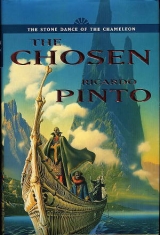

Текст книги "The Chosen"

Автор книги: Ricardo Pinto

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 20 (всего у книги 38 страниц)

Carnelian's eyes settled back to the mirrors of the Yden and the strip of earth that moored it to the cliff upon which he stood. There along that causeway a fleck of light caught in his eye. It glinted again like a signal. He lifted his hand out as if he would pluck it from the distance.

The Grand Sapient's chariot,' said Jaspar even as Carnelian had guessed what it was.

'My father…'

'With Aurum fretting,' said Jaspar and Carnelian could hear the smile in his voice. 'And our dear Lord Vennel.' He chuckled. 'One does not envy him the meeting with his mistress.'

Thoughts of his father brought back Carnelian's headache. He waited for each tiny flicker as if he could read some message in it. He narrowed his eyes to examine the causeway. It looked like nothing much except that it was a road across the Skymere, a lake deeper than the sky. Mountains had been crumbled and fed into that lake so that chariots could roll their wheels across its water. 'Sartlar numberless as leaves…'

'My Lord?' said Jaspar.

Carnelian looked at him. 'Something my father once told me about the building of that road.'

Jaspar looked off towards the causeway. 'It is said that its stones were mortared with sartlar blood.'

Then it is another of their tombs.'

'Hardly, cousin. The Law insists their carcasses be removed from Osrakum. It is true that when we need labour we bring them in from the outer world. But then, those that do not die in the work are slain. The Law forbids that they should return alive from paradise. But be assured, my Lord, that what is left of them is returned. This holy land must not be polluted by the impious dead.'

Carnelian's wonder was souring. He had looked altogether too often on death's black face. The boat was nearing the quay below and so he left the shadow of the turtle and went down to meet her.

The ferryman's robe confused his eyes. Whether it was a white pattern on a black ground or a black pattern on a white, Carnelian could not tell. He stared at the man's ivory mask, the face of a dead Master locked into a right profile. Half a face with a single eye staring out of it. It was like those ill-omened faces in the glyphs that encoded sinister words. Carnelian stopped his head turning in unconscious mimicry. The ferryman wore a crown in which the turtleshell sky glyph was the body of a nest of bony limbs that could have been the remains of a crab bleaching on a shore.

The pattern on the ferryman's robe moved, entangling Carnelian's eyes so that it took him a while to notice the outstretched whitewashed hand. Carnelian looked at it, not knowing what to do.

'The kharon asks for his fee,' said Jaspar.

Carnelian watched the Master pull off a ring that he dropped onto the ferryman's hand. The man did not close his hand but brought it back to Carnelian who looked at his own hands. All he had was his rusty blood-ring. He turned to Jaspar. 'Can my Lord lend me some gold?'

The kharon take only jade.' Jaspar twisted another ring from his finger and handed it to Carnelian, who took it and made to give it to the ferryman.

The other hand, my Lord, the other hand.'

Carnelian did not understand what he meant.

'If the jade is given with the left hand the kharon will only take you across to the Isle. Put the jade in your right hand.'

Carnelian did as he was told. The ferryman's whitened hand closed around the rings as he moved back from the bow. Jaspar reached out to clasp one of the posts rising from the gunnel and pulled himself aboard. Other than Jaspar and the ferryman there was no-one the length of the deck. The whole boat was yellow-white, patched together from rods and roundels. An ivory boat. Carnelian reached out to grasp the post. Its knobbed shaft slipped smoothly into his hand. Its carving was picked out in brown. He realized what it was. Quickly, he heaved himself onto the deck and let go of it in disgust.

'Is anything the matter, cousin?' said Jaspar.

Carnelian stared at the cobbled deck that narrowed up at either end to posts as pale and slender as beech saplings.

'Come, sit here, cousin.' Jaspar rested his hand on the back of a chair. There were three of them under a dark canopy.

Carnelian walked across the cobbles as carefully as if they had been eggshells. 'Bones… there are bones everywhere.'

'Of course,' said Jaspar. This is a bone boat.'

Carnelian looked round, aghast. 'But human bones…?'

