have built much today. Tomorrow we will try to finish it.'

They parted and Carnelian dragged himself back to his chamber. Tain brought him some food and put him to bed. His brother said nothing and Carnelian had no energy to find words himself.

The following morning, election's eve, Carnelian came into the Sun in Splendour to find his father with Aurum. He watched them for a while. They were alone, speaking with their hands, the slopes of their robes gleaming only on the side that faced the single brazier. Carnelian was reminded of that time long ago on the baran when he had seen them talking about Ykoriana. As he walked towards them, they turned.

'My Lord Carnelian,' said Aurum, inclining his crowned head. The old Master regarded him for a while, making him feel uncomfortable. 'It seems that I am in your debt, my Lord,' he said grudgingly.

'It is nothing, Lord Aurum.'

Aurum smiled coldly. 'A nothing on which the future of both our Houses depends.'

Suth distracted them with his hand. He looked at his son. The Ruling Lord has come to tell me that there are rumours of more defections.'

'Among the subsidiary lineages?' Carnelian asked.

'Ykoriana builds upon the betrayer within your own House,' said Aurum. There was a tone of accusation in his voice.

'My son and I expected this,' said Suth. 'I think this strategy she has chosen could very well be her undoing.' Aurum rose as he straightened his ranga. 'I will see what I can do.' He bowed to each of them in turn. 'My Lords.' He turned and began the journey to the doors.

I dislike being allied to that Lord, Carnelian signed with his hand.

No more than do I, his father replied. But a chameleon will show wisdom by making common cause with a raven when both are being harried by an eagle.

Carnelian nodded and took his place at his father's right hand. Suth lifted and let fall one of his court staves and immediately the hole opened up in the floor before his dais and began to disgorge its ammonites. Before it closed again, Carnelian saw a flicker of light coming up. It reminded him. He looked over to where, concealed by pillars, the trapdoor lay that led down into the ancient halls, the library and Osidian.

The day progressed very much as had the previous one. Later on, Ruling Lords arrived who admitted that they had agreed to vote for Molochite but were uneasy about the promises Ykoriana was making to the lower lineages. Their own third lineage made an appearance. As they offered him their loyalty, Suth remained aloof and only said that they had taken their time. Still, their votes added some more beads to the tally cord.

The agreements passed through Carnelian's hands in a constant waft of parchment. In every case he endeavoured to make sure that the glyphs had caught the words his father spoke. He grew weary, then exhausted, until the glyphs began to swim before his eyes. Still they went on and he marvelled at the reserves of strength the drugs gave his father. Night fell and still they carried on. More and more his father was husbanding his words. When he spoke, it was with visible effort.

The moon had risen before the flood of Masters became a stream and then a trickle. Then there was a heavy pattern of gongings on the door. 'Is that it?' Carnelian asked.

His father let out a long, long sigh. 'Yes. I must rest… a while.' Carnelian watched his father sag and waited, glad beyond measure that the election was almost upon them. Win or lose, he wanted to take his father home.

Suth roused himself and turned a little to catch Carnelian in his eye. 'Mask yourself.' Carnelian did so and watched with what painful care his father lifted his own mask to his face before he said, 'Ammonites, see again.'

Before him and at his side, all the ammonites removed their masks. Their faces were like parchment written all over with numbers. More appeared out from the hole before the dais. His father sent one off to fetch Ichorians. Carnelian watched the others follow their fellow's movements with fearful eyes. One brought the beadcord of the agreements wound onto a reel and placed it at his father's feet, while another put a length of beadcord in his hands. Carnelian could see with what violence the man's hand trembled and became alarmed. Fanciful thoughts scrambled through his mind, of murderous plots against his father. He rose on his ranga and stood, indecisive. His father could clearly see their fear, they were just in front of him, and yet he made no reaction.

His father only looked up when he heard the footfalls. The ammonite came stumbling back leading a file of Ichorians. Carnelian watched the ammonites line up in front of his father in obedience to his hand's command. 'You have performed your service well. He-who-goes-before thanks you.'

The ammonites all fell into the prostration.

Suth turned to the Ichorians waiting behind. Take them. Destroy them painlessly.'

'My Lord,' cried Carnelian.

His father's hand jerked up, Silence.

'But…'

They have heard too much. They knew this was their fate. It is done today as it is always done.'