'Sit down, cousin.'

Carnelian walked round and sat in a chair beside Jaspar. He craned his neck round. The ferryman was there, his ivory face looking as if it were a carved part of the stern post. He held the handle of a steering oar in each hand. The boat began to turn away from the quay. Soundlessly the oar heads spooned the water on either side.

'I thought it a fairytale.'

Jaspar chuckled. He tapped the arms of the chair. 'If you look under your arm, cousin, you will see that even these chairs are made of bones.'

Carnelian lifted his arms, saw the chair was a mosaic of finger bones. Here and there was the tell-tale green pinprick of a copper rivet.

This deck,' Jaspar was tapping his foot, 'skulls.'

Carnelian could see how the cobbles were of ovals of different sizes, fissured brown. He gave up trying to estimate how many had been used to make the deck. 'Generations…'

'Since the Twins raised up the Sacred Wall,' said Jaspar. 'Our dear ferryman,' he glanced back at the stern, 'and all his brethren rowing beneath our feet, will one day add their own bones to this very vessel. These boats are the tombs of their race.'

Tombs,' muttered Carnelian. His head ached. He rested it against the back of the chair and closed his eyes. Tombs. And what of his House tomb? He imagined consigning his father to its everlasting night.

He opened his eyes. Beyond the sapphire water the Yden spread its meres as a floor of varied jades. Something winked on the thread of road that ran along its stony margin. At that signal the crystal air shattered as flamingos rose in a red blizzard. Carnelian watched for the sparking on the road that showed where the silver chariot was making its progress beneath their cloud. He closed his eyes to trap their tears and choked down the voice that was telling him he would never see his father again.

Carnelian longed to kite away on the breeze but his heart weighed him down. Its beating echoed up into his head. His face inflated into the sweaty shell of his mask.

'Behold your coomb, my Lord,' said Jaspar.

Carnelian looked up blearily. Crags. He pushed his head back, and further back, until at last he had to narrow his eyes against the sky glare as he reached the jagged edge of the Sacred Wall. He dropped his eyes, dizzied, appalled by the scale of it.

'You really will have to do something about your palaces, cousin.'

Carnelian gaped at him. 'Do something?'

The Master waved his hand, shook his head. 'It is all so old-fashioned.' He indicated some scaffolding. There something is being done, but not enough, not nearly enough. The overall lack of decoration positively reeks of past times. Where are the pierced roof combs, the tortured friezes? Look at those meagre columns. They are like starved girls and those domes are as flat as their breasts. But I forget, cousin, you have been so long away and can have little notion of what canons are fashionable among the Great.'

Carnelian turned back to gaze at the lean, elegant symmetries.

'Especially when you are possessed of so much space,' Jaspar added, with a twinge of envy.

Carnelian saw that they were moving towards a quay set to one side of the coomb. There was a rustle beside him. Jaspar was adjusting his robe. Carnelian's ears still rang with his patronizing tones and now the Master was readying himself to disembark. Carnelian peered back at the coomb. Those facades concealed other Masters of his House. His guts told him that this was not his home. That was lost, far away, in a different fairytale.

'I might as well accompany you, cousin,' drawled Jaspar.

There is no need.'

'Aaah, but, Carnelian, you forget that one is still striving to earn the gratitude of House Aurum.'

'It will be difficult enough… I know nothing of my kin.' Carnelian clutched the air for words. This new world…' He was feeling so many emotions. He stood up, walked to the bow rail, blinked until he could see again. The bay swelled up into the middle of the coomb where the water extended its colours up into a pebbled beach. He went towards the stern, aware of the cobbling in the skull deck, steadying himself on the rail. The ferryman was a sinister doll. The only living part of him were the hands that stroked the handles of the steering oars.

'I would have you leave me on the beach,' Carnelian said to the ivory mask, seeking the brightness of an eye behind its single slit. He clenched his fists. Did the creature even have ears? He was lifting his hand to point when he saw the ferryman's fingers urge the steering oars to the right and he felt the boat veer to port. Turning, he saw that her prow was pointing into the bay.

He walked back to where Jaspar stood waiting, his hands on his hips. 'Why have we changed course, my Lord?'

Carnelian's hands made warding motions that he could see Jaspar tried to read, then he was past him and Jaspar's protests became nothing more than seagull cries. Carnelian reached the prow post, embraced its elaborate fluting of thighbones. The crescent of the beach was rushing towards him, the water turquoising as it shallowed. The boat slowed. He could see that if she were to go much further she would run aground. He turned to look back. Jaspar was closing in on him, hiding everything behind his vast shape. Suddenly, Carnelian could not bear to have a Master near him. He swung himself round the prow post, let go and fell like an anchor. The water sucking up to receive him squeezed out a gasp. He found his feet and fought his way towards the shore against the drag of his robe. When the water was around his knees he swung round panting and saw the boat already turning, showing her bony length and the gradient of her oars. Carnelian glimpsed Jaspar who had a flash for a face, then the boat had swung about to hide him with her stern and was sliding away, stirring the wake with her shoulder-blade steering oars.

Carnelian heaved his robe out of the water and crunched up the pebble beach. One last tug caused him to stumble. He fell onto his hands, cursing. He pulled against the weight of soaked cloth and sat up. His palms felt contours in the pebbles. He picked one up that was as blue as the Skymere. A fish twisted round on itself in the lapis lazuli. Its tiny scales snagged the end of his finger. Its gills were delicate fans. He put it down carefully and picked up another pebble. A piece of flawed jade, carved into a fern spiral. He looked round him. All the pebbles were carved. He stared along the sweep of the beach, his hand stroking the spiralled jade. So many pebbles. He tried to imagine the labour they represented, but he might as well attempt to count the stars in a night sky.

A movement caught his eye. He straightened to see a man up the beach, frozen. As Carnelian clambered to his feet, the man yelped and fled. Carnelian attempted to run after him but his feet scooped pebbles as his robe held him back like chains. He gave up and watched the man lope up some steps and disappear into trees.

'Let them find me,' he muttered. He tucked the jade pebble into a pocket and stooped to remove his shoes. He gathered up his robe and wrung some of the water out of it. His feet looked very white. He worried that the water might have washed off their paint. He shrugged. What could he do if it had? He hoisted the train of his robe over one arm and sauntered up the beach feeling the pebbles' carvings with his toes. Something was whirring in the air. He turned his head slowly. A dragonfly was hovering in the blur of its wings, the size of a dagger but more exquisitely enamelled.

Voices across the beach wafted it away. A familiar clink of armour made him turn. Perhaps a dozen guardsmen were filing towards him. Carnelian almost cried out when he saw their chameleon tattoos. He dropped his robe to wait for them. They looked at him uncertainly, rounding their shoulders. He searched their faces, then cursed his stupidity at trying to find one he knew. Their commander plunged his knees into the pebbles and in threes and fours the others followed him.

Carnelian did not know what to say.

'Master, please take no offence,' the commander said without lifting his eyes, 'but our Masters've given us no warning of your visit. If you'd please go, Master, go' – he pointed – 'back to the quay and wait with your tyadra, someone appropriate'll come down to greet you… Master.'

Carnelian shook his head. There's no tyadra.' He lifted his arms from his sides. 'I'm here as you see me.'

'Of course it's not my place, but… the Master shouldn't be here.'

'Don't worry, I'm not trespassing… what's your name?'

The man looked up fearfully. 'M-Moal, if it please you, Master.'

'Well, Moal, I'm your Master's son returned.'

Others were sneaking looks at him. Moal chewed his lip. 'Our Master's son's well known to us.'

Carnelian had to think about that for a moment. 'No, not the Master you have here. I meant the Master of this House, who's long been away.'

Several of the guardsmen forgot themselves enough to stare, but quickly ducked their heads. Carnelian watched their hands fussing with their weapons.

'Is there someone I can talk to?'

'If it pleases you, Master, someone'll be here soon,' mumbled Moal.

So Carnelian waited, eventually turning his back on them because he did not want to see their grovelling. He reached down to squeeze more water out of his robe, all the time feeling their stares.

'Master?'

A woman's voice. He turned and instantly a weight of tears stiffened his face. It was Brin. He squeezed his eyes closed several times. He gritted his teeth. She was still there. His shoulders sagged; it was not Brin. This woman was younger, though she was very like his aunt.