Carnelian watched the Ichorians leading the little men off. Only when they had disappeared did his father drop his mask. He hung it on his robe and then looked down at the beadcord in his hand. Carnelian rose and walked to stand in front of him.

His father looked up. 'I hold in my hand our wall of votes. I almost do not dare to count them.'

'Let me do it, Father.'

His father frowned. 'You would have to know how to read the beads.'

Teach me quickly, Father. It does not look too difficult.'

His father showed him how many votes each bead or combination of beads was worth. Carnelian could think of no way to explain that he knew their meaning well and so he pretended to be taught. When his father was finished, Carnelian took the cord. The beads were large, crude, made for insensitive fingers. He began to pay them through his hands, counting.

He ignored the distraction of the sun door opening. He was aware of the clack of ranga coming nearer.

'He counts our votes, my Lord,' his father said to the visitor.

Carnelian counted on, glancing up to see that it was Aurum. 'Eleven thousand nine hundred and eighty-four,' he announced.

His father's eyes closed. 'It is not enough.'

'I might have missed a few.'

'No matter. It is almost a thousand short.'

'We are closer than I expected,' said Aurum. 'Let us not indulge in despondency; there will be time enough for that if we lose.'

Suth looked at him with narrowed eyes. He snorted. 'If we lose, Aurum?'

'Once they are in the Three Lands, many Lords will shift their votes.'

'By a thousand?'

Aurum made a dismissive gesture. 'In the nave, I put a rumour about that Ykoriana intends to extend the franchise to the Lesser Houses.'

Suth smiled a crooked smile. That should put some unease in the hearts of the noble Great.'

'Does My-Lord-who-goes-before wish to go and tell our Lord Nephron of this count?'

Suth smiled again. 'I am without strength for the journey. Besides, my Lord, I am certain you would wish to tell him the good news yourself.'

Aurum frowned and took his leave of them.

Carnelian waited until he was gone before asking, 'Do you share his hope, Father?'

His father shrugged his hands. 'All that can be done, we have done. The result, only the morrow will reveal.' He groaned as he lifted himself up. 'Come, my son, help your weary father to his chambers.'

THE ELECTION

Love came I was its fool

There was joy There was sorrow

(love eclogue – author unknown)

Carnelian woke in such perfect silence that until he made a sound he feared he might have gone deaf. Even the shutters were still, as if the sky was holding its breath. A lingering memory of the Yden evaporated like dew. He remembered and felt as if a weight were settling on his chest. The day of the sacred election had finally arrived.

His fingers remembered the beads of the vote count. As he rose, he tried to cling to Aurum's optimism. He closed his eyes, trying to imagine what might be within the Chamber of the Three Lands' bronze wall of trees. The Masters would all be there with their wintry eyes, Ykoriana and Molochite, Jaspar and Spinel. He glanced back at the bed recalling a tatter of his dream. He smiled. 'Osidian,' he breathed, wanting to feel the name on his lips. His heart began hammering. Surely, he would be there too. He had to be. All Chosen males of an age to wear blood-rings would vote in a sacred election.

He crouched to wake Tain. He had to shake his brother so long that he was relieved when at last his eyes opened. They snapped closed again as if dazzled by Carnelian's white body. He walked away frowning, wanting his brother back the way he had been.

'Master,' Tain said.

Carnelian looked at him standing there, his eyes looking to the floor. He looked as if he were hanging from strings. 'Please, Tain, would you clean me?' He watched the boy go for the pads and unguents. Today is the day when the Gods will be elected.'

Coming towards him, Tain gave a nod. He began cleaning him.

'You know what that means?'

'No, Master.'

That soon the Rains will come and we'll return to our coomb.'

Tain gave another nod.

'Soon things'll return to the way they were, you'll see. Ebeny'll be here, Keal and Brin and Grane and…' Carnelian stopped, unable to put Crail into the list. He went on. They'll all come up from the sea and we'll make a new Hold here.'

Tain gave a nod. Carnelian looked at him. Cold clutched his stomach. What if all of them were like this when they arrived? Carnelian went to open the shutters to let in some light. He stared for a moment at the dawn sky. Its colours were a promise of a fresh new day, but they also looked like blood.

He turned his back on the sky. Tain was still there, waiting with his head hanging. Carnelian returned silendy to stand in front of him and comforted himself with the hope that he might see Osidian, even if only from afar. ‘

Carnelian sent Tain to see who was rapping at the door. The boy opened it a crack, then bowed deeply as he shuffled backwards to open the door wide.

'My Lord,' said Carnelian seeing that it was his father plugging up the entrance. He had to stoop to come in and seemed to fill the chamber with his gold and rubied robe. Tain had fallen to his knees. Looking down from his great height, Suth spoke.

'Rise, child.'

Tain rose, head still hanging.

'Come, look at me.' Tain looked up. Carnelian watched his father's mask survey his marumaga son from on high. 'We are glad to have you back with us, Tain.'

Tain mumbled something.

'Now go and prepare people to come and dress your brother.'

Tain slipped out and Suth removed his mask. His face was troubled. He threw a glance to the door.

'I told you he had not come through this unscathed.'

His father nodded. 'You will have time enough to heal his hurts. Now we must give thought to the day ahead.'

Carnelian withstood the intensity of his father's eyes. He had not felt the pressure of that gaze for an age.

'I have sent commands that the Suth Lords of the other lineages are to come here and take you with them into the Three Lands.'

'I thought, my Lord, I would be there at your side.'

'Even if I were not today He-who-goes-before, I would be sundered from you. At elections, Ruling Lords keep with their peers.'

'What makes my Lord think Spinel will obey him in this when he defies him with his vote?'

Carnelian was glad that the wrath that appeared in his father's face was not turned on him. That Lord will one day give me account for that. How he votes is his business, but I am still his Ruling Lord.' The wrath passed from his face like the shadow of a cloud. 'Come here, my son.'

Carnelian took the steps towards him, feeling his nakedness.

Although his father knelt on his ranga, Carnelian's head only reached his chest. His father took it in his hands. Carnelian looked up into his eyes. He did not see their yellow bloodiness but only the fierce love.

'You know, you are my heart.'

Carnelian's tears distorted his father's face. With a groan of effort, his father managed to bend down to kiss Carnelian's forehead. He let go and rose so that Carnelian's eyes were level with his waist. He took some steps back and hid his face with his sun-eyed mask.

Today all our fates shall be decided.' Carnelian could hear the sorrow in his father's voice. 'Perhaps, even now, we shall be victorious.'

'Aurum said-'

His father cut his reassurances from his mouth with a scissoring motion of his hand and left.

When Tain returned he came with others and Carnelian was forced to hide his distress behind a stony face. He could not rid himself of the harrowing conviction that his father had come to say goodbye.

As they put him into his court robe he bit his tongue to stop himself from spraying them with bitter words. He could not bear to look at Tain's remote expression. When they were finished he almost snatched his Great-Rings from their hands and, ordering the door open, he strode through it so fast he almost toppled over.

The Ichorians lifted the portcullises for him. Carnelian walked through into the nave and was suddenly among giants.

'Cousin Carnelian,' said a voice he recognized as Spinel's. Carnelian saw him there with the others, the nine Lords of House Suth with their chameleon-cyphered court robes. Carnelian looked past them to the gleaming Great. Beyond, the nave ran empty to the closed door of the Chamber of the Three Lands.

Carnelian bowed his head. 'My Lords. My father told me you would be here.'

Then you have spoken to him today, cousin?' asked one of the Lords.

'I have…' Carnelian read the name glyph on his crowns, 'Cousin Veridian.'

The Lord bowed. 'At the service of your lineage, cousin.'

'I am heartened to receive it,' Carnelian said.

'Does our Ruling Lord anticipate victory for his party?'

Carnelian shrugged his hands. 'It hangs in the balance and why should it not when even those of his own House betray him?' He looked at Spinel.

The Lord lifted his right hand to show his blood-ring. This is no mere bauble, my Lord. I will cast its votes as I will. That is my right.'

'And you feel no duty whatever to your Ruling Lord?'

Spinel opened his arms to take in the gleaming concourse. 'Only when we vote does the tyranny of our Ruling Lords lift enough to let us for a moment into the light. Like many others here, I will not be persuaded to walk back into the shadows merely by some rhetoric about family loyalty. Are you making me an offer for my votes, cousin?'

Carnelian controlled his anger, tried to think of something. 'My father is a fair man.' He turned to the other Suth Lords. 'He will treat you as you treat him.'

'I see,' said Spinel. 'So on the basis that your father is a "fair man" you would have me declare myself apostate before all the gathered Great and make the new Gods and Their mother my foes.' He shook his crowned head. 'I think not. I shall honour the agreement I have made with Molochite and we shall see what transpires.'