The woman bowed. 'Master, why are you come to Coomb Suth?'

Carnelian squared his shoulders. 'It's my coomb. I'm Suth Carnelian.' The colour left her face where Carnelian saw his father's eyes. 'You're… Fey.'

The woman flinched, nodded. 'Yes, Master, steward of this House, Master. Please… I don't understand. Forgive my confusion, Master, please…'

Carnelian gazed at those eyes. It was almost as if this woman had stolen them from his father. He paused a moment, thinking, and then reached back to release his mask.

Fey threw her hands up in horror. 'Master, would you blind us all?'

'But we're all of one House… I'm Suth Carnelian.' He realized that the woman might find his face no proof at all. Suddenly he made a fist and cried, 'Look.' He thrust out his hand so that the woman could see the Ruling Ring on his hand.

Fey leaned forward, choked a cry and crumpled into the pebbles. 'Master,' she said from Carnelian's feet, 'oh, Master.'

Carnelian crouched down and putting his hands round Fey's shoulders lifted her gently. It was only then he saw the tears striping her face.

'Are you so happy, Fey?'

'Of course happy, Master, but also I grieve for our Master, your father.'

Carnelian shook the woman. 'When did the news come? When did it come?'

'News… news?' spluttered Fey. The ring, Master, the ring.'

Carnelian let her go. He looked at the Ruling Ring on his finger. Would that finger soon be its proper place? He held his head at his stupidity. There had been no time for any news. 'I'm a fool,' he said aloud.

Fey was dabbing tears from her eyes. The guardsmen looked miserable. These strangers were also his people. He was forgetting his duty to them.

'I'm sorry, Fey. You misunderstood me.' He removed the Ruling Ring. 'I don't have the right to wear it. It's a long story. My father was ill when I parted from him in the Valley of the Gate. The Wise'll heal him and then we'll have him back here with us.'

His confidence visibly cheered the guardsmen. Fey looked uncertain.

'I hope I didn't hurt you? When I shook you? I forgot myself…'

Fey stared.

Carnelian put his hands up to his mask. 'Now, if you don't mind, I'd like to remove this thing.' 'Master, your will's our will.'

Carnelian removed the mask, rubbed at the grooves in his skin, smiling at Fey, allowing her to search his face. 'You see my father?'

Fey looked hard at him then nodded unconvincingly, giving a thin smile. 'Yes, Master.'

'I'd rather you cut that out, Fey. My name's Carnelian.'

Fey frowned, shook her head. 'It's forbidden me to soil a Master's name with my tongue.'

It was Carnelian's turn to frown. The thought of his next question made him grimmer still.

Fey spoke first. 'My Master, your robe's wet.'

'Never mind that. Where're the other Masters, my kin?'

'In the Eyries, Master.' Carnelian must have looked uncertain because Fey turned to point up the Sacred Wall.

Carnelian scanned the craggy heights. It took him a while before he saw what looked like scratches halfway up to the sky.

'More than fifty days ago our Masters went up there to avoid this heat. I'll make immediate preparations for you to join them, Master.'

Carnelian was still looking up. 'Perhaps tomorrow, Fey. Tonight I'd like to stay down here.'

Fey looked aghast. That's impossible, Master.'

'Why?'

These halls have become unsuitable for a Master. Workmen're everywhere… the Master must understand that we always carry out restoration work when the Masters go up to the Eyries… furniture's been stored away… Master, there's no accommodation suiting of your rank.'

'You'll find me easy to please, Fey.' He silenced any more of her protests with his hand and eventually, accepting that she was not going to change this strange young Master's mind, Fey led him off into the palace with the escort of the guardsmen, some of whom carried his soaking train.

Carnelian and the escort were a thread pulled by Fey's needle. There was a hall that was like a wood, its sultry air nuanced with odours. The day was only a glowing band in the distance. He felt more than saw the eyes in the mosaics. Murals had the colours of concealed jewels. Wisps of voices ribboned between the columns. A door closing seemed an echo still lingering from the day before. Floors rainbowed like oil on water. Sometimes he glimpsed courts whose colours were more vibrant than any dream. Awe infected him like a fever so that, when he saw the eye and dancing chameleon ward on the lintels of a door, he sighed his relief that they were leaving the echoing grandeur of the public chambers.

At Carnelian's request, they left the guardsmen behind. Against Fey's protests, Carnelian insisted on carrying his wet train in the crook of his arm. Steps took them down into a courtyard carpeted with the petals that were drizzling down from the trees. They kicked their way through the drifts, walking round the urns that held the trees. At the edge of the courtyard there rose a gate of white wood warded with eyes.

As they walked away from the gate Carnelian reached out to touch Fey's shoulder. The halls of a subsidiary lineage?'

The woman blushed. The halls of the first lineage.' 'But then why …?'

Fey bowed her head. They've long been occupied by the secondary lineage. There've been changes, Master.'

Carnelian looked up at the white doors. 'Have there?' he said, and not wanting to make trouble for her, he allowed her to lead him away.

Several more gates and courtyards brought them to a door in a wall. Fey pushed against it and Carnelian leaned over her to help. They walked into a small courtyard around which ran raised porticoes. Water slid round its edge in a shallow channel. In one place its lip had crumbled and water oozed down, greening the marble, running into a puddle. Some dull bronze troughs held dry, brown-leafed trees whose parched earth had pulled away from the sides. Dust greyed the precious inlay walls.

This quarter hasn't been used in a while,' said Carnelian, trying to hide his disappointment. He would not let Fey kneel.

Fey grimaced as she looked round her. These were some of the halls of the third lineage, Master. They now occupy the quarter traditionally belonging to the second, who-'

'Who now occupy my father's halls,' said Carnelian heavily.

Fey cringed a little, as if she were expecting a blow.

'As you said, Fey, there've been changes.'

Fey went over to one of the withered trees, touched its plug of soil, shook her head. This shouldn't have been allowed.' She looked back at Carnelian. 'You must believe that I did everything I could, Master.'

Carnelian walked up to Fey and put his arm round her shoulders. The woman went so stiff that Carnelian immediately pulled his arm away. 'I do believe you. Now come on, show me where I can wash away this paint.'

They walked together round several more courtyards till they came to an echoing suite of chambers whose lofty vermilion walls were mosaiced with slender waving lilies and soaring birds.

'For one night, perhaps, these chambers'll be adequate for the Master,' said Fey, opening tall blue rectangles of sky in a faraway wall.

Narrowing his eyes against the glare, Carnelian crossed the marble mirror floor. He stood beside Fey in the flooding sunlight. Below, a pebbled cove smeared its green into the azure of the Skymere. Further off was the fiery emerald vision of the Yden and the Pillar of Heaven towering up from its heart. Carnelian closed his eyes and drew in the perfume of Osrakum. 'Miraculous,' he sighed.

When he opened his eyes Fey was smiling at him. 'You are like your father, Master.'

Carnelian felt a twinge of guilt as he looked at the barrow of the Labyrinth mounding up from the Yden. How could he feel joy when his father might be there, somewhere, dead?

Fey saw his frown. To wash you'll need slaves, Master. I'll send them to attend you, and to clean up this mess. If the Master'd allow me to guide him…' She waited to see him move, then bustled out through another door.

Carnelian followed her on a long walk to a chamber of yellow marble. One whole wall was so thin that it glowed as it filtered daylight.

'It's like being inside a sea shell,' Carnelian said in delight.

Fey walked to the door. 'I'll go and fetch body slaves.' Carnelian touched her arm. 'I'd rather be alone.' Fey looked startled. 'But who'll wash you, Master?' The Master'll wash himself.'

Fey's eyebrows lifted and creased her brow. 'As the Master wishes, so shall it be done.'

As Carnelian slipped the damp robe off, something cracked to the floor. Crouching, he picked it up. It was the jade pebble. He frowned when he saw that its spiral had cracked in two. He put the pieces inside the hollow of his mask and put that face down on the robe. He went to the water wall and fiddled with the golden sluices set into its channels. At last he managed to braid the water into a single splashing waterfall. He gasped as he slid into its envelope, tensing in the cold. It roared over his head. The paint leached away down his legs. The water pooling round his feet was like milk, but soon ran clear.