A Ruling Lord appeared towering at the edge of their group. Carnelian saw the House Imago dragonflies on his robe.

'Internecine conflict within the House Suth, tsk, tsk,' said Jaspar. 'Not that one can own to much surprise, to judge from the lack of care with which its Ruling Lord is wont to treat its interests.'

'My father's interests are his own, Jaspar.'

Looking at Jaspar, Spinel pointed at Carnelian. 'Lord Imago, my kinsman here was attempting to detach me from my agreements.'

'Indeed. That would be foolish, Suth Spinel. One should not lightly abandon one's commitments.'

'Spare us your threats, my Lord,' said Carnelian. 'My kinsman is already determined in his act of treachery. He had better only hope that when this election is over, Ykoriana will be able to protect him from my father's wrath.'

'Carnelian, you should not concern yourself overmuch with that. Once Molochite wears the Masks he will reward his friends and, no doubt, become an inconvenience to those whose lack of foresight led them to become his enemies.'

'We are not afraid-'

Carnelian was interrupted by a chime that shook the air all the way from the Chamber of the Three Lands.

'Aaah, cousin dear, we must discuss your fears some other time. You are summoned into the chamber.'

Another chime rang out. Carnelian waited for its reverberations to dull. 'In spite of all your treacheries, Jaspar, the victory will be ours.'

Jaspar laughed at him through his mask and walked off, dragging a train like a sunset sky.

Carnelian stood rigid, feeling set about with enemies as the bell's pealing shuddered over him. He felt a pulling at his sleeve. He looked up to see his own mask reflected in that of one of the third lineage Lords.

'Come, cousin, we must obey the call of the Turtle's Voice.'

Leading the Suth Lords, Carnelian made his way along the nave as the pealing gusted like a gale. The nave was filling with the processions of the Great like an armada of sails. The bronze trees of the chamber wall rose menacingly ahead. The moat caught their sinister reflection. The Great did not sail across the bridge, for the north-eastern gate was shut. They tacked round towards the south-east, making the gloomy journey to where Carnelian eventually could see the eastern doors were opening like sluice gates, releasing a flickering flood of light. The jewelled oblongs of the Great began bunching as they crossed the bridge accompanied by a shadowy reflected host moving in the moat's black depths. As they passed into the doorway they smouldered and then caught fire.

Carnelian slowed with the others, feeling the dazzle falling on him. A chime hit him with its wave. He began crossing the bridge and saw before him the interior of the chamber filled with a ring of the Lesser Chosen like a lake from which there rose an island fenced about with lantern posts. A wall feathered with fire hedged the Lesser Chosen in. Its whole flickering circuit was breached only where he saw a door open in the north and by the eastern door through which he was entering. Naphtha dragon odour wafted in the swell of the pealing bell.

He looked for the source of all that sound. A mound rose on the low island lying in the midst of the Lesser Chosen. Above this something floated like a summer moon. As he walked towards it down the avenue between the throng, he saw a hammer wielded by syblings hit this moon. It gave out a ripple of sound as if at that moment it had fallen from the sky into the sea. As the vibration rolled over him he faltered and, re-establishing the rhythm of his steps, he became aware of the void above his head. The chamber was open to the night sky. Looking upwards, his eyes could find nothing to see. Fathomless darkness, a dead sky unpricked with stars. He felt its emptiness pouring into his mind through the holes of his eyes and, dropping his gaze, he reminded himself how deep inside the Pillar's rock he was.

He was glad to reach the island's blood-red stone. He had disliked seeing himself twisted in the metal faces of the Lesser Chosen. Steps climbed between the lantern posts, which were tall and slender and grew six branches, each holding aloft a light. He saw the resemblance they bore to the watch-towers he had seen on the road and as he climbed past them he had a notion. The island he had come up onto was a perfect red circle inlaid with a network of silver lines. This was the Guarded Land with its roads. The lantern posts were set around its edge in the positions of the Ringwall cities. The floor of jade and malachite the Lesser Chosen were thronging represented with its greens the encircling lands of the barbarians. The platform that rose at the centre of the chamber seemingly of black glass was fenced by posts carrying the horned-ring of divinity. That was surely Osrakum with its Sacred Wall. The carved stone bell that hung above it in the black air was the Turtle's Voice, and, like the Pillar of Heaven, a connection between earth and sky. The chamber was a wheelmap made stone, the Commonwealth become geometry, the Three Lands captured within a ring of fire